Anti-Hu associated encephalitis

| Anti-Hu associated encephalitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Anti-ANNA1 associated encephalitis | |

| |

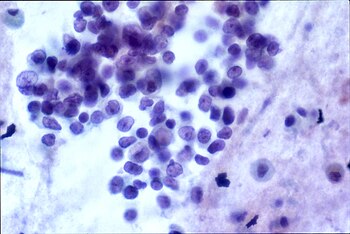

| Histopathology of small cell carcinoma of the lung, which is strongly associated with anti-Hu antibodies. | |

| Symptoms | Depression, anxiety, hallucinations, confusion, memory loss, weakness, numbness, ataxia, seizures, pain |

| Causes | Paraneoplastic syndrome |

| Risk factors | Smoking, male gender |

| Diagnostic method | Western blot, EEG, MRI |

| Differential diagnosis | Autoimmune encephalitis, metastatic cancer, viral encephalitis, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, cerebrovascular disease, Whipple disease, schizophrenia, toxic-metabolic encephalopathy, Wernicke encephalopathy, dementia, multiple sclerosis, Behçet's disease |

| Treatment | Immunotherapy, chemotherapy |

| Prognosis | Average survival less than 12 months |

Anti-Hu associated encephalitis, also known as Anti-ANNA1 associated encephalitis, is an uncommon form of brain inflammation that is associated with an underlying cancer. It can cause psychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and hallucinations.[1] It can also produce neurological symptoms such as confusion, memory loss, weakness, sensory loss, pain, seizures, and problems coordinating the movement of the body.[2]

While its cause is unknown, the most common hypothesis is that it is caused by an immune system attack on the nervous system. This immune system attack is linked to cancer in most cases, usually small cell lung carcinoma. The condition's namesake, the anti-Hu antibody, is a protein made by the host's immune system, and it is present in virtually all cases. Treatment is focused on removing the underlying cancer and suppressing the immune system. Its prognosis remains quite poor, with most patients dying less than a year after diagnosis.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms can vary in onset, quality, duration, severity, and response to treatment. Symptoms tend to present acutely over days to weeks. Its symptoms depend on which areas of the brain the disease affects, because specific parts of the brain have particular functions.[4]

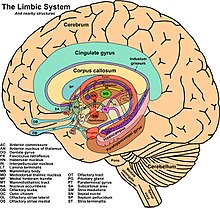

Many cases involve an attack on the limbic system, which includes structures like the amygdala, hippocampus, and thalamus. Respectively these brain regions regulate anger, fear, memory formation, and motor and sensory signaling. Affected persons may develop memory loss and may have sudden changes in personality. This is often accompanied by headaches, delusions, or hallucinations.[5]

In some cases, the antibodies created by this illness attack another structure of the brain called the brainstem. The brainstem is responsible for basic bodily functions like breathing, but not more complex actions and emotions, which is why the presentation is different when the disease affects the limbic system than when it affects the brainstem. Symptoms may include dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and decreased breathing which may progress to respiratory failure.[6][7]

Cause

Anti-Hu associated encephalitis is a syndrome associated with cancer. However, occasionally it occurs without cancer being present. Proteins react within the brain and change behavior and basic biological functions. Primarily adults contract this illness, and typically they have an underlying cancer that is either undiagnosed, diagnosed, in remission, or cured.[3]

The condition can occur at any point during cancer. Small cell lung cancer is a particularly aggressive cancer more common in smokers and is associated with anti-Hu encephalitis. Neuroblastoma is a cancer more frequently affecting children, and despite the relatively low rates of anti-Hu among children with neuroblastoma, these are the most likely children to have anti-Hu associated encephalitis.[8][9]

Pathophysiology

Nearly all people with the condition have anti-Hu antibodies in their serum. The antibody is produced by the body as an immune system response to Hu proteins, which are naturally clustered within the nuclei of neurons in the central and peripheral nervous system. The condition can involve a number of neural structures including the brainstem, cerebellum, spinal cord, dorsal roots, peripheral nerves, and the limbic system of the brain.[1]

There is a debate about whether the antibody is a cause of, rather than an effect of, the disease process. Older studies suggested the antibodies caused the disease, pointing to the discovery of antibody deposition in the brain tissue of patients at autopsy. However, the injection of the antibodies into mice did not produce any disease, and the deposition of antibody was often not at the places where brain damage was greatest.[3] Newer studies suggest the antibodies are an effect, not a cause, of the condition, with a consensus that a patient's own T cells are playing a major role in the disease process. These T cells may be activated by the Hu proteins.[10][11]

In people with cancer, the cancer has a likely role in the cause of the encephalitis. In a paraneoplastic syndrome, a cancer cell can create proteins that are normally only found as naturally-occurring proteins in other cell types in other parts of the body. In patients with small cell carcinoma of the lung, cancer cells in the lung can produce Hu proteins that are usually only found inside of the body's own neurons. It is hypothesized that through these cancer-produced Hu proteins, the body creates an immune system response. This reaction includes T cells, which then attack nervous tissue.[12] The cancer-produced Hu proteins are found in nearly all small-cell lung carcinomas, 70 percent of neuroblastomas, and a small percentage of other tumors.[13]

Diagnosis

Anti-Hu encephalitis is a disease characterized by production of anti-Hu antibodies and rapid development of particular signs and symptoms. Therefore, the diagnosis usually involves detecting its associated psychiatric and neurologic deficits and then performing diagnostic testing. If these signs and symptoms occur in a person who is suspected of having cancer, then anti-Hu associated encephalitis is also suspected. Because small cell lung cancer commonly occurs together with anti-Hu encephalitis, a diagnosis of small cell lung cancer confers a greater suspicion.[1]

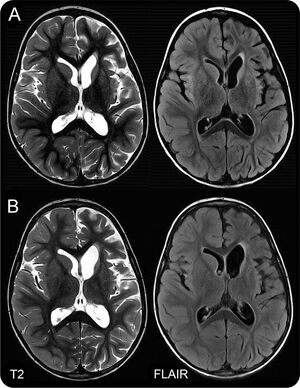

In suspected cases, physicians perform diagnostic testing using a protein-detecting test that identify anti-Hu antibodies, if present. Another test involves examining the fluid that bathes the brain and spine, although this test is less specific for the disease. Physicians may also use a special imaging device, known as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which can take pictures of the patient's brain and detect signs of inflammation that suggest ongoing disease. An electroencephalogram (EEG) is another tool that can be done to clarify whether anti-Hu encephalitis is the underlying cause of a patient's symptoms. This is a test that involves placing probes on a person's head to detect electrical brain activity. Certain patterns of activity can be indicative of brain disease. In the case of anti-Hu encephalitis, temporal lobe electrical activity changes and the length of certain electrical waves known as delta and theta waves become slowed.[1]

Before the diagnosis can be made, other causes of disease need to be ruled out. They could be the sole cause or a co-contributor to a patient's new symptoms, in addition to anti-Hu encephalitis. Examples include—but are not limited to—problems with metabolism, a brain tumor, or inflammation of tissue coating around the brain.[14]

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment involves two broad strategies: treat the cancer that usually occurs with the disease, and give medications that suppress the body's immune system attack on the nervous system. Because current treatments are not successful at eliminating the disease, the goal of treatment is often to reduce symptoms rather than attempt to cure it. To date, treatments have been unsuccessful in achieving a sustained reduction of symptoms or survival in the vast majority of patients.[2]

