Ribosomopathy

Ribosomopathies are diseases caused by abnormalities in the structure or function of ribosomal component proteins or rRNA genes, or other genes whose products are involved in ribosome biogenesis.[1][2][3]

Ribosomes

Ribosomes are essential for protein synthesis in all living organisms. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic ribosomes both contain a scaffold of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) on which are arrayed an extensive variety of ribosomal proteins (RP).[4] Ribosomopathies can arise from abnormalities of either rRNA or the various RPs.[citation needed]

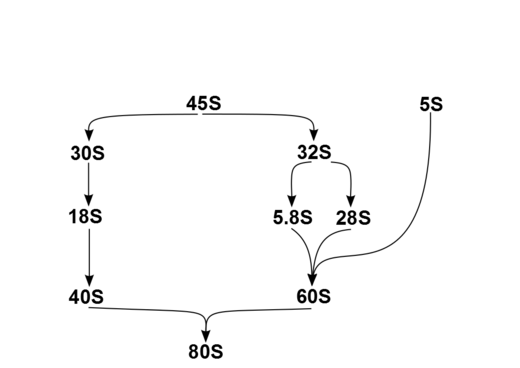

The nomenclature of rRNA subunits is derived from each component's Svedberg unit, which is an ultracentrifuge sedimentation coefficient, that is affected by mass and also shape. These S units of the rRNA subunits cannot simply be added because they represent measures of sedimentation rate rather than of mass. Eukaryotic ribosomes are somewhat larger and more complex than prokaryotic ribosomes. The overall 80S eukaryotic rRNA structure is composed of a large 60S subunit (LSU) and a small 40S subunit (SSU).[5]

In humans, a single transcription unit separated by 2 internally transcribed spacers encodes a precursor, 45S. The precursor 45S rDNA is organized into 5 clusters (each has 30-40 repeats) on chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22. These are transcribed in the nucleolus by RNA polymerase I. 45S is processed in the nucleus via 32S rRNA to 28S[6] and 5.8S,[7] and via 30S to 18S,[8] as shown in the diagram. 18S is a component of the ribosomal 40S subunit. 28S, 5.8S and 5S,[9] which is transcribed independently, are components of 60S. The 5S DNA occurs in tandem arrays (~200-300 true 5S genes and many dispersed pseudogenes); the largest is on chromosome 1q41-42. 5S rRNA is transcribed by RNA polymerase III.[5] It is not fully clear why rRNA is processed in this way rather than being directly transcribed as mature rRNA, but the sequential steps may have a role in the proper folding of rRNA or in subsequent RP assembly.

The products of this processing within the cell nucleus are the four principal types of cytoplasmic rRNA: 28S, 5.8S, 18S, and 5S subunits.[10]: 291 and (cite)(cite) (Mammalian cells also have 2 types of mitochondrial rRNA molecules, 12S and 16S.) In humans, as in most eukaryotes, the 18S rRNA is a component of 40S ribosomal subunit, and the 60S large subunit contains three rRNA species (the 5S, 5.8S and 28S in mammals, 25S in plants). 60S rRNA acts as a ribozyme, catalyzing peptide bond formation, while 40S monitors the complementarity between tRNA anticodon and mRNA.[citation needed]

Diseases

Abnormal ribosome biogenesis is linked to several human genetic diseases.[citation needed]

Ribosomopathy has been linked to skeletal muscle atrophy,[11] and underpins most Diamond–Blackfan anemia (DBA),[2] the X-linked subtype of dyskeratosis congenita (DKCX),[12][13] Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS),[2][14] Shwachman–Diamond syndrome (SDS)[15] and 5q- myelodysplastic syndrome.(5q- MDS),(cite)(cite) North American Indian childhood cirrhosis (NAIC),[16] isolated congenital asplenia (ICAS),[16][17][18][19] and Bowen–Conradi syndrome (BWCNS), CHARGE syndrome[20][21][22][23] and ANE syndrome (ANES).[24]

The associated chromosome, OMIM genotype, phenotype, and possible disruption points are shown:

| name | chromosome | genotype[25] | phenotype | protein | disruption(cite)(cite) |

| DBA1[25] | 19q13.2 | 603474 | 105650 | RPS19 | 30S to 18S[10]: 291 (cite) |

| DBA2 | 8p23-p22 | unknown | 606129 | ||

| DBA3 | 10q22-q23 | 602412 | 610629 | RPS24[26] | 30S to 18S[10]: 291 (cite) |

| DBA4 | 15q | 180472 | 612527 | RPS17[27] | 30S to 18S[10]: 291 |

| DBA5 | 3q29-qter | 180468 | 612528 | RPL35A[28] | 32S to 5.8S/28S[10]: 291 (cite) |

| DBA6 | 1p22.1 | 603634 | 612561 | RPL5[29] | 32S to 5.8S/28S[10]: 291 |

| DBA7 | 1p36.1-p35 | 604175 | 612562 | RPL11[29] | 32S to 5.8S/28S[10]: 291 |

| DBA8 | 2p25 | 603658 | 612563 | RPS7[29] | 30S to 18S[10]: 291 |

| DBA9 | 6p | 603632 | 613308 | RPS10[25] | 30S to 18S[30] |

| DBA10 | 12q | 603701 | 613309 | RPS26 | 30S to 18S[31] |

| DBA11 | 17p13 | 603704 | 614900 | RPS26 | 30S to 18S[31] |

| DBA12 | 3p24 | 604174 | 615550 | RPL15 | 45S to 32S[32] |

| DBA13 | 14q | 603633 | 615909 | RPS29 | |

| DKCX | Xq28 | 300126 | 305000 | dyskerin | associated with both H/ACA small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) and with the RNA component of TERC[33] |

| TCS | |||||

| 5q- | 5q33.1 | 130620 | 153550 | RPS14 | 30S to 18S[10]: 291 |

| SDS | 7q11.21 | 607444 | 260400 | SBDS | 60S to 80S[10]: 291 |

| CHH | 9p13.3 | 157660 | 250250 | RMRP | mitochondrial RNA processing |

| NAIC | 16q22.1 | 607456 | 604901 | cirhin | partial loss of interaction between cirhin and NOL11[34] |

| ICAS | 3p22.1 | 150370 | 271400 | RPSA | |

| BWCNS | 12p13.31 | 611531 | 211180 | EMG1 | 18S to 40S |

| CHARGE | 8q12.1-q12.2; also 7q21.11 | 608892 | 214800 | CHD7; also SEMA3E | |

| ACES | xxx | xxx | RBM28 |

Several ribosomopathies share features such as inherited bone marrow failure, which is characterized a reduced number of blood cells and by a predisposition to cancer.[5] Other features can include skeletal abnormalities and growth retardation.[16] However, clinically these diseases are distinct, and do not show a consistent set of features.[16]

Diamond–Blackfan anemia

With the exception of rare GATA1 genotypes,(cite) Diamond–Blackfan anemia (DBA) arises from a variety of mutations that cause ribosomopathies.[35]

Dyskeratosis congenita

The X-linked subtype of dyskeratosis congenita (DKCX)[citation needed]

Shwachman–Diamond syndrome

Shwachman–Diamond syndrome (SDS) is caused by bi-allelic mutations in the SBDS protein that affects its ability to couple GTP hydrolysis by the GTPase EFL1 to the release of eIF6 from the 60S subunit.[36] Clinically, SDS affects multiple systems, causing bony abnormalities, and pancreatic and neurocognitive dysfunction.[37] SBDS associates with the 60S subunit in human cells and has a role in subunit joining and translational activation in yeast models.[citation needed]

5q- myelodysplastic syndrome

5q- myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)[37] is associated with acquired haplo-insufficiency of RPS14,[37] a component of the eukaryotic small ribosomal subunit (40S).[5] RPS14 is critical for 40S assembly, and depletion of RPS14 in human CD34(+) cells is sufficient to recapitulate the 5q- defect of erythropoiesis with sparing of megakaryocytes.[5]

Treacher Collins syndrome

Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS)

Cartilage–hair hypoplasia

Cartilage–hair hypoplasia (CHH) - some sources list confidently as ribosomopathy, others question[citation needed]

North American Indian childhood cirrhosis

NAIC is an autosomal recessive abnormality of the UTP4 gene, which codes for cirhin. Neonatal jaundice advances over time to biliary cirrhosis with severe liver fibrosis.

Isolated congenital asplenia

Bowen–Conradi syndrome

Bowen–Conradi syndrome (BCS[38] or BWCNS[39]) is an autosomal recessive abnormality of the EMG1 gene, which plays a role in small ribosomal subunit (SSU) assembly.[38][40][41] Most affected children have been from North American Hutterite families, but BWCNS can affect other population groups.[39][42] Skeletal dysmorphology is seen[39][42] and severe prenatal and postnatal growth failure usually leads to death by one year of age.[43]

Other

Familial colorectal cancer type X

Unlike the mutations of the 5 genes associated with DNA mismatch repair, which are associated with Lynch syndrome with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) due to microsatellite instability, familial colorectal cancer (CRC) type X (FCCX) gives rise to HNPCC despite microsatellite stability.[44] FCCX is most likely etiologically heterogeneous but RPS20 may be implicated in some cases.[44]

p53

The p53 pathway is central to the ribosomopathy phenotype.[45] Ribosomal stress triggers activation of the p53 signaling pathway.[46][47]

Cancer

Cancer cells have irregularly shaped, large nucleoli, which may correspond ribosomal gene transcription up-regulation, and hence high cell proliferation. Oncogenes, like c-Myc, can upregulate rDNA transcription in a direct and indirect fashion. Tumor suppressors like Rb and p53, on the other hand, can suppress ribosome biogenesis. Additionally, the nucleolus is an important cellular sensor for stress and plays a key role in the activation of p53.

Ribosomopathy has been linked to the pathology of various malignancies.[45] Several ribosomopathies are associated with an increased rate of cancer. For example, both SDS and 5q- syndrome lead to impaired hematopoiesis and a predisposition to leukemia.[37] Additionally, acquired defects in ribosomal proteins that have not been implicated in congenital ribosomopathies have been found in T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, stomach cancer and ovarian cancer.[3]

References

- ^ Nakhoul H, Ke J, Zhou X, Liao W, Zeng SX, Lu H (2014). "Ribosomopathies: mechanisms of disease". Clin Med Insights Blood Disord. 7: 7–16. doi:10.4137/CMBD.S16952. PMC 4251057. PMID 25512719.

- ^ a b c Narla A, Ebert BL (April 2010). "Ribosomopathies: human disorders of ribosome dysfunction". Blood. 115 (16): 3196–205. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-10-178129. PMC 2858486. PMID 20194897.

- ^ a b De Keersmaecker K, Sulima SO, Dinman JD (February 2015). "Ribosomopathies and the paradox of cellular hypo- to hyperproliferation". Blood. 125 (9): 1377–82. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-10-569616. PMC 4342353. PMID 25575543.

- ^ Ban N, Beckmann R, Cate JH, Dinman JD, Dragon F, Ellis SR, et al. (February 2014). "A new system for naming ribosomal proteins". Curr Opin Struct Biol. 24: 165–9. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2014.01.002. PMC 4358319. PMID 24524803.

- ^ a b c d e Ruggero D, Shimamura A (October 2014). "Marrow failure: a window into ribosome biology". Blood. 124 (18): 2784–92. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-04-526301. PMC 4215310. PMID 25237201.

- ^ "Homo sapiens 28S ribosomal RNA". National Center for Biotechnology Information. 4 February 2017.

- ^ "Homo sapiens 5.8S ribosomal RNA". National Center for Biotechnology Information. 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Homo sapiens 18S ribosomal RNA". National Center for Biotechnology Information. 4 February 2017.

- ^ "Homo sapiens 5S ribosomal RNA". National Center for Biotechnology Information. 3 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hoffbrand AV, Moss PH (2011). Essential Haematology (6th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-9890-5.

- ^ Connolly, Martin (2017). "miR-424-5p reduces ribosomal RNA and protein synthesis in muscle wasting". Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 9 (2): 400–416. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12266. PMC 5879973. PMID 29215200.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM entry 305000: Dyskeratosis congenita, X–linked; DKCX. Johns Hopkins University. [1]

- ^ Stumpf CR, Ruggero D (August 2011). "The cancerous translation apparatus". Curr Opin Genet Dev. 21 (4): 474–83. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2011.03.007. PMC 3481834. PMID 21543223.

- ^ Dauwerse JG, Dixon J, Seland S, Ruivenkamp CA, van Haeringen A, Hoefsloot LH, et al. (January 2011). "Mutations in genes encoding subunits of RNA polymerases I and III cause Treacher Collins syndrome". Nat Genet. 43 (1): 20–2. doi:10.1038/ng.724. PMID 21131976. S2CID 205357102.

- ^ Narla A, Hurst SN, Ebert BL (February 2011). "Ribosome defects in disorders of erythropoiesis". Int J Hematol. 93 (2): 144–149. doi:10.1007/s12185-011-0776-0. PMC 3689295. PMID 21279816.

- ^ a b c d McCann KL, Baserga SJ (August 2013). "Genetics. Mysterious ribosomopathies". Science. 341 (6148): 849–50. doi:10.1126/science.1244156. PMC 3893057. PMID 23970686.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM entry 271400: Asplenia, isolated congenital; ICAS. Johns Hopkins University. [2]

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM entry 150370: Ribosomal protein SA; RPSA. Johns Hopkins University. [3]

- ^ Bolze A, Mahlaoui N, Byun M, Turner B, Trede N, Ellis SR, et al. (May 2013). "Ribosomal protein SA haploinsufficiency in humans with isolated congenital asplenia". Science. 340 (6135): 976–8. Bibcode:2013Sci...340..976B. doi:10.1126/science.1234864. PMC 3677541. PMID 23579497.

- ^ Wong, M. T.; Schölvinck, E. H.; Lambeck, A. J.; Van Ravenswaaij-Arts, C. M. (2015). "CHARGE syndrome: A review of the immunological aspects". European Journal of Human Genetics. 23 (11): 1451–9. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.7. PMC 4613462. PMID 25689927.

- ^ Martin, D. M. (2015). "Epigenetic Developmental Disorders: CHARGE syndrome, a case study". Current Genetic Medicine Reports. 3 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/s40142-014-0059-1. PMC 4325366. PMID 25685640.

- ^ Hsu, P; Ma, A; Wilson, M; Williams, G; Curotta, J; Munns, C. F.; Mehr, S (2014). "CHARGE syndrome: A review". Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 50 (7): 504–11. doi:10.1111/jpc.12497. PMID 24548020.

- ^ Janssen, N; Bergman, J. E.; Swertz, M. A.; Tranebjaerg, L; Lodahl, M; Schoots, J; Hofstra, R. M.; Van Ravenswaaij-Arts, C. M.; Hoefsloot, L. H. (2012). "Mutation update on the CHD7 gene involved in CHARGE syndrome". Human Mutation. 33 (8): 1149–60. doi:10.1002/humu.22086. PMID 22461308. S2CID 36401168.

- ^ 612079

- ^ a b c Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM entry 105650: Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Johns Hopkins University. [4]

- ^ Gazda HT, Grabowska A, Merida-Long LB, Latawiec E, Schneider HE, Lipton JM, et al. (December 2006). "Ribosomal protein S24 gene is mutated in Diamond-Blackfan anemia". Am J Hum Genet. 79 (6): 1110–8. doi:10.1086/510020. PMC 1698708. PMID 17186470.

- ^ Cmejla R, Cmejlova J, Handrkova H, Petrak J, Pospisilova D (December 2007). "Ribosomal protein S17 gene (RPS17) is mutated in Diamond-Blackfan anemia". Hum Mutat. 28 (12): 1178–82. doi:10.1002/humu.20608. PMID 17647292. S2CID 22482024.

- ^ Farrar JE, Nater M, Caywood E, McDevitt MA, Kowalski J, Takemoto CM, et al. (September 2008). "Abnormalities of the large ribosomal subunit protein, Rpl35a, in Diamond-Blackfan anemia". Blood. 112 (5): 1582–92. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-02-140012. PMC 2518874. PMID 18535205.

