Hypertriglyceridemia

| Hypertriglyceridemia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Triglyceride, which cause hypertriglyceridemia at high level | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Usually none[1] |

| Complications | Cardiovascular disease, pancreatitis[2] |

| Risk factors | Obesity, diabetes, genetics, metabolic syndrome, alcohol[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Triglycerides > 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L)[2] |

| Treatment | Not drinking alcohol, weight loss, avoiding simple carbohydrates, controlling blood sugar[2] |

| Medication | Fibrates, omega-3 fatty acids, insulin[2][3] |

| Frequency | ~30% (USA)[4] |

Hypertriglyceridemia is high (hyper-) blood levels (-emia) of triglycerides.[1] High triglycerides itself is usually symptomless, although high levels may be associated with skin lesions known as xanthomas.[1][5] Complications may include cardiovascular disease and pancreatitis.[2] Generally only severe disease results in pancreatitis.[2] High triglycerides may occur alone or with other lipid disorders.[5]

Most cases result from a combination of factors.[4] Common risk factors include obesity, diabetes, genetics, and metabolic syndrome.[2] Other risks include alcohol, hypothyroidism, kidney problems, lupus, and certain medications such as protease inhibitors and birth control pills.[2][4] Diagnosis is based on fasting triglycerides of greater than than 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L).[2] Moderate disease is 150 to 1,000 mg/dL (1.7 to 11.4 mmol/L) while severe disease is greater than 1,000 mg/dL (>11.4 mmol/L).[2]

Treatment includes not drinking alcohol, weight loss, avoiding simple carbohydrates, and controlling blood sugar.[2] Medications are generally not required, though fibrates and omega-3 fatty acids may help.[2] In those with pancreatitis due to high triglycerides treatment is with intravenous fluids, insulin, and potentially plasmapheresis.[2][3] High blood triglycerides affects about 30% of people in the United States and is more common in males and older people.[4] Very high levels affect about 2% of people.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Most people with elevated triglycerides experience no symptoms. Some forms of primary hypertriglyceridemia can lead to specific symptoms: both familial chylomicronemia and primary mixed hyperlipidemia include skin symptoms (eruptive xanthoma), eye abnormalities (lipemia retinalis), hepatosplenomegaly (enlargement of the liver and spleen), and neurological symptoms. Some experience attacks of abdominal pain that may be mild episodes of pancreatitis. Eruptive xanthomas are 2–5 mm papules, often with a red ring around them, that occur in clusters on the skin of the trunk, buttocks and extremities.[6] Familial dysbetalipoproteinemia causes larger, tuberous xanthomas; these are red or orange and occur on the elbows and knees. Palmar crease xanthomas may also occur.[5][6]

The diagnosis is made on blood tests, often performed as part of screening. Once diagnosed, other blood tests are usually required to determine whether the raised triglyceride level is caused by other underlying disorders ("secondary hypertriglyceridemia") or whether no such underlying cause exists ("primary hypertriglyceridaemia"). There is a hereditary predisposition to both primary and secondary hypertriglyceridemia.[5]

Acute pancreatitis may occur in people whose triglyceride levels are above 1000 mg/dL (11.3 mmol/L).[5][6][7] Hypertriglyceridemia is associated with 1–4% of all cases of pancreatitis. The symptoms are similar to pancreatitis secondary to other causes, although the presence of xanthomas or risk factors for hypertriglyceridemia may offer clues.[7]

Causes

- Overeating[8]

- Obesity

- Diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance - it is one of the defined components of metabolic syndrome (along with central obesity, hypertension, and hyperglycemia)

- Excess alcohol consumption

- Kidney failure, nephrotic syndrome

- Genetic predisposition; some forms of familial hyperlipidemia such as familial combined hyperlipidemia i.e. Type II hyperlipidemia

- Lipoprotein lipase deficiency - Deficiency of this water-soluble enzyme, that hydrolyzes triglycerides in lipoproteins, leads to elevated levels of triglycerides in the blood.

- Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency or Cholesteryl ester storage disease

- Certain medications e.g. isotretinoin, hydrochlorothiazide diuretics, beta blockers, protease inhibitors

- Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid)

- Lupus and associated autoimmune responses [9]

- Glycogen storage disease type 1.

- Propofol

- Certain HIV medications

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made on blood tests, often performed as part of screening. The normal triglyceride level is less than 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L).[5][8] Once diagnosed, other blood tests are usually required to determine whether the raised triglyceride level is caused by other underlying disorders ("secondary hypertriglyceridemia") or whether no such underlying cause exists ("primary hypertriglyceridaemia"). There is a hereditary predisposition to both primary and secondary hypertriglyceridemia.[5]

-

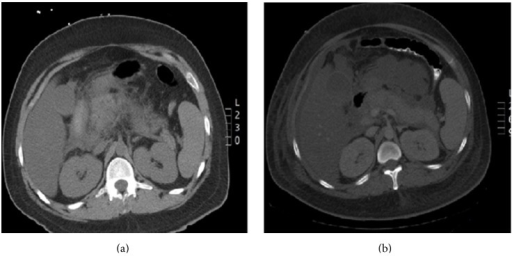

Pegaspargase induced hypertriglyceridemia a) Enlarged pancreas with peripancreatic inflammation b) Interval worsening of acute pancreatitis

-

Blood samples of a young person with extreme hypertriglyceridemia

Screening

In 2016 the United States Preventive Services Task Force concluded that testing the general population under the age of 40 without symptoms is of unclear benefit.[10][11]

Treatment

Lifestyle changes including weight loss, exercise and dietary modification may improve hypertriglyceridemia.[5][12][13] This may include restriction of carbohydrates (specifically fructose)[12] and fat in the diet and the consumption of omega-3 fatty acids from algae, nuts, and seeds.[14][15]

The decision to treat hypertriglyceridemia with medication depends on the levels and on the presence of other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Very high levels that would increase the risk of pancreatitis is treated with a drug from the fibrate class. Niacin and omega-3 fatty acids as well as drugs from the statin class may be used in conjunction, with statins being the main drug treatment for moderate hypertriglyceridemia where reduction of cardiovascular risk is required.[5] Medications are recommended in those with high levels of triglycerides that are not corrected with lifestyle modifications, with fibrates being recommended first.[5][16][17] Epanova (omega-3-carboxylic acids) is another prescription drug used to treat very high levels of blood triglycerides.[18]

Pancreatitis

In those with pancreatitis due to high triglycerides treatment is with intravenous fluids, insulin, and potentially plasmapheresis.[2][3] Insulin can be used either as an injection under the skin or into a vein.[3] Doses of 0.1 to 0.4 units per kg per hour by slow injection have been used.[3] Heparin has also be used, not for its blood thinning effect, but for its effect on an enzyme that regulates triglycerides.[3]

In those with mildly increased triglycerides the use of statins may slightly decrease the risk of pancreatitis while fibrates may slightly increase the risk.[19] Effects in severe disease have not been studied as of 2023.[19]

Epidemiology

As of 2006, the rates of hypertriglyceridemia in the United States was 30%.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "High Blood Triglycerides | NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Parhofer, KG; Laufs, U (6 December 2019). "The Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypertriglyceridemia". Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 116 (49): 825–832. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2019.0825. PMID 31888796.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Rawla, P; Sunkara, T; Thandra, KC; Gaduputi, V (December 2018). "Hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis: updated review of current treatment and preventive strategies". Clinical journal of gastroenterology. 11 (6): 441–448. doi:10.1007/s12328-018-0881-1. PMID 29923163.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Karanchi, H; Muppidi, V; Wyne, K (January 2020). "Hypertriglyceridemia". PMID 29083756.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. (September 2012). "Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97 (9): 2969–89. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213. PMC 3431581. PMID 22962670.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Yuan G, Al-Shali KZ, Hegele RA (April 2007). "Hypertriglyceridemia: its etiology, effects and treatment". CMAJ. 176 (8): 1113–20. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060963. PMC 1839776. PMID 17420495.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Tsuang W, Navaneethan U, Ruiz L, Palascak JB, Gelrud A (April 2009). "Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: presentation and management". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 104 (4): 984–91. doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.27. PMID 19293788.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Pejic RN, Lee DT (May–Jun 2006). "Hypertriglyceridemia". J Am Board Fam Med. 19 (3): 310–6. doi:10.3122/jabfm.19.3.310. PMID 16672684.

