Blunt trauma

| Blunt trauma | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Blunt injury, non-penetrating trauma, blunt force trauma | |

| |

| A woman with a black eye | |

| Symptoms | Bruising, occasionally complicated as hypoxia, ventilation-perfusion mismatch, hypovolemia, reduced cardiac output |

Blunt trauma is physical trauma or impactful force to a body part, often occurring with road traffic collisions, direct blows, assaults, injuries during sports, and particularly in the elderly who fall.[1][2] It is contrasted with penetrating trauma which occurs when an object pierces the skin and enters a tissue of the body, creating an open wound and bruise.[3]

Blunt trauma can result in contusions, abrasions, lacerations, internal hemorrhages, and bone fractures.[1]

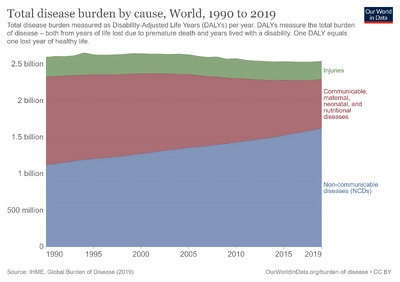

Worldwide, a significant cause of disability and death in people under the age of 35 years is trauma, of which most are due to blunt trauma.[1]

Classification

Blunt abdominal trauma

Blunt abdominal trauma (BAT) represents 75% of all blunt trauma and is the most common example of this injury.[4] 75% of BAT occur in motor vehicle accidents,[5] in which rapid deceleration may propel the driver into the steering wheel, dashboard, or seatbelt,[6] causing contusions in less serious cases, or rupture of internal organs from briefly increased intraluminal pressure in the more serious, depending on the force applied. Initially, there may be few indications that serious internal abdominal injury has occurred, making assessment more challenging and requiring a high degree of clinical suspicion.[7]

There are two basic physical mechanisms at play with the potential of injury to intra-abdominal organs: compression and deceleration.[8] The former occurs from a direct blow, such as a punch, or compression against a non-yielding object such as a seat belt or steering column. This force may deform a hollow organ, increasing its intraluminal or internal pressure and possibly lead to rupture.

Deceleration, on the other hand, causes stretching and shearing at the points where mobile contents in the abdomen, like bowel, are anchored. This can cause tearing of the mesentery of the bowel and injury to the blood vessels that travel within the mesentery. Classic examples of these mechanisms are a liver tear along the ligamentum teres and injuries to the renal arteries.

When blunt abdominal trauma is complicated by 'internal injury,' the liver and spleen (see blunt splenic trauma) are most frequently involved, followed by the small intestine.[9]

In rare cases, this injury has been attributed to medical techniques such as the Heimlich maneuver,[10] attempts at CPR and manual thrusts to clear an airway. Although these are rare examples, it has been suggested that they are caused by applying excessive pressure when performing these life-saving techniques. Finally, the occurrence of splenic rupture with mild blunt abdominal trauma in those recovering from infectious mononucleosis or ‘mono’ is well reported.[11]

Blunt abdominal trauma in sports

The supervised environment in which most sports injuries occur allows for mild deviations from the traditional trauma treatment algorithms, such as ATLS, due to the greater precision in identifying the mechanism of injury. The priority in assessing blunt trauma in sports injuries is separating contusions and musculo-tendinous injuries from injuries to solid organs and the gut and recognizing potential for developing blood loss, and reacting accordingly. Blunt injuries to the kidney from helmets, shoulder pads, and knees are described in American football,[12] association football, martial arts, and all-terrain vehicle accidents.

Blunt thoracic trauma

The term blunt thoracic trauma, or, more informally, blunt chest injury, encompasses a variety of injuries to the chest. Broadly, this also includes damage caused by direct blunt force (such as a fist or a bat in an assault), acceleration or deceleration (such as that from a rear-end automotive accident), shear force (a combination of acceleration and deceleration), compression (such as a heavy object falling on a person), and blasts (such as an explosion of some sort). Common signs and symptoms include something as simple as bruising, but occasionally as complicated as hypoxia, ventilation-perfusion mismatch, hypovolemia, and reduced cardiac output due to the way the thoracic organs may have been affected. Blunt thoracic trauma is not always visible from the outside and such internal injuries may not show signs or symptoms at the time the trauma initially occurs or even until hours after. A high degree of clinical suspicion may sometimes be required to identify such injuries, a CT scan may prove useful in such instances. Those experiencing more obvious complications from a blunt chest injury will likely undergo a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) which can reliably detect a significant amount of blood around the heart or in the lung by using a special machine that visualizes sound waves sent through the body. Only 10-15% of thoracic traumas require surgery, but they can have serious impacts on the heart, lungs, and great vessels.[13]

The most immediate life-threatening injuries that may occur include tension pneumothorax, open pneumothorax, hemothorax, flail chest, cardiac tamponade, and airway obstruction/rupture.[13]

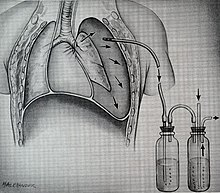

The injuries may necessitate a procedure, with the most common being the insertion of an intercostal drain, more commonly referred to as a chest tube. This tube is typically placed because it helps restore a certain balance in pressures (usually due to misplaced air or surrounding blood) that are impeding the lungs ability to inflate and thus exchange vital gases that allow the body to function.[14] A less common procedure that may be employed is a pericardiocentesis which by removing blood surrounding the heart, permits the heart to regain some ability to appropriately pump blood.[15][16] In certain dire circumstances an emergent thoracotomy may be employed.[17]

Blunt cranial trauma

The primary clinical concern with blunt trauma to the head is damage to the brain, although other structures, including the skull, face, orbits, and neck are also at risk.[9] Following assessment of the patient's airway, circulation, and breathing, a cervical collar may be placed if there is suspicion of trauma to the neck. Evaluation of blunt trauma to the head continues with the secondary survey for evidence of cranial trauma, including bruises, contusions, lacerations, and abrasions. In addition to noting external injury, a comprehensive neurologic exam is typically performed to assess for damage to the brain. Depending on the mechanism of injury and examination, a CT scan of the skull and brain may be ordered. This is typically done to assess for blood within the skull, or fracture of the skull bones.[18]

Traumatic brain injury

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality and is most commonly caused by falls, motor vehicle accidents, sports- and work-related injuries, and assaults. It is the most common cause of death in patients under the age of 25. TBI is graded from mild to severe, with greater severity correlating with increased morbidity and mortality.[18][19]

Most patients with more severe traumatic brain injury have of a combination of intracranial injuries, which can include diffuse axonal injury, cerebral contusions, and intracranial bleeding, including subarachnoid hemorrhage, subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, and intraparenchymal hemorrhage.[9][18] The recovery of brain function following a traumatic accident is highly variable and depends upon the specific intracranial injuries that occur, however there is significant correlation between the severity of the initial insult as well as the level of neurologic function during the initial assessment and the level of lasting neurologic deficits.[18] Initial treatment may be targeted at reducing the intracranial pressure if there is concern for swelling or bleeding within this skull, which may require surgery such as a hemicraniectomy, in which part of the skull is removed.[9][18]

Blunt trauma to extremities

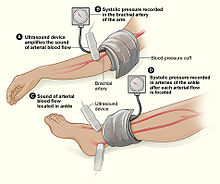

Injury to extremities (like arms, legs, hands, feet) is extremely common.[20] Falls are the most common etiology, making up as much as 30% of upper and 60% of lower extremity injuries. The most common mechanism for solely upper extremity injuries is machine operation or tool use. Work related accidents and vehicle crashes are also common causes.[21] The injured extremity is examined for four major functional components which include soft tissues, nerves, vessels, and bones.[22] Vessels are examined for expanding hematoma, bruit, distal pulse exam, and signs/symptoms of ischemia, essentially asking, “Does blood seem to be getting through the injured area in a way that enough is getting to the parts past the injury?”[23] When it is not obvious that the answer is “yes”, an injured extremity index or ankle-brachial index may be used to help guide whether further evaluation with computed tomography arteriography. This uses a special scanner and a substance that makes it easier to examine the vessels in finer detail than what the human hand can feel or the human eye can see.[24] Soft tissue damage can lead to rhabdomyolysis (a rapid breakdown of injured muscle that can overwhelm the kidneys) or may potentially develop compartment syndrome (when pressure builds up in muscle compartments damages the nerves and vessels in the same compartment).[25][26] Bones are evaluated with plain film x-ray or computed tomography if deformity (misshapen), bruising, or joint laxity (looser or more flexible than usual) are observed. Neurologic evaluation involves testing of the major nerve functions of the axillary, radial, and median nerves in the upper extremity as well as the femoral, sciatic, deep peroneal, and tibial nerves in the lower extremity. Surgical treatment may be necessary depending on the extent of injury and involved structures, but many are managed nonoperatively.[27]

