Dysplastic nevus

| Dysplastic nevus | |

|---|---|

| |

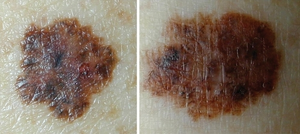

| Dysplastic nevus (left) and melanoma (right) | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

A dysplastic nevus or atypical mole is a nevus (mole) whose appearance is different from that of common moles.[1] It generally occurs in children and young adults, typically on the chest and scalp.[2] The nevus may be a flat spot or a small bump, with irregular border and distribution of color.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Dysplastic nevi often grow to larger than ordinary moles and may have irregular and indistinct borders. Their color may not be uniform and may range from light pink to very dark brown. They usually begin flat, but parts may be raised above the skin surface. See ABCDE and "ugly duckling" characteristics below.

Dysplastic nevi can be found anywhere, but are most common on the trunk in men, and on the calves in women.

There is some controversy in the dermatology community as to whether or not the "dysplastic"/"atypical" nevus exists. Some have argued that the terms "dysplastic" and "atypical" only refer to diagnostic uncertainty, as opposed to biologic uncertainty, and that the lesion is either a nevus or melanoma from the very beginning, as opposed to some kind of "premalignant stage"; it is only the clinician who is unsure. Some have also argued that even if such nevi do exist, studies have shown that clinicians are unable to reliably identify them anyway, meaning there is no point to even using the concept.[3][4][5][medical citation needed]

Cancer risk

As seen in Caucasian individuals in the United States, those with dysplastic nevi have a lifetime risk of developing melanoma of greater than 10%, compared to less than 1% for those without any dysplastic nevus.[6]

Precaution for individuals with dysplastic nevi

Although there are limited data to support its efficacy, skin self-examination is frequently recommended for preventing melanoma (by identifying atypical moles that can be removed) or for early detection of existing tumors. Examination by a dermatologist has been shown to be beneficial for early melanoma detection. Some dermatologists recommend that an individual with either histologic diagnosis of dysplastic nevus, or clinically apparent atypical moles should be examined by an experienced dermatologist with dermatoscopy once a year (or more frequently).

The abbreviation ABCDE has been useful for helping health care providers and laypersons remember the key characteristics of a melanoma (see "ABCDE" mnemonic below). Changes (in shape, size, color, itching or bleeding) should be brought to the attention of a dermatologist .[7]

A popular method for remembering the signs and symptoms of melanoma is the mnemonic "ABCDE":[8]

- Asymmetrical skin lesion.

- Border of the lesion is irregular.

- Color: melanomas usually have multiple colors.

- Diameter: moles greater than 6 mm are more likely to be melanomas than smaller moles.

- Evolution: The evolution (i.e. change) of a mole or lesion may be a hint that the lesion is becoming malignant.

The E is sometimes omitted, as in the ABCD guideline. A weakness in this system is the D. Many melanomas present themselves as lesions smaller than 6 mm in diameter. An astute physician will examine all abnormal moles, including ones less than 6 mm in diameter. Unfortunately for the average person, many seborrheic keratoses, some lentigo senilis, and even warts may have ABCD characteristics, and cannot be distinguished from a melanoma without a trained eye or dermatoscopy.

A recent and novel method of melanoma detection is the "Ugly Duckling Sign".[9][10] It is simple, easy to teach, and highly effective in detecting melanoma. Simply, correlation of common characteristics of a person's skin lesion is made. Lesions that greatly deviate from the common characteristics are labeled as an "Ugly Duckling", and a dermatologist exam is required. The "Little Red Riding Hood" sign[10] suggests that individuals with fair skin and light-colored hair might prove more challenging. These fair-skinned individuals often have lightly pigmented or amelanotic melanomas which will not present with easy to observe color changes and variation in colors. The borders of these amelanotic melanomas are often indistinct, making visual identification without a dermatoscope (dermatoscopy) very difficult. A dermatoscope must be used to detect "ugly ducklings" among those with light skin or blonde/red hair.

People with a personal or family history of skin cancer or of dysplastic nevus syndrome (multiple atypical moles) should see a dermatologist at least once a year to be sure they are not developing melanoma.

Biopsy

When an atypical mole has been identified, a skin biopsy takes place in order to best diagnose it. Local anesthetic is used to numb the area, then the mole is biopsied. The biopsy material is then sent to a laboratory to be evaluated by a pathologist. A skin biopsy can be a punch, shave, or complete excision. The complete excision is the preferred method, but a punch biopsy can suffice if the patient has cosmetic concerns (i.e. the patient does not want a scar) and the lesion is small. A scoop or deep shave biopsy is often advocated but should be avoided due to risk of a recurrent nevus, which can complicate future diagnosis of a melanoma, and the possibility that resulting scar tissue can obscure tumor depth if a melanoma is found to be present and re-excised.

Most dermatologists and dermatopathologists use a system devised by the NIH for classifying melanocytic lesions. In this classification, a nevus can be defined as benign, having atypia, or being a melanoma. A benign nevus is read as (or understood as) having no cytologic or architectural atypia. An atypical mole is read as having architectural atypia and having (mild, moderate, or severe) cytologic (melanocytic) atypia.[11] Usually, cytologic atypia is of more important clinical concern than architectural atypia. Usually, moderate to severe cytologic atypia will require further excision to make sure that the surgical margin is completely clear of the lesion.[citation needed]

The most important aspect of the biopsy report is that the pathologist indicates if the margin is clear (negative or free of melanocytic nevus), or if further tissue (a second surgery) is required. If this is not mentioned, usually a dermatologist or clinician will require further surgery if moderate to severe cytologic atypia is present – and if residual nevus is present at the surgical margin.

Dysplastic nevus syndrome

"Dysplastic nevus syndrome" refers to individuals who have high numbers of benign moles and also have dysplastic nevi. A small percent of these individuals are members of melanoma kindreds.[12] Inherited dysplastic nevus syndrome is an autosomal dominant hereditary condition. Dysplastic nevi are more likely to undergo malignant transformation when they occur among members of melanoma families. At least one study indicates a cumulative lifetime risk of nearly 100% in individuals who have dysplastic nevi and are members of melanoma kindreds.[citation needed] Roughly 70% of melanomas arise "de novo" on clear skin growth, whereas the rest arise within atypical moles.[13] Those with dysplastic nevi have an elevated risk of melanoma.[14][15] Such persons need to be checked regularly for any changes in their moles and to note any new ones. In 40-50% of cases, the disorder has been linked with germline mutations in the CDKN2A gene, which codes for p16 (a regulator of cell division).

Terminology

In 1992, the NIH recommended that the term "dysplastic nevus" be avoided in favor of the term "atypical mole".[16] An atypical mole may also be referred to as an atypical melanocytic nevus,[17] atypical nevus, B-K mole, Clark's nevus, dysplastic melanocytic nevus, or nevus with architectural disorder.[18]

Additional images

-

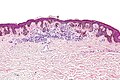

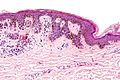

Low magnification

-

Intermediate magnification

-

Very high magnification

-

Micrograph of a dysplastic nevus showing the characteristic rete ridge bridging, shouldering, and lamellar fibrosis. H&E stain.

See also

References

- ↑ DE, Elder; D, Massi; RA, Scolyer; R, Willemze (2018). "2. Melanocytic tumours: dysplastic naevus". WHO Classification of Skin Tumours. Vol. 11 (4th ed.). Lyon (France): World Health Organization. pp. 82–86. ISBN 978-92-832-2440-2. Archived from the original on 2022-07-11. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "32. Lentigines, nevi and melanomas". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 548. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ↑ "Harald Kittler - Il mito della "displasia". Parte 1/3". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2019-12-16. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ↑ "Harald Kittler - Il mito della "displasia". Parte 2/3". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2020-01-03. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ↑ "Harald Kittler - Il mito della "displasia". Parte 3/3". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2019-12-16. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ↑ Dana Baigrie; Laura S. Tanner (2022). Dysplastic Nevi. StatPearls, at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 2022-05-16. Retrieved 2022-02-27. Last updated: January 20, 2019

- ↑ Friedman, R; Rigel, D; Kopf, A (1985). "Early detection of malignant melanoma: The role of physician examination and self-examination of the skin". CA Cancer J Clin. 35 (3): 130–51. doi:10.3322/canjclin.35.3.130. PMID 3921200.

- ↑ "Melanoma". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ↑ Scope, Alon. "The "Ugly Duckling" Sign: An Early Melanoma Recognition Tool For Clinicians and the Public". skincancer.org. Archived from the original on 2019-07-20. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Mascaro, JM Jr; Mascaro, JM (1998). "The dermatologist's position concerning nevi: A vision ranging from 'the ugly duckling' to 'little red riding hood'". Arch Dermatol. 134 (11): 1484–5. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.11.1484. PMID 9828892.

- ↑ Googe, Paul B. (31 March 1995). "Dysplastic nevi" (PDF). DermPath Update. KDL Pathology. 1 (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ↑ "dysplastic nevus syndrome" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Pampena R, Kyrgidis A, Lallas A, Moscarella E, Argenziano G, Longo C (2017). "A meta-analysis of nevus-associated melanoma: Prevalence and practical implications". J Am Acad Dermatol. 77 (5): 938–945.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.149. PMID 28864306. S2CID 11991994.

- ↑ Pope, DJ; Sorahan, T; Marsden, JR; Ball, PM; et al. (Sep 1992). "Benign pigmented nevi in children Prevalence and associated factors: the West Midlands, United Kingdom Mole Study". Arch. Dermatol. 128 (9): 1201–6. doi:10.1001/archderm.128.9.1201. PMID 1519934.

- ↑ Goldgar, DE; Cannon-Albright, LA; Meyer, LJ; Piepkorn, MW; et al. (Dec 1991). "Inheritance of nevus number and size in melanoma and dysplastic nevus syndrome kindreds". J Natl Cancer Inst. 83 (23): 1726–33. doi:10.1093/jnci/83.23.1726. PMID 1770551.

- ↑ "NIH Consensus conference. Diagnosis and treatment of early melanoma". JAMA. 268 (10): 1314–9. Sep 1992. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03490100112037. PMID 1507379.

- ↑ "dysplastic nevus" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 1732. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Pages with script errors

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2017

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2011

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2014

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Melanocytic nevi and neoplasms