Cyanocobalamin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | sye AN oh koe BAL a min[1] |

| Trade names | Cobolin-M,[1] Depo-Cobolin,[1] others[2] |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, intramuscular, nasal spray[3][4] |

| Defined daily dose | 1 mg (by mouth)[5] 70 mcg (nasal)[5] 20 mcg (by injection)[5] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| MedlinePlus | a604029 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Chemical and physical data | |

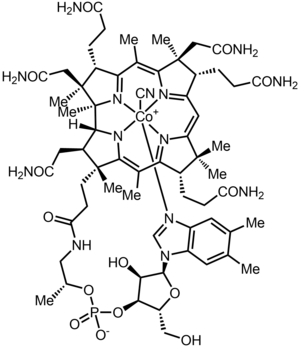

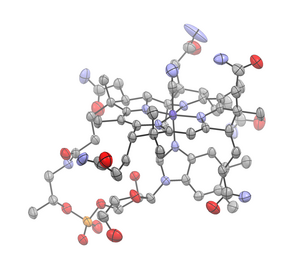

| Formula | C63H88CoN14O14P |

| Molar mass | 1355.388 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 300 °C (572 °F) + |

| Boiling point | 300 °C (572 °F) + |

| Solubility in water | 1/80g/ml |

| |

| |

Cyanocobalamin is a manufactured form of vitamin B

12 used to treat vitamin B12 deficiency.[1] The deficiency may occur in pernicious anemia, following surgical removal of the stomach, with fish tapeworm, or due to bowel cancer.[6] It is less preferred than hydroxocobalamin for treating vitamin B12 deficiency.[3] It is used by mouth, by injection into a muscle, or as a nasal spray.[3][4]

Cyanocobalamin is generally well tolerated.[7] Minor side effects may include diarrhea and itchiness.[8] Serious side effects may include anaphylaxis, low blood potassium, and heart failure.[8] Use is not recommended in those who are allergic to cobalt or have Leber's disease.[6] Vitamin B

12 is an essential nutrient meaning that it cannot be made by the body but is required for life.[9][7]

Cyanocobalamin was first manufactured in the 1940s.[10] It is available as a generic medication and over the counter.[3][7] In the United Kingdom it costs the NHS about £2.90 per injection as of 2019.[3] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount was about US$0.77 in 2019.[11] In 2017, it was the 170th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than three million prescriptions.[12][13]

Medical use

Cyanocobalamin is usually prescribed after surgical removal of part or all of the stomach or intestine to ensure adequate serum levels of vitamin B

12. It is also used to treat pernicious anemia, vitamin B

12 deficiency (due to low intake from food), thyrotoxicosis, hemorrhage, malignancy, liver disease and kidney disease. Cyanocobalamin injections are often prescribed to gastric bypass patients who have had part of their small intestine bypassed, making it difficult for B

12 to be acquired via food or vitamins. Cyanocobalamin is also used to perform the Schilling test to check ability to absorb vitamin B

12.[14]

Cyanocobalamin is also produced in the body (and then excreted via urine) after intravenous hydroxycobalamin is used to treat cyanide poisoning.[15]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 1 mg by mouth, 70 mcg in the nose, and 20 mcg by injection.[5]

Side effects

Possible side effects of cyanocobalamin injection include allergic reactions such as hives, difficult breathing; redness of the face; swelling of the arms, hands, feet, ankles or lower legs; extreme thirst; and diarrhea. Less-serious side effects may include headache, dizziness, leg pain, itching, or rash.[16]

Treatment of megaloblastic anemia with concurrent vitamin B

12 deficiency using B

12 vitamers (including cyanocobalamin), creates the possibility of hypokalemia due to increased erythropoiesis (red blood cell production) and consequent cellular uptake of potassium upon anemia resolution.[17] When treated with cyanocobalamin, patients with Leber's disease may suffer serious optic atrophy, possibly leading to blindness.[18]

Chemistry

Vitamin B

12 is the "generic descriptor" name for any vitamers of vitamin B

12. Animals, including humans, can convert cyanocobalamin to any one of the active vitamin B

12 compounds.[19]