Blunt pelvic trauma

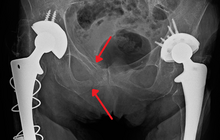

The most common causes of blunt pelvic trauma are motor vehicle accidents and multiple-story falls, and thus pelvic injuries are commonly associated with additional traumatic injuries in other locations.[28] In the pelvis specifically, the structures at risk include the pelvic bones, the proximal femur, major blood vessels such as the iliac arteries, the urinary tract, reproductive organs, and the rectum.[29][28]

One of the primary concerns is the risk of pelvic fracture, which itself is associated with a myriad of complications including bleeding, damage to the urethra and bladder, and nerve damage.[30] If pelvic trauma is suspected, emergency medical services personnel may place a pelvic binder on patients to stabilize the patient's pelvis and prevent further damage to these structures while patients are transported to a hospital. During the evaluation of trauma patients in an emergency department, the stability of the pelvis is typically assessed by the healthcare provider to determine whether fracture may have occurred. Providers may then decide to order imaging such as an X-ray or CT scan to detect fractures; however, if there is concern for life-threatening bleeding, patients should receive an X-ray of the pelvis.[31] Following initial treatment of the patient, fractures may need to be treated surgically if significant, while some minor fractures may heal without requiring surgery.[28]

A life-threatening concern is hemorrhage, which may result from damage to the aorta, iliac arteries or veins in the pelvis. The majority of bleeding due to pelvic trauma is due to injury to the veins.[30] Fluid (often blood) may be detected in the pelvis via ultrasound during the FAST scan that is often performed following traumatic accidents. Should a patient appear hemodynamically unstable in the absence of obvious blood on the FAST scan, there may be concern for bleeding into the retroperitoneal space, known as retroperitoneal hematoma. Stopping the bleeding may require endovascular intervention or surgery, depending on the location and severity.[29]

Diagnosis

In most settings, the initial evaluation and stabilization of traumatic injury follows the same general principles of identifying and treating immediately life-threatening injuries. In the US, the American College of Surgeons publishes the Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines, which provide a step-by-step approach to the initial assessment, stabilization, diagnostic reasoning, and treatment of traumatic injuries that codifies this general principle.[9] The assessment typically begins by ensuring that the subject's airway is open and competent, that breathing is unlabored, and that circulation—i.e. pulses that can be felt—is present. This is sometimes described as the "A, B, C's"—Airway, Breathing, and Circulation—and is the first step in any resuscitation or triage. Then, the history of the accident or injury is amplified with any medical, dietary (timing of last oral intake) and past history, from whatever sources such as family, friends, previous treating physicians that might be available. This method is sometimes given the mnemonic "SAMPLE". The amount of time spent on diagnosis should be minimized and expedited by a combination of clinical assessment and appropriate use of technology,[32] such as diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL), or bedside ultrasound examination (FAST)[33] before proceeding to laparotomy if required. If time and the patient's stability permits, CT examination may be carried out if available.[34] Its advantages include superior definition of the injury, leading to grading of the injury and sometimes the confidence to avoid or postpone surgery. Its disadvantages include the time taken to acquire images, although this gets shorter with each generation of scanners, and the removal of the patient from the immediate view of the emergency or surgical staff. Many providers use the aid of an algorithm such as the ATLS guidelines to determine which images to obtain following the initial assessment. These algorithms take into account the mechanism of injury, physical examination, and patient's vital signs to determine whether patients should have imaging or proceed directly to surgery.[9]

Recently, criteria have been defined that might allow patients with blunt abdominal trauma to be discharged safely without further evaluation. The characteristics of such patients include:

- absence of intoxication

- no evidence of lowered blood pressure or raised pulse rate

- no abdominal pain or tenderness

- no blood in the urine.

