Anemia in pregnancy

| Anemia in pregnancy | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

| Symptoms | Tiredness, pale skin, palpitations, weakness[1] |

| Complications | Mother: Blood transfusions, post-partum depression, heart problems, risk of death[2][1] Baby: Premature birth, low birth weight[3] |

| Prevention | Eating a healthy diet, > 2 yrs between pregnancies, prenatal supplements[3][2] |

| Treatment | Iron supplements, blood transfussions[2] |

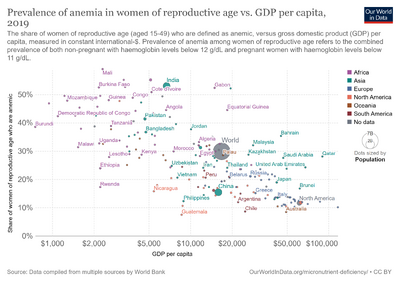

| Frequency | 5% (USA), > 80% (certain developing countries)[4] |

Anemia in pregnancy is a decrease in red blood cells (RBCs) or hemoglobin in the blood during pregnancy.[2] Symptoms in the mother are usually non-specific, but can include tiredness, pale skin, palpitations, shortness of breath, and weakness.[1][5] Complications in the mother may include a need for blood transfusions, post-partum depression, heart problems, and risk of death.[2][1] Complications for the child may include premature birth and low birth weight.[3]

It most commonly occurs due to iron deficiency and blood loss; though, other types do occur.[2] Routine testing is recommended.[2] Diagnosis is based on a first or third trimester hemoglobin of less than 110 g/L or hematocrit less than 33%; or second trimester hemoglobin of less than 105 g/L or hematocrit less than 32%.[2] Iron tests, such as serum ferritin, may rule out iron deficiency.[2] Types may be further classified based on the mean cell volume.[2]

Efforts to prevent anemia include eating a healthy diet, waiting at least two years between pregnancies, and prenatal supplements.[3][2] Treatment may include additional iron supplements.[2] In iron deficiency improvements should occur over a few weeks.[2] In folate deficiency folate supplements may be taken.[5] In severe anemia with hemoglobin levels less than 60 g/L, blood transfusions may be recommended.[2]

Anemia in pregnancy is common.[6] Rates vary from 5% in the United States to over 80% in certain developing countries.[4] It is even more common in teenage pregnancy.[2] The World Health Organization states that spending to treat anemia in women provides a twelve fold return on investment.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Common symptoms are headache, fatigue, lethargy, tachycardia, tachypnea, paresthesia, pallor, glossitis and cheilitis.[7][8] Severe symptoms include congestive heart failure, placenta previa, abruptio placenta, and operative delivery.[7][9]

Complications

Mother

Studies have suggested that severe maternal morbidity (SMM) is increased approximately twofold in antepartum maternal anemia. SMM is defined by maternal death, eclampsia, transfusion, hysterectomy, or intensive care unit admission at delivery. Additional complications may include postpartum haemorrhage, preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, and infections.[10]

Child

Iron deficiency during pregnancy is linked to a number of harmful effects on the fetus such as intrauterine growth restriction, death in utero, infection, preterm delivery and neurodevelopmental damage, which may be irreversible.[11][12][13]

Causes

In the simplest of terms, anemia results from impaired production of red blood cells, increased destruction of red blood cells or blood loss. Anemia can be congenital (i.e. conditions such as sickle cell anemia and thalassemia) or acquired (i.e., conditions such as iron-deficiency anemia or anemia as a result of an infection). The causes of anemia during pregnancy can be subdivided into two main categories; physiologic and non-physiologic causes.[citation needed]

Physiologic

Dilutional anemia: There is an increase in overall blood volume during pregnancy, and even though there is an increase in overall red blood cell mass, the increase in the other parts of the blood like plasma decrease the overall percentage of red blood cells in circulation.[14]

Non-physiologic

Iron deficiency anemia: this can occur from the increased production of red blood cells, which requires a lot of iron and also from inadequate intake of iron, which increase in pregnancy.[8]

Hemoglobinopathies: Thalassemia and sickle cell disease

Dietary deficiencies: Folate deficiency and vitamin B12 deficiency are common causes of anemia in pregnancy. Folate deficiency occurs due to diets low in lefty green vegetables, and animal sources of protein.[15] B12 deficiency tends to be more common in individuals with Crohn's disease or gastrectomies.[16]

Cell membrane disorders: Hereditary spherocytosis

Autoimmune causes: lead to the hemolysis of red blood cells (Ex: autoimmune hemolytic anemia).[17]

Hypothyroidism and chronic kidney disease[18][19]

