Calcifediol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(6R)-6-[(1R,3aR,4E,7aR)-4-[(2Z)-2-[(5S)-5-

| |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| MeSH | Calcifediol |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C27H44O2 | |

| Molar mass | 400.64 g/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| H05BX05 (WHO) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

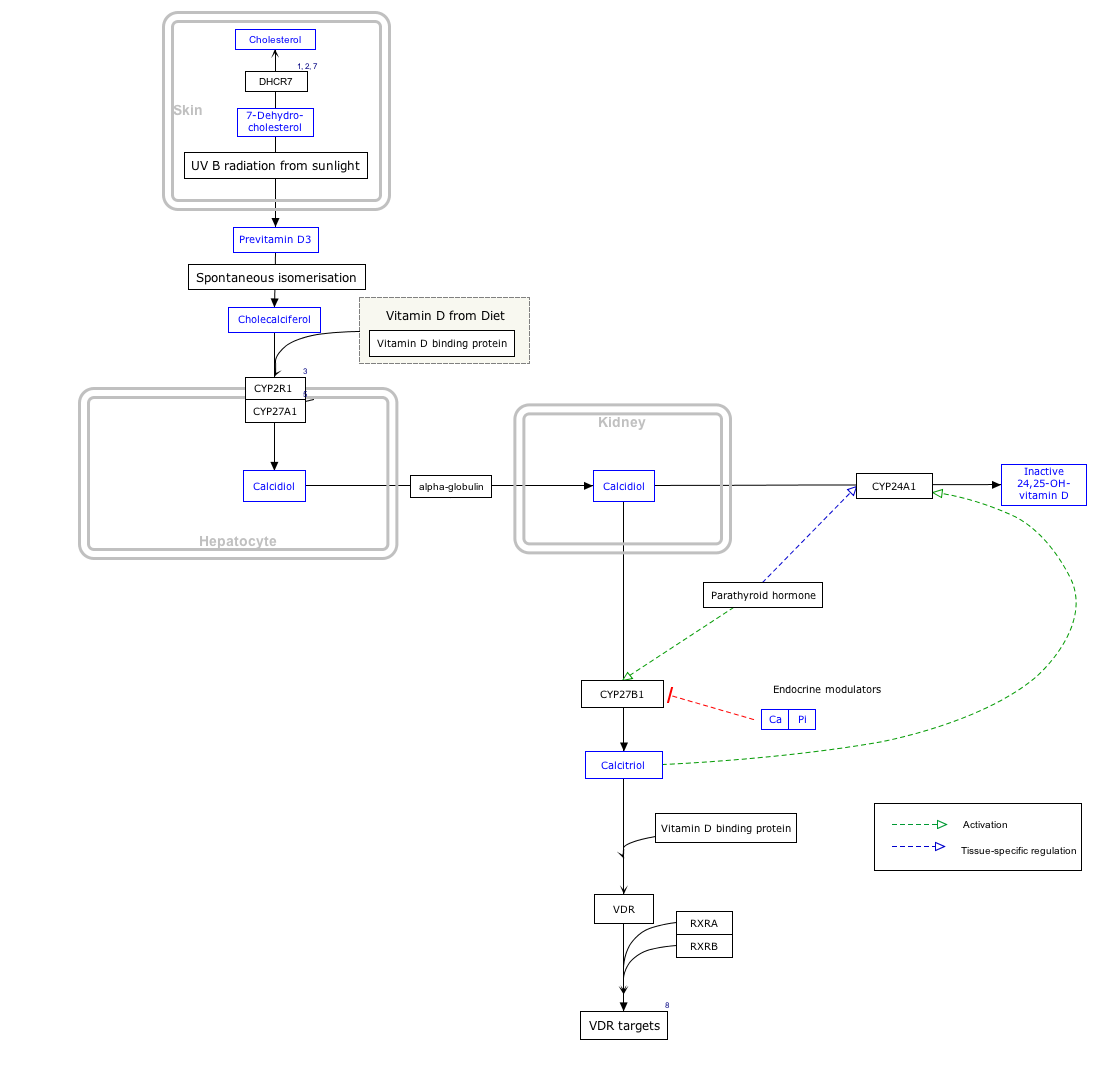

Calcifediol, also known as calcidiol, 25-hydroxycholecalciferol, or 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (abbreviated 25(OH)D3),[1] is a form of vitamin D which is produced in the liver by hydroxylation of vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) by the enzyme vitamin D 25-hydroxylase.[2][3] Calcifediol can be further hydroxylated by the enzyme 25(OH)D-1α-hydroxylase, primarily in the kidney, to form calcitriol (1,25-(OH)2D3), which is the active hormonal form of vitamin D.[2][3]