Some treatments may directly combat the mechanisms by which the disease may be caused. To suppress the immune system, steroids, antibodies, or even human cells may be injected into a patient. Certain types of antibodies called intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) also have shown to lead to reduced symptoms due to their ability to reduce and eliminate anti-Hu antibodies.[15] A drug called rituximab, a molecule that targets B cells, helps reduce the symptoms of anti-Hu encephalitis and decreases the number of anti-Hu antibodies.[16] Cancer treatment may involve surgical removal of the tumor, or medications that may shrink or eliminate the tumor.[17][2] Treatment with cyclophosphamide, a chemotherapy drug, has shown promise, in addition to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).[18][19][2] This hormone is involved in regulating many body functions including stress level and blood pressure. Steroids such as dexamethasone may help reduce disease burden by reducing the antibody-building activity of the disease. Despite the fact that steroids can be used to reduce the immunological antibody-building activity of the disease in all people, many other anti-Hu encephalitis treatments are most effective in children.[15]

Treatments may also be focused purely on symptoms rather than targeting the potential causes of the disease. For seizures, anticonvulsant medications may be used, such as valproic acid, levetiracetam, or lamotrigine. For hallucinations, delusions, and mood disturbances, second generation antipsychotic agents (e.g., olanzapine, clozapine) are also used for symptom control.[2]

Prognosis

Although many patients have an underlying cancer, the prognosis is determined by the severity of the neurological symptoms produced by the encephalitis. Compared to other paraneoplastic encephalitides, anti-Hu associated encephalitis has an especially poor prognosis. Several studies reporting an average survival time of less than a year, from the time of diagnosis. Much of the prognosis depends on the efficacy of treatment, which is directed at the underlying cancer, if present.[20][21][22] Patients with lower titers of the anti-Hu antibody tend to have a better prognosis.[13]

Epidemiology

The typical age at diagnosis is 63 years old. It is three times more common in men than women. Of those diagnosed with the condition, about 85 percent also had a cancer diagnosis, with 86 percent being lung cancers (mostly small-cell carcinoma) and 14 percent being outside the lung (most commonly prostate, gastrointestinal, breast, and bladder cancer).[13] However, other cancers have been known to co-occur with the disease, including spindle cell carcinoma of the sinus and a seminoma of the mediastinum.[23] People with small cell carcinoma often have other diseases caused by an immune response to the cancer, including Cushing syndrome, SIADH, and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome.[24]

History

The condition was first identified in 1985 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center at Cornell University, by three physicians, Francesc Graus, Carlos Cordon-Cardo, and Jerome Posner. They identified the anti-Hu antibody in two patients who had sensory neuronopathy and small cell carcinoma of the lung.[25]

Special populations

Children, in addition to adults, also can develop anti-Hu encephalitis; however, the disease manifests differently in children. As with adults, anti-Hu encephalitis is associated with malignancy. The cancers most associated with anti-Hu encephalitis are neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroblastoma. Opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome (OMS) is a condition that develops in children as a result of anti-Hu antibodies. The illness afflicts younger children, with one study showing an age range of about 2 months to 10 years, with the majority of cases falling between 6 months to 3 years. The first symptoms are nonspecific. For instance, it can present like an upper airway infection, with cough and fever, or like an intestinal infection, with vomiting, diarrhea, and fever. Crying, particularly in younger children, can be an early sign.[26] Other symptoms include problems with eye movement, irritability, and insomnia.[8][9]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kaplan PW, Sutter R (2013). "Electroencephalography of autoimmune limbic encephalopathy". J Clin Neurophysiol. 30 (5): 490–504. doi:10.1097/WNP.0b013e3182a73d47. PMID 24084182. S2CID 24130688. Archived from the original on 2021-09-13. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Dubey D, Blackburn K, Greenberg B, Stuve O, Vernino S (2016). "Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for management of autoimmune encephalopathies". Expert Rev Neurother. 16 (8): 937–49. doi:10.1080/14737175.2016.1189328. PMID 27171736. S2CID 13759612. Archived from the original on 2021-09-13. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Didelot A, Honnorat J (2014). "Paraneoplastic disorders of the central and peripheral nervous systems". Neurologic Aspects of Systemic Disease Part III. Handb Clin Neurol. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 121. pp. 1159–79. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-4088-7.00078-X. ISBN 9780702040887. PMID 24365410. Archived from the original on 2022-11-09. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ Helpman L, Zhu X, Suarez-Jimenez B, Lazarov A, Monk C, Neria Y (2017). "Sex Differences in Trauma-Related Psychopathology: a Critical Review of Neuroimaging Literature (2014-2017)". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 19 (12): 104. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0854-y. PMC 5737777. PMID 29116470.