Parasitic infestations: some examples are hookworm or Plasmodium species

Bacterial or viral infections

Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia in the pregnant woman. During pregnancy, the average total iron requirement is about 1200 mg per day for a 55 kg woman. This iron is used for the increase in red cell mass, placental needs and fetal growth. About 40% of women start their pregnancy with low to absent iron stores and up to 90% have iron stores insufficient to meet the increased iron requirements during pregnancy and the postpartum period.[citation needed]

The majority of women presenting with postpartum anemia have pre-delivery iron deficiency anemia or iron deficiency anemia combined with acute blood loss during delivery.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

The most useful test with which to render a diagnosis of anemia is a low RBC count, however hemoglobin and hematocrit values are most commonly used in making the initial diagnosis of anemia. Testing involved in diagnosing anemia in pregnant women must be tailored to each individual patient. Suggested tests include: hemoglobin and hematocrit (ratio of red blood cells to the total blood volume), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), erythrocyte count (number of red blood cells in the blood), red cell distribution width (RDW), reticulocyte count, and a peripheral smear to assess red blood cell morphology. If iron deficiency is suspected, additional tests such as: serum iron, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), transferrin saturation, and plasma or serum ferritin may be warranted. It is important to note that references ranges for these values are often not the same for pregnant women. Additionally, laboratory values for pregnancy often change throughout the duration of a woman's gestation. For example, the reference values for what level of hemoglobin is considered anemic varies in each trimester of pregnancy.[20][14]

- First trimester hemoglobin < 11 g/dL

- Second trimester hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL

- Third trimester hemoglobin < 11 g/dL

- Postpartum hemoglobin < 10 g/dL

Listed below are normal ranges for important lab values in the diagnosis of anemia. Keep in mind that these ranges might change based on each patient's stage in pregnancy:[8]

- Hemoglobin: Men (13.6-16.9), women (11.9-14.8)

- Hematocrit: Men (40-50%), women (35-43%)

- MCV: 82.5 - 98

- Reticulocyte count: Men (16-130X10^3/microL or X10^9), Women (16-98/microL or X10^9)

Based on MCV

MCV can be a great measure for differentiating between different forms of anemia. MCV measures the average size of your red blood cells. There are three cut off measurements for MCV. If the MCV is < 80fL it is considered microcytic. If the MCV is from 80 to 100 fL then it is considered a normocytic anemia. If the MCV is > 100 fL it is considered a macrocytic anemia. Some causes of anemia can be characterized by different ranges of MCV depending upon the severity disease. Here are common causes of anemia organized by MCV.[21]

MCV < 80 fL

- Anemia of chronic disease or anemia of inflammation

MCV 80 - 100 fL

- Iron deficiency

- Infection

- Liver disease or alcohol use

- Drug-induced

- Vitamin B12 or folate deficiency

MCV > 100 fL

- Vitamin B12 or folate deficiency

- Drug induced

- Liver disease or alcohol use

- Hypothyroidism

Pregnancy

Pregnant women need almost twice as much iron as women who are not pregnant. Not getting enough iron during pregnancy raises risk of premature birth or a low-birth-weight baby.[22] Hormonal changes in the pregnant woman result in an increase in circulating blood volume to 100 mL/kg with a total blood volume of approximately 6000–7000 mL. While red cell mass increases by 15–20% during pregnancy, plasma volume increases by 40%.[23] Hemoglobin levels less than 11 g/dL during the first trimester, less than 10.5 g/dL during the second and third trimesters and less than 10 mg/dL in the postpartum period are considered anemic.[24]

Prevention

Anemia is a very common complication of pregnancy. A mild form of anemia can be a result of dilution of blood. There is a relatively larger increase in blood plasma compared to total red cell mass in all pregnancies, which results in dilution of the blood and causes physiologic anemia . These changes take place to ensure adequate amount of blood is supplied to the fetus and prepares body for expected blood loss at the time of delivery.[25]

More severe forms of anemia can be a due to iron deficiency, vitamin deficiency, or other causes.[citation needed]

Iron deficiency

Iron deficiency is the most common cause of non-physiologic anemia. Iron deficiency anemia can be prevented with supplemental oral iron 27–30 mg daily.[26] This dose typically corresponds to the amount of iron found in iron-containing prenatal vitamins. Consult with your medical provider to determine whether additional supplements are needed. Complete routine labs during pregnancy for early detection of iron deficiency anemia.[26]

Iron deficiency anemia can also be prevented by eating iron-rich foods. This includes dark green leafy vegetables, eggs, meat, fish, dried beans, and fortified grains.[27]

Other causes

This may be only applicable to select individuals.