- ↑ Beigneux, Anne P.; Miyashita, Kazuya; Ploug, Michael; Blom, Dirk J.; Ai, Masumi; Linton, Macrae F.; Khovidhunkit, Weerapan; Dufour, Robert; Garg, Abhimanyu; McMahon, Maureen A.; Pullinger, Clive R.; Sandoval, Norma P.; Hu, Xuchen; Allan, Christopher M.; Larsson, Mikael; Machida, Tetsuo; Murakami, Masami; Reue, Karen; Tontonoz, Peter; Goldberg, Ira J.; Moulin, Philippe; Charrière, Sybil; Fong, Loren G.; Nakajima, Katsuyuki; Young, Stephen G. (August 27, 2017). "Autoantibodies against GPIHBP1 as a Cause of Hypertriglyceridemia". NEJM. 376 (17): 1647–1658. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1611930. PMC 5555413. PMID 28402248.

- ↑ Chou, Roger; Dana, Tracy; Blazina, Ian; Daeges, Monica; Bougatsos, Christina; Jeanne, Thomas L. (9 August 2016). "Screening for Dyslipidemia in Younger Adults: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine. 165 (8): 560–564. doi:10.7326/M16-0946. PMID 27538032.

- ↑ Bibbins-Domingo, Kirsten; Grossman, David C.; Curry, Susan J.; Davidson, Karina W.; Epling, John W.; García, Francisco A. R.; Gillman, Matthew W.; Kemper, Alex R.; Krist, Alex H.; Kurth, Ann E.; Landefeld, C. Seth; Lefevre, Michael; Mangione, Carol M.; Owens, Douglas K.; Phillips, William R.; Phipps, Maureen G.; Pignone, Michael P.; Siu, Albert L. (August 9, 2016). "Screening for Lipid Disorders in Children and Adolescents". JAMA. 316 (6): 625–33. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.9852. PMID 27532917.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Nordestgaard, BG; Varbo, A (August 2014). "Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease". The Lancet. 384 (9943): 626–635. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61177-6. PMID 25131982.

- ↑ GILL, Jason; Sara HERD; Natassa TSETSONIS; Adrianne HARDMAN (Feb 2002). "Are the reductions in triacylglycerol and insulin levels after exercise related?". Clinical Science. 102 (2): 223–231. doi:10.1042/cs20010204. PMID 11834142.

- ↑ Davidson, MH (28 January 2008). "Pharmacological Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease". In Davidson, Michael H; Toth, Peter P; Maki, Kevin C (eds.). Therapeutic Lipidology. Contemporary Cardiology. Cannon, Christopher P.; Armani, Annemarie M. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press, Inc. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-1-58829-551-4.

- ↑ Anagnostis, P; Paschou, SA; Goulis, DG; Athyros, VG; Karagiannis, A (February 2018). "Dietary management of dyslipidaemias. Is there any evidence for cardiovascular benefit?". Maturitas. 108: 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.11.011. PMID 29290214.

- ↑ Abourbih S, Filion KB, Joseph L, Schiffrin EL, Rinfret S, Poirier P, Pilote L, Genest J, Eisenberg MJ (2009). "Effect of fibrates on lipid profiles and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review". Am J Med. 122 (10): 962.e1–962.e8. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.03.030. PMID 19698935.

- ↑ Jun M, Foote C, Lv J (2010). "Effects of fibrates on cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 375 (9729): 1875–1884. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60656-3. PMID 20462635.

- ↑ Blair HA, Dhillon S (2014). "Omega-3 carboxylic acids (Epanova): a review of its use in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia". Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 14: 393–400. doi:10.1007/s40256-014-0090-3. PMID 25234378.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Ton, Joey (11 June 2023). "#342 Triglyce-Ride that High? (Free)". CFPCLearn. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |