Rivastigmine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Exelon, Prometax, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Cholinesterase inhibitor[1] |

| Main uses | Dementia[1] |

| Side effects | Nausea, confusion, hallucinations, problems sleeping[2][3] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, transdermal patch |

| Typical dose | By mouth: 3 to 6 mg BID[3] Patch: 4.6 to 13.3 mg/24 hr[3] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a602009 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 60 to 72% |

| Protein binding | 40% |

| Metabolism | Liver, via pseudocholinesterase |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5 hours |

| Excretion | 97% in urine |

| Chemical and physical data | |

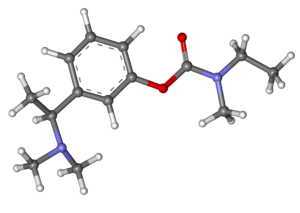

| Formula | C14H22N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 250.342 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Rivastigmine, sold under the brand name Exelon among others, is a medication used to treat dementia in Alzheimer's or Parkinson's.[1] Benefits are modest and use does not affect the underlying disease.[1] It is taken by mouth or via a skin patch.[1]

Common side effects include nausea, confusion, hallucinations, and problems sleeping.[2][3] Other side effects may include slow heart rate, urinary obstruction, seizures, and allergic dermatitis.[1] It is a cholinesterase inhibitor which increases acetylcholine in the brain.[1]

Rivastigmine was patented in 1985 and came into medical use in 1997.[4] It was approved for medical use in Europe in 1998 and the United States in 2000.[3][1] It is available as a generic medication.[2] In the United Kingdom it costs about £5 per month for the pills as of 2021.[2] In the United States this amount costs about 27 USD.[5]

Medical uses

Rivastigmine capsules, liquid solution and patches are used for the treatment of mild to moderate dementia of the Alzheimer's type and for mild to moderate dementia related to Parkinson's disease.

Rivastigmine has demonstrated treatment effects on the cognitive (thinking and memory), functional (activities of daily living) and behavioural problems commonly associated with Alzheimer's[6][7][8][9] and Parkinson's disease dementias.[10]

Efficacy

In people with either type of dementia, rivastigmine has been shown to provide meaningful symptomatic effects that may allow patients to remain independent and ‘be themselves’ for longer. In particular, it appears to show marked treatment effects in patients showing a more aggressive course of disease, such as those with younger onset ages, poor nutritional status, or those experiencing symptoms such as delusions or hallucinations.[11] For example, the presence of hallucinations appears to be a predictor of especially strong responses to rivastigmine, both in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's patients.[12][13] These effects might reflect the additional inhibition of butyrylcholinesterase, which is implicated in symptom progression and might provide added benefits over acetylcholinesterase-selective drugs in some patients.[11][12] Multiple-infarct dementia patients may show slight improvement in executive functions and behaviour. No firm evidence supports usage in schizophrenia patients.

Its efficacy is similar to donepezil and tacrine. Doses below 6 mg/d may be ineffective. The effects of this kind of drug in different kinds of dementia (including Alzheimer's dementia) are modest, and it is still unclear which AChE (BChE) esterase inhibitor is better in Parkinson's dementia, though rivastigmine is well-studied.

Administration

It comes in a variety of administrations including a capsule, solution and a transdermal patch. Like other cholinesterase inhibitors, it requires doses to be increased gradually over several weeks; this is usually referred to as the titration phase.[14]

By mouth it should be titrated with a 3 mg per day increment every 2 to 4 weeks. An initial dose of 1.5 mg twice daily is recommended followed by an increase by 1.5 mg/dose after four weeks. The dose should increase as long as side effects are tolerable. Patients should be reminded to take with food. For the transdermal patch, an initial dose of 4.6 mg per day increases to 9.5 mg per day after four weeks if the patient is not experiencing any intolerable side effects.[15] Patients or caregivers should be reminded to remove the old patch every day, rotate sites and place a new one. It is recommended that the patch be applied to the upper back or torso.[16]

Side effects

Side effects may include nausea and vomiting, decreased appetite and weight loss.[14]

The strong potency of rivastigmine, provided by its dual inhibitory mechanism, has been postulated to lead to more nausea and vomiting during the titration phase of oral rivastigmine treatment.[14] This enforces the importance of taking oral forms of these drugs with food as prescribed.[17] However, rates of nausea and vomiting are markedly reduced with the once-daily rivastigmine patch (which can be applied at any time of the day, with or without food). Patients and caregivers should be aware of warning signs of potential toxicities and know when to call their doctor. For the patch and oral formulations, skin rashes can occur at which time patients should contact their doctor immediately.[15] For the patch, patients and caregivers should monitor for any intense itching, redness, swelling or blistering at the patch location. If this occurs, remove the patch, rinse the area and call the doctor immediately.[16]

In a large clinical trial of the rivastigmine patch in 1,195 patients with Alzheimer's disease, the target dose of 9.5 mg/24-hour patch provided similar clinical effects (e.g. memory and thinking, activities of daily living, concentration) as the highest doses of rivastigmine capsules, but with one-third fewer reports of nausea and vomiting.[18]

Usage of rivastigmine was associated with a higher frequency of reports of death as an adverse event in the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System database compared to the other acetylcholinesterase inhibiting drugs donepezil and galantamine.[19]

Rivastigmine is classified as pregnancy category B, with insufficient data on risks associated with breastfeeding. In cases of overdose, atropine is used to reverse bradycardia. Dialysis is ineffective due to the drug's half-life.[citation needed]

Pharmacodynamics

Rivastigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, inhibits both butyrylcholinesterase and acetylcholinesterase (unlike donepezil, which selectively inhibits acetylcholinesterase). It is thought to work by inhibiting these cholinesterase enzymes, which would otherwise break down the brain neurotransmitter acetylcholine.[20]

Pharmacokinetics

When given by mouth, rivastigmine is well absorbed, with a bioavailability of about 40% in the 3-mg dose. Pharmacokinetics are linear up to 3 mg BID, but nonlinear at higher doses. Elimination is through the urine. Peak plasma concentrations are seen in about one hour, with peak cerebrospinal fluid concentrations at 1.4–3.8 hours. When given by once-daily transdermal patch, the pharmacokinetic profile of rivastigmine is much smoother, compared with capsules, with lower peak plasma concentrations and reduced fluctuations.[21] The 9.5 mg/24 h rivastigmine patch provides comparable exposure to 12 mg/day capsules (the highest recommended oral dose).[21]

The compound does cross the blood–brain barrier. Plasma protein binding is 40%.[22] The major route of metabolism is by its target enzymes via cholinesterase-mediated hydrolysis. Elimination bypasses the hepatic system, so hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes are not involved.[23] The low potential for drug-drug interactions (which could lead to adverse effects) has been suggested as due to this pathway compared to the many common drugs that use the cytochrome P450 metabolic pathway.[14]

The drug is eliminated through the urine, and appears to have relatively few drug-drug interactions.[14]

Chemistry

Rivastigmine tartrate is a white to off-white, fine crystalline powder that is both lipophilic (soluble in fats) and hydrophilic (soluble in water).

History

Rivastigmine was developed by Marta Weinstock-Rosin of the Department of Pharmacology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem[24] and sold to Novartis by Yissum for commercial development. It is a semi-synthetic derivative of physostigmine.[25] It has been available in capsule and liquid formulations since 1997.[17] In 2006, it became the first product approved globally for the treatment of mild to moderate dementia associated with Parkinson's disease;[26] and in 2007 the rivastigmine transdermal patch became the first patch treatment for dementia.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 "Rivastigmine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Prometax". Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 540. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ↑ "Rivastigmine Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ↑ Corey-Bloom, J.; Anand, R.; Veach, J. (1998). "A randomized trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of ENA 713 (rivastigmine tartrate), a new acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, in patients with mild to moderately severe Alzheimer's disease". International Journal of Geriatric Psychopharmacology. 1 (2): 55–65. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ↑ Rosler, M.; Anand, R.; Cicin-Sain, A.; Gauthier, S.; Agid, Y.; Dal-Bianco, P.; Stähelin, H. B.; Hartman, R.; Gharabawi, M.; Bayer, T. (1999). "Efficacy and safety of rivastigmine in patients with Alzheimer's disease: International randomised controlled trial Commentary: Another piece of the Alzheimer's jigsaw". BMJ. 318 (7184): 633–638. doi:10.1136/bmj.318.7184.633. PMC 27767. PMID 10066203.

- ↑ Finkel, S. I. (2004). "Effects of rivastigmine on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Alzheimer's disease". Clinical Therapeutics. 26 (7): 980–990. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(04)90172-5. PMID 15336465.

- ↑ Rösler, M.; Retz, W.; Retz-Junginger, P.; Dennler, H. J. (1998). "Effects of two-year treatment with the cholinesterase inhibitor rivastigmine on behavioural symptoms in Alzheimer's disease". Behavioural Neurology. 11 (4): 211–216. doi:10.1155/1999/168023. PMID 11568422.

- ↑ Emre, M.; Aarsland, D.; Albanese, A.; Byrne, E. J.; Deuschl, G. N.; De Deyn, P. P.; Durif, F.; Kulisevsky, J.; Van Laar, T.; Lees, A.; Poewe, W.; Robillard, A.; Rosa, M. M.; Wolters, E.; Quarg, P.; Tekin, S.; Lane, R. (2004). "Rivastigmine for Dementia Associated with Parkinson's Disease" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (24): 2509–2518. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041470. PMID 15590953. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Gauthier, S.; Vellas, B.; Farlow, M.; Burn, D. (2006). "Aggressive course of disease in dementia". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2 (3): 210–217. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2006.03.002. PMID 19595889. S2CID 30562189.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Touchon, J.; Bergman, H.; Bullock, R.; Rapatz, G. N.; Nagel, J.; Lane, R. (2006). "Response to rivastigmine or donepezil in Alzheimer's patients with symptoms suggestive of concomitant Lewy body pathology". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 22 (1): 49–59. doi:10.1185/030079906X80279. PMID 16393430. S2CID 29977831.

- ↑ Burn, D.; Emre, M.; McKeith, I.; De Deyn, P. P.; Aarsland, D.; Hsu, C.; Lane, R. (2006). "Effects of rivastigmine in patients with and without visual hallucinations in dementia associated with Parkinson's disease". Movement Disorders. 21 (11): 1899–1907. doi:10.1002/mds.21077. PMID 16960863. S2CID 24621350.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Inglis, F. (2002). "The tolerability and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of dementia". International Journal of Clinical Practice. Supplement (127): 45–63. PMID 12139367.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Archive copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)[full citation needed] - ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Treat Alzheimer's | Exelon® Patch (Rivastigmine transdermal system)". Archived from the original on 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation "Exelon Product Insert" June 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-29. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ↑ Winblad, B.; Grossberg, G.; Frölich, L.; Farlow, M.; Zechner, S.; Nagel, J.; Lane, R. (2007). "IDEAL: A 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the first skin patch for Alzheimer disease". Neurology. 69 (4 Suppl 1): S14–S22. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000281847.17519.e0. PMID 17646619. S2CID 38846813.

- ↑ Ali TB, Schleret TR, Reilly BM, Chen WY, Abagyan R (2015). "Adverse Effects of Cholinesterase Inhibitors in Dementia, According to the Pharmacovigilance Databases of the United-States and Canada". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0144337. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1044337A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144337. PMC 4671709. PMID 26642212.

- ↑ Camps, P. Munoz-Torrero D. (Feb 2002). "Cholinergic drugs in pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer's disease". Mini Rev Med Chem. 2 (1): 11–25. doi:10.2174/1389557023406638. PMID 12369954.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Cummings, J.; Lefevre, G.; Small, G.; Appel-Dingemanse, S. (2007). "Pharmacokinetic rationale for the rivastigmine patch". Neurology. 69 (4 Suppl 1): S10–13. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000281846.40390.50. PMID 17646618. S2CID 21290898.

- ↑ Jann, M. W.; Shirley, K. L.; Small, G. W. (2002). "Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Cholinesterase Inhibitors". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 41 (10): 719–739. doi:10.2165/00003088-200241100-00003. PMID 12162759. S2CID 22768375.

- ↑ Jann, M. W. (2000). "Rivastigmine, a New-Generation Cholinesterase Inhibitor for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease". Pharmacotherapy. 20 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1592/phco.20.1.1.34664. PMID 10641971. S2CID 25007829.

- ↑ "Exelon". Yissum Technology Transfer. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ↑ Kumar, V. (2006). "Potential medicinal plants for CNS disorders: An overview". Phytotherapy Research. 20 (12): 1023–1035. doi:10.1002/ptr.1970. PMID 16909441. S2CID 25213417.

- ↑ "Approves the First Treatment for Dementia of Parkinson's Disease U.S. FDA News Release". Archived from the original on 2020-04-24. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: date format

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- All articles with incomplete citations

- Articles with incomplete citations from January 2016

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drug has EMA link

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2018

- Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors

- Antidementia agents

- Novartis brands

- Aromatic carbamates

- Israeli inventions

- RTT