Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome

| Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome, Four Corners disease, hantavirus disease | |

| |

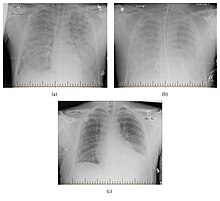

| Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome on chest X-ray | |

| Specialty | Respirology |

| Symptoms | Early: Tiredness, fever, muscle pains[1] Later: Cough, shortness of breath, chest tightness[1] |

| Usual onset | 1 to 8 weeks after exposure[1] |

| Causes | Certain hantaviruses spread by rodents[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Evidence of hantavirus together with ARDS[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Pneumonia, influenza, tularemia, salicylate toxicity, Dengue[3] |

| Prevention | Rodent control[4] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[5] |

| Frequency | Less than 50 cases a year (USA)[6] |

| Deaths | 38% mortality[1] |

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) is a types of hantavirus infection.[2] Early symptoms may include tiredness, fever, and muscle pain.[1] Other symptoms may include headache, vomiting, and diarrhea.[1] About a week after onset, cough, shortness of breath, and chest tightness may occur.[1] Onset of initial symptoms is generally 1 to 8 weeks following exposure.[1]

A number of types of orthohantavirus may result in the disease including Sin Nombre hantavirus carried by deer mice, and New York hantavirus carried by white-footed mice.[7] The disease is typically spread when people breath in air contaminated by rodent droppings.[7] It generally does not spread between people.[7] Diagnosis involved detecting hantavirus RNA, immunoglobulins, or antigens together with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[2]

Prevention is by avoiding rodents.[4] There is no specific treatment.[5] Supportive care improves outcomes and may include oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation.[5] About 38% of those who are infected die as a result.[1] Those who recover, generally do so completely.[5]

The disease occurs in North and South America.[7] It is more common in rural areas.[7] Between 1993 and 2018, 11 to 48 cases were diagnosed a year in the United States.[6] The states most commonly affected are Colorado and New Mexico.[8] The condition was first identified in 1993.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Initially, HPS has a incubation phase of 2–4 weeks, in which patients remain asymptomatic.[9] Subsequently, people can experience 3–5 days of flu-like prodromal phase symptoms, including fever, cough, muscle pain, headache, lethargy, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.[9]

Cause

A number of types of orthohantavirus may result in the disease including Black Creek Canal virus (BCCV), New York orthohantavirus (NYV), Monongahela virus (MGLV), Sin Nombre orthohantavirus (SNV), and certain other members of hantavirus genera that are native to North America.[10] Specific rodents are the principal hosts of the hantaviruses including the hispid cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) in southern Florida, which is the principal host of Black Creek Canal virus.[11][12] The deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) in Canada and the Western United States is the principal host of Sin Nombre virus.[13][14] The white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) in the eastern United States is the principal host of New York virus.[15] In South America, the long-tailed mouse (Oligoryzomys longicaudatus) and other species of the genus Oligoryzomys have been documented as the reservoir for Andes virus.[16][17][18]

Transmission

The virus can be transmitted to humans by a direct bite or inhalation of aerosolized virus, shed from stool, urine, or saliva from a natural reservoir rodent.[9] In general, droplet and/or fomite transfer has not been shown in the hantaviruses in either the pulmonary or hemorrhagic forms.[19][20]

Mechanism

In the following 5–7 day cardiopulmonary phase, the patient's condition rapidly deteriorates into acute respiratory failure, characterized by the sudden onset of shortness of breath with rapidly evolving pulmonary edema, as well as cardiac failure, with hypotension, tachycardia and shock.[9] In this phase, patients may develop acute respiratory distress syndrome. It is often fatal despite mechanical ventilation and intervention with diuretics. After the cardiopulmonary phase, patients can enter a diuretic phase of 2–3 days characterized by symptom improvement and diuresis. Subsequent convalescence can last months to years.[9]

Diagnosis

The preferred method for diagnosis is serological testing which identifies both acute (IgM) and remote infections (IgG), however PCR may also be used to identify early infections.[21]

Prevention

Rodent control in and around the home or dwellings remains the primary prevention strategy, as well as eliminating contact with rodents in the workplace and at campsites. Closed storage sheds and cabins are often ideal sites for rodent infestations. Airing out of such spaces prior to use is recommended. People are advised to avoid direct contact with rodent droppings and wear a mask while cleaning such areas to avoid inhalation of aerosolized rodent secretions.[22]

Treatment

There is no cure or vaccine for HPS. Treatment involves supportive therapy, including mechanical ventilation with supplemental oxygen during the critical respiratory-failure stage of the illness.[9] Although ribavirin can be used to treat hantavirus infections, it is not recommended as a treatment for HPS due to unclear efficacy and likelihood of medication side effects.[9]

Epidemiology

HPS appears to occur specifically in North and South America, although other Hantavirus infections also occur in Eastern Asia and Latin America.[23]

HPS does not occur in any specific racial group of people.[23]

Outcome

HPS ranges from mild to severe disease, and the outcome varies with the severity of disease. Up to 50% may be fatal.[23] Mild cases usually have a good outcome with full recovery. Most people who recover from severe disease usually do so over a long period of time but without impaired heart or lung function.[23]