- ↑ Langer JE, Lopes MB, Fountain NB, Pranzatelli MR, Thiele EA, Rust RS, Goodkin HP (2012). "An unusual presentation of anti-Hu-associated paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis". Dev Med Child Neurol. 54 (9): 863–6. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04221.x. PMID 22320677. S2CID 22388381.

- ↑ Vigliani MC, Novero D, Cerrato P, Daniele D, Crasto S, Berardino M, Mutani R (2009). "Double step paraneoplastic brainstem encephalitis: a clinicopathological study". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 80 (6): 693–5. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.145961. PMID 19448098. S2CID 24747904. Archived from the original on 2023-12-12. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ Najjar M, Taylor A, Agrawal S, Fojo T, Merkler AE, Rosenblum MK, Lennihan L, Kluger MD (2017). "Anti-Hu paraneoplastic brainstem encephalitis caused by a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor presenting with central hypoventilation". J Clin Neurosci. 40: 72–73. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2017.02.015. PMID 28256369. S2CID 26309502. Archived from the original on 2023-05-10. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Blaes F, Fühlhuber V, Preissner KT (2007). "Identification of autoantigens in pediatric opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome". Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 3 (6): 975–82. doi:10.1586/1744666X.3.6.975. PMID 20477144. S2CID 43047140. Archived from the original on 2022-12-23. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Meena JP, Seth R, Chakrabarty B, Gulati S, Agrawala S, Naranje P (2016). "Neuroblastoma presenting as opsoclonus-myoclonus: A series of six cases and review of literature". J Pediatr Neurosci. 11 (4): 373–377. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.199462. PMC 5314861. PMID 28217170.

- ↑ Dalmau J, Rosenfeld MR (2014). "Autoimmune encephalitis update". Neuro Oncol. 16 (6): 771–8. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nou030. PMC 4022229. PMID 24637228.

- ↑ Bernal F, Graus F, Pifarré A, Saiz A, Benyahia B, Ribalta T (2002). "Immunohistochemical analysis of anti-Hu-associated paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis". Acta Neuropathol. 103 (5): 509–15. doi:10.1007/s00401-001-0498-0. PMID 11935268. S2CID 25157807. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ de Jongste AH, de Graaf MT, van den Broek PD, Kraan J, Smitt PA, Gratama JW (2013). "Elevated numbers of regulatory T cells, central memory T cells and class-switched B cells in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with anti-Hu antibody associated paraneoplastic neurological syndromes". J Neuroimmunol. 258 (1–2): 85–90. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.02.006. PMID 23566401. S2CID 38435280. Archived from the original on 2022-05-03. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Graus F, Keime-Guibert F, Reñe R, Benyahia B, Ribalta T, Ascaso C, Escaramis G, Delattre JY (2001). "Anti-Hu-associated paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis: analysis of 200 patients". Brain. 124 (Pt 6): 1138–48. doi:10.1093/brain/124.6.1138. PMID 11353730.

- ↑ Ochenduszko S, Wilk B, Dabrowska J, Herman-Sucharska I, Dubis A, Puskulluoglu M (2017). "Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis in a patient with extensive disease small-cell lung cancer". Mol Clin Oncol. 6 (4): 575–578. doi:10.3892/mco.2017.1162. PMC 5374934. PMID 28413671.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Pranzatelli MR (1996). "The immunopharmacology of the opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome". Clin Neuropharmacol. 19 (1): 1–47. doi:10.1097/00002826-199619010-00001. PMID 8867515. Archived from the original on 2022-12-23. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ Ketterl TG, Messinger YH, Niess DR, Gilles E, Engel WK, Perkins JL (2013). "Ofatumumab for refractory opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome following treatment of neuroblastoma". Pediatr Blood Cancer. 60 (12): E163-5. doi:10.1002/pbc.24646. PMID 23813921. S2CID 12279928. Archived from the original on 2022-06-17. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ Lancaster E (2017). "Paraneoplastic Disorders". Continuum (Minneap Minn). 23 (6, Neuro–oncology): 1653–1679. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000542. PMID 29200116. S2CID 46599983. Archived from the original on 2022-03-13. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ Armstrong MB, Robertson PL, Castle VP (2005). "Delayed, recurrent opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome responding to plasmapheresis". Pediatr Neurol. 33 (5): 365–7. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.05.018. PMID 16243225. Archived from the original on 2023-12-12. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ Blaes F (2013). "Paraneoplastic brain stem encephalitis". Curr Treat Options Neurol. 15 (2): 201–9. doi:10.1007/s11940-013-0221-1. PMID 23378230. S2CID 21581917. Archived from the original on 2023-04-26. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ Huemer F, Melchardt T, Tränkenschuh W, Neureiter D, Moser G, Magnes T, Weiss L, Schlattau A, Hufnagl C, Ricken G, Höftberger R, Greil R, Egle A (2015). "Anti-Hu Antibody Associated Paraneoplastic Cerebellar Degeneration in Head and Neck Cancer". BMC Cancer. 15: 996. doi:10.1186/s12885-015-2020-4. PMC 4687318. PMID 26694863.

- ↑ Shams'ili S, Grefkens J, de Leeuw B, van den Bent M, Hooijkaas H, van der Holt B, Vecht C, Sillevis Smitt P (2003). "Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration associated with antineuronal antibodies: analysis of 50 patients". Brain. 126 (Pt 6): 1409–18. doi:10.1093/brain/awg133. PMID 12764061.

- ↑ Graus F, Dalmou J, Reñé R, Tora M, Malats N, Verschuuren JJ, Cardenal F, Viñolas N, Garcia del Muro J, Vadell C, Mason WP, Rosell R, Posner JB, Real FX (1997). "Anti-Hu antibodies in patients with small-cell lung cancer: association with complete response to therapy and improved survival". J Clin Oncol. 15 (8): 2866–72. doi:10.1200/JCO.1997.15.8.2866. PMID 9256130. Archived from the original on 2023-11-07. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ Pohley I, Roesler K, Wittstock M, Bitsch A, Benecke R, Wolters A (2015). "NMDA-receptor antibody and anti-Hu antibody positive paraneoplastic syndrome associated with a primary mediastinal seminoma". Acta Neurol Belg. 115 (1): 81–3. doi:10.1007/s13760-014-0296-9. PMID 24696410. S2CID 11672970. Archived from the original on 2023-12-12. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ↑ Kanaji N, Watanabe N, Kita N, Bandoh S, Tadokoro A, Ishii T, Dobashi H, Matsunaga T (2014). "Paraneoplastic syndromes associated with lung cancer". World J Clin Oncol. 5 (3): 197–223. doi:10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.197. PMC 4127595. PMID 25114839.

- ↑ Graus F, Cordon-Cardo C, Posner JB (1985). "Neuronal antinuclear antibody in sensory neuronopathy from lung cancer". Neurology. 35 (4): 538–43. doi:10.1212/wnl.35.4.538. PMID 2984600.

- ↑ Pranzatelli MR, Tate ED, McGee NR (2017). "Demographic, Clinical, and Immunologic Features of 389 Children with Opsoclonus-Myoclonus Syndrome: A Cross-sectional Study". Front Neurol. 8: 468. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00468. PMC 5604058. PMID 28959231.