Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy

This article needs attention from an expert in Medicine. The specific problem is: "Cause" section is in fairly bad shape with undue weight. (January 2022) |

| Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Prion disease |

| |

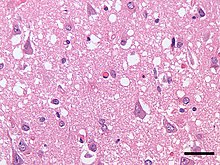

| Micrograph showing spongiform degeneration (vacuoles that appear as holes in tissue sections) in the cerebral cortex of a patient who had died of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. H&E stain, scale bar = 30 microns (0.03 mm). | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | Dementia, seizures, tremors, insomnia, psychosis, delirium, confusion |

| Usual onset | Months to decades |

| Types | Bovine spongiform encephalopathy, Fatal familial insomnia, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, kuru, scrapie, variably protease-sensitive prionopathy, chronic wasting disease, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome, feline spongiform encephalopathy, transmissible mink encephalopathy, exotic ungulate encephalopathy |

| Causes | Prion |

| Risk factors | Contact with infected fluids, ingestion of infected flesh, having one or two parents that have the disease (in case of fatal familial insomnia) |

| Diagnostic method | Currently there is no way to reliably detect prions except at post-mortem |

| Prevention | Varies |

| Treatment | Palliative care |

| Prognosis | Invariably fatal |

| Frequency | Rare |

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) also known as prion diseases,[1] are a group of progressive, incurable, and fatal conditions that are associated with prions and affect the brain and nervous system of many animals, including humans, cattle, and sheep. According to the most widespread hypothesis, they are transmitted by prions, though some other data suggest an involvement of a Spiroplasma infection.[2] Mental and physical abilities deteriorate and many tiny holes appear in the cortex causing it to appear like a sponge when brain tissue obtained at autopsy is examined under a microscope. The disorders cause impairment of brain function, including memory changes, personality changes and problems with movement that worsen chronically.[citation needed]

TSEs of humans include Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome, fatal familial insomnia, and kuru, as well as the recently discovered variably protease-sensitive prionopathy and familial spongiform encephalopathy. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease itself has four main forms, the sporadic (sCJD), the hereditary/familial (fCJD), the iatrogenic (iCJD) and the variant form (vCJD). These conditions form a spectrum of diseases with overlapping signs and symptoms.

TSEs in non-human mammals include scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle – popularly known as "mad cow disease" – and chronic wasting disease (CWD) in deer and elk. The variant form of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in humans is caused by exposure to bovine spongiform encephalopathy prions.[3][4][5]

Unlike other kinds of infectious disease, which are spread by agents with a DNA or RNA genome (such as virus or bacteria), the infectious agent in TSEs is believed to be a prion, thus being composed solely of protein material. Misshapened prion proteins carry the disease between individuals and cause deterioration of the brain. TSEs are unique diseases in that their aetiology may be genetic, sporadic, or infectious via ingestion of infected foodstuffs and via iatrogenic means (e.g., blood transfusion).[6] Most TSEs are sporadic and occur in an animal with no prion protein mutation. Inherited TSE occurs in animals carrying a rare mutant prion allele, which expresses prion proteins that contort by themselves into the disease-causing conformation. Transmission occurs when healthy animals consume tainted tissues from others with the disease. In the 1980s and 1990s, bovine spongiform encephalopathy spread in cattle in an epidemic fashion. This occurred because cattle were fed the processed remains of other cattle, a practice now banned in many countries. In turn, consumption (by humans) of bovine-derived foodstuff which contained prion-contaminated tissues resulted in an outbreak of the variant form of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in the 1990s and 2000s.[7]

Prions cannot be transmitted through the air, through touching, or most other forms of casual contact. However, they may be transmitted through contact with infected tissue, body fluids, or contaminated medical instruments. Normal sterilization procedures such as boiling or irradiating materials fail to render prions non-infective. However, treatment with strong, almost undiluted bleach and/or sodium hydroxide, or heating to a minimum of 134 °C, does destroy prions.[8]

Classification

Differences in shape between the different prion protein forms are poorly understood.

| ICTVdb Code[9] | Disease name | Natural host | Prion name | PrP isoform | Ruminant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-human mammals | |||||

| 90.001.0.01.001. | Scrapie | Sheep and goats | Scrapie prion | PrPSc | Yes |

| 90.001.0.01.002. | Transmissible mink encephalopathy (TME) | Mink | TME prion | PrPTME | No |

| 90.001.0.01.003. | Chronic wasting disease (CWD) | Elk, white-tailed deer, mule deer and red deer | CWD prion | PrPCWD | Yes |

| 90.001.0.01.004. | Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) commonly known as "mad cow disease" |