History

HPS was first thought to have occurred during the 1993 outbreak in Four Corners region of the southwestern United States, and was identified by Bruce Tempest.[24] Initially named "Four Corners disease", the term was changed to Sin Nombre virus after complaints by Native Americans that the name "Four Corners" stigmatized the region.[24] Laboratory techniques later revealed that the disease had occurred prior to 1993 and that by this method the earliest known case was in 1959 in a 38-year-old man from Utah.[24] It has since been identified throughout the United States.[24]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 "Signs & Symptoms | Hantavirus | DHCPP | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 February 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome | 2015 Case Definition". wwwn.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ Akram, SM; Mangat, R; Huang, B (January 2021). "Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary Syndrome". PMID 29083610.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Prevention | Hantavirus | DHCPP | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 February 2019. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Diagnosis & Treatment | Hantavirus | DHCPP | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 February 2019. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Reported Cases of Hantavirus Disease | Hantavirus | DHCPP | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "Transmission | Hantavirus | DHCPP | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 February 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ "Hantavirus Disease, by State of Reporting | Hantavirus | DHCPP | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 26 February 2019. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Barros, N; McDermott, S; Wong, AK; Turbett, SE (16 April 2020). "Case 12-2020: A 24-Year-Old Man with Fever, Cough, and Dyspnea". New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (16): 1544–1553. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc1916256. PMID 32294350.

- ↑ Nichol ST. Beaty BJ. Elliott RM. Goldbach R, et al. Family Bunyaviridae. In: Fauquet CM, editor; Mayo MA, editor; Maniloff J, editor; Desselberger U, et al., editors. Virus Taxonomy: 8th Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press;

- ↑ Rollin PE. Ksiazek TG. Elliott LH. Ravkov EV, et al. "Isolation of Black Creek Canal virus, a new hantavirus from Sigmodon hispidus in Florida", J Med Virol. 1995;46:35–39. [PubMed]

- ↑ Glass GE. Livingstone W. Mills JN. Hlady WG, et al. "Black Creek Canal virus infection in Sigmodon hispidus in southern Florida", Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:699–703. PubMed

- ↑ Childs JE, Ksiazek TG, Spiropoulou CF, Krebs JW, Morzunov S, Maupin GO, Gage KL, Rollin PE, Sarisky J, Enscore RE (1994). "Serologic and genetic identification of Peromyscus maniculatus as the primary rodent reservoir for a new hantavirus in the southwestern United States". J. Infect. Dis. 169 (6): 1271–80. doi:10.1093/infdis/169.6.1271. PMID 8195603. Archived from the original on 2020-05-26. Retrieved 2019-09-20.

- ↑ Drebot MA. Gavrilovskaya I. Mackow ER. Chen Z, et al. "Genetic and serotypic characterization of Sin Nombre-like viruses in Canadian Peromyscus maniculatus mice", Virus Res. 2001;75:75–86. [PubMed]

- ↑ Hjelle B. Lee SW. Song W. Torrez-Martinez N, et al. "Molecular linkage of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome to the white-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus: genetic characterization of the M genome of New York virus", J Virol. 1995;69:8137–8141. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- ↑ Wells RM, Sosa Estani S, Yadon ZE, Enria D, Padula P, Pini N, Mills JN, Peters CJ, Segura EL (April–June 1997). "An unusual hantavirus outbreak in southern Argentina: person-to-person transmission? Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome Study Group for Patagonia". Emerg Infect Dis. 3 (2): 171–4. doi:10.3201/eid0302.970210. PMC 2627608. PMID 9204298.

- ↑ Levis S, Morzunov SP, Rowe JE, Enria D, Pini N, Calderon G, Sabattini M, St Jeor SC (March 1998). "Genetic diversity and epidemiology of hantaviruses in Argentina". J Infect Dis. 177 (3): 529–38. doi:10.1086/514221. PMID 9498428.

- ↑ Cantoni G, Padula P, Calderón G, Mills J, Herrero E, Sandoval P, Martinez V, Pini N, Larrieu E (October 2001). "Seasonal variation in prevalence of antibody to hantaviruses in rodents from southern Argentina". Trop Med Int Health. 6 (10): 811–6. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00788.x. PMID 11679129.

- ↑ Peters, C.J. (2006). "Emerging Infections: Lessons from the Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers". Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 117: 189–197. PMC 1500910. PMID 18528473.

- ↑ Crowley, J.; Crusberg, T. "Ebola and Marburg Virus Genomic Structure, Comparative and Molecular Biology". Dept. of Biology & Biotechnology, Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Archived from the original on 2013-10-15.

- ↑ Akram, Sami (20 November 2020). "Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary Syndrome". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ "CDC - Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS) – Hantavirus". Cdc.gov. 2013-02-06. Archived from the original on 2013-05-24. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Cennimo, David J . (15 June 2019). "Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". www.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 "CDC - History of Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS) - Hantavirus". www.cdc.gov. 11 March 2020. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

External links

- "Hantaviruses, with emphasis on Four Corners Hantavirus" by Brian Hjelle, M.D., 2001, Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, University of New Mexico

- Hantavirus Technical Information Index page Archived 2012-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, US Center for Disease Control

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Bunyaviridae Archived 2013-01-13 at archive.today

- Hantavirus – Occurrences and deaths in North and South America, 1993–2004 Archived 2012-03-10 at the Wayback Machine, PAHO