Vitamin B12: Women who consume strictly vegan diets are advised to take Vitamin B12 supplements; this helps prevent anemia due to low Vitamin B12 levels.[28]

Folic acid: Folic acid supplement recommended for women with history of documented folate deficiency. Folic acid supplementation also recommended for prevention of neural tube defects in the fetus.[28]

Treatment

For treatment of iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women, iron supplementation at doses higher than prenatal supplements is recommended. The standard doses of oral iron ranges from 40 mg to 200 mg elemental iron daily.[29] Consult with your medical provider to determine the exact dose needed for your condition, higher than needed doses of iron supplements may sometimes lead to more adverse effects.[20]

Iron supplements are easy to take, however adverse effects in some cases may include gastrointestinal side effects, nausea, diarrhea, and/or constipation. In cases when oral iron supplement is not tolerable, other options include longer intervals between each oral dose, liquid iron supplements, or intravenous iron.[20] Intravenous iron may also be used in cases of severe iron deficiency anemia during second and third trimesters of pregnancy.[30]

Anemias due to other deficiencies such as folic acid or vitamin B12 can also be treated with supplementation as well; dose may vary based on level of deficiency.[citation needed]

Other forms of anemias, such as inherited or acquired anemias prior to pregnancy, will require continuous management during pregnancy as well.[28]

Treatment should target the underlying disease or condition affecting the patient.

- The majority of obstetric anemia cases can be treated based on their etiology if diagnosed in time. Oral iron supplementation is the gold standard for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia and intravenous iron can be used when oral iron is not effective or tolerated from the second trimester of pregnancy onwards.[31]

- Treatment of postpartum hemorrhage is multifactorial and includes medical management, surgical management along with blood product support.[32][33]

Epidemiology

According to the WHO estimation, the global prevalence of anemia during pregnancy is over 40%, and the prevalence of anemia during pregnancy in North America is 6%.[34] Prevalence of anemia in pregnancy is higher in developing countries compared to developed countries. 56% of pregnant women from low and middle income countries were reported to have anemia.[35]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Breymann, Christian (October 2015). "Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnancy". Seminars in Hematology. 52 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.07.003. ISSN 1532-8686. PMID 26404445.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 "Anemia in Pregnancy: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 233". Obstetrics and gynecology. 138 (2): e55–e64. 1 August 2021. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004477. PMID 34293770.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Anaemia". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sun, D; McLeod, A; Gandhi, S; Malinowski, AK; Shehata, N (December 2017). "Anemia in Pregnancy: A Pragmatic Approach". Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 72 (12): 730–737. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000510. PMID 29280474.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Anemia During Pregnancy - Women's Health Issues". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ↑ "Anemia - Anemia in Pregnancy | NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. 24 March 2022. Archived from the original on 11 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Sifakis, S.; Pharmakides, G. (2000). "Anemia in Pregnancy". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 900 (1): 125–136. Bibcode:2000NYASA.900..125S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06223.x. ISSN 1749-6632. PMID 10818399. S2CID 6740558.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- ↑ Flessa, H. C. (December 1974). "Hemorrhagic disorders and pregnancy". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 17 (4): 236–249. doi:10.1097/00003081-197412000-00015. ISSN 0009-9201. PMID 4615860. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ↑ Harrison, Rachel K.; Lauhon, Samantha R.; Colvin, Zachary A.; McIntosh, Jennifer J. (September 2021). "Maternal anemia and severe maternal morbidity in a US cohort". American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM. 3 (5): 100395. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100395. PMC 8435012. PMID 33992832.

- ↑ Geng, Fengji; Mai, Xiaoqin; Zhan, Jianying; Xu, Lin; Zhao, Zhengyan; Georgieff, Michael; Shao, Jie; Lozoff, Betsy (December 2015). "Impact of Fetal-Neonatal Iron Deficiency on Recognition Memory at 2 Months of Age". The Journal of Pediatrics. 167 (6): 1226–1232. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.08.035. ISSN 1097-6833. PMC 4662910. PMID 26382625.

- ↑ Beard, John L. (December 2008). "Why iron deficiency is important in infant development". The Journal of Nutrition. 138 (12): 2534–2536. doi:10.1093/jn/138.12.2534. ISSN 1541-6100. PMC 3415871. PMID 19022985.