Cattle | BSE prion | PrPBSE | Yes |

| 90.001.0.01.005. | Feline spongiform encephalopathy (FSE) | Cats | FSE prion | PrPFSE | No |

| 90.001.0.01.006. | Exotic ungulate encephalopathy (EUE) | Nyala and greater kudu | EUE prion | PrPEUE | Yes |

| Camel spongiform encephalopathy (CSE)[10] | Camel | PrPCSE | Yes | ||

| Human diseases | |||||

| 90.001.0.01.007. | Kuru | Humans | Kuru prion | PrPKuru | No |

| 90.001.0.01.008. | Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) | CJD prion | PrPsCJD | No | |

| Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD, nvCJD) | vCJD prion[11] | PrPvCJD | |||

| 90.001.0.01.009. | Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS) | GSS prion | PrPGSS | No | |

| 90.001.0.01.010. | Fatal familial insomnia (FFI) | FFI prion | PrPFFI | No | |

| Familial spongiform encephalopathy[12] | |||||

Features

The degenerative tissue damage caused by human prion diseases (CJD, GSS, and kuru) is characterised by four features: spongiform change (the presence of many small holes), the death of neurons, astrocytosis (abnormal increase in the number of astrocytes due to the destruction of nearby neurons), and amyloid plaque formation. These features are shared with prion diseases in animals, and the recognition of these similarities prompted the first attempts to transmit a human prion disease (kuru) to a primate in 1966, followed by CJD in 1968 and GSS in 1981. These neuropathological features have formed the basis of the histological diagnosis of human prion diseases for many years, although it was recognized that these changes are enormously variable both from case to case and within the central nervous system in individual cases.[13]

The clinical signs in humans vary, but commonly include personality changes, psychiatric problems such as depression, lack of coordination, and/or an unsteady gait (ataxia). Patients also may experience involuntary jerking movements called myoclonus, unusual sensations, insomnia, confusion, or memory problems. In the later stages of the disease, patients have severe mental impairment (dementia) and lose the ability to move or speak.[14]

Early neuropathological reports on human prion diseases suffered from a confusion of nomenclature, in which the significance of the diagnostic feature of spongiform change was occasionally overlooked. The subsequent demonstration that human prion diseases were transmissible reinforced the importance of spongiform change as a diagnostic feature, reflected in the use of the term "spongiform encephalopathy" for this group of disorders.

Prions appear to be most infectious when in direct contact with affected tissues. For example, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease has been transmitted to patients taking injections of growth hormone harvested from human pituitary glands, from cadaver dura allografts and from instruments used for brain surgery (Brown, 2000) (prions can survive the "autoclave" sterilization process used for most surgical instruments). It is also believed[by whom?] that dietary consumption of affected animals can cause prions to accumulate slowly, especially when cannibalism or similar practices allow the proteins to accumulate over more than one generation. An example is kuru, which reached epidemic proportions in the mid-20th century in the Fore people of Papua New Guinea, who used to consume their dead as a funerary ritual.[15] Laws in developed countries now ban the use of rendered ruminant proteins in ruminant feed as a precaution against the spread of prion infection in cattle and other ruminants.[citation needed]

There exists evidence that prion diseases may be transmissible by the airborne route.[16]

Note that not all encephalopathies are caused by prions, as in the cases of PML (caused by the JC virus), CADASIL (caused by abnormal NOTCH3 protein activity), and Krabbe disease (caused by a deficiency of the enzyme galactosylceramidase). Progressive Spongiform Leukoencephalopathy (PSL)—which is a spongiform encephalopathy—is also probably not caused by a prion, although the adulterant that causes it among heroin smokers has not yet been identified.[17][18][19][20] This, combined with the highly variable nature of prion disease pathology, is why a prion disease cannot be diagnosed based solely on a patient's symptoms.

Cause

Genetics

Mutations in the PRNP gene cause prion disease. Familial forms of prion disease are caused by inherited mutations in the PRNP gene. Only a small percentage of all cases of prion disease run in families, however. Most cases of prion disease are sporadic, which means they occur in people without any known risk factors or gene mutations. In rare circumstances, prion diseases also can be transmitted by exposure to prion-contaminated tissues or other biological materials obtained from individuals with prion disease.

The PRNP gene provides the instructions to make a protein called the prion protein (PrP). Under normal circumstances, this protein may be involved in transporting copper into cells. It may also be involved in protecting brain cells and helping them communicate. 24[citation needed] Point-Mutations in this gene cause cells to produce an abnormal form of the prion protein, known as PrPSc. This abnormal protein builds up in the brain and destroys nerve cells, resulting in the signs and symptoms of prion disease.

Familial forms of prion disease are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder. In most cases, an affected person inherits the altered gene from one affected parent.

In some people, familial forms of prion disease are caused by a new mutation in the PRNP gene. Although such people most likely do not have an affected parent, they can pass the genetic change to their children.

Protein-only hypothesis

Protein could be the infectious agent, inducing its own replication by causing conformational change of normal cellular PrPC into PrPSc. Evidence for this hypothesis:

- Infectivity titre correlates with PrPSc levels. However, this is disputed.[21]

- PrPSc is an isomer of PrPC

- Denaturing PrP removes infectivity[22]

- PrP-null mice cannot be infected[23]

- PrPC depletion in the neural system of mice with established neuroinvasive prion infection reverses early spongeosis and behavioural deficits, halts further disease progression and increases life-span[24]

Multi-component hypothesis

While not containing a nucleic acid genome, prions may be composed of more than just a protein. Purified PrPC appears unable to convert to the infectious PrPSc form, unless other components are added, such as RNA and lipids.[25] These other components, termed cofactors, may form part of the infectious prion, or they may serve as catalysts for the replication of a protein-only prion.

Viral hypothesis

This hypothesis postulates that an as of yet undiscovered infectious viral agent is the cause of the disease. Evidence for this hypothesis is as follows:

- Incubation time is comparable to a lentivirus

- Strain variation of different isolates of PrPSc[26]

Diagnosis

There continues to be a very practical problem with diagnosis of prion diseases, including BSE and CJD. They have an incubation period of months to decades during which there are no symptoms, even though the pathway of converting the normal brain PrP protein into the toxic, disease-related PrPSc form has started. At present, there is virtually no way to detect PrPSc reliably except by examining the brain using neuropathological and immunohistochemical methods after death. Accumulation of the abnormally folded PrPSc form of the PrP protein is a characteristic of the disease, but it is present at very low levels in easily accessible body fluids like blood or urine. Researchers have tried to develop methods to measure PrPSc, but there are still no fully accepted methods for use in materials such as blood.[citation needed]

In 2010, a team from New York described detection of PrPSc even when initially present at only one part in a hundred billion (10−11) in brain tissue. The method combines amplification with a novel technology called Surround Optical Fiber Immunoassay (SOFIA) and some specific antibodies against PrPSc. After amplifying and then concentrating any PrPSc, the samples are labelled with a fluorescent dye using an antibody for specificity and then finally loaded into a micro-capillary tube. This tube is placed in a specially constructed apparatus so that it is totally surrounded by optical fibres to capture all light emitted once the dye is excited using a laser. The technique allowed detection of PrPSc after many fewer cycles of conversion than others have achieved, substantially reducing the possibility of artefacts, as well as speeding up the assay. The researchers also tested their method on blood samples from apparently healthy sheep that went on to develop scrapie. The animals' brains were analysed once any symptoms became apparent. The researchers could therefore compare results from brain tissue and blood taken once the animals exhibited symptoms of the diseases, with blood obtained earlier in the animals' lives, and from uninfected animals. The results showed very clearly that PrPSc could be detected in the blood of animals long before the symptoms appeared.[27][28]

Epidemiology

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE) are very rare but can reach epidemic proportions.[clarification needed] It is very hard to map the spread of the disease due to the difficulty of identifying individual strains of the prions. This means that, if animals at one farm begin to show the disease after an outbreak on a nearby farm, it is very difficult to determine whether it is the same strain affecting both herds—suggesting transmission—or if the second outbreak came from a completely different source.

Classic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) was discovered in 1920. It occurs sporadically over the world but is very rare. It affects about one person per million each year. Typically, the cause is unknown for these cases. It has been found to be passed on genetically in some cases. 250 patients contracted the disease through iatrogenic transmission (from use of contaminated surgical equipment).[29] This was before equipment sterilization was required in 1976, and there have been no other iatrogenic cases since then. In order to prevent the spread of infection, the World Health Organization created a guide to tell health care workers what to do when CJD appears and how to dispose of contaminated equipment.[30] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have been keeping surveillance on CJD cases, particularly by looking at death certificate information.[31]

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a prion disease found in North America in deer and elk. The first case was identified as a fatal wasting syndrome in the 1960s. It was then recognized as a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy in 1978. Surveillance studies showed the endemic of CWD in free-ranging deer and elk spread in northeastern Colorado, southeastern Wyoming and western Nebraska. It was also discovered that CWD may have been present in a proportion of free-ranging animals decades before the initial recognition. In the United States, the discovery of CWD raised concerns about the transmission of this prion disease to humans. Many apparent cases of CJD were suspected transmission of CWD, