Anxiety disorder

| Anxiety disorder | |

|---|---|

| |

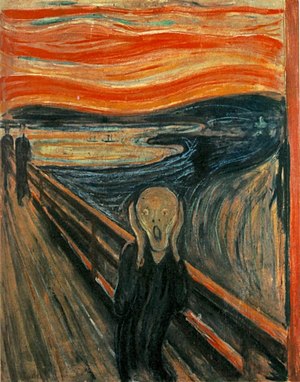

| The Scream (Norwegian: Skrik) a painting by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch[1] | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

| Symptoms | Worrying, fast heart rate, shakiness[2] |

| Complications | Depression, trouble sleeping, poor quality of life, suicide[3] |

| Usual onset | 15–35 years old[4] |

| Duration | > 6 months[2][4] |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors[5] |

| Risk factors | Child abuse, family history, poverty[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Psychological assessment |

| Differential diagnosis | Hyperthyroidism; heart disease; caffeine, alcohol, cannabis use; withdrawal from certain drugs[4][6] |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, counselling, medications[4] |

| Medication | Antidepressants, anxiolytics, beta blockers[5] |

| Frequency | 12% per year[4][7] |

Anxiety disorders are a group of mental disorders characterized by significant feelings of anxiety and fear.[2] Anxiety is a worry about future events, while fear is a reaction to current events.[2] These feelings may cause physical symptoms, such as increased heart rate and shakiness.[2] There are several anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic disorder, and selective mutism.[2] The disorder differs by what results in the symptoms.[2] An individual may have more than one anxiety disorder.[2]

The cause of anxiety disorders is thought to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors.[5] Risk factors include a history of child abuse, family history of mental disorders, and poverty.[4] Anxiety disorders often occur with other mental disorders, particularly major depressive disorder, personality disorder, and substance use disorder.[4] To be diagnosed, symptoms typically need to be present for at least 6 months, be more than what would be expected for the situation, and decrease a person's ability to function in their daily life.[2][4] Other problems that may result in similar symptoms include hyperthyroidism; heart disease; caffeine, alcohol, or cannabis use; and withdrawal from certain drugs, among others.[4][6] Anxiety disorders differ from normal fear or anxiety by being excessive or persisting.[2]

Without treatment, anxiety disorders tend to remain.[2][5] Treatment may include lifestyle changes, counselling, and medications.[4] Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the most common counselling techniques used in treatment of anxiety disorders.[4] Medications, such as antidepressants, benzodiazepines, or beta blockers, may improve symptoms.[5]

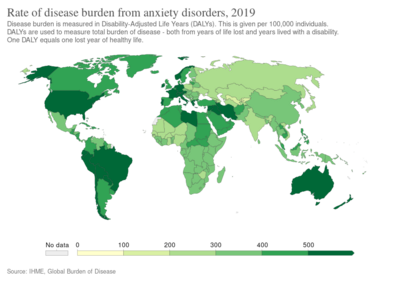

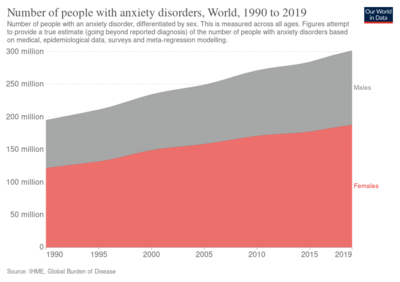

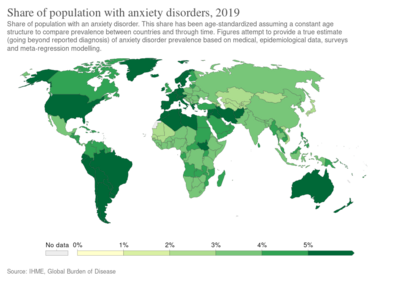

About 12% of people are affected by an anxiety disorder in a given year, and between 5% and 30% are affected over a lifetime.[4][7] They occur in females about twice as often as in males and generally begin before age 25.[2][4] The most common are specific phobias, which affect nearly 12%, and social anxiety disorder, which affects 10%.[4] Phobias mainly affect people between the ages of 15 and 35, and become less common after age 55.[4] Rates appear to be higher in the United States and Europe than in other parts of the world.[4]

Classification

Generalized anxiety disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a common disorder, characterized by long-lasting anxiety which is not focused on any one object or situation. Those suffering from generalized anxiety disorder experience non-specific persistent fear and worry, and become overly concerned with everyday matters. Generalized anxiety disorder is "characterized by chronic excessive worry accompanied by three or more of the following symptoms: restlessness, fatigue, concentration problems, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance".[8] Generalized anxiety disorder is the most common anxiety disorder to affect older adults.[9] Anxiety can be a symptom of a medical or substance abuse problem, and medical professionals must be aware of this. A diagnosis of GAD is made when a person has been excessively worried about an everyday problem for six months or more.[10] A person may find that they have problems making daily decisions and remembering commitments as a result of lack of concentration/preoccupation with worry.[11] Appearance looks strained, with increased sweating from the hands, feet, and axillae,[12] and they may be tearful, which can suggest depression.[13] Before a diagnosis of anxiety disorder is made, physicians must rule out drug-induced anxiety and other medical causes.[14]

In children GAD may be associated with headaches, restlessness, abdominal pain, and heart palpitations.[15] Typically it begins around 8 to 9 years of age.[15]

Specific phobias

The single largest category of anxiety disorders is that of specific phobias which includes all cases in which fear and anxiety are triggered by a specific stimulus or situation. Between 5% and 12% of the population worldwide suffer from specific phobias.[10] Sufferers typically anticipate terrifying consequences from encountering the object of their fear, which can be anything from an animal to a location to a bodily fluid to a particular situation. Common phobias are flying, blood, water, highway driving, and tunnels. When people are exposed to their phobia, they may experience trembling, shortness of breath, or rapid heartbeat.[16] People understand that their fear is not proportional to the actual potential danger but still are overwhelmed by it.[17]

Panic disorder

With panic disorder, a person has brief attacks of intense terror and apprehension, often marked by trembling, shaking, confusion, dizziness, nausea, and/or difficulty breathing. These panic attacks, defined by the APA as fear or discomfort that abruptly arises and peaks in less than ten minutes, can last for several hours.[18] Attacks can be triggered by stress, irrational thoughts, general fear or fear of the unknown, or even exercise. However, sometimes the trigger is unclear and the attacks can arise without warning. To help prevent an attack one can avoid the trigger. This being said not all attacks can be prevented.

In addition to recurrent unexpected panic attacks, a diagnosis of panic disorder requires that said attacks have chronic consequences: either worry over the attacks' potential implications, persistent fear of future attacks, or significant changes in behavior related to the attacks. As such, those suffering from panic disorder experience symptoms even outside specific panic episodes. Often, normal changes in heartbeat are noticed by a panic sufferer, leading them to think something is wrong with their heart or they are about to have another panic attack. In some cases, a heightened awareness (hypervigilance) of body functioning occurs during panic attacks, wherein any perceived physiological change is interpreted as a possible life-threatening illness (i.e., extreme hypochondriasis).

Agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is the specific anxiety about being in a place or situation where escape is difficult or embarrassing or where help may be unavailable.[19] Agoraphobia is strongly linked with panic disorder and is often precipitated by the fear of having a panic attack. A common manifestation involves needing to be in constant view of a door or other escape route. In addition to the fears themselves, the term agoraphobia is often used to refer to avoidance behaviors that sufferers often develop.[20] For example, following a panic attack while driving, someone suffering from agoraphobia may develop anxiety over driving and will therefore avoid driving. These avoidance behaviors can often have serious consequences and often reinforce the fear they are caused by.

Social anxiety disorder

Social anxiety disorder (SAD; also known as social phobia) describes an intense fear and avoidance of negative public scrutiny, public embarrassment, humiliation, or social interaction. This fear can be specific to particular social situations (such as public speaking) or, more typically, is experienced in most (or all) social interactions. Social anxiety often manifests specific physical symptoms, including blushing, sweating, and difficulty speaking. As with all phobic disorders, those suffering from social anxiety often will attempt to avoid the source of their anxiety; in the case of social anxiety this is particularly problematic, and in severe cases can lead to complete social isolation.

Social physique anxiety (SPA) is a subtype of social anxiety. It is concern over the evaluation of one's body by others.[21] SPA is common among adolescents, especially females.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was once an anxiety disorder (now moved to trauma- and stressor-related disorders in DSM-V) that results from a traumatic experience. Post-traumatic stress can result from an extreme situation, such as combat, natural disaster, rape, hostage situations, child abuse, bullying, or even a serious accident. It can also result from long-term (chronic) exposure to a severe stressor--[22] for example, soldiers who endure individual battles but cannot cope with continuous combat. Common symptoms include hypervigilance, flashbacks, avoidant behaviors, anxiety, anger and depression.[23] In addition, individuals may experience sleep disturbances.[24] There are a number of treatments that form the basis of the care plan for those suffering with PTSD. Such treatments include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), psychotherapy and support from family and friends.[10]

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) research began with Vietnam veterans, as well as natural and non natural disaster victims. Studies have found the degree of exposure to a disaster has been found to be the best predictor of PTSD.[25]

Separation anxiety disorder

Separation anxiety disorder (SepAD) is the feeling of excessive and inappropriate levels of anxiety over being separated from a person or place. Separation anxiety is a normal part of development in babies or children, and it is only when this feeling is excessive or inappropriate that it can be considered a disorder.[26] Separation anxiety disorder affects roughly 7% of adults and 4% of children, but the childhood cases tend to be more severe; in some instances, even a brief separation can produce panic.[27][28] Treating a child earlier may prevent problems. This may include training the parents and family on how to deal with it. Often, the parents will reinforce the anxiety because they do not know how to properly work through it with the child. In addition to parent training and family therapy, medication, such as SSRIs, can be used to treat separation anxiety.[29]

Situational anxiety

Situational anxiety is caused by new situations or changing events. It can also be caused by various events that make that particular individual uncomfortable. Its occurrence is very common. Often, an individual will experience panic attacks or extreme anxiety in specific situations. A situation that causes one individual to experience anxiety may not affect another individual at all. For example, some people become uneasy in crowds or tight spaces, so standing in a tightly packed line, say at the bank or a store register, may cause them to experience extreme anxiety, possibly a panic attack.[30] Others, however, may experience anxiety when major changes in life occur, such as entering college, getting married, having children, etc.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is not classified as an anxiety disorder by the DSM-5 but is by the ICD-10. It was previously classified as an anxiety disorder in the DSM-IV. It is a condition where the person has obsessions (distressing, persistent, and intrusive thoughts or images) and compulsions (urges to repeatedly perform specific acts or rituals), that are not caused by drugs or physical disorder, and which cause distress or social dysfunction.[31][32] The compulsive rituals are personal rules followed to relieve the feeling of discomfort.[32] OCD affects roughly 1–2% of adults (somewhat more women than men), and under 3% of children and adolescents.[31][32]

A person with OCD knows that the symptoms are unreasonable and struggles against both the thoughts and the behavior.[31][33] Their symptoms could be related to external events they fear (such as their home burning down because they forget to turn off the stove) or worry that they will behave inappropriately.[33]

It is not certain why some people have OCD, but behavioral, cognitive, genetic, and neurobiological factors may be involved.[32] Risk factors include family history, being single (although that may result from the disorder), and higher socioeconomic class or not being in paid employment.[32] Of those with OCD about 20% of people will overcome it, and symptoms will at least reduce over time for most people (a further 50%).[31]

Selective mutism

Selective mutism (SM) is a disorder in which a person who is normally capable of speech does not speak in specific situations or to specific people. Selective mutism usually co-exists with shyness or social anxiety.[34] People with selective mutism stay silent even when the consequences of their silence include shame, social ostracism or even punishment.[35] Selective mutism affects about 0.8% of people at some point in their life.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Anxiety disorders maybe a severe and chronic conditions, which can be present from an early age or begin suddenly after a triggering event. They are prone to flare up at times of high stress and are frequently accompanied by symptoms such as headache, sweating, muscle spasms, tachycardia, palpitations, and hypertension, which may lead to fatigue.

Associated conditions

Anxiety disorders often occur along with other mental disorders, in particular depression, which may occur in as many as 60% of people with anxiety disorders. The fact that there is considerable overlap between symptoms of anxiety and depression, and that the same environmental triggers can provoke symptoms in either condition, may help to explain this high rate of comorbidity.[36]

Causes

Drugs

Anxiety and depression can be caused by alcohol abuse, which in most cases improves with prolonged abstinence. Even moderate, sustained alcohol use may increase anxiety levels in some individuals.[37] Caffeine, alcohol, and benzodiazepine dependence can worsen or cause anxiety and panic attacks.[38] Anxiety commonly occurs during the acute withdrawal phase of alcohol and can persist for up to 2 years as part of a post-acute-withdrawal syndrome, in about a quarter of people recovering from alcoholism.[39] In one study in 1988–1990, illness in approximately half of patients attending mental health services at one British hospital psychiatric clinic, for conditions including anxiety disorders such as panic disorder or social phobia, was determined to be the result of alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence. In these patients, an initial increase in anxiety occurred during the withdrawal period followed by a cessation of their anxiety symptoms.[40]

There is evidence that chronic exposure to organic solvents in the work environment can be associated with anxiety disorders. Painting, varnishing and carpet-laying are some of the jobs in which significant exposure to organic solvents may occur.[41]

Taking caffeine may cause or worsen anxiety disorders,[42][43] including panic disorder.[44][45][46] Those with anxiety disorders can have high caffeine sensitivity.[47][48] Caffeine-induced anxiety disorder is a subclass of the DSM-5 diagnosis of substance/medication-induced anxiety disorder. Substance/medication-induced anxiety disorder falls under the category of anxiety disorders, and not the category of substance-related and addictive disorders, even though the symptoms are due to the effects of a substance.[49]

Cannabis use is associated with anxiety disorders. However, the precise relationship between cannabis use and anxiety still needs to be established.[50][51]

Medical conditions

Occasionally, an anxiety disorder may be a side-effect of an underlying endocrine disease that causes nervous system hyperactivity, such as pheochromocytoma[52][53] or hyperthyroidism.[54]

Stress

Anxiety disorders can arise in response to life stresses, such as financial worries, chronic physical illness, social interaction, ethnicity, and body image, particularly among young adults.[55][56] Anxiety and mental stress in mid-life are risk factors for dementia and cardiovascular diseases during aging.[57][58]

Genetics

Anxiety disorders are more likely among those with family history of anxiety disorders, especially certain types.[59] GAD runs in families and is six times more common in the children of someone with the condition.[60]

While anxiety arose as an adaptation, in modern times it is almost always thought of negatively in the context of anxiety disorders. People with these disorders have highly sensitive systems; hence, their systems tend to overreact to seemingly harmless stimuli. Sometimes anxiety disorders occur in those who have had traumatic youths, demonstrating an increased prevalence of anxiety when it appears a child will have a difficult future.[61] In these cases, the disorder arises as a way to predict that the individual's environment will continue to pose threats.

Persistence of anxiety

At a low level, anxiety is not a bad thing. In fact, the hormonal response to anxiety has evolved as a benefit, as it helps humans react to dangers. Researchers in evolutionary medicine believe this adaptation allows humans to realize there is a potential threat and to act accordingly in order to ensure greatest possibility of protection. It has actually been shown that those with low levels of anxiety have a greater risk of death than those with average levels. This is because the absence of fear can lead to injury or death.[61] Additionally, patients with both anxiety and depression were found to have lower morbidity than those with depression alone.[62] The functional significance of the symptoms associated with anxiety includes: greater alertness, quicker preparation for action, and reduced probability of missing threats.[62] In the wild, vulnerable individuals, for example those who are hurt or pregnant, have a lower threshold for anxiety response, making them more alert.[62] This demonstrates a lengthy evolutionary history of the anxiety response.

Evolutionary mismatch

It has been theorized that high rates of anxiety are a reaction to how the social environment has changed from the Paleolithic era. For example, in the Stone Age there was greater skin-to-skin contact and more handling of babies by their mothers, both of which are strategies that reduce anxiety.[61] Additionally, there is greater interaction with strangers in present times as opposed to interactions solely between close-knit tribes. Researchers posit that the lack of constant social interaction, especially in the formative years, is a driving cause of high rates of anxiety.

Many current cases are likely to have resulted from an evolutionary mismatch, which has been specifically termed a "psychopathogical mismatch". In evolutionary terms, a mismatch occurs when an individual possesses traits that were adapted for an environment that differs from the individual's current environment. For example, even though an anxiety reaction may have been evolved to help with life-threatening situations, for highly sensitized individuals in Westernized cultures simply hearing bad news can elicit a strong reaction.[63]

An evolutionary perspective may provide insight into alternatives to current clinical treatment methods for anxiety disorders. Simply knowing some anxiety is beneficial may alleviate some of the panic associated with mild conditions. Some researchers believe that, in theory, anxiety can be mediated by reducing a patient's feeling of vulnerability and then changing their appraisal of the situation.[63]

Mechanisms

Low levels of GABA, a neurotransmitter that reduces activity in the central nervous system, contribute to anxiety. A number of anxiolytics achieve their effect by modulating the GABA receptors.[64][65][66]

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, the drugs most commonly used to treat depression, are frequently considered as a first line treatment for anxiety disorders.[67]

Amygdala

The amygdala is central to the processing of fear and anxiety, and its function may be disrupted in anxiety disorders.[68] Sensory information enters the amygdala through the nuclei of the basolateral complex (consisting of lateral, basal, and accessory basal nuclei). The basolateral complex processes sensory-related fear memories and communicates their threat importance to memory and sensory processing elsewhere in the brain, such as the medial prefrontal cortex and sensory cortices.

Another important area is the adjacent central nucleus of the amygdala, which controls species-specific fear responses, via connections to the brainstem, hypothalamus, and cerebellum areas. In those with general anxiety disorder, these connections functionally seem to be less distinct, with greater gray matter in the central nucleus. Another difference is that the amygdala areas have decreased connectivity with the insula and cingulate areas that control general stimulus salience, while having greater connectivity with the parietal cortex and prefrontal cortex circuits that underlie executive functions.[68]

The latter suggests a compensation strategy for dysfunctional amygdala processing of anxiety. Researchers have noted "Amygdalofrontoparietal coupling in generalized anxiety disorder patients may ... reflect the habitual engagement of a cognitive control system to regulate excessive anxiety."[68] This is consistent with cognitive theories that suggest the use in this disorder of attempts to reduce the involvement of emotions with compensatory cognitive strategies.

Clinical and animal studies suggest a correlation between anxiety disorders and difficulty in maintaining balance.[69][70][71][72] A possible mechanism is malfunction in the parabrachial area, a brain structure that, among other functions, coordinates signals from the amygdala with input concerning balance.[73]

Anxiety processing in the basolateral amygdala has been implicated with dendritic arborization of the amygdaloid neurons. SK2 potassium channels mediate inhibitory influence on action potentials and reduce arborization. By overexpressing SK2 in the basolateral amygdala, anxiety in experimental animals can be reduced together with general levels of stress-induced corticosterone secretion.[74]

Joseph E. LeDoux and Lisa Feldman Barrett have both sought to separate automatic threat responses from additional associated cognitive activity within anxiety.

Diagnosis

In casual discourse the words "anxiety" and "fear" are often used interchangeably; in clinical usage, they have distinct meanings: "anxiety" is defined as an unpleasant emotional state for which the cause is either not readily identified or perceived to be uncontrollable or unavoidable, whereas "fear" is an emotional and physiological response to a recognized external threat.[75] The umbrella term "anxiety disorder" refers to a number of specific disorders that include fears (phobias) or anxiety symptoms.[2]

The diagnosis of anxiety disorders are based on symptoms,[76] which typically need to be present at least six months, be more than would be expected for the situation, and decrease functioning.[2][4] Several generic anxiety questionnaires can be used to detect anxiety symptoms, such as the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, and the Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale.[76] Other questionnaires combine anxiety and depression measurement, such as the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS).[76] Examples of specific anxiety questionnaires include the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS), the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN), the Social Phobia Scale (SPS), and the Social Anxiety Questionnaire (SAQ-A30).[77]

At least one time screening is recommended for women by a number of health professional organizations as of 2020 despite the lack of evidence regarding benefits, harms, and costs.[78]

Differential diagnosis

Anxiety disorders differ from developmentally normal fear or anxiety by being excessive or persisting beyond developmentally appropriate periods. They differ from transient fear or anxiety, often stress-induced, by being persistent (e.g., typically lasting 6 months or more), although the criterion for duration is intended as a general guide with allowance for some degree of flexibility and is sometimes of shorter duration in children.[2]

The diagnosis of an anxiety disorder requires first ruling out an underlying medical cause.[6][75] Diseases that may present similar to an anxiety disorder, including certain endocrine diseases (hypo- and hyperthyroidism, hyperprolactinemia),[4][6][75][79] metabolic disorders (diabetes),[6][80] deficiency states (low levels of vitamin D, B2, B12, folic acid),[6] gastrointestinal diseases (celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, inflammatory bowel disease),[81][82][83] heart diseases,[4][6] blood diseases (anemia),[6] and brain degenerative diseases (Parkinson's disease, dementia, multiple sclerosis, Huntington's disease).[6][84][85][86]

Also, several drugs can cause or worsen anxiety, whether in intoxication, withdrawal, or from chronic use. These include alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, sedatives (including prescription benzodiazepines), opioids (including prescription pain killers and illicit drugs like heroin), stimulants (such as caffeine, cocaine and amphetamines), hallucinogens, and inhalants.[4][87]

Prevention

Focus is increasing on prevention of anxiety disorders.[88] There is tentative evidence to support the use of cognitive behavioral therapy[88] and mindfulness therapy.[89][90] A 2013 review found no effective measures to prevent GAD in adults.[91] A 2017 review found that psychological and educational interventions had a small benefit for the prevention of anxiety.[92][93]

Treatment

Treatment options include lifestyle changes, therapy, and medications. There is no clear evidence as to whether therapy or medication is more effective; the choice of which is up to the person with the anxiety disorder and most choose therapy first.[94] The other may be offered in addition to the first choice or if the first choice fails to relieve symptoms.[94]

Lifestyle and diet

Lifestyle changes include exercise, for which there is moderate evidence for some improvement, regularizing sleep patterns, reducing caffeine intake, and stopping smoking.[94] Stopping smoking has benefits in anxiety as large as or larger than those of medications.[95] Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (such as fish oil) may reduce anxiety, particularly in those with more significant symptoms.[96]

Therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is effective for anxiety disorders and is a first line treatment.[94][97][98][99][100] CBT appears to be equally effective when carried out via the internet.[100][101] While evidence for mental health apps is promising it is preliminary.[102]

Self-help books can contribute to the treatment of people with anxiety disorders.[103]

Mindfulness based programs also appear to be effective for managing anxiety disorders.[104][105] It is unclear if meditation has an effect on anxiety and transcendental meditation appears to be no different than other types of meditation.[106]

A 2015 Cochrane review of Morita therapy for anxiety disorder in adults found not enough evidence to draw a conclusion.[107]

Medications

Medications include SSRIs or SNRIs are first line choices for generalized anxiety disorder.[94][108] There is no good evidence for any member of the class being better than another, so cost often drives drug choice.[94][108] If they are effective, it is recommend that they be continued for at least a year.[109] Stopping these medications results in a greater risk of relapse.[110]

Buspirone and pregabalin are second-line treatments for people who do not respond to SSRIs or SNRIs; there is also evidence that benzodiazepines including diazepam and clonazepam are effective but have fallen out of favor due to the risk of dependence and abuse.[94]

Medications need to be used with care among older adults, who are more likely to have side effects because of coexisting physical disorders. Adherence problems are more likely among older people, who may have difficulty understanding, seeing, or remembering instructions.[9]

In general medications are not seen as helpful in specific phobia but a benzodiazepine is sometimes used to help resolve acute episodes; as 2007 data were sparse for efficacy of any drug.[111]

Alternative medicine

Other remedies have been used or are under research for treating anxiety disorders. As of 2019, there is little evidence for cannabis in anxiety disorders.[112] Kava is under preliminary research for its potential in short-term use by people with mild to moderate anxiety.[113][114] The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends use of kava for mild to moderate anxiety disorders in people not using alcohol or taking other medicines metabolized by the liver, while preferring remedies thought to be natural.[115] Inositol has been found to have modest effects in people with panic disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder.[115] There is insufficient evidence to support the use of St. John's wort, valerian or passionflower.[115]

Children

Both therapy and a number of medications have been found to be useful for treating childhood anxiety disorders.[116] Therapy is generally preferred to medication.[117]

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a good first therapy approach.[117] Studies have gathered substantial evidence for treatments that are not CBT based as being effective forms of treatment, expanding treatment options for those who do not respond to CBT.[117] Although studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of CBT for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents, evidence that it is more effective than treatment as usual, medication, or wait list controls is inconclusive.[118] Like adults, children may undergo psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or counseling. Family therapy is a form of treatment in which the child meets with a therapist together with the primary guardians and siblings.[119] Each family member may attend individual therapy, but family therapy is typically a form of group therapy. Art and play therapy are also used. Art therapy is most commonly used when the child will not or cannot verbally communicate, due to trauma or a disability in which they are nonverbal. Participating in art activities allows the child to express what they otherwise may not be able to communicate to others.[120] In play therapy, the child is allowed to play however they please as a therapist observes them. The therapist may intercede from time to time with a question, comment, or suggestion. This is often most effective when the family of the child plays a role in the treatment.[119][121]

If a medication option is warranted, antidepressants such as SSRIs and SNRIs can be effective.[116] Minor side effects with medications, however, are common.[116]

Prognosis

The prognosis varies on the severity of each case and utilization of treatment for each individual. [122]

If these children are left untreated, they face risks such as poor results at school, avoidance of important social activities, and substance abuse. Children who have an anxiety disorder are likely to have other disorders such as depression, eating disorders, attention deficit disorders both hyperactive and inattentive.

Epidemiology

Globally as of 2010 approximately 273 million (4.5% of the population) had an anxiety disorder.[123] It is more common in females (5.2%) than males (2.8%).[123]

In Europe, Africa and Asia, lifetime rates of anxiety disorders are between 9 and 16%, and yearly rates are between 4 and 7%.[124] In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders is about 29%[125] and between 11 and 18% of adults have the condition in a given year.[124] This difference is affected by the range of ways in which different cultures interpret anxiety symptoms and what they consider to be normative behavior.[126][127] In general, anxiety disorders represent the most prevalent psychiatric condition in the United States, outside of substance use disorder.[128]

Like adults, children can experience anxiety disorders; between 10 and 20 percent of all children will develop a full-fledged anxiety disorder prior to the age of 18,[129] making anxiety the most common mental health issue in young people. Anxiety disorders in children are often more challenging to identify than their adult counterparts owing to the difficulty many parents face in discerning them from normal childhood fears. Likewise, anxiety in children is sometimes misdiagnosed as an attention deficit disorder or, due to the tendency of children to interpret their emotions physically (as stomach aches, head aches, etc.), anxiety disorders may initially be confused with physical ailments.[130]

Anxiety in children has a variety of causes; sometimes anxiety is rooted in biology, and may be a product of another existing condition, such as autism or Asperger's disorder.[131] Gifted children are also often more prone to excessive anxiety than non-gifted children.[132] Other cases of anxiety arise from the child having experienced a traumatic event of some kind, and in some cases, the cause of the child's anxiety cannot be pinpointed.[133]

Anxiety in children tends to manifest along age-appropriate themes, such as fear of going to school (not related to bullying) or not performing well enough at school, fear of social rejection, fear of something happening to loved ones, etc. What separates disordered anxiety from normal childhood anxiety is the duration and intensity of the fears involved.[130]

Error: Dataset name contains invalid characters.

Society and culture

References

- ↑ Peter Aspden (21 April 2012). "So, what does 'The Scream' mean?". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental DisordersAmerican Psychiatric Associati (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. pp. 189–195. ISBN 978-0890425558.

- ↑ "Anxiety disorders - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 Craske, MG; Stein, MB (24 June 2016). "Anxiety". Lancet. 388 (10063): 3048–3059. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30381-6. PMID 27349358.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Anxiety Disorders". NIMH. March 2016. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Testa A, Giannuzzi R, Daini S, Bernardini L, Petrongolo L, Gentiloni Silveri N (2013). "Psychiatric emergencies (part III): psychiatric symptoms resulting from organic diseases" (PDF). Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci (Review). 17 Suppl 1: 86–99. PMID 23436670. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 March 2016.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kessler (2007). "Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative". World Psychiatry. 6 (3): 168–76. PMC 2174588. PMID 18188442.