- ^ a b c Gazda HT, Sheen MR, Vlachos A, Choesmel V, O'Donohue MF, Schneider H, et al. (December 2008). "Ribosomal protein L5 and L11 mutations are associated with cleft palate and abnormal thumbs in Diamond-Blackfan anemia patients". Am J Hum Genet. 83 (6): 769–80. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.004. PMC 2668101. PMID 19061985.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM entry 603632: Ribosomal protein S10; RPS10. Johns Hopkins University. [5]

- ^ a b Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM entry 603701: Ribosomal protein S26; RPS26. Johns Hopkins University. [6]

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM entry 604174: Ribosomal protein L15; RPL15. Johns Hopkins University. [7]

- ^ 300126

- ^ Freed EF, Prieto JL, McCann KL, McStay B, Baserga SJ (2012). "NOL11, implicated in the pathogenesis of North American Indian childhood cirrhosis, is required for pre-rRNA transcription and processing". PLOS Genet. 8 (8): e1002892. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002892. PMC 3420923. PMID 22916032.

- ^ Boria I, Garelli E, Gazda HT, Aspesi A, Quarello P, Pavesi E, et al. (December 2010). "The ribosomal basis of Diamond-Blackfan Anemia: mutation and database update". Hum Mutat. 31 (12): 1269–79. doi:10.1002/humu.21383. PMC 4485435. PMID 20960466.

- ^ Finch AJ, Hilcenko C, Basse N, Drynan LF, Goyenechea B, Menne TF, et al. (May 2011). "Uncoupling of GTP hydrolysis from eIF6 release on the ribosome causes Shwachman-Diamond syndrome". Genes Dev. 25 (9): 917–29. doi:10.1101/gad.623011. PMC 3084026. PMID 21536732.

- ^ a b c d Burwick N, Shimamura A, Liu JM (April 2011). "Non-Diamond Blackfan anemia disorders of ribosome function: Shwachman Diamond syndrome and 5q- syndrome". Semin Hematol. 48 (2): 136–43. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2011.01.002. PMC 3072806. PMID 21435510.

- ^ a b Sondalle SB, Baserga SJ (June 2014). "Human diseases of the SSU processome". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1842 (6): 758–64. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.11.004. PMC 4058823. PMID 24240090.

- ^ a b c Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM entry 211180: XXX. Johns Hopkins University. [8]

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM entry 611531: Essential for mitotic growth 1, S. cervevisiae, Homolog of; EMG1. Johns Hopkins University. [9]

- ^ De Souza RA (February 2010). "Mystery behind Bowen-Conradi syndrome solved: a novel ribosome biogenesis defect". Clin Genet. 77 (2): 116–8. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01304.x. PMID 20096068. S2CID 140113474.

- ^ a b Armistead J, Khatkar S, Meyer B, Mark BL, Patel N, Coghlan G, et al. (June 2009). "Mutation of a gene essential for ribosome biogenesis, EMG1, causes Bowen-Conradi syndrome". Am J Hum Genet. 84 (6): 728–39. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.017. PMC 2694972. PMID 19463982.

- ^ Armistead J, Patel N, Wu X, Hemming R, Chowdhury B, Basra GS, et al. (May 2015). "Growth arrest in the ribosomopathy, Bowen-Conradi syndrome, is due to dramatically reduced cell proliferation and a defect in mitotic progression". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1852 (5): 1029–37. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.02.007. PMID 25708872.

- ^ a b Stoffel EM, Eng C (September 2014). "Exome sequencing in familial colorectal cancer: searching for needles in haystacks". Gastroenterology. 147 (3): 554–6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.031. PMID 25075943.

- ^ a b Raiser DM, Narla A, Ebert BL (March 2014). "The emerging importance of ribosomal dysfunction in the pathogenesis of hematologic disorders". Leuk Lymphoma. 55 (3): 491–500. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.812786. PMID 23863123. S2CID 1259487.

- ^ Zhou X, Liao WJ, Liao JM, Liao P, Lu H (April 2015). "Ribosomal proteins: functions beyond the ribosome". J Mol Cell Biol. 7 (2): 92–104. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjv014. PMC 4481666. PMID 25735597.

- ^ Wang W, Nag S, Zhang X, Wang MH, Wang H, Zhou J, Zhang R (March 2015). "Ribosomal proteins and human diseases: pathogenesis, molecular mechanisms, and therapeutic implications". Med Res Rev. 35 (2): 225–85. doi:10.1002/med.21327. PMC 4710177. PMID 25164622.