To be considered low risk, patients would need to meet all low-risk criteria.[35]

Treatment

When blunt trauma is significant enough to require evaluation by a healthcare provider, treatment is typically aimed at treating life-threatening injuries, which requires ensuring the patient is able to breathe and preventing ongoing blood loss. If there is evidence that the patient has lost blood, one or more intravenous lines may be placed and crystalloid solutions and/or blood will be administered at rates sufficient to maintain the circulation.[9] Some patients may require a surgical operation called an exploratory laparotomy to repair internal injuries.[9]

Epidemiology

Worldwide, a significant cause of disability and death in people under the age of 35 year is trauma, of which most are due to blunt trauma.[1]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Simon, Leslie V.; Lopez, Richard A.; King, Kevin C. (2020). "Blunt Force Trauma". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ↑ Cimino-Fiallos, Nicole (28 May 2020). "Hard Hits: Blunt Force Trauma". login.medscape.com. Medscape. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ↑ Shkrum, Michael J.; Ramsay, David A. "8. Blunt trauma: with reference to planes, trains and automobiles". Forensic Pathology of Trauma. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 406. ISBN 978-1-58829-458-6. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- ↑ Isenhour JL, Marx J (August 2007). "Advances in abdominal trauma". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 25 (3): 713–33, ix. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2007.06.002. PMID 17826214.

- ↑ "Assessment of abdominal trauma - Differential diagnosis of symptoms | BMJ Best Practice". bestpractice.bmj.com. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ↑ Bansal V, Conroy C, Tominaga GT, Coimbra R (December 2009). "The utility of seat belt signs to predict intra-abdominal injury following motor vehicle crashes". Traffic Injury Prevention. 10 (6): 567–72. doi:10.1080/15389580903191450. PMID 19916127.

- ↑ Fitzgerald JE, Larvin M (2009). "Chapter 15: Management of Abdominal Trauma". In Baker Q, Aldoori M (eds.). Clinical Surgery: A Practical Guide. CRC Press. pp. 192–204. ISBN 978-1-4441-0962-7.

- ↑ Mukhopadhyay M (October 2009). "Intestinal Injury from Blunt Abdominal Trauma: A Study of 47 Cases". Oman Med J. 24 (4): 256–259. doi:10.5001/omj.2009.52. PMC 3243872. PMID 22216378.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Advanced Trauma Life Support Student Course Manual (PDF) (9th ed.). American College of Surgeons. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ↑ Mack L, Forbes TL, Harris KA (January 2002). "Acute aortic thrombosis following incorrect application of the Heimlich maneuver". Ann Vasc Surg. 16 (1): 130–3. doi:10.1007/s10016-001-0147-z. PMID 11904818.

- ↑ O'Connor TE, Skinner LJ, Kiely P, Fenton JE (August 2011). "Return to contact sports following infectious mononucleosis: the role of serial ultrasonography". Ear Nose Throat J. 90 (8): E21–4. PMID 21853428.

- ↑ Brophy RH, Gamradt SC, Barnes RP, Powell JW, DelPizzo JJ, Rodeo SA, Warren RF (January 2008). "Kidney injuries in professional American football: implications for management of an athlete with 1 functioning kidney". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 36 (1): 85–90. doi:10.1177/0363546507308940. PMID 17986635.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Blyth A (March 2014). "Thoracic trauma". BMJ. 348: g1137. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1137. PMID 24609501.

- ↑ Falter F, Nair S (2012). Intercostal Chest Drain Insertion. Bedside Procedures in the ICU. Springer, London. pp. 105–111. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-2259-3_10. ISBN 9781447122586.

- ↑ Maisch B, Ristić AD, Seferović PM, Tsang TS (2011). Interventional Pericardiology. Berlin: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11335-2. ISBN 978-3-642-11334-5. OCLC 1036224056.

- ↑ Bhargava M, Wazni OM, Saliba WI (March 2016). "Interventional Pericardiology". Current Cardiology Reports. 18 (3): 31. doi:10.1007/s11886-016-0698-9. PMID 26908116.

- ↑ Platz JJ, Fabricant L, Norotsky M (August 2017). "Thoracic Trauma: Injuries, Evaluation, and Treatment". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 97 (4): 783–799. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2017.03.004. PMID 28728716.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Haydel, Micelle; Scott, Dulebohn. "Blunt Head Trauma". StatPearls. PubMed. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ↑ Nickson, Chris. "Traumatic Brain Injury". Life in the Fast Lane. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ↑ de Mestral C, Sharma S, Haas B, Gomez D, Nathens AB (February 2013). "A contemporary analysis of the management of the mangled lower extremity". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 74 (2): 597–603. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31827a05e3. PMID 23354257.

- ↑ Søreide K (July 2009). "Epidemiology of major trauma". The British Journal of Surgery. 96 (7): 697–8. doi:10.1002/bjs.6643. PMID 19526611.

- ↑ Johansen K, Daines M, Howey T, Helfet D, Hansen ST (May 1990). "Objective criteria accurately predict amputation following lower extremity trauma". The Journal of Trauma. 30 (5): 568–72, discussion 572–3. doi:10.1097/00005373-199005000-00007. PMID 2342140.

- ↑ "Annual Report of the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB)". www.facs.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-23. Retrieved 2018-12-16.

- ↑ Lynch K, Johansen K (December 1991). "Can Doppler pressure measurement replace "exclusion" arteriography in the diagnosis of occult extremity arterial trauma?". Annals of Surgery. 214 (6): 737–41. doi:10.1097/00000658-199112000-00016. PMC 1358501. PMID 1741655.

- ↑ Egan AF, Cahill KC (November 2017). "Compartment Syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (19): 1877. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1701729. PMID 29117495.

- ↑ Bosch X, Poch E, Grau JM (July 2009). "Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (1): 62–72. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0801327. PMID 19571284.

- ↑ Kennedy RH (September 1932). "Emergency Treatment of Extremity Fractures". New England Journal of Medicine. 207 (9): 393–395. doi:10.1056/NEJM193209012070903.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 2013-04-26. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Geeraerts, Thomas; Chhor, Vibol; Cheisson, Gaëlle; Martin, Laurent; Bessoud, Bertrand; Ozanne, Augustin; Duranteau, Jacques (2007). "Clinical review: Initial management of blunt pelvic trauma patients with haemodynamic instability". Critical Care. 11 (1): 204. doi:10.1186/cc5157. ISSN 1364-8535. PMC 2151899. PMID 17300738.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Nickson, Chris. "Pelvic Trauma". Life in the Fast Lane. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ↑ Croce, Martin. "Initial Management of Pelvic Fractures". FACS. American College of Surgeons. Archived from the original on 2015-04-21. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- ↑ Woods SD (February 1995). "Assessment of blunt abdominal trauma". Aust N Z J Surg. 65 (2): 75–6. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.1995.tb07263.x. PMID 7857232.

- ↑ Marco GG, Diego S, Giulio A, Luca S (October 2005). "Screening US and CT for blunt abdominal trauma: a retrospective study". Eur J Radiol. 56 (1): 97–101. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2005.02.001. PMID 16168270.

- ↑ Jansen JO, Yule SR, Loudon MA (April 2008). "Investigation of blunt abdominal trauma". BMJ. 336 (7650): 938–42. doi:10.1136/bmj.39534.686192.80. PMC 2335258. PMID 18436949.

- ↑ Kendall JL, Kestler AM, Whitaker KT, Adkisson MM, Haukoos JS (November 2011). "Blunt abdominal trauma patients are at very low risk for intra-abdominal injury after emergency department observation". West J Emerg Med. 12 (4): 496–504. doi:10.5811/westjem.2010.11.2016. PMC 3236146. PMID 22224146.