Cyanocobalamin is one of the most widely manufactured vitamers in the vitamin B

12 family (the family of chemicals that function as B

12 when put into the body), because cyanocobalamin is the most[citation needed] air-stable of the B

12 forms. It is the easiest[citation needed] to crystallize and therefore easiest[citation needed] to purify after it is produced by bacterial fermentation. It can be obtained as dark red crystals or as an amorphous red powder. Cyanocobalamin is hygroscopic in the anhydrous form, and sparingly soluble in water (1:80).[citation needed] It is stable to autoclaving for short periods at 121 °C (250 °F). The vitamin B

12 coenzymes are unstable in light. After consumption the cyanide ligand is replaced by other groups (adenosyl, methyl) to produce the biologically active forms. The cyanide is converted to thiocyanate and excreted by the kidney.[citation needed]

Chemical reactions

In the cobalamins, cobalt normally exists in the trivalent state, Co(III). However, under reducing conditions, the cobalt center is reduced to Co(II) or even Co(I), which are usually denoted as B

12r and B

12s, for reduced and super reduced, respectively.

B

12r and B

12s can be prepared from cyanocobalamin by controlled potential reduction, or chemical reduction using sodium borohydride in alkaline solution, zinc in acetic acid, or by the action of thiols. Both B

12r and B

12s are stable indefinitely under oxygen-free conditions. B

12r appears orange-brown in solution, while B

12s appears bluish-green under natural daylight, and purple under artificial light.[20]

B

12s is one of the most nucleophilic species known in aqueous solution.[citation needed] This property allows the convenient preparation of cobalamin analogs with different substituents, via nucleophilic attack on alkyl halides and vinyl halides.[20]

For example, cyanocobalamin can be converted to its analog cobalamins via reduction to B

12s, followed by the addition of the corresponding alkyl halides, acyl halides, alkene or alkyne. Steric hindrance is the major limiting factor in the synthesis of the B

12 coenzyme analogs. For example, no reaction occurs between neopentyl chloride and B

12s, whereas the secondary alkyl halide analogs are too unstable to be isolated.[20] This effect may be due to the strong coordination between benzimidazole and the central cobalt atom, pulling it down into the plane of the corrin ring. The trans effect determines the polarizability of the Co–C bond so formed. However, once the benzimidazole is detached from cobalt by quaternization with methyl iodide, it is replaced by H

2O or hydroxyl ions. Various secondary alkyl halides are then readily attacked by the modified B

12s to give the corresponding stable cobalamin analogs.[21] The products are usually extracted and purified by phenol-methylene chloride extraction or by column chromatography.[20]

Cobalamin analogs prepared by this method include the naturally occurring coenzymes methylcobalamin and cobamamide, and other cobalamins that do not occur naturally, such as vinylcobalamin, carboxymethylcobalamin and cyclohexylcobalamin.[20] This reaction is under review for use as a catalyst for chemical dehalogenation, organic reagent and photosensitized catalyst systems.[22]

Production

Cyanocobalamin is commercially prepared by bacterial fermentation. Fermentation by a variety of microorganisms yields a mixture of methylcobalamin, hydroxocobalamin and adenosylcobalamin. These compounds are converted to cyanocobalamin by addition of potassium cyanide in the presence of sodium nitrite and heat. Since multiple species of Propionibacterium produce no exotoxins or endotoxins and have been granted GRAS status (generally regarded as safe) by the United States Food and Drug Administration, they are the preferred bacterial fermentation organisms for vitamin B

12 production.[23]

Historically, the physiological form was initially thought to be cyanocobalamin. This was because hydroxocobalamin produced by bacteria was changed to cyanocobalamin during purification in activated charcoal columns after separation from the bacterial cultures (because cyanide is naturally present in activated charcoal).[24] Cyanocobalamin is the form in most pharmaceutical preparations because adding cyanide stabilizes the molecule.[25]

The total world production of vitamin B12, by four companies (the French Sanofi-Aventis and three Chinese companies) in 2008 was 35 tonnes.[26]