- ↑ Lozoff, Betsy; Beard, John; Connor, James; Barbara, Felt; Georgieff, Michael; Schallert, Timothy (May 2006). "Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy". Nutrition Reviews. 64 (5 Pt 2): S34–43, discussion S72–91. doi:10.1301/nr.2006.may.S34-S43. ISSN 0029-6643. PMC 1540447. PMID 16770951.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics (2021-08-01). "Anemia in Pregnancy: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 233". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 138 (2): e55–e64. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004477. ISSN 1873-233X. PMID 34293770. S2CID 236198933. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ↑ Campbell, B. A. (September 1995). "Megaloblastic anemia in pregnancy". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 38 (3): 455–462. doi:10.1097/00003081-199509000-00005. ISSN 0009-9201. PMID 8612357. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ↑ Parrott, Julie; Frank, Laura; Rabena, Rebecca; Craggs-Dino, Lillian; Isom, Kellene A.; Greiman, Laura (May 2017). "American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Integrated Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient 2016 Update: Micronutrients". Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 13 (5): 727–741. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.018. ISSN 1878-7533. PMID 28392254. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ↑ "Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-01-31. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ Green, S. T.; Ng, J. P. (1986). "Hypothyroidism and anaemia". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 40 (9): 326–331. ISSN 0753-3322. PMID 3828479. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ↑ "Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Pavord, Sue; Daru, Jan; Prasannan, Nita; Robinson, Susan; Stanworth, Simon; Girling, Joanna; BSH Committee (March 2020). "UK guidelines on the management of iron deficiency in pregnancy". British Journal of Haematology. 188 (6): 819–830. doi:10.1111/bjh.16221. ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 31578718. S2CID 203652784. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ↑ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2021-09-13.

- ↑ "Iron-deficiency anemia". womenshealth.gov. 2017-02-17. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ Jansen, A. J. G.; van Rhenen, D. J.; Steegers, E. a. P.; Duvekot, J. J. (October 2005). "Postpartum hemorrhage and transfusion of blood and blood components". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 60 (10): 663–671. doi:10.1097/01.ogx.0000180909.31293.cf. ISSN 0029-7828. PMID 16186783. S2CID 1910601.

- ↑ Roy, N. B. A.; Pavord, S. (April 2018). "The management of anaemia and haematinic deficiencies in pregnancy and post-partum". Transfusion Medicine (Oxford, England). 28 (2): 107–116. doi:10.1111/tme.12532. ISSN 1365-3148. PMID 29744977. S2CID 13665022.

- ↑ Sifakis, S.; Pharmakides, G. (2006-01-25). "Anemia in Pregnancy". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 900 (1): 125–136. Bibcode:2000NYASA.900..125S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06223.x. PMID 10818399. S2CID 6740558.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Recommendations to Prevent and Control Iron Deficiency in the United States". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-02-01. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ "Anemia and Pregnancy". www.hematology.org. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Achebe, Maureen M.; Gafter-Gvili, Anat (2017-02-23). "How I treat anemia in pregnancy: iron, cobalamin, and folate". Blood. 129 (8): 940–949. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-08-672246. ISSN 1528-0020. PMID 28034892.

- ↑ "Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports. 47 (RR-3): 1–29. 1998-04-03. ISSN 1057-5987. PMID 9563847. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ↑ Juul, Sandra E.; Derman, Richard J.; Auerbach, Michael (2019). "Perinatal Iron Deficiency: Implications for Mothers and Infants". Neonatology. 115 (3): 269–274. doi:10.1159/000495978. ISSN 1661-7819. PMID 30759449.

- ↑ Markova, Veronika; Norgaard, Astrid; Jørgensen, Karsten Juhl; Langhoff-Roos, Jens (2015-08-13). "Treatment for women with postpartum iron deficiency anaemia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (8): CD010861. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010861.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8741208. PMID 26270434.

- ↑ Dahlke, Joshua D.; Mendez-Figueroa, Hector; Maggio, Lindsay; Hauspurg, Alisse K.; Sperling, Jeffrey D.; Chauhan, Suneet P.; Rouse, Dwight J. (July 2015). "Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage: a comparison of 4 national guidelines". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 213 (1): 76.e1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.02.023. ISSN 1097-6868. PMID 25731692.

- ↑ Shaylor, Ruth; Weiniger, Carolyn F.; Austin, Naola; Tzabazis, Alexander; Shander, Aryeh; Goodnough, Lawrence T.; Butwick, Alexander J. (January 2017). "National and International Guidelines for Patient Blood Management in Obstetrics: A Qualitative Review". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 124 (1): 216–232. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001473. ISSN 1526-7598. PMC 5161642. PMID 27557476.

- ↑ "Preconception care to reduce maternal and childhood mortality and morbidity". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ Stephen, Grace; Mgongo, Melina; Hussein Hashim, Tamara; Katanga, Johnson; Stray-Pedersen, Babill; Msuya, Sia Emmanueli (2018-05-02). "Anaemia in Pregnancy: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Adverse Perinatal Outcomes in Northern Tanzania". Anemia. 2018: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2018/1846280. PMC 5954959. PMID 29854446.