Prenatal testing

| Prenatal testing | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Prenatal screening, Prenatal diagnosis | |

Non-invasive prenatal test analysis | |

| Purpose | detecting problems with the pregnancy |

Prenatal testing is a tool that can be used to detect some of these abnormalities at various stages prior to birth. Prenatal testing consists of prenatal screening and prenatal diagnosis, which are aspects of prenatal care that focus on detecting problems with the pregnancy as early as possible.[1] These may be anatomic and physiologic problems with the health of the zygote, embryo, or fetus, either before gestation even starts (as in preimplantation genetic diagnosis) or as early in gestation as practicable. Screening can detect problems such as neural tube defects, chromosome abnormalities, and gene mutations that would lead to genetic disorders and birth defects, such as spina bifida, cleft palate, Down syndrome, Tay–Sachs disease, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy, and fragile X syndrome. Some tests are designed to discover problems which primarily affect the health of the mother, such as PAPP-A to detect pre-eclampsia or glucose tolerance tests to diagnose gestational diabetes. Screening can also detect anatomical defects such as hydrocephalus, anencephaly, heart defects, and amniotic band syndrome.

Prenatal screening focuses on finding problems among a large population with affordable and noninvasive methods. Prenatal diagnosis focuses on pursuing additional detailed information once a particular problem has been found, and can sometimes be more invasive. The most common screening procedures are routine ultrasounds, blood tests, and blood pressure measurement. Common diagnosis procedures include amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling. In some cases, the tests are administered to determine if the fetus will be aborted, though physicians and patients also find it useful to diagnose high-risk pregnancies early so that delivery can be scheduled in a tertiary care hospital where the baby can receive appropriate care.

Prenatal testing in recent years has been moving towards non-invasive methods to determine the fetal risk for genetic disorders. The rapid advancement of modern high-performance molecular technologies along with the discovery of cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) in maternal plasma has led to new methods for the determination of fetal chromosomal aneuploidies. This type of testing is referred to as non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT). Invasive procedures remain important, though, especially for their diagnostic value in confirming positive non-invasive findings and detecting genetic disorders.[2] Birth defects have an occurrence between 1 to 6%.[3]

Purpose

There are three purposes of prenatal diagnosis: (1) to enable timely medical or surgical treatment of a condition before or after birth, (2) to give the parents the chance to abort a fetus with the diagnosed condition, and (3) to give parents the chance to prepare psychologically, socially, financially, and medically for a baby with a health problem or disability, or for the likelihood of a stillbirth. Prior information about problems in pregnancy means that healthcare staff as well as parents can better prepare themselves for the delivery of a child with a health problem. For example, Down syndrome is associated with cardiac defects that may need intervention immediately upon birth.[5]

Guidelines

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines currently recommend that anyone who is pregnant, regardless of age, should discuss and be offered non-invasive prenatal genetic screening and diagnostic testing options.[6] Non-invasive prenatal genetic screening is typically performed at the end of the 1st trimester (11–14 weeks) or during the beginning of the second trimester (15–20 weeks). This involves the pregnant woman receiving a blood draw with a needle and a syringe and an ultrasound of the fetus. Screening tests can then include serum analyte screening or cell-free fetal DNA, and nuchal translucency ultrasound [NT], respectively.[7] It is important to note that screening tests are not diagnostic, and concerning screening results should be followed up with invasive diagnostic testing for a confirmed diagnosis. Invasive diagnostic prenatal genetic testing can involve chronic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis.[8] The ACOG recommends genetic screening before pregnancy to all pregnant women planning to have a family.[9] After comprehensive counseling and discussion that acknowledges residual risks, it is important to respect the patients' right of choosing whether or not to pursue any component of genetic testing.[citation needed]

The following are some reasons why a woman might consider her risk of birth defects already to be high enough to warrant skipping screening and going straight for invasive testing:[8]

- Increased risk of fetal aneuploidy based on personal obstetric history or family history affected by aneuploidy

- Increased risk for a known genetic or biochemical disease of the fetus

- Maternal transmissible infectious disease such as rubella or toxoplasma

- Parental request in the context of acute parental anxiety or under exceptional circumstances

By invasiveness

Diagnostic prenatal testing can be performed by invasive or non-invasive methods. An invasive method involves probes or needles being inserted into the uterus, e.g. amniocentesis, which can be done from about 14 weeks gestation, and usually up to about 20 weeks, and chorionic villus sampling, which can be done earlier (between 9.5 and 12.5 weeks gestation) but which may be slightly more risky to the fetus. One study comparing transabdominal chorionic villus sampling with second trimester amniocentesis found no significant difference in the total pregnancy loss between the two procedures.[10] However, transcervical chorionic villus sampling carries a significantly higher risk, compared with a second-trimester amniocentesis, of total pregnancy loss (relative risk 1.40; 95% confidence interval 1.09 to 1.81) and spontaneous miscarriage (9.4% risk; relative risk 1.50; 95% confidence interval 1.07 to 2.11).[10]

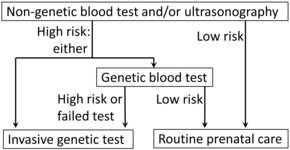

Non-invasive techniques include examinations of the woman's womb through ultrasonography and maternal serum screens (i.e. Alpha-fetoprotein). Blood tests for select trisomies (Down syndrome in the United States, Down and Edwards syndromes in China) based on detecting cell-free placental DNA present in maternal blood, also known as non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT), have become available.[11] If an elevated risk of chromosomal or genetic abnormality is indicated by a non-invasive screening test, a more invasive technique may be employed to gather more information.[12] In the case of neural tube defects, a detailed ultrasound can non-invasively provide a definitive diagnosis.[citation needed]