Metabolism

The two bioactive forms of vitamin B

12 are methylcobalamin in cytosol and adenosylcobalamin in mitochondria. Multivitamins often contain cyanocobalamin, which is presumably converted to bioactive forms in the body. Both methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin are commercially available as supplement pills. The MMACHC gene product catalyzes the decyanation of cyanocobalamin as well as the dealkylation of alkylcobalamins including methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin.[27] This function has also been attributed to cobalamin reductases.[28] The MMACHC gene product and cobalamin reductases enable the interconversion of cyano- and alkylcobalamins.[29]

Cyanocobalamin is added to fortify[30] nutrition, including baby milk powder, breakfast cereals and energy drinks for humans, also animal feed for poultry, swine and fish. Vitamin B

12 becomes inactive due to hydrogen cyanide and nitric oxide in cigarette smoke. Vitamin B

12 also becomes inactive due to nitrous oxide N

2O commonly known as laughing gas, used for anaesthesia and as a recreational drug.[31] Vitamin B

12 becomes inactive due to microwaving or other forms of heating.[32]

In the cytosol

Methylcobalamin and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate are needed by methionine synthase in the methionine cycle to transfer a methyl group from 5-methyltetrahydrofolate to homocysteine, thereby generating tetrahydrofolate (THF) and methionine, which is used to make SAMe. SAMe is the universal methyl donor and is used for DNA methylation and to make phospholipid membranes, choline, sphingomyelin, acetylcholine, and other neurotransmitters.

In mitochondria

The enzymes that use B

12 as a built-in cofactor are methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (PDB 4REQ[33]) and methionine synthase (PDB 1Q8J).[34]

The metabolism of propionyl-CoA occurs in the mitochondria and requires Vitamin B

12 (as adenosylcobalamin) to make succinyl-CoA. When the conversion of propionyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA in the mitochondria fails due to Vitamin B

12 deficiency, elevated blood levels of methylmalonic acid (MMA) occur. Thus, elevated blood levels of homocysteine and MMA may both be indicators of vitamin B

12 deficiency.

Adenosylcobalamin is needed as cofactor in methylmalonyl-CoA mutase—MUT enzyme. Processing of cholesterol and protein gives propionyl-CoA that is converted to methylmalonyl-CoA, which is used by MUT enzyme to make succinyl-CoA. Vitamin B

12 is needed to prevent anemia, since making porphyrin and heme in mitochondria for producing hemoglobin in red blood cells depends on succinyl-CoA made by vitamin B

12.

Absorption and transport

Poor absorption of vitamin B

12 may be related to coeliac disease. Intestinal absorption of vitamin B

12 requires successively three different protein molecules: haptocorrin, intrinsic factor and transcobalamin II.

Society and culture

Cost

In the United Kingdom it costs the NHS about £2.90 per injection as of 2019.[3] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount was about US$0.77 in 2019.[11]In 2017, it was the 170th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than three million prescriptions.[12][13]

-

Cyanocobalamin costs (US)

-

Cyanocobalamin prescriptions (US)

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Vitamin B12 Injection: Side Effects, Uses & Dosage". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ↑ "Cyanocobalamin – Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2006–2016". ClinCalc.com. Archived from the original on 2019-11-09. Retrieved 2019-11-09.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 993–994. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Cyanocobalamin Side Effects in Detail". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "DailyMed – cyanocobalamin, isopropyl alcohol". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Lilley, Linda Lane; Collins, Shelly Rainforth; Snyder, Julie S. (2019). Pharmacology and the Nursing Process E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 83. ISBN 9780323550468. Archived from the original on 2021-03-09. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Cyanocobalamin - FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ↑ Markle HV (1996). "Cobalamin". Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 33 (4): 247–356. doi:10.3109/10408369609081009. PMID 8875026.

- ↑ Orkin, Stuart H.; Nathan, David G.; Ginsburg, David; Look, A. Thomas; Fisher, David E.; Lux, Samuel (2014). Nathan and Oski's Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 309. ISBN 9780323291774. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Cyanocobalamin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ Cyanocobalamin. University of Maryland Medical Center

- ↑ MacLennan L, Moiemen N (February 2015). "Management of cyanide toxicity in patients with burns". Burns. 41 (1): 18–24. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2014.06.001. PMID 24994676.

- ↑ "Cyanocobalamin Injection". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ "Clinical Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Managing Patients". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ "Vitamin B12". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ Quadros EV (January 2010). "Advances in the understanding of cobalamin assimilation and metabolism". British Journal of Haematology. 148 (2): 195–204. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07937.x. PMC 2809139. PMID 19832808.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Dolphin D (January 1971). McCormick DB, Wright LD (eds.). "[205] Preparation of the reduced forms of vitamin B12 and of some analogs of the vitamin B12 coenzyme containing a cobalt-carbon bond". Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press. 18: 34–52. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(71)18006-8. ISBN 9780121818821.

- ↑ Brodie JD (February 1969). "On the mechanism of catalysis by vitamin B12". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 62 (2): 461–7. Bibcode:1969PNAS...62..461B. doi:10.1073/pnas.62.2.461. PMC 277821. PMID 5256224.

- ↑ Shimakoshi H, Hisaeda Y. "Environmental-friendly catalysts learned from Vitamin B

12-dependent enzymes" (PDF). Tcimail. 128: 2.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Riaz M, Ansari ZA, Iqbal F, Akram M (2007). "Microbial production of vitamin B12 by methanol utilizing strain of Pseudomonas specie". Pak J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1. 40: 5–10. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- ↑ Linnell JC, Matthews DM (February 1984). "Cobalamin metabolism and its clinical aspects". Clinical Science. 66 (2): 113–121. doi:10.1042/cs0660113. PMID 6420106.

- ↑ Herbert V (September 1988). "Vitamin B-12: plant sources, requirements, and assay". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 48 (3 Suppl): 852–8. doi:10.1093/ajcn/48.3.852. PMID 3046314.

- ↑ Zhang, Yemei (January 26, 2009). "New round of price slashing in vitamin B12 sector (Fine and Specialty)". China Chemical Reporter. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Hannibal L, Kim J, Brasch NE, Wang S, Rosenblatt DS, Banerjee R, Jacobsen DW (August 2009). "Processing of alkylcobalamins in mammalian cells: A role for the MMACHC (cblC) gene product". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 97 (4): 260–6. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.04.005. PMC 2709701. PMID 19447654.

- ↑ Watanabe F, Nakano Y (1997). "Purification and characterization of aquacobalamin reductases from mammals". Methods Enzymol. Methods in Enzymology. 281: 295–305. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(97)81036-1. ISBN 9780121821821. PMID 9250994.

- ↑ Quadros EV, Jackson B, Hoffbrand AV, Linnell JC (1979). "Interconversion of cobalamins in human lymphocytes in vitro and the influence of nitrous oxide on the synthesis of cobalamin coenzymes". Vitamin B12, Proceedings of the Third European Symposium on Vitamin B12 and Intrinsic Factor.: 1045–1054.

- ↑ "DSM in Food, Beverages & Dietary Supplements". DSM. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ Thompson AG, Leite MI, Lunn MP, Bennett DL (June 2015). "Whippits, nitrous oxide and the dangers of legal highs". Practical Neurology. 15 (3): 207–9. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2014-001071. PMC 4453489. PMID 25977272.

- ↑ Watanabe F, Abe K, Fujita T, Goto M, Hiemori M, Nakano Y (January 1998). "Effects of Microwave Heating on the Loss of Vitamin B(12) in Foods". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 46 (1): 206–210. doi:10.1021/jf970670x. PMID 10554220.

- ↑ Mancia F, Evans PR (June 1998). "Conformational changes on substrate binding to methylmalonyl CoA mutase and new insights into the free radical mechanism". Structure. 6 (6): 711–20. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00073-2. PMID 9655823. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- ↑ Evans JC, Huddler DP, Hilgers MT, Romanchuk G, Matthews RG, Ludwig ML (March 2004). "Structures of the N-terminal modules imply large domain motions during catalysis by methionine synthase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (11): 3729–36. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.3729E. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308082100. PMC 374312. PMID 14752199. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Drugs with non-standard pregnancy category

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2014

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2019

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2018

- B vitamins

- Organocobalt compounds

- Cofactors

- Vitamin B12

- Corrinoids

- RTT