Calcifediol is strongly bound in blood by the vitamin D-binding protein.[3] Measurement of serum calcifediol is the usual test performed to determine a person's vitamin D status, to show vitamin D deficiency or sufficiency.[2][3] Calcifediol is available as an oral medication in some countries to supplement vitamin D status.[2][4][5]

Biology

Calcifediol is the precursor for calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D.[2] It is synthesized in the liver, by hydroxylation of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) at the 25-position. This enzymatic 25-hydroxylase reaction is mostly due to the actions of CYP2R1, present in microsomes, although other enzymes such as mitochondrial CYP27A1 can contribute.[3][6] Variations in the expression and activity of CYP2R1, such as low levels in obesity, affect circulating calcifediol.[6] Similarly, vitamin D2, ergocalciferol, can also be 25-hydroxylated to form 25-hydroxyergocalciferol, (ercalcidiol, 25(OH)D2);[1] both forms are measured together in blood as 25(OH)D.[2]

At a typical daily oral intake of vitamin D3, full conversion to calcifediol takes approximately 7 days.[7] Calcifediol binds in the blood to vitamin D-binding protein (also known as gc-globulin) and is the main circulating vitamin D metabolite.[2][3] Calcifediol has an elimination half-life of around 15 to 30 days.[2][7]

Calcifediol is further hydroxylated at the 1-alpha-position in the kidneys to form 1,25-(OH)2D3, calcitriol.[2] This enzymatic 25(OH)D-1α-hydroxylase reaction is performed exclusively by CYP27B1, which is highly expressed in the kidneys where it is principally regulated by parathyroid hormone, but also by FGF23 and calcitriol itself.[3][6] CYP27B1 is also expressed in a number of other tissues, including macrophages, monocytes, keratinocytes, placenta and parathyroid gland and extra-renal synthesis of calcitriol from calcifediol has been shown to have biological effects in these tissues.[6][8]

Calcifediol is also be converted into 24,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol by 24-hydroxylation. This enzymatic reaction is performed by CYP24A1 which is expressed in many vitamin D target tissues including kidney, and is induced by calcitriol.[3] This will inactivate calcitriol to calcitroic acid, but 24,25-(OH)2D3 may have some biological actions itself.[3]

Blood test for vitamin D deficiency

In medical practice, a blood test for 25-hydroxy-vitamin D, 25(OH)D, is used to determine an individual's vitamin D status.[9] The name 25(OH)D refers to any combination of calcifediol (25-hydroxy-cholecalciferol), derived from vitamin D3, and ercalcidiol (25-hydroxy-ergocalciferol),[1] derived from vitamin D2. The first of these (also known as 25-hydroxy vitamin D3) is made by the body, or is sourced from certain animal foods or cholecalciferol supplements. The second (25-hydroxy vitamin D2) is from certain vegetable foods or ergocalciferol supplements.[9] Clinical tests for 25(OH)D often measure the total level of both of these two compounds together, generally without differentiating.[10]

This measurement is considered the best indicator of overall vitamin D status.[9][11][12] US labs generally report 25(OH)D levels as ng/mL. Other countries use nmol/L. Multiply ng/mL by 2.5 to convert to nmol/L.[2]

This test can be used to diagnose vitamin D deficiency, and is performed in people with high risk for vitamin D deficiency, when the results of the test can be used to support beginning replacement therapy with vitamin D supplements.[2][13] Patients with osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, malabsorption, obesity, and some other infections may be at greater risk for being vitamin D-deficient and so are more likely to have this test.[13] Although vitamin D deficiency is common in some populations including those living at higher latitudes or with limited sun exposure, the 25(OH)D test is not usually requested for the entire population.[13] Physicians may advise low risk patients to take over-the-counter vitamin D supplements in place of having screening.[13]

It is the most sensitive measure, though experts have called for improved standardization and reproducibility across different laboratories.[2][11] According to MedlinePlus, the recommended range of 25(OH)D is 20 to 40 ng/mL (50 to 100 nmol/L) though they recognize many experts recommend 30 to 50 ng/mL (75 to 125 nmol/L).[9] The normal range varies widely depending on several factors, including age and geographic location. A broad reference range of 20 to 150 nmol/L (8-60 ng/mL) has also been suggested,[14] while other studies have defined levels below 80 nmol/L (32 ng/mL) as indicative of vitamin D deficiency.[15]

Increasing calcifediol levels up to levels of 80 nmol/L (32 ng/mL) are associated with increasing the fraction of calcium that is absorbed from the gut.[11] Urinary calcium excretion balances intestinal calcium absorption and does not increase with calcifediol levels up to ~400 nmol/L (160 ng/mL).[16]

Supplementation

Calcifediol supplements have been used in some studies to improve vitamin D status.[2] Indications for their use include vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency, refractory rickets (vitamin D resistant rickets), familial hypophosphatemia, hypoparathyroidism, hypocalcemia and renal osteodystrophy and, with calcium, in primary or corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis.[17]

Calcifediol may have advantages over cholecalciferol for the correction of vitamin D deficiency states.[4] A review of the results of nine randomized control trials which compared oral doses of both, found that calcifediol was 3.2-fold more potent than cholecalciferol.[4] Calcifediol is better absorbed from the intestine and has greater affinity for the vitamin-D-binding protein, both of which increase its bioavailability.[18] Orally administered calcifediol has a much shorter half-life with faster elimination.[18] These properties may be beneficial in people with intestinal malabsorption, obesity, or treated with certain other medications.[18]

In 2016, the FDA approved a formulation of calcifediol (Rayaldee) 60 microgram daily as a prescription medication to treat secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients with chronic kidney disease.[5]

Interactive pathway map

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

- ↑ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "VitaminDSynthesis_WP1531".

History

Research in the laboratory of Hector DeLuca identified 25(OH)D in 1968 and showed that the liver was necessary for its formation.[19] The enzyme responsible for this synthesis, cholecalciferol 25-hydroxylase, was isolated in the same laboratory by Michael F. Holick in 1972.[20]

A notable 2010 research study by Cedric Garland and Frank C. Garland of the University of California, San Diego analyzed the blood from 25,000 volunteers from Washington County, Maryland, finding that those with the highest levels of calcifediol had a risk of colon cancer that was one-fifth of typical rates.[21]

Research

Studies are ongoing comparing the effects of calcifediol with other forms of vitamin D including cholecalciferol in prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.[18]

A number of clinical trials are underway in different countries to address the potential for calcifediol in the treatment of COVID-19 patients, particularly addressing the acute respiratory distress syndrome.[22][23]

It was noted in a Scientific Advisory Group (SAG) report prepared for the Alberta Health Services that a pilot study "demonstrated that administration of a high dose of Calcifediol ... significantly reduced the need for ICU treatment of patients requiring hospitalization due to proven COVID-19." The SAG decided to suspend judgment for six months as a large number of studies were supposed to report results of different investigations.[24][25]

Society and culture

Cost

In the U.S. extended release 30 mcg goes for $1,207 for 30 capsules[26]

-

Calcifediol costs (US)

-

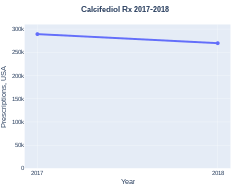

Calcifediol prescriptions (US)

See also

- Hypervitaminosis D

- Hypovitaminosis D

- Vitamin D

- Health effects of Vitamin D

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN): Nomenclature of vitamin D. Recommendations 1981". European Journal of Biochemistry. 124 (2): 223–7. May 1982. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06581.x. PMID 7094913.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 "Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin D". ods.od.nih.gov. 9 October 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Bikle DD (March 2014). "Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications". Chemistry & Biology. 21 (3): 319–29. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.016. PMC 3968073. PMID 24529992.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Quesada-Gomez JM, Bouillon R (August 2018). "Is calcifediol better than cholecalciferol for vitamin D supplementation?". Osteoporosis International (review). 29 (8): 1697–1711. doi:10.1007/s00198-018-4520-y. PMID 29713796.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Rayaldee (calcifediol) FDA Approval History - Drugs.com"". Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Bouillon R, Bikle D (November 2019). "Vitamin D Metabolism Revised: Fall of Dogmas". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research (Review). 34 (11): 1985–1992. doi:10.1002/jbmr.3884. PMID 31589774.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Heaney RP, Armas LA, Shary JR, Bell NH, Binkley N, Hollis BW (June 2008). "25-Hydroxylation of vitamin D3: relation to circulating vitamin D3 under various input conditions". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 87 (6): 1738–42. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1738. PMID 18541563.

- ↑ Adams JS, Hewison M (July 2012). "Extrarenal expression of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-hydroxylase". Arch Biochem Biophys. 523 (1): 95–102. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2012.02.016. PMC 3361592. PMID 22446158.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "25-hydroxy vitamin D test: Medline Plus" Archived 2016-07-05 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ↑ "25HDN - Clinical: 25-Hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3, Serum". Mayo Clinic Labs. 2021. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Heaney RP (December 2004). "Functional indices of vitamin D status and ramifications of vitamin D deficiency". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 80 (6 Suppl): 1706S–9S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1706S. PMID 15585791.

