Glutaric acidemia type 2

| Glutaric acidemia type 2 | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MADD)[1] | |

| |

| Glutaric acid | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Glutaric acidemia type 2 is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder that is characterised by defects in the ability of the body to use proteins and fats for energy. Incompletely processed proteins and fats can build up, leading to a dangerous chemical imbalance called acidosis.

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation of this condition is as follows:[2]

- Muscle ache

- Abnormally shaped ears

- Areflexia

- Cardiac failure

- Depressed nasal bridge

- Dysphagia

Cause

Mutations in the ETFA, ETFB, and ETFDH genes cause glutaric acidemia type II. Mutations in these genes result in a deficiency in one of two enzymes that normally work together in the mitochondria, which are the energy-producing centers of cells. The ETFA and ETFB genes encode two subunits of the enzyme electron transfer flavoprotein, while the ETFDH gene encodes the enzyme electron transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase. When one of these enzymes is defective or missing, the mitochondria cannot function normally, partially broken-down proteins and fats accumulate in the cells and damage them; this damage leads to the signs and symptoms of glutaric acidemia type II.[1]

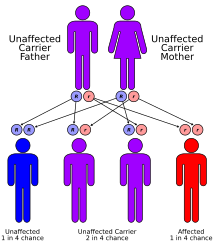

This condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means the defective gene is located on an autosome, and two copies of the gene – one from each parent – are needed to inherit the disorder. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive disorder are carriers of one copy of the defective gene, but do not show signs and symptoms of the disorder themselves.[citation needed]

-

Heart of the 6-day-old GAII person with a causative novel ETFB mutation showing a thickened ventricle wall and narrow ventricular lumen.

-

Glutaric acidemia type 2 has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance.

Diagnosis

Glutaric acidemia type 2 often appears in infancy as a sudden metabolic crisis, in which acidosis and low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) cause weakness, behavior changes, and vomiting. There may also be enlargement of the liver, heart failure, and a characteristic odor resembling that of sweaty feet. Some infants with glutaric acidemia type 2 have birth defects, including multiple fluid-filled growths in the kidneys (polycystic kidneys). Glutaric acidemia type 2 is a very rare disorder. Its precise incidence is unknown. It has been reported in several different ethnic groups.[citation needed]

Treatment

It is important for patients with MADD to strictly avoid fasting to prevent hypoglycemia and crises of metabolic acidosis;[3][4] for this reason, infants and small children should eat frequent meals.[4] Patients with MADD can experience life-threatening metabolic crises precipitated by common childhood illnesses or other stresses on the body,[4] so avoidance of such stresses is critical.[3] Patients may be advised to follow a diet low in fat and protein and high in carbohydrates, particularly in severe cases.[3][4] Depending on the subtype, riboflavin[4] (100-400 mg/day),[3] coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10),[3] L-carnitine,[4] or glycine[4] supplements may be used to help restore energy production. Some small, uncontrolled studies[5][6][7] have reported that racemic salts of beta-hydroxybutyrate were helpful in patients with moderately severe disease; further research is needed.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Glutaric acidemia type II". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ↑ "Glutaric acidemia type II | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 "Multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency". Orphanet. INSERM and the European Commission. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "Glutaric acidemia type II". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ Gautschi M, Weisstanner C, Slotboom J, Nava E, Zürcher T, Nuoffer JM (January 2015). "Highly efficient ketone body treatment in multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency-related leukodystrophy". Pediatr Res. 77 (1): 91–8. doi:10.1038/pr.2014.154. PMID 25289702.

- ↑ Van Rijt WJ, Heiner-Fokkema MR, du Marchie Sarvaas GJ, Waterham HR, Blokpoel RG, van Spronsen FJ, Derks TG (October 2014). "Favorable outcome after physiologic dose of sodium-D,L-3-hydroxybutyrate in severe MADD". Pediatrics. 134 (4): e1224-8. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-4254. PMID 25246622. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ Van Hove JL, Grünewald S, Jaeken J, Demaerel P, Declercq PE, Bourdoux P, Niezen-Koning K, Deanfeld JE, Leonard JV (26 April 2003). "D,L-3-hydroxybutyrate treatment of multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MADD)". The Lancet. 361 (9367): 1433–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13105-4. PMID 12727399.

This article incorporates public domain text from The U.S. National Library of Medicine Archived 2019-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Classification |

|---|