- ↑ Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., & Wegner, D.M. (2011). Psychology: Second Edition. New York, NY: Worth.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Calleo J, Stanley M (2008). "Anxiety Disorders in Later Life: Differentiated Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies". Psychiatric Times. 26 (8). Archived from the original on 4 September 2009.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Phil Barker (7 October 2003). Psychiatric and mental health nursing: the craft of caring. London: Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-81026-2. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ↑ Psychology, Michael Passer, Ronald Smith, Nigel Holt, Andy Bremner, Ed Sutherland, Michael Vliek (2009) McGrath Hill Education, UK: McGrath Hill Companies Inc. p 790

- ↑ "All About Anxiety Disorders: From Causes to Treatment and Prevention". Archived from the original on 17 February 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ↑ Psychiatry, Michael Gelder, Richard Mayou, John Geddes 3rd ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, c 2005 p. 75

- ↑ Varcarolis. E (2010). Manual of Psychiatric Nursing Care Planning: Assessment Guides, Diagnoses and Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. New York: Saunders Elsevier. p 109.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Keeton, CP; Kolos, AC; Walkup, JT (2009). "Pediatric generalized anxiety disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management". Paediatric Drugs. 11 (3): 171–83. doi:10.2165/00148581-200911030-00003. PMID 19445546.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2017). "Phobias". www.mentalhealth.gov. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ Psychology. Michael Passer, Ronald Smith, Nigel Holt, Andy Bremner, Ed Sutherland, Michael Vliek. (2009) McGrath Hill Higher Education; UK: McGrath Hill companies Inc.

- ↑ "Panic Disorder". Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety, University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015.

- ↑ Craske 2003 Gorman, 2000

- ↑ Jane E. Fisher; William T. O'Donohue (27 July 2006). Practitioner's Guide to Evidence-Based Psychotherapy. Springer. pp. 754. ISBN 978-0387283692.

- ↑ The Oxford Handbook of Exercise Psychology. Oxford University Press. 2012. p. 56. ISBN 9780199930746. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ↑ Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and the Family. Veterans Affairs Canada. 2006. ISBN 978-0-662-42627-1. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ↑ Psychological Disorders Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Psychologie Anglophone

- ↑ Shalev, Arieh; Liberzon, Israel; Marmar, Charles (2017). "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder". New England Journal of Medicine. 376 (25): 2459–2469. doi:10.1056/nejmra1612499. PMID 28636846.

- ↑ Fullerton, Carol (1997). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press Inc. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-88048-751-1.

- ↑ Siegler, Robert (2006). How Children Develop, Exploring Child Develop Student Media Tool Kit & Scientific American Reader to Accompany How Children Develop. New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 0-7167-6113-0.

- ↑ Arehart-Treichel, Joan (2006). "Adult Separation Anxiety Often Overlooked Diagnosis – Arehart-Treichel 41 (13): 30 – Psychiatr News". Psychiatric News. 41 (13): 30. doi:10.1176/pn.41.13.0030.

- ↑ Shear, K.; Jin, R.; Ruscio, AM.; Walters, EE.; Kessler, RC. (June 2006). "Prevalence and correlates of estimated DSM-IV child and adult separation anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication". Am J Psychiatry. 163 (6): 1074–1083. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1074. PMC 1924723. PMID 16741209.

- ↑ Mohatt, Justin; Bennett, Shannon M.; Walkup, John T. (1 July 2014). "Treatment of Separation, Generalized, and Social Anxiety Disorders in Youths". American Journal of Psychiatry. 171 (7): 741–748. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101337. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 24874020.

- ↑ Situational Panic Attacks. (n.d.). Retrieved from "Situational Panic Attacks". Archived from the original on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, (UK) (2006). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Core Interventions in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Body Dysmorphic Disorder. NICE Clinical Guidelines. ISBN 9781854334305. PMID 21834191. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 Soomro, GM (18 January 2012). "Obsessive compulsive disorder". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2012. PMC 3285220. PMID 22305974.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). "Obsessive-compulsive disorder: overview". PubMed Health. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Viana, A. G.; Beidel, D. C.; Rabian, B. (2009). "Selective mutism: A review and integration of the last 15 years". Clinical Psychology Review. 29 (1): 57–67. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.009. PMID 18986742.

- ↑ ""The Child Who Would Not Speak a Word"". Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2020. Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Cameron OG (1 December 2007). "Understanding Comorbid Depression and Anxiety". Psychiatric Times. 24 (14). Archived from the original on 20 May 2009.

- ↑ Evans, Katie; Sullivan, Michael J. (1 March 2001). Dual Diagnosis: Counseling the Mentally Ill Substance Abuser (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-57230-446-8.

- ↑ Lindsay, S.J.E.; Powell, Graham E., eds. (28 July 1998). The Handbook of Clinical Adult Psychology (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0-415-07215-1.

- ↑ Johnson, Bankole A. (2011). Addiction medicine : science and practice. New York: Springer. pp. 301–303. ISBN 978-1-4419-0337-2. Archived from the original on 1 December 2015.

- ↑ Cohen SI (February 1995). "Alcohol and benzodiazepines generate anxiety, panic and phobias". J R Soc Med. 88 (2): 73–77. PMC 1295099. PMID 7769598.

- ↑ Morrow LA; et al. (2000). "Increased incidence of anxiety and depressive disorders in persons with organic solvent exposure". Psychosom Med. 62 (6): 746–750. doi:10.1097/00006842-200011000-00002. PMID 11138992. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009.

- ↑ Scott, Trudy (2011). The Antianxiety Food Solution: How the Foods You Eat Can Help You Calm Your Anxious Mind, Improve Your Mood, and End Cravings. New Harbinger Publications. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-57224-926-4. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ↑ Winston AP (2005). "Neuropsychiatric effects of caffeine". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (6): 432–439. doi:10.1192/apt.11.6.432.

- ↑ Hughes RN (June 1996). "Drugs Which Induce Anxiety: Caffeine". New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 25 (1): 36–42. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013.

- ↑ Vilarim MM, Rocha Araujo DM, Nardi AE (August 2011). "Caffeine challenge test and panic disorder: a systematic literature review". Expert Rev Neurother. 11 (8): 1185–95. doi:10.1586/ern.11.83. PMID 21797659.

- ↑ Vilarim, Marina Machado; Rocha Araujo, Daniele Marano; Nardi, Antonio Egidio (2011). "Caffeine challenge test and panic disorder: A systematic literature review". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 11 (8): 1185–95. doi:10.1586/ern.11.83. PMID 21797659.

- ↑ Bruce, Malcolm; Scott, N; Shine, P; Lader, M (1992). "Anxiogenic Effects of Caffeine in Patients with Anxiety Disorders". Archives of General Psychiatry. 49 (11): 867–9. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110031004. PMID 1444724.

- ↑ Nardi, Antonio E.; Lopes, Fabiana L.; Valença, Alexandre M.; Freire, Rafael C.; Veras, André B.; De-Melo-Neto, Valfrido L.; Nascimento, Isabella; King, Anna Lucia; Mezzasalma, Marco A.; Soares-Filho, Gastão L.; Zin, Walter A. (2007). "Caffeine challenge test in panic disorder and depression with panic attacks". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 48 (3): 257–63. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.12.001. PMID 17445520.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 226–230. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ↑ Kedzior, Karina Karolina; Laeber, Lisa Tabata (10 May 2014). "A positive association between anxiety disorders and cannabis use or cannabis use disorders in the general population- a meta-analysis of 31 studies". BMC Psychiatry. 14: 136. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-14-136. ISSN 1471-244X. PMC 4032500. PMID 24884989.

- ↑ Crippa, José Alexandre; Zuardi, Antonio Waldo; Martín-Santos, Rocio; Bhattacharyya, Sagnik; Atakan, Zerrin; McGuire, Philip; Fusar-Poli, Paolo (1 October 2009). "Cannabis and anxiety: a critical review of the evidence". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 24 (7): 515–523. doi:10.1002/hup.1048. ISSN 1099-1077. PMID 19693792.

- ↑ Kantorovich V, Eisenhofer G, Pacak K (2008). "Pheochromocytoma: an endocrine stress mimicking disorder". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1148 (1): 462–8. Bibcode:2008NYASA1148..462K. doi:10.1196/annals.1410.081. PMC 2693284. PMID 19120142.

- ↑ Guller U, Turek J, Eubanks S, Delong ER, Oertli D, Feldman JM (2006). "Detecting pheochromocytoma: defining the most sensitive test". Ann. Surg. 243 (1): 102–7. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000193833.51108.24. PMC 1449983. PMID 16371743.

- ↑ "Thyroid Disease and Mental Disorders: Cause and Effect or Only Comorbidity?". Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ Lijster, Jasmijn M. de; Dierckx, Bram; Utens, Elisabeth M.W.J.; Verhulst, Frank C.; Zieldorff, Carola; Dieleman, Gwen C.; Legerstee, Jeroen S. (24 March 2016). "The Age of Onset of Anxiety Disorders". The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 62 (4): 237–246. doi:10.1177/0706743716640757. ISSN 0706-7437. PMC 5407545. PMID 27310233.

- ↑ Remes, Olivia; Brayne, Carol; van der Linde, Rianne; Lafortune, Louise (5 June 2016). "A systematic review of reviews on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adult populations". Brain and Behavior. 6 (7): e00497. doi:10.1002/brb3.497. ISSN 2162-3279. PMC 4951626. PMID 27458547.

- ↑ Gimson, Amy; Schlosser, Marco; Huntley, Jonathan D; Marchant, Natalie L (2018). "Support for midlife anxiety diagnosis as an independent risk factor for dementia: a systematic review". BMJ Open. 8 (4): e019399. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019399. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 5969723. PMID 29712690.

- ↑ Cohen, Beth E.; Edmondson, Donald; Kronish, Ian M. (24 April 2015). "State of the Art Review: Depression, Stress, Anxiety, and Cardiovascular Disease". American Journal of Hypertension. 28 (11): 1295–1302. doi:10.1093/ajh/hpv047. ISSN 0895-7061. PMC 4612342. PMID 25911639.

- ↑ McLaughlin K; Behar E; Borkovec T (25 August 2005). "Family history of psychological problems in generalized anxiety disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 64 (7): 905–918. doi:10.1002/jclp.20497. PMC 4081441. PMID 18509873. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013.

- ↑ Patel, G; Fancher, TL (3 December 2013). "In the clinic. Generalized anxiety disorder". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (11): ITC6–1, ITC6–2, ITC6–3, ITC6–4, ITC6–5, ITC6–6, ITC6–7, ITC6–8, ITC6–9, ITC6–10, ITC6–11, quiz ITC6–12. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-11-201312030-01006. PMID 24297210.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Grinde, B (2005). "An approach to the prevention of anxiety-related disorders based on evolutionary medicine" (PDF). Preventive Medicine. 40 (6): 904–909. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.08.001. PMID 15850894. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2013.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Bateson, M; B. Brilot; D. Nettle (2011). "Anxiety: An evolutionary approach" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 56 (12): 707–715. doi:10.1177/070674371105601202. PMID 22152639. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2013.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Price, John S. (September 2003). "Evolutionary aspects of anxiety disorders". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 5 (3): 223–236. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-03354-1.50022-5. PMC 3181631. PMID 22033473.

- ↑ Lydiard RB (2003). "The role of GABA in anxiety disorders". J Clin Psychiatry. 64 (Suppl 3): 21–27. PMID 12662130.

- ↑ Nemeroff CB (2003). "The role of GABA in the pathophysiology and treatment of anxiety disorders". Psychopharmacol Bull. 37 (4): 133–146. PMID 15131523.

- ↑ Enna SJ (1984). "Role of gamma-aminobutyric acid in anxiety". Psychopathology. 17 (Suppl 1): 15–24. doi:10.1159/000284073. PMID 6143341.

- ↑ Dunlop BW, Davis PG (2008). "Combination treatment with benzodiazepines and SSRIs for comorbid anxiety and depression: a review". Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 10 (3): 222–228. doi:10.4088/PCC.v10n0307. PMC 2446479. PMID 18615162.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 Etkin A, Prater KE, Schatzberg AF, Menon V, Greicius MD (2009). "Disrupted amygdalar subregion functional connectivity and evidence of a compensatory network in generalized anxiety disorder". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 66 (12): 1361–1372. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.104. PMID 19996041.

- ↑ Kalueff AV, Ishikawa K, Griffith AJ (10 January 2008). "Anxiety and otovestibular disorders: linking behavioral phenotypes in men and mice". Behav. Brain Res. 186 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.032. PMID 17822783.

- ↑ Nagaratnam N, Ip J, Bou-Haidar P (May–June 2005). "The vestibular dysfunction and anxiety disorder interface: a descriptive study with special reference to the elderly". Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 40 (3): 253–264. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2004.09.006. PMID 15814159.

- ↑ Lepicard EM, Venault P, Perez-Diaz F, Joubert C, Berthoz A, Chapouthier G (20 December 2000). "Balance control and posture differences in the anxious BALB/cByJ mice compared to the non anxious C57BL/6J mice". Behav. Brain Res. 117 (1–2): 185–195. doi:10.1016/S0166-4328(00)00304-1. PMID 11099772.

- ↑ Simon NM, Pollack MH, Tuby KS, Stern TA (June 1998). "Dizziness and panic disorder: a review of the association between vestibular dysfunction and anxiety". Ann Clin Psychiatry. 10 (2): 75–80. doi:10.3109/10401239809147746. PMID 9669539.

- ↑ Balaban CD, Thayer JF (January–April 2001). "Neurological bases for balance-anxiety links". J. Anxiety Disord. 15 (1–2): 53–79. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(00)00042-6. PMID 11388358.

- ↑ Mitra R, Ferguson D, Sapolsky RM (10 February 2009). "SK2 potassium channel overexpression in basolateral amygdala reduces anxiety, stress-induced corticosterone secretion and dendritic arborization". Mol. Psychiatry. 14 (9): 847–855, 827. doi:10.1038/mp.2009.9. PMC 2763614. PMID 19204724.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 World Health Organization (2009). Pharmacological Treatment of Mental Disorders in Primary Health Care (PDF). Geneva. ISBN 978-92-4-154769-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2016.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 Rose M, Devine J (2014). "Assessment of patient-reported symptoms of anxiety". Dialogues Clin Neurosci (Review). 16 (2): 197–211 (Table 1). PMC 4140513. PMID 25152658.

- ↑ Rose M, Devine J (2014). "Assessment of patient-reported symptoms of anxiety". Dialogues Clin Neurosci (Review). 16 (2): 197–211 (Table 2). PMC 4140513. PMID 25152658.

- ↑ Gregory, KD; Chelmow, D; Nelson, HD; Van Niel, MS; Conry, JA; Garcia, F; Kendig, SM; O'Reilly, N; Qaseem, A; Ramos, D; Salganicoff, A; Son, S; Wood, JK; Zahn, C; Women’s Preventive Services, Initiative. (7 July 2020). "Screening for Anxiety in Adolescent and Adult Women: A Recommendation From the Women's Preventive Services Initiative". Annals of internal medicine. 173 (1): 48–56. doi:10.7326/M20-0580. PMID 32510990.

- ↑ Samuels MH (2008). "Cognitive function in untreated hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism". Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes (Review). 15 (5): 429–33. doi:10.1097/MED.0b013e32830eb84c. PMID 18769215.

- ↑ Grigsby AB, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ (2002). "Prevalence of anxiety in adults with diabetes: a systematic review". J Psychosom Res (Systematic Review). 53 (6): 1053–60. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00417-8. PMID 12479986.

- ↑ Zingone F, Swift GL, Card TR, Sanders DS, Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC (April 2015). "Psychological morbidity of celiac disease: A review of the literature". United European Gastroenterol J (Review). 3 (2): 136–45. doi:10.1177/2050640614560786. PMC 4406898. PMID 25922673.

- ↑ Molina-Infante J, Santolaria S, Sanders DS, Fernández-Bañares F (May 2015). "Systematic review: noncoeliac gluten sensitivity". Aliment Pharmacol Ther (Systematic Review). 41 (9): 807–20. doi:10.1111/apt.13155. PMID 25753138.

- ↑ Neuendorf R, Harding A, Stello N, Hanes D, Wahbeh H (2016). "Depression and anxiety in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A systematic review". J Psychosom Res (Systematic Review). 87: 70–80. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.06.001. PMID 27411754.

- ↑ Zhao QF, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, et al. (2016). "The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis". J Affect Disord (Systematic Review). 190: 264–71. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069. PMID 26540080.

- ↑ Wen MC, Chan LL, Tan LC, Tan EK (2016). "Depression, anxiety, and apathy in Parkinson's disease: insights from neuroimaging studies". Eur J Neurol (Review). 23 (6): 1001–19. doi:10.1111/ene.13002. PMC 5084819. PMID 27141858.

- ↑ Marrie RA, Reingold S, Cohen J, Stuve O, Trojano M, Sorensen PS, et al. (2015). "The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". Mult Scler (Systematic Review). 21 (3): 305–17. doi:10.1177/1352458514564487. PMC 4429164. PMID 25583845.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 978-0890425558.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Bienvenu, OJ; Ginsburg, GS (December 2007). "Prevention of anxiety disorders". International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England). 19 (6): 647–54. doi:10.1080/09540260701797837. PMID 18092242.

- ↑ Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, et al. (August 2013). "Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis". Clin Psychol Rev. 33 (6): 763–71. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005. PMID 23796855.

- ↑ Sharma M, Rush SE (July 2014). "Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a stress management intervention for healthy individuals: a systematic review". J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 19 (4): 271–86. doi:10.1177/2156587214543143. PMID 25053754.

- ↑ Patel, G; Fancher, TL (3 December 2013). "In the clinic. Generalized anxiety disorder" (PDF). Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (11): ITC6–1, ITC6–2, ITC6–3, ITC6–4, ITC6–5, ITC6–6, ITC6–7, ITC6–8, ITC6–9, ITC6–10, ITC6–11, quiz ITC6–12. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-11-201312030-01006. PMID 24297210. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2015.

currently there is no evidence on the effectiveness of preventive measures for GAD in adult

- ↑ Moreno-Peral, P; Conejo-Cerón, S; Rubio-Valera, M; Fernández, A; Navas-Campaña, D; Rodríguez-Morejón, A; Motrico, E; Rigabert, A; Luna, JD; Martín-Pérez, C; Rodríguez-Bayón, A; Ballesta-Rodríguez, MI; Luciano, JV; Bellón, JÁ (1 October 2017). "Effectiveness of Psychological and/or Educational Interventions in the Prevention of Anxiety: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression". JAMA Psychiatry. 74 (10): 1021–1029. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2509. PMC 5710546. PMID 28877316.

- ↑ Schmidt, Norman B.; Allan, Nicholas P.; Knapp, Ashley A.; Capron, Dan (2019). "8 - Targeting anxiety sensitivity as a prevention strategy". The Clinician's Guide to Anxiety Sensitivity Treatment and Assessment. Academic Press. pp. 145–178. ISBN 978-0-12-813495-5. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 94.2 94.3 94.4 94.5 94.6 Stein, MB; Sareen, J (19 November 2015). "Clinical Practice: Generalized Anxiety Disorder". The New England Journal of Medicine. 373 (21): 2059–68. doi:10.1056/nejmcp1502514. PMID 26580998.

- ↑ Taylor, G.; McNeill, A.; Girling, A.; Farley, A.; Lindson-Hawley, N.; Aveyard, P. (13 February 2014). "Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 348 (feb13 1): g1151. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1151. PMC 3923980. PMID 24524926.

- ↑ Su, Kuan-Pin; Tseng, Ping-Tao; Lin, Pao-Yen; Okubo, Ryo; Chen, Tien-Yu; Chen, Yen-Wen; Matsuoka, Yutaka J. (2018). "Association of Use of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids With Changes in Severity of Anxiety Symptoms". JAMA Network Open. 1 (5): e182327. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2327. ISSN 2574-3805. PMC 6324500. PMID 30646157.

- ↑ Cuijpers, P; Sijbrandij, M; Koole, S; Huibers, M; Berking, M; Andersson, G (March 2014). "Psychological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis". Clinical Psychology Review. 34 (2): 130–140. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.002. PMID 24487344.

- ↑ Otte, C (2011). "Cognitive behavioral therapy in anxiety disorders: current state of the evidence". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 13 (4): 413–21. PMC 3263389. PMID 22275847.

- ↑ Pompoli, A; Furukawa, TA; Imai, H; Tajika, A; Efthimiou, O; Salanti, G (13 April 2016). "Psychological therapies for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in adults: a network meta-analysis" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD011004. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011004.pub2. PMC 7104662. PMID 27071857. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Olthuis, JV; Watt, MC; Bailey, K; Hayden, JA; Stewart, SH (12 March 2016). "Therapist-supported Internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD011565. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011565.pub2. PMC 7077612. PMID 26968204.

- ↑ E, Mayo-Wilson; P, Montgomery (9 September 2013). "Media-delivered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Behavioural Therapy (Self-Help) for Anxiety Disorders in Adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD005330. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005330.pub4. PMID 24018460.

- ↑ Donker, T; Petrie, K; Proudfoot, J; Clarke, J; Birch, MR; Christensen, H (15 November 2013). "Smartphones for smarter delivery of mental health programs: a systematic review". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 15 (11): e247. doi:10.2196/jmir.2791. PMC 3841358. PMID 24240579.

- ↑ Warren Mansell (1 June 2007). "Reading about self-help books on cognitive-behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders". Psychiatric Bulletin. 31 (6): 238–240. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.107.015743.

- ↑ Roemer L, Williston SK, Eustis EH (November 2013). "Mindfulness and acceptance-based behavioral therapies for anxiety disorders". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 15 (11): 410. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0410-3. PMID 24078067.

- ↑ Lang AJ (May 2013). "What mindfulness brings to psychotherapy for anxiety and depression". Depress Anxiety. 30 (5): 409–12. doi:10.1002/da.22081. PMID 23423991.

- ↑ Krisanaprakornkit, T; Krisanaprakornkit, W; Piyavhatkul, N; Laopaiboon, M (25 January 2006). "Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004998. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004998.pub2. PMID 16437509.

- ↑ Wu, Hui; Yu, Dehua; He, Yanling; Wang, Jijun; Xiao, Zeping; Li, Chunbo (19 February 2015). "Morita therapy for anxiety disorders in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD008619. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008619.pub2. PMID 25695214.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Baldwin, David S; Anderson, Ian M; Nutt, David J; Allgulander, Christer; Bandelow, Borwin; Boer, Johan A den; Christmas, David M; Davies, Simon; Fineberg, Naomi (8 April 2014). "Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology" (PDF). Journal of Psychopharmacology. 28 (5): 403–439. doi:10.1177/0269881114525674. PMID 24713617. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ↑ Batelaan, Neeltje M; Bosman, Renske C; Muntingh, Anna; Scholten, Willemijn D; Huijbregts, Klaas M; van Balkom, Anton J L M (13 September 2017). "Risk of relapse after antidepressant discontinuation in anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of relapse prevention trials". BMJ. 358: j3927. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3927. PMC 5596392. PMID 28903922.

- ↑ Batelaan, NM; Bosman, RC; Muntingh, A; Scholten, WD; Huijbregts, KM; van Balkom, AJLM (13 September 2017). "Risk of relapse after antidepressant discontinuation in anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of relapse prevention trials". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 358: j3927. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3927. PMC 5596392. PMID 28903922.

- ↑ Choy, Y; Fyer, AJ; Lipsitz, JD (April 2007). "Treatment of specific phobia in adults". Clinical Psychology Review. 27 (3): 266–86. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.10.002. PMID 17112646.

- ↑ Black, Nicola; Stockings, Emily; Campbell, Gabrielle; Tran, Lucy T; Zagic, Dino; Hall, Wayne D; Farrell, Michael; Degenhardt, Louisa (October 2019). "Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Psychiatry. 6 (12): 995–1010. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30401-8. PMC 6949116. PMID 31672337.

- ↑ Pittler MH, Ernst E (2003). Pittler MH (ed.). "Kava extract for treating anxiety". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003383. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003383. PMC 6999799. PMID 12535473.

- ↑ Witte S, Loew D, Gaus W (March 2005). "Meta-analysis of the efficacy of the acetonic kava-kava extract WS1490 in patients with non-psychotic anxiety disorders". Phytother Res. 19 (3): 183–188. doi:10.1002/ptr.1609. PMID 15934028.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 115.2 Saeed, SA; Bloch, RM; Antonacci, DJ (15 August 2007). "Herbal and dietary supplements for treatment of anxiety disorders". American Family Physician. 76 (4): 549–56. PMID 17853630.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 116.2 Wang, Zhen; Whiteside, Stephen P. H.; Sim, Leslie; Farah, Wigdan; Morrow, Allison S.; Alsawas, Mouaz; Barrionuevo, Patricia; Tello, Mouaffaa; Asi, Noor; Beuschel, Bradley; Daraz, Lubna; Almasri, Jehad; Zaiem, Feras; Larrea-Mantilla, Laura; Ponce, Oscar J.; LeBlanc, Annie; Prokop, Larry J.; Murad, Mohammad Hassan (31 August 2017). "Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Pharmacotherapy for Childhood Anxiety Disorders". JAMA Pediatrics. 171 (11): 1049–1056. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3036. PMC 5710373. PMID 28859190.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 117.2 Higa-McMillan, CK; Francis, SE; Rith-Najarian, L; Chorpita, BF (18 June 2015). "Evidence Base Update: 50 Years of Research on Treatment for Child and Adolescent Anxiety". Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 45 (2): 91–113. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1046177. PMID 26087438.

- ↑ James, Anthony C.; James, Georgina; Cowdrey, Felicity A.; Soler, Angela; Choke, Aislinn (18 February 2015). "Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD004690. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004690.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6491167. PMID 25692403.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 Creswell, Cathy; Cruddace, Susan; Gerry, Stephen; Gitau, Rachel; McIntosh, Emma; Mollison, Jill; Murray, Lynne; Shafran, Rosamund; Stein, Alan (25 May 2015). "Treatment of childhood anxiety disorder in the context of maternal anxiety disorder: a randomised controlled trial and economic analysis". Health Technology Assessment. 19 (38): 1–184. doi:10.3310/hta19380. PMC 4781330. PMID 26004142.

- ↑ Kozlowska K.; Hanney L. (1999). "Family assessment and intervention using an interactive are exercise". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy. 20 (2): 61–69. doi:10.1002/j.1467-8438.1999.tb00358.x.

- ↑ Bratton, S.C., & Ray, D. (2002). Humanistic play therapy. In D.J. Cain (Ed.), Humanistic psychotherapies: Handbook of research and practice (pp. 369-402). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ Stanford University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences (2002). Principles and Practice of Geriatric Psychology, Second Edition. Principles and Practice of Geriatric Psychiatry. pp. 555–557. doi:10.1002/0470846410.ch101. ISBN 978-0471981978.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Vos, T; Flaxman, AD; Naghavi, M; Lozano, R; Michaud, C; Ezzati, M; Shibuya, K; Salomon, JA; Abdalla, S; et al. (15 December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Simpson, Helen Blair, ed. (2010). Anxiety disorders : theory, research, and clinical perspectives (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-521-51557-3. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- ↑ Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (June 2005). "Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 62 (6): 593–602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. PMID 15939837.

- ↑ Brockveld, Kelia C.; Perini, Sarah J.; Rapee, Ronald M. (2014). "6". In Hofmann, Stefan G.; DiBartolo, Patricia M. (eds.). Social Anxiety: Clinical, Developmental, and Social Perspectives (3 ed.). Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-394427-6.00006-6. ISBN 978-0-12-394427-6.

- ↑ Hofmann, Stefan G.; Asnaani, Anu (December 2010). "Cultural Aspects in Social Anxiety and Social Anxiety Disorder". Depress Anxiety. 27 (12): 1117–1127. doi:10.1002/da.20759. PMC 3075954. PMID 21132847.

- ↑ Fricchione, Gregory (12 August 2004). "Generalized Anxiety Disorder". New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (7): 675–682. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp022342. PMID 15306669.

- ↑ Essau, Cecilia A. (2006). Child and Adolescent Psychopathology: Theoretical and Clinical Implications. 27 church road, Hove, East Sussex: Routledge. p. 79.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ 130.0 130.1 AnxietyBC (14 November 2014). "GENERALIZED ANXIETY". AnxietyBC. AnxietyBC. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Merrill, Anna. "Anxiety and Autism Spectrum Disorders". Indiana Resource Center for Autism. Indiana Resource Center for Autism. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ Guignard, Jacques-Henri; Jacquet, Anne-Yvonne; Lubart, Todd I. (2012). "Perfectionism and Anxiety: A Paradox in Intellectual Giftedness?". PLOS ONE. 7 (7): e41043. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...741043G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041043. PMC 3408483. PMID 22859964.

- ↑ Rapee, Ronald M.; Schniering, Carolyn A.; Hudson, Jennifer L. "Anxiety Disorders During Childhood and Adolescence: Origins and Treatment" (PDF). Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2015.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Support Group Providers for Anxiety disorder at Curlie

- Khouzam, HR (March 2009). "Anxiety Disorders: Guidelines for Effective Primary Care. Part 1: Diagnosis". Consultant. 49 (3). Archived from the original on 2 August 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Khouzam, HR (April 2009). "Anxiety Disorders: Guidelines for Effective Primary Care. Part 2: Treatment". Consultant. 49 (4). Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Pages with script errors

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1: long volume value

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 maint: location

- Use dmy dates from June 2015

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with Curlie links

- Abnormal psychology

- Anxiety disorders

- Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders

- Psychiatric diagnosis

- RTT

- RTTNEURO

- WHRTT