- ↑ Theodoratou E, Tzoulaki I, Zgaga L, Ioannidis JP (April 2014). "Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials". BMJ. 348: g2035. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2035. PMC 3972415. PMID 24690624.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 American Society for Clinical Pathology, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Society for Clinical Pathology, archived from the original on April 8, 2015, retrieved August 1, 2013, which cites

- Sattar N, Welsh P, Panarelli M, Forouhi NG (January 2012). "Increasing requests for vitamin D measurement: costly, confusing, and without credibility". Lancet. 379 (9811): 95–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61816-3. PMID 22243814. S2CID 12669468.

- Bilinski KL, Boyages SC (July 2012). "The rising cost of vitamin D testing in Australia: time to establish guidelines for testing". The Medical Journal of Australia. 197 (2): 90. doi:10.5694/mja12.10561. PMID 22794049. S2CID 45880893.

- Lu CM (May 2012). "Pathology consultation on vitamin D testing: clinical indications for 25(OH) vitamin D measurement". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. American Society for Clinical Pathology. 137 (5): 831–2. doi:10.1309/ajcp2gp0ghkqrcoe. PMID 22645788., which cites

- Arya SC, Agarwal N (May 2012). "The measurement of vitamin D₃requires maintaining quality control". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 137 (5): 832, author reply 833. doi:10.1309/AJCP2GP0GHKQRCOE. PMID 22523224.

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. (July 2011). "Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 96 (7): 1911–30. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0385. PMID 21646368.

- ↑ Bender DA (2003). "Vitamin D". Nutritional biochemistry of the vitamins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80388-5. Retrieved December 10, 2008 through Google Book Search.

- ↑ Hollis BW (February 2005). "Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency: implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake recommendation for vitamin D". The Journal of Nutrition. 135 (2): 317–22. doi:10.1093/jn/135.2.317. PMID 15671234.

- ↑ Kimball SM, Ursell MR, O'Connor P, Vieth R (September 2007). "Safety of vitamin D3 in adults with multiple sclerosis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 86 (3): 645–51. doi:10.1093/ajcn/86.3.645. PMID 17823429.

- ↑ "Calcifediol". go.drugbank.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Cesareo R, Falchetti A, Attanasio R, Tabacco G, Naciu AM, Palermo A (May 2019). "Hypovitaminosis D: Is It Time to Consider the Use of Calcifediol?". Nutrients (Review). 11 (5). doi:10.3390/nu11051016. PMC 6566727. PMID 31064117.

- ↑ Ponchon G, Kennan AL, DeLuca HF (November 1969). ""Activation" of vitamin D by the liver". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 48 (11): 2032–7. doi:10.1172/JCI106168. PMC 297455. PMID 4310770.

- ↑ Holick MF, DeLuca HF, Avioli LV (January 1972). "Isolation and identification of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol from human plasma". Archives of Internal Medicine. 129 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1001/archinte.1972.00320010060005. PMID 4332591.

- ↑ Maugh II, Thomas H. "Frank C. Garland dies at 60; epidemiologist helped show importance of vitamin D: Garland and his brother Cedric were the first to demonstrate that vitamin D deficiencies play a role in cancer and other diseases." Archived 2012-02-05 at the Wayback Machine, Los Angeles Times, August 31, 2010. Accessed September 4, 2010.

- ↑ Quesada-Gomez JM, Entrenas-Castillo M, Bouillon R (September 2020). "Vitamin D receptor stimulation to reduce acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients with coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 infections: Revised Ms SBMB 2020_166". J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol (Review). 202: 105719. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105719. PMC 7289092. PMID 32535032.

- ↑ "International clinical trials assessing calcifediol in people with COVID-19". ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Library of Medicine. May 2020. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ↑ "Vitamin D in the Treatment and Prevention of COVID-19" (PDF). Alberta Health Services. COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group Rapid Evidence Brief. 7 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ↑ Entrenas Castillo M, Entrenas Costa LM, Vaquero Barrios JM, Alcalá Díaz JF, López Miranda J, Bouillon R, Quesada Gomez JM (October 2020). ""Effect of calcifediol treatment and best available therapy versus best available therapy on intensive care unit admission and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: A pilot randomized clinical study"". J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 203: 105751. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105751. PMC 7456194. PMID 32871238.

- ↑ "Rayaldee Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

External links

- "Calcifediol". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2021-03-19.

- Pages with script errors

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles without KEGG source

- Chembox CAS registry number linked

- Articles with changed EBI identifier

- Articles with changed ChemSpider identifier

- Articles with changed InChI identifier

- Pages using collapsible list with both background and text-align in titlestyle

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Portal templates with all redlinked portals

- Vitamin D

- Secosteroids