Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

| Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | |

|---|---|

| |

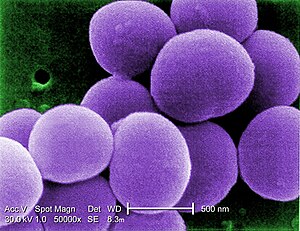

| Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) shows a strain of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria taken from a vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) culture. | |

| Specialty | Microbiology |

| Diagnostic method | Disk diffusion[1] |

| Treatment | Beta-lactam antibiotic (in combination)[2] |

Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) are strains of Staphylococcus aureus that have become resistant to the glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin.[3]

Mechanism of acquired resistance

Strains of hVISA and vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) do not have resistant genes found in Enterococcus and the proposed mechanisms of resistance include the sequential mutations resulting in a thicker cell wall and the synthesis of excess amounts of D-ala-D-ala residues.[4] VRSA strain acquired the vancomycin resistance gene cluster vanA from VRE.[5]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus can be done with disk diffusion(and VA screen plate)[1]

Treatment of infection

For isolates with a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) > 2 µg/mL, an alternative to vancomycin should be used. The approach is to treat with at least one agent to which VISA/VRSA is known to be susceptible by in vitro testing. The agents that are used include daptomycin, linezolid, telavancin, ceftaroline, quinupristin–dalfopristin. For people with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia in the setting of vancomycin failure the IDSA recommends high-dose daptomycin, if the isolate is susceptible, in combination with another agent (e.g. gentamicin, rifampin, linezolid, TMP-SMX, or a beta-lactam antibiotic).[2]

History

Three classes of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus have emerged that differ in vancomycin susceptibilities: vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA), heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (hVISA), and high-level vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA).[6]

Vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA)

Vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) (/ˈviːsə/ or /viːaɪɛseɪ/) was first identified in Japan in 1996[7] and has since been found in hospitals elsewhere in Asia, as well as in the United Kingdom, France, the U.S., and Brazil. It is also termed GISA (glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus), indicating resistance to all glycopeptide antibiotics. These bacterial strains present a thickening of the cell wall, which is believed to reduce the ability of vancomycin to diffuse into the division septum of the cell required for effective vancomycin treatment.[8]

Vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA)

High-level vancomycin resistance in S. aureus has been rarely reported.[9] In vitro and in vivo experiments reported in 1992 demonstrated that vancomycin resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis could be transferred by gene transfer to S. aureus, conferring high-level vancomycin resistance to S. aureus.[10] Until 2002 such a genetic transfer was not reported for wild S. aureus strains. In 2002, a VRSA strain (/ˈvɜːrsə/ or /viːɑːrɛseɪ/) was isolated from a patient in Michigan.[11] The isolate contained the mecA gene for methicillin resistance. Vancomycin MICs of the VRSA isolate were consistent with the VanA phenotype of Enterococcus species, and the presence of the vanA gene was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction. The DNA sequence of the VRSA vanA gene was identical to that of a vancomycin-resistant strain of Enterococcus faecalis recovered from the same catheter tip. The vanA gene was later found to be encoded within a transposon located on a plasmid carried by the VRSA isolate. This transposon, Tn1546, confers vanA-type vancomycin resistance in enterococci.[12]

Heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (hVISA)

The definition of hVISA according to Hiramatsu et al. is a strain of Staphylococcus aureus that gives resistance to vancomycin at a frequency of 10−6 colonies or even higher.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Loomba, Poonam Sood; Taneja, Juhi; Mishra, Bibhabati (2010-01-01). "Methicillin and Vancomycin Resistant S. aureus in Hospitalized Patients". Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 2 (3): 275–283. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.68535. ISSN 0974-777X. PMC 2946685. PMID 20927290.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Liu, Catherine; et al. (2011). "Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the Treatment of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infections in Adults and Children". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 52 (3): e18–e55. doi:10.1093/cid/ciq146. PMID 21208910.

- ↑ "CDC - VISA / VRSA in Healthcare Settings - HAI". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-04-28. Retrieved 2015-06-11.

- ↑ Howden, Benjamin P.; Davies, John K.; Johnson, Paul D. R.; Stinear, Timothy P.; Grayson, M. Lindsay (2010-01-01). "Reduced Vancomycin Susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, Including Vancomycin-Intermediate and Heterogeneous Vancomycin-Intermediate Strains: Resistance Mechanisms, Laboratory Detection, and Clinical Implications". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 23 (1): 99–139. doi:10.1128/CMR.00042-09. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 2806658. PMID 20065327.

- ↑ Chang, Soju; Sievert, Dawn M.; Hageman, Jeffrey C.; Boulton, Matthew L.; Tenover, Fred C.; Downes, Frances Pouch; Shah, Sandip; Rudrik, James T.; Pupp, Guy R. (2003-04-03). "Infection with Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Containing the vanA Resistance Gene". New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (14): 1342–1347. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa025025. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 12672861.

- ↑ Appelbaum PC (November 2007). "Reduced glycopeptide susceptibility in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)". Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 30 (5): 398–408. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.011. PMID 17888634.

- ↑ Hiramatsu, K.; Hanaki, H.; Ino, T.; Yabuta, K.; Oguri, T.; Tenover, F. C. (1997-07-01). "Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 40 (1): 135–136. doi:10.1093/jac/40.1.135. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 9249217.

- ↑ Howden BP, Davies JK, Johnson PD, Stinear TP, Grayson ML (Jan 2010). "Reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, including vancomycin-intermediate and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains: resistance mechanisms, laboratory detection, and clinical implications". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23 (1): 99–139. doi:10.1128/CMR.00042-09. PMC 2806658. PMID 20065327.

- ↑ Gould IM (December 2010). "VRSA-doomsday superbug or damp squib?". Lancet Infect Dis. 10 (12): 816–8. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70259-0. PMID 21109164.

- ↑ Proft, Thomas (2013). Bacterial Toxins: Genetics, Cellular Biology and Practical Applications. Horizon Scientific Press. ISBN 9781908230287. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

- ↑ Amábile-Cuevas, Carlos F. (2007). Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria. Horizon Scientific Press. ISBN 9781904933243.

- ↑ Courvalin P (January 2006). "Vancomycin resistance in gram-positive cocci". Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 Suppl 1: S25–34. doi:10.1086/491711. PMID 16323116.

- ↑ Lu, Yichen; Essex, Max; Roberts, Bryan (2008-04-11). Emerging Infections in Asia. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780387757216.

Further reading

- Chang, Soju; Sievert, Dawn M.; Hageman, Jeffrey C.; Boulton, Matthew L.; Tenover, Fred C.; Downes, Frances Pouch; Shah, Sandip; Rudrik, James T.; Pupp, Guy R. (April 3, 2003). "Infection with Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Containing the vanA Resistance Gene". New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (14): 1342–1347. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa025025. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 12672861.

External links

- PubMed Archived 2018-07-25 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification |

|---|