One of the major advantages of the non-invasive prenatal testing is that the chance of a false positive result is very low. This accuracy is very important for the pregnant woman, as due to a high sensitivity and specificity of the testing, especially for Down syndrome, the invasive testing could be avoided, which includes the risk of a miscarriage.[13][14]

| Invasiveness | Test | Comments | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive | Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) | During in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures, it is possible to sample cells from human embryos before implantation.[15] PGD is in itself non-invasive, but IVF usually involves invasive procedures such as transvaginal oocyte retrieval | before implantation |

| Non-invasive | External examination | Examination of the woman's uterus from outside the body. The uterus is commonly palpated to determine if there are problems with the position of the fetus (i.e. breech position). Fundal height may also be measured. | Second or third trimester |

| Non-invasive | Ultrasound detection | Commonly dating scans (sometimes known as booking scans or dating ultrasounds) from 7 weeks to confirm pregnancy dates and look for multiple pregnancies. The specialised nuchal scan at 11–13 weeks may be used to identify higher risks of Downs syndrome. Later morphology scans, also called anatomy ultrasound, from 18 weeks may check for any abnormal development. Additional ultrasounds may be performed if there are any other problems with the pregnancy, or if the pregnancy is post-due. | First or second trimester |

| Non-invasive | Fetal heartbeat | Listening to the fetal heartbeat via an external monitor placed on the outside of the abdomen. | First or second trimester |

| Non-invasive | Non-stress test | Use of cardiotocography during the third trimester to monitor fetal wellbeing. | Third trimester |

| Non-invasive | Maternal blood pressure | Used to screen for pre-eclampsia throughout the pregnancy. | First, second and third trimester |

| Non-invasive | Maternal weighing | Unusually low or high maternal weight can indicate problems with the pregnancy. | First, second and third trimesters. |

| Less invasive | Fetal cells in maternal blood (FCMB)[16] | Requires a maternal blood draw. Based on enrichment of fetal cells which circulate in maternal blood. Since fetal cells hold all the genetic information of the developing fetus, they can be used to perform prenatal diagnosis.[17] | First trimester |

| Less invasive | Cell-free fetal DNA in maternal blood | Requires a maternal blood draw. Based on DNA of fetal origin circulating in the maternal blood. Testing can potentially identify fetal aneuploidy[18] (available in the United States, beginning 2011) and gender of a fetus as early as six weeks into a pregnancy. Fetal DNA ranges from about 2–10% of the total DNA in maternal blood.

Cell-free fetal DNA also allows whole genome sequencing of the fetus, thus determining the complete DNA sequence of every gene.[19] |

First trimester |

| Less invasive | Glucose tolerance testing | Requires a maternal blood draw. Used to screen for gestational diabetes. | Second trimester |

| Less invasive | Transcervical retrieval of trophoblast cells | Cervical mucus aspiration, cervical swabbing, and cervical or intrauterine lavage can be used to retrieve trophoblast cells for diagnostic purposes, including prenatal genetic analysis. Success rates for retrieving fetal trophoblast cells vary from 40% to 90%.[20] It can be used for fetal sex determination and identify aneuploidies.[20] Antibody markers have proven useful to select trophoblast cells for genetic analysis and to demonstrate that the abundance of recoverable trophoblast cells diminishes in abnormal gestations, such as in ectopic pregnancy or anembryonic gestation.[20] | First trimester[20] |

| Less invasive | Maternal serum screening | Including β-hCG, PAPP-A, alpha fetoprotein, inhibin-A. | First or second trimester |

| More invasive | Chorionic villus sampling | Involves getting a sample of the chorionic villus and testing it. This can be done earlier than amniocentesis, but may have a higher risk of miscarriage, estimated at 1%. | After 10 weeks |

| More invasive | Amniocentesis | This can be done once enough amniotic fluid has developed to sample. Cells from the fetus will be floating in this fluid, and can be separated and tested. Miscarriage risk of amniocentesis is commonly quoted as 0.06% (1:1600).[21] By amniocentesis it is also possible to cryopreserve amniotic stem cells.[22][23][24] | After 15 weeks |

| More invasive | Embryoscopy and fetoscopy | Though rarely done, these involve putting a probe into a women's uterus to observe (with a video camera), or to sample blood or tissue from the embryo or fetus. | |

| More invasive | Percutaneous umbilical cord blood sampling | PUBS is a diagnostic genetic test that examines blood from the fetal umbilical cord to detect fetal abnormalities. | 24–34 weeks |

By stage

Pre-conception

Prior to conception, couples may elect to have genetic testing done to determine the odds of conceiving a child with a known genetic anomaly. The most common in the Caucasian population are:[citation needed]

- Cystic fibrosis

- Fragile X syndrome

- Blood disorders such as sickle cell disease

- Tay-Sachs disease

- Spinal muscular atrophy

Hundreds of additional conditions are known and more discovered on a regular basis. However the economic justification for population-wide testing of all known conditions is not well supported, particularly once the cost of possible false positive results and concomitant follow-up testing are taken into account.[25] There are also ethical concerns related to this or any type of genetic testing.[citation needed]

One or both partners may be aware of other family members with these diseases. Testing prior to conception may alleviate concern, prepare the couple for the potential short- or long-term consequences of having a child with the disease, direct the couple toward adoption or foster parenting, or prompt for preimplantation genetic testing during in vitro fertilization. If a genetic disorder is found, professional genetic counseling is usually recommended owing to the host of ethical considerations related to subsequent decisions for the partners and potential impact on their extended families. Most, but not all, of these diseases follow Mendelian inheritance patterns. Fragile X syndrome is related to expansion of certain repeated DNA segments and may change generation-to-generation.[citation needed]

First trimester

At early presentation of pregnancy at around 6 weeks, early dating ultrasound scan may be offered to help confirm the gestational age of the embryo and check for a single or twin pregnancy, but such a scan is unable to detect common abnormalities. Details of prenatal screening and testing options may be provided.[citation needed]

Around weeks 11–13, nuchal translucency scan (NT) may be offered which can be combined with blood tests for PAPP-A and beta-hCG, two serum markers that correlate with chromosomal abnormalities, in what is called the First Trimester Combined Test. The results of the blood test are then combined with the NT ultrasound measurements, maternal age, and gestational age of the fetus to yield a risk score for Down syndrome, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13. First Trimester Combined Test has a sensitivity (i.e. detection rate for abnormalities) of 82–87% and a false-positive rate of around 5%.[26][27]

Cell-free fetal DNA is also available during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Second trimester

The anomaly scan is performed between 18 and 22 weeks of gestational age. The International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG) recommends that this ultrasound is performed as a matter of routine prenatal care, to measure the fetus so that growth abnormalities can be recognized quickly later in pregnancy, and to assess for congenital malformations and multiple pregnancies (i.e. twins).[28] The scan can detect anencephaly, open spina bifida, cleft lip, diaphragmatic hernia, gastroschisis, omphalocele, congenital heart defect, bilateral renal agenesis, osteochondrodysplasia, Edwards syndrome, and Patau syndrome.[29]

A second-trimester Quad blood test may be taken (the Triple test is widely considered obsolete but in some states, such as Missouri, where Medicaid only covers the Triple test, that's what the patient typically gets). With integrated screening, both a First Trimester Combined Test and a Triple/Quad test is performed, and a report is only produced after both tests have been analyzed. However patients may not wish to wait between these two sets of tests. With sequential screening, a first report is produced after the first trimester sample has been submitted, and a final report after the second sample. With contingent screening, patients at very high or very low risks will get reports after the first-trimester sample has been submitted. Only patients with moderate risk (risk score between 1:50 and 1:2000) will be asked to submit a second-trimester sample, after which they will receive a report combining information from both serum samples and the NT measurement. The First Trimester Combined Test and the Triple/Quad test together have a sensitivity of 88–95% with a 5% false-positive rate for Down syndrome, though they can also be analyzed in such a way as to offer a 90% sensitivity with a 2% false-positive rate. Finally, patients who do not receive an NT ultrasound in the 1st trimester may still receive a Serum Integrated test involving measuring PAPP-A serum levels in the 1st trimester and then doing a Quad test in the 2nd trimester. This offers an 85–88% sensitivity and 5% false-positive rate for Down syndrome. Also, a patient may skip the 1st-trimester screening entirely and receive only a 2nd-trimester Quad test, with an 81% sensitivity for Down syndrome and 5% false-positive rate.[30]

Third trimester

Third-trimester prenatal testing generally focuses on maternal wellbeing and reducing fetal morbidity/mortality. Group B streptococcal infection (also called Group B strep) may be offered, which is a major cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality. Group B strep is an infection that may be passed to an infant during birth. Vaginal screening for GBS is performed between 34 and 37 weeks of gestational age, so that mothers that are positive for the bacterium can receive treatment before delivery. During the third trimester, some institutions may require evaluations of hemoglobin/hematocrit, syphilis serology, and HIV screening. Also, before delivery, an assessment of fetal position and estimated fetal weight is documented.[31]

Maternal serum screening

First-trimester maternal serum screening can check levels of free β-hCG, PAPP-A, intact or beta hCG, or h-hCG in the woman's serum, and combine these with the measurement of nuchal translucency (NT). Some institutions also look for the presence of a fetal nasalbone on the ultrasound.

Second-trimester maternal serum screening (AFP screening, triple screen, quad screen, or penta screen) can check levels of alpha fetoprotein, β-hCG, inhibin-A, estriol, and h-hCG (hyperglycosolated hCG) in the woman's serum.

The triple test measures serum levels of AFP, estriol, and beta-hCG, with a 70% sensitivity and 5% false-positive rate. It is complemented in some regions of the United States, as the Quad test (adding inhibin A to the panel, resulting in an 81% sensitivity and 5% false-positive rate for detecting Down syndrome when taken at 15–18 weeks of gestational age).[32]

The biomarkers PAPP-A and β-hCG seem to be altered for pregnancies resulting from ICSI, causing a higher false-positive rate. Correction factors have been developed and should be used when screening for Down's syndrome in singleton pregnancies after ICSI,[33] but in twin pregnancies such correction factors have not been fully elucidated.[33] In vanishing twin pregnancies with a second gestational sac with a dead fetus, first-trimester screening should be based solely on the maternal age and the nuchal translucency scan as biomarkers are altered in these cases.[33]

Advances in prenatal screening

Measurement of fetal proteins in maternal serum is a part of standard prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy and neural tube defects.[34][35] Computational predictive model shows that extensive and diverse feto-maternal protein trafficking occurs during pregnancy and can be readily detected non-invasively in maternal whole blood.[36] This computational approach circumvented a major limitation, the abundance of maternal proteins interfering with the detection of fetal proteins, to fetal proteomic analysis of maternal blood. Entering fetal gene transcripts previously identified in maternal whole blood into a computational predictive model helped develop a comprehensive proteomic network of the term neonate. It also shows that the fetal proteins detected in pregnant woman's blood originate from a diverse group of tissues and organs from the developing fetus. Development proteomic networks dominate the functional characterization of the predicted proteins, illustrating the potential clinical application of this technology as a way to monitor normal and abnormal fetal development.

The difference in methylation of specific DNA sequences between mother and fetus can be used to identify fetal-specific DNA in the blood circulation of the mother. In a study published in the March 6, 2011, online issue of Nature, using this non-invasive technique a group of investigators from Greece and UK achieved correct diagnosis of 14 trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) and 26 normal cases.[37][38] Using massive parallel sequencing, a study testing for trisomy 21 only, successfully detected 209 of 212 cases (98.6%) with 3 false-positives in 1,471 pregnancies (0.2%).[11] With commercially available non-invasive (blood) testing for Down syndrome having become available to patients in the United States and already available in China, in October 2011, the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis created some guidance. Based on its sensitivity and specificity, it constitutes an advanced screening test and that positive results require confirmation by an invasive test, and that while effective in the diagnosis of Down syndrome, it cannot assess half the abnormalities detected by invasive testing. The test is not recommended for general use until results from broader studies have been reported, but may be useful in high-risk patients in conjunction with genetic counseling.[12]

A study in 2012 found that the maternal plasma cell-free DNA test was also able to detect trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) in 100% of the cases (59/59) at a false-positive rate of 0.28%, and trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome) in 91.7% of the cases (11/12) at a false-positive rate of 0.97%. The test interpreted 99.1% of samples (1,971/1,988); among the 17 samples without an interpretation, three were trisomy 18. The study stated that if z-score cutoffs for trisomy 18 and 13 were raised slightly, the overall false-positive rates for the three aneuploidies could be as low as 0.1% (2/1,688) at an overall detection rate of 98.9% (280/283) for common aneuploidies (this includes all three trisomies: Down, Edwards and Patau).[39]

Screening for chromosomal abnormalities

The goal of prenatal genetic testing is to identify pregnancies at high risk of abnormalities, allowing for early intervention, termination or appropriate management and preparation measures.[40]

Ultrasound and serum markers

Ultrasound imaging provides the opportunity to conduct a nuchal translucency (NT) scan screening for chromosomal abnormalities such as Down syndrome (trisomy 21), Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18), and Patau syndrome (trisomy 13). Using the information from the NT scan the mother can be offered an invasive diagnostic test for fetal chromosomal abnormalities. Serum markers are utilized in a similar fashion to identify gestations that should be recommended for further testing. When the NT scan or serum markers arouse suspicion for chromosomal abnormalities the following genetic tests may be conducted on fetal or placental tissue samples: Interphase-fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), quantitative PCR and direct preparation of chromosomes from chorionic villi.[41]

Fetal cell-free DNA

Fetal cell-free DNA testing allows for the detection of apoptotic fetal cells and fetal DNA circulating in maternal blood for the noninvasive diagnosis of fetal aneuploidy.[41][42] A meta-analysis that investigated the success rate of using fetal cell-free DNA from maternal blood to screen for aneuploidies found that this technique detected trisomy 13 in 99% of the cases, trisomy 18 in 98% of the cases and trisomy 21 in 99% of the cases.[42][43] Failed tests using fetal cell-free DNA are more likely to occur in fetuses with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18 but not with trisomy 21.[44] Previous studies found elevated levels of cell-free fetal DNA for trisomy 13 and 21 from maternal serum when compared to women with euploid pregnancies.[45][46][47][48] However, an elevation of cell-free DNA for trisomy 18 was not observed.[45] Circulating fetal nucleated cells comprise only three to six percent of maternal blood plasma DNA, reducing the detection rate of fetal developmental abnormalities.[48] Two alternative approaches have been developed for the detection of fetal aneuploidy. The first involves the measuring of the allelic ratio of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the mRNA coding region in the placenta. The next approach is analyzing both maternal and fetal DNA and looking for differences in the DNA methylation patterns.[48]

Digital PCR

Recently, it has been proposed that digital PCR analysis can be conducted on fetal cell-free DNA for detection of fetal aneuploidy. Research has shown that digital PCR can be used to differentiate between normal and aneuploid DNA.[49]

A variation of the PCR technique called multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), targeting DNA, has been successively applied for diagnosing fetal aneuploidy as a chromosome- or gene-specific assay.[50]

Shotgun sequencing

Fetal cell-free DNA has been directly sequenced using shotgun sequencing technology. In one study, DNA was obtained from the blood plasma of eighteen pregnant women. This was followed by mapping the chromosome using the quantification of fragments. This was done using advanced methods in DNA sequencing resulting in the parallel sequencing of the fetal DNA. The amount of sequence tags mapped to each chromosome was counted. If there was a surplus or deficiency in any of the chromosomes, this meant that there was a fetal aneuploid. Using this method of shotgun sequencing, the successful identification of trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), trisomy 18 (Edward syndrome), and trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome) was possible. This method of noninvasive diagnosis is now starting to be heavily used and researched further.[18]

Other techniques

Fetal components in samples from maternal blood plasma can be analyzed by genome-wide techniques not only by total DNA, but also by methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (with tiling array), microRNA (such as with Megaplex) and total RNA (RNA-sequencing).[50]

Patient acceptance

Research was conducted to determine how women felt about noninvasive diagnosis of fetal aneuploid using maternal blood. This study was conducted using surveys. It was reported that eighty-two percent of pregnant women and seventy-nine percent of female medical students view this type of diagnosis in a positive light, agreeing that it is important for prenatal care. Overall, women responded optimistically that this form of diagnosis will be available in the future.[51]

Ethical and practical issues

Non-genetic prenatal testing

Parents need to make informed decisions about screening, diagnosis, and any actions to be taken as a result. Many screening tests are inaccurate, so one worrisome test result frequently leads to additional, more invasive tests. If prenatal testing confirms a serious disability, many parents are forced to decide whether to continue the pregnancy or seek an abortion. The "option" of screening becomes an unexpected requirement to decide. See wrongful abortion.

In some genetic conditions, for instance cystic fibrosis, an abnormality can only be detected if DNA is obtained from the fetus. Usually an invasive method is needed to do this.[citation needed]

Ultrasound of a fetus, which is considered a screening test, can sometimes miss subtle abnormalities. For example, studies show that a detailed 2nd-trimester ultrasound, also called a level 2 ultrasound, can detect about 97% of neural tube defects such as spina bifida[citation needed]. Ultrasound results may also show "soft signs," such as an Echogenic intracardiac focus or a Choroid plexus cyst, which are usually normal, but can be associated with an increased risk for chromosome abnormalities.

Other screening tests, such as the Quad test, can also have false positives and false negatives. Even when the Quad results are positive (or, to be more precise, when the Quad test yields a score that shows at least a 1 in 270 risk of abnormality), usually the pregnancy is normal, but additional diagnostic tests are offered. In fact, consider that Down syndrome affects about 1:400 pregnancies; if you screened 4000 pregnancies with a Quad test, there would probably be 10 Down syndrome pregnancies of which the Quad test, with its 80% sensitivity, would call 8 of them high-risk. The quad test would also tell 5% (~200) of the 3990 normal women that they are high-risk. Therefore, about 208 women would be told they are high-risk, but when they undergo an invasive test, only 8 (or 4% of the high risk pool) will be confirmed as positive and 200 (96%) will be told that their pregnancies are normal. Since amniocentesis has approximately a 0.5% chance of miscarriage, one of those 200 normal pregnancies might result in a miscarriage because of the invasive procedure. Meanwhile, of the 3792 women told they are low-risk by the Quad test, 2 of them will go on to deliver a baby with Down syndrome. The Quad test is therefore said to have a 4% positive predictive value (PPV) because only 4% of women who are told they are "high-risk" by the screening test actually have an affected fetus. The other 96% of the women who are told they are "high-risk" find out that their pregnancy is normal.[citation needed]

By comparison, in the same 4000 women, a screening test that has a 99% sensitivity and a 0.5% false positive rate would detect all 10 positives while telling 20 normal women that they are positive. Therefore, 30 women would undergo a confirmatory invasive procedure and 10 of them (33%) would be confirmed as positive and 20 would be told that they have a normal pregnancy. Of the 3970 women told by the screen that they are negative, none of the women would have an affected pregnancy. Therefore, such a screen would have a 33% positive predictive value.

The real-world false-positive rate for the Quad test (as well as 1st Trimester Combined, Integrated, etc.) is greater than 5%. 5% was the rate quoted in the large clinical studies that were done by the best researchers and physicians, where all the ultrasounds were done by well-trained sonographers and the gestational age of the fetus was calculated as closely as possible. In the real world, where calculating gestational age may be a less precise art, the formulas that generate a patient's risk score are not as accurate and the false-positive rate can be higher, even 10%.

Because of the low accuracy of conventional screening tests, 5–10% of women, often those who are older, will opt for an invasive test even if they received a low-risk score from the screening. A patient who received a 1:330 risk score, while technically low-risk (since the cutoff for high-risk is commonly quoted as 1:270), might be more likely to still opt for a confirmatory invasive test. On the other hand, a patient who receives a 1:1000 risk score is more likely to feel assuaged that her pregnancy is normal.

Both false positives and false negatives will have a large impact on a couple when they are told the result, or when the child is born. Diagnostic tests, such as amniocentesis, are considered to be very accurate for the defects they check for, though even these tests are not perfect, with a reported 0.2% error rate (often due to rare abnormalities such as mosaic Down syndrome where only some of the fetal/placental cells carry the genetic abnormality).

A higher maternal serum AFP level indicates a greater risk for anencephaly and open spina bifida. This screening is 80% and 90% sensitive for spina bifida and anencephaly, respectively.[citation needed]

Amniotic fluid acetylcholinesterase and AFP level are more sensitive and specific than AFP in predicting neural tube defects.

Many maternal-fetal specialists do not bother to even do an AFP test on their patients because they do a detail ultrasound on all of them in the 2nd trimester, which has a 97% detection rate for neural tube defects such as anencephaly and open spina bifida. Performing tests to determine possible birth defects is mandatory in all U.S. states.[citation needed] Failure to detect issues early can have dangerous consequences on both the mother and the baby. OBGYNs may be held culpable. In one case a man who was born with spina bifida was awarded $2 million in settlement, apart from medical expenses, due to the OBGYN's negligence in conducting AFP tests.[52]

No prenatal test can detect all forms of birth defects and abnormalities.

Prenatal genetic testing

Another important issue is the uncertainty of prenatal genetic testing. Uncertainty on genetic testing results from several reasons: the genetic test is associated with a disease but the prognosis and/or probability is unknown, the genetic test provides information different than the familiar disease they tested for, found genetic variants have unknown significance, and finally, results may not be associated with found fetal abnormalities.[53] Richardson and Ormond thoroughly addressed the issue of uncertainty of genetic testing and explained its implication for bioethics. First, the principle of beneficence is assumed in prenatal testing by decreasing the risk of miscarriage, however, uncertain information derived from genetic testing may harm the parents by provoking anxiety and leading to the termination of a fetus that is probably healthy. Second, the principle of autonomy is undermined given a lack of comprehension resulting from new technologies and changing knowledge in the field of genetics. And third, the principle of justice raised issues regarding equal access to emerging prenatal tests.

Availability of treatments

If a genetic disease is detected, there is often no treatment that can help the fetus until it is born. However, in the US, there are prenatal surgeries for spina bifida fetus.[citation needed] Early diagnosis gives the parents time to research and discuss post-natal treatment and care, or in some cases, abortion. Genetic counselors are usually called upon to help families make informed decisions regarding results of prenatal diagnosis.

Patient education

Researchers have studied how disclosing amniocentesis or chorionic villous sampling (CVS) results on a fixed date versus a variable date (i.e. "when available") affects maternal anxiety. Systematic review of the relevant articles found no conclusive evidence to support issuing amniocentesis results as soon as they become available (in comparison to issuing results on a pre-defined fixed date). The researchers concluded that further studies evaluating the effect of different strategies for disclosing CVS results on maternal anxiety are needed.[54]

Disability rights

Disability rights activists and scholars have suggested a more critical view of prenatal testing and its implications for people with disabilities. They argue that there is pressure to abort fetuses that might be born with disabilities, and that these pressures rely on eugenics interests and ableist stereotypes.[55] This selective abortion relies on the ideas that people with disabilities cannot live desirable lives, that they are "defective," and that they are burdens, while disability scholars argue that "oppression is what's most disabling about disability." Marsha Saxton suggests that women should question whether or not they are relying on real, factual information about people with disabilities or on stereotypes if they decide to abort a fetus with a disability.[56]

Societal pressures

Amniocentesis has become the standard of care for prenatal care visits for women who are "at risk" or over a certain age. The wide use of amniocentesis has been defined as consumeristic.[57] and some argue that this can be in conflict with the right to privacy,[58] Most obstetricians (depending on the country) offer patients the AFP triple test, HIV test, and ultrasounds routinely. However, almost all women meet with a genetic counselor before deciding whether to have prenatal diagnosis. It is the role of the genetic counselor to accurately inform women of the risks and benefits of prenatal diagnosis. Genetic counselors are trained to be non-directive and to support the patient's decision. Some doctors do advise women to have certain prenatal tests and the patient's partner may also influence the woman's decision.[citation needed]

Legal

August in 2023 Iranian government banned import and manufacture of tests kits required for first screening trimester tests, it will plague the population according to society of medicine in genetic انجمن ژنتیک پزشکی ایران.[59] Iranian state welfare organization had a genetics condition program since 1997.[60]

See also

- Amniocentesis

- Amniotic stem cell bank

- Amniotic stem cells

- Chorionic villi

- Genetic counseling

- Newborn screening

Notes and references

- ↑ "Prenatal Testing". MedlinePlus.

- ↑ Pös, Ondrej; Budiš, Jaroslav; Szemes, Tomáš (2019). "Recent trends in prenatal genetic screening and testing". F1000Research. 8: 764. doi:10.12688/f1000research.16837.1. ISSN 2046-1402. PMC 6545823. PMID 31214330.

- ↑ Outcomes, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth; Bale, Judith R.; Stoll, Barbara J.; Lucas, Adetokunbo O. (2003), "Impact and Patterns of Occurrence", Reducing Birth Defects: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World, National Academies Press (US), archived from the original on January 30, 2023, retrieved October 1, 2023

- ↑ Diagram by Mikael Häggström, MD, using following source: Jacquelyn V Halliday, MSGeralyn M Messerlian, PhDGlenn E Palomaki, PhD. "Patient education: Should I have a screening test for Down syndrome during pregnancy? (Beyond the Basics)". UpToDate.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This topic last updated: Feb 16, 2023. - ↑ Versacci P, Di Carlo D, Digilio MC, Marino B (October 2018). "Cardiovascular disease in Down syndrome". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 30 (5): 616–622. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000661. PMID 30015688. S2CID 51663233. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ "Current ACOG Guidance". www.acog.org. Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ↑ Gordon, Shaina; Langaker, Michelle D. (2022), "Prenatal Genetic Screening", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32491634, archived from the original on October 20, 2023, retrieved September 19, 2022

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ghi, T.; Sotiriadis, A.; Calda, P.; Da Silva Costa, F.; Raine-Fenning, N.; Alfirevic, Z.; McGillivray, G.; International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG) (August 2016). "ISUOG Practice Guidelines: invasive procedures for prenatal diagnosis: ISUOG Guidelines". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 48 (2): 256–268. doi:10.1002/uog.15945. PMID 27485589. S2CID 35587941.

- ↑ "Committee Opinion No. 690 Summary: Carrier Screening in the Age of Genomic Medicine". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 129 (3): 595–596. March 2017. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001947. PMID 28225420. S2CID 205468921. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis (Review). By Alfirevic Z, Mujezinovic F, Sundberg K at The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, Haddow JE, Neveux LM, Ehrich M, et al. (November 2011). "DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: an international clinical validation study". Genetics in Medicine. 13 (11): 913–20. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182368a0e. PMID 22005709. S2CID 24761833.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Benn P, Borrell A, Cuckle H, Dugoff L, Gross S, Johnson J, Maymon R, Odibo A, Schielen P, Spencer K, Wright D, Yaron Y (October 24, 2011), "Prenatal Detection of Down Syndrome using Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS): a rapid response statement from a committee on behalf of the Board of the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis" (PDF), ISPD rapid response statement, Charlottesville, VA: International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis, archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2012, retrieved October 25, 2011

- ↑ Taylor-Phillips, Sian; Freeman, Karoline; Geppert, Julia; Agbebiyi, Adeola; Uthman, Olalekan A.; Madan, Jason; Clarke, Angus; Quenby, Siobhan; Clarke, Aileen (January 1, 2016). "Accuracy of non-invasive prenatal testing using cell-free DNA for detection of Down, Edwards and Patau syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ Open. 6 (1): e010002. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010002. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 4735304. PMID 26781507. Archived from the original on May 21, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ Allyse, Megan; Minear, Mollie A; Berson, Elisa; Sridhar, Shilpa; Rote, Margaret; Hung, Anthony; Chandrasekharan, Subhashini (January 16, 2015). "Non-invasive prenatal testing: a review of international implementation and challenges". International Journal of Women's Health. 7: 113–126. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S67124. ISSN 1179-1411. PMC 4303457. PMID 25653560.

- ↑ Santiago Munne Archived January 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, INCIID – accessed July 18, 2009

- ↑ Wachtel SS, Shulman LP, Sammons D (February 2001). "Fetal cells in maternal blood". Clinical Genetics. 59 (2): 74–9. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.590202.x. PMID 11260204. S2CID 10998402.

- ↑ Herzenberg LA, Bianchi DW, Schröder J, Cann HM, Iverson GM (March 1979). "Fetal cells in the blood of pregnant women: detection and enrichment by fluorescence-activated cell sorting". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 76 (3): 1453–5. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76.1453H. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.3.1453. PMC 383270. PMID 286330.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Fan HC, Blumenfeld YJ, Chitkara U, Hudgins L, Quake SR (October 2008). "Noninvasive diagnosis of fetal aneuploidy by shotgun sequencing DNA from maternal blood". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (42): 16266–71. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10516266F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808319105. PMC 2562413. PMID 18838674.

- ↑ Yurkiewicz IR, Korf BR, Lehmann LS (January 2014). "Prenatal whole-genome sequencing--is the quest to know a fetus's future ethical?". The New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (3): 195–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1215536. PMID 24428465. S2CID 205109276. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Imudia AN, Kumar S, Diamond MP, DeCherney AH, Armant DR (April 2010). "Transcervical retrieval of fetal cells in the practice of modern medicine: a review of the current literature and future direction". Fertility and Sterility. 93 (6): 1725–30. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.11.022. PMC 2847626. PMID 20056202.

- ↑ Wilson RD, Langlois S, Johnson JA (July 2007). "Mid-trimester amniocentesis fetal loss rate" (PDF). Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 29 (7): 586–590. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32501-4. PMID 17623573. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ↑ "European Biotech Company Biocell Center Opens First U.S. Facility for Preservation of Amniotic Stem Cells in Medford, Massachusetts | Reuters". October 22, 2009. Archived from the original on October 30, 2009. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ↑ "Europe's Biocell Center opens Medford office – Daily Business Update – The Boston Globe". October 22, 2009. Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ↑ "The Ticker". Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ↑ Henneman L, Borry P, Chokoshvili D, Cornel MC, van El CG, Forzano F, et al. (June 2016). "Responsible implementation of expanded carrier screening". European Journal of Human Genetics. 24 (6): e1–e12. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.271. PMC 4867464. PMID 26980105.

- ↑ Carlson, Laura M.; Vora, Neeta L. (2017). "Prenatal Diagnosis". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 44 (2): 245–256. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ISSN 0889-8545. PMC 5548328. PMID 28499534.

- ↑ Malone, Fergal D.; Canick, Jacob A.; Ball, Robert H.; Nyberg, David A.; Comstock, Christine H.; Bukowski, Radek; Berkowitz, Richard L.; Gross, Susan J.; Dugoff, Lorraine; Craigo, Sabrina D.; Timor-Tritsch, Ilan E. (November 10, 2005). "First-trimester or second-trimester screening, or both, for Down's syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (19): 2001–2011. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043693. ISSN 1533-4406. PMID 16282175.

- ↑ Salomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Berghella V, Bilardo C, Hernandez-Andrade E, Johnsen SL, et al. (January 2011). "Practice guidelines for performance of the routine mid-trimester fetal ultrasound scan". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 37 (1): 116–26. doi:10.1002/uog.8831. PMID 20842655. S2CID 10676445.

- ↑ NHS Choices. "Mid-pregnancy anomaly scan - Pregnancy and baby - NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ↑ The California Prenatal Screening Program. cdph.ca.gov

- ↑ Kitchen, Felisha L.; Jack, Brian W. (2021), "Prenatal Screening", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29261924, archived from the original on April 16, 2022, retrieved June 26, 2021

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived October 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived October 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Lao MR, Calhoun BC, Bracero LA, Wang Y, Seybold DJ, Broce M, Hatjis CG (2009). "The ability of the quadruple test to predict adverse perinatal outcomes in a high-risk obstetric population". Journal of Medical Screening. 16 (2): 55–9. doi:10.1258/jms.2009.009017. PMID 19564516. S2CID 23214929. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Gjerris AC, Tabor A, Loft A, Christiansen M, Pinborg A (July 2012). "First trimester prenatal screening among women pregnant after IVF/ICSI". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (4): 350–9. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms010. PMID 22523111.

- ↑ Ball RH, Caughey AB, Malone FD, Nyberg DA, Comstock CH, Saade GR, et al. (July 2007). "First- and second-trimester evaluation of risk for Down syndrome". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 110 (1): 10–7. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000263470.89007.e3. PMID 17601890. S2CID 10885982. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ Dashe JS, Twickler DM, Santos-Ramos R, McIntire DD, Ramus RM (December 2006). "Alpha-fetoprotein detection of neural tube defects and the impact of standard ultrasound" (PDF). American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 195 (6): 1623–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.097. PMID 16769022. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ Maron JL, Alterovitz G, Ramoni M, Johnson KL, Bianchi DW (December 2009). "High-throughput discovery and characterization of fetal protein trafficking in the blood of pregnant women". Proteomics. Clinical Applications. 3 (12): 1389–96. doi:10.1002/prca.200900109. PMC 2825712. PMID 20186258.

- ↑ Papageorgiou EA, Karagrigoriou A, Tsaliki E, Velissariou V, Carter NP, Patsalis PC (April 2011). "Fetal-specific DNA methylation ratio permits noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 21". Nature Medicine. 17 (4): 510–3. doi:10.1038/nm.2312. PMC 3977039. PMID 21378977.

- ↑ "A New Non-invasive Test for Down Syndrome:Trisomy 21 Diagnosis using Fetal-Specific DNA Methylation". SciGuru.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ↑ Palomaki GE, Deciu C, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, Haddow JE, Neveux LM, et al. (March 2012). "DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as Down syndrome: an international collaborative study". Genetics in Medicine. 14 (3): 296–305. doi:10.1038/gim.2011.73. PMC 3938175. PMID 22281937.

- ↑ Jelin, Angie C.; Sagaser, Katelynn G.; Wilkins-Haug, Louise (April 1, 2019). "Prenatal Genetic Testing Options". Pediatric Clinics of North America. Current Advances in Neonatal Care. 66 (2): 281–293. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2018.12.016. ISSN 0031-3955. PMID 30819336. S2CID 73470036.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Miny P, Tercanli S, Holzgreve W (April 2002). "Developments in laboratory techniques for prenatal diagnosis". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 14 (2): 161–8. doi:10.1097/00001703-200204000-00010. PMID 11914694. S2CID 40591216.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Taglauer ES, Wilkins-Haug L, Bianchi DW (February 2014). "Review: cell-free fetal DNA in the maternal circulation as an indication of placental health and disease". Placenta. 35 Suppl (Suppl): S64-8. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2013.11.014. PMC 4886648. PMID 24388429.

- ↑ Gil, M. M.; Galeva, S.; Jani, J.; Konstantinidou, L.; Akolekar, R.; Plana, M. N.; Nicolaides, K. H. (June 2019). "Screening for trisomies by cfDNA testing of maternal blood in twin pregnancy: update of The Fetal Medicine Foundation results and meta-analysis". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 53 (6): 734–742. doi:10.1002/uog.20284. ISSN 1469-0705. PMID 31165549.

- ↑ Revello R, Sarno L, Ispas A, Akolekar R, Nicolaides KH (June 2016). "Screening for trisomies by cell-free DNA testing of maternal blood: consequences of a failed result". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 47 (6): 698–704. doi:10.1002/uog.15851. PMID 26743020.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Wataganara, T; LeShane, ES; et al. (2003). "Maternal serum cell-free fetal DNA levels are increased in cases of trisomy 13 but not trisomy 18. - PubMed - NCBI". Human Genetics. 112 (2): 204–8. doi:10.1007/s00439-002-0853-9. PMID 12522563. S2CID 9721963. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ Lee T, LeShane ES, Messerlian GM, Canick JA, Farina A, Heber WW, Bianchi DW (November 2002). "Down syndrome and cell-free fetal DNA in archived maternal serum". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 187 (5): 1217–21. doi:10.1067/mob.2002.127462. PMID 12439507. S2CID 31311811. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ Lo YM, Lau TK, Zhang J, Leung TN, Chang AM, Hjelm NM, et al. (October 1999). "Increased fetal DNA concentrations in the plasma of pregnant women carrying fetuses with trisomy 21". Clinical Chemistry. 45 (10): 1747–51. doi:10.1093/clinchem/45.10.1747. PMID 10508120.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Lo YM (January 2009). "Noninvasive prenatal detection of fetal chromosomal aneuploidies by maternal plasma nucleic acid analysis: a review of the current state of the art". BJOG. 116 (2): 152–7. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02010.x. PMID 19076946. S2CID 6946087.

- ↑ Zimmermann BG, Grill S, Holzgreve W, Zhong XY, Jackson LG, Hahn S (December 2008). "Digital PCR: a powerful new tool for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis?". Prenatal Diagnosis. 28 (12): 1087–93. doi:10.1002/pd.2150. PMID 19003785. S2CID 2909830.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Go AT, van Vugt JM, Oudejans CB (2010). "Non-invasive aneuploidy detection using free fetal DNA and RNA in maternal plasma: recent progress and future possibilities". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (3): 372–82. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq054. PMID 21076134.

- ↑ Kooij L, Tymstra T, van den Berg P (February 2009). "The attitude of women toward current and future possibilities of diagnostic testing in maternal blood using fetal DNA". Prenatal Diagnosis. 29 (2): 164–8. doi:10.1002/pd.2205. hdl:11370/37f11789-ccb4-42c7-aefb-60add0f166d5. PMID 19180577. S2CID 7927318. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ "Medical malpractice: Childbirth, failed to perform AFP test" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ Richardson A, Ormond KE (February 2018). "Ethical considerations in prenatal testing: Genomic testing and medical uncertainty". Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 23 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2017.10.001. PMID 29033309.

- ↑ Mujezinovic F, Prosnik A, Alfirevic Z (November 2010). "Different communication strategies for disclosing results of diagnostic prenatal testing". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD007750. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007750.pub2. PMID 21069696.

- ↑ Rubeis G, Steger F (January 2019). "A burden from birth? Non-invasive prenatal testing and the stigmatization of people with disabilities". Bioethics. 33 (1): 91–97. doi:10.1111/bioe.12518. PMID 30461042.

- ↑ Saxton, Marsha. "Disability Rights and Selective Abortion." The Reproductive Rights Reader. Nancy Ehrenreich, Ed. New York City, 2008.

- ↑ Henn W (December 2000). "Consumerism in prenatal diagnosis: a challenge for ethical guidelines". Journal of Medical Ethics. 26 (6): 444–6. doi:10.1136/jme.26.6.444. PMC 1733311. PMID 11129845.

- ↑ Botkin JR. Fetal privacy and confidentiality. Hastings Cent Rep. 1995 Sep–Oct;25(5):32–9

- ↑ "انجمن ژنتیک پزشکی: دولت مجوز تولید و واردات کیت غربالگری سهماهه اول بارداری را متوقف کرد". ایران اینترنشنال. August 16, 2023. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

- Our Bodies Ourselves chapter on Prenatal Testing and Disability Rights

- Prenatal Tests and Why Are They Important? Archived October 13, 2022, at the Wayback Machine - March Of Dimes

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1: long volume value

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- Use mdy dates from September 2021

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2017

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2010

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2011

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2007

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2021

- Obstetrical procedures

- Tests during pregnancy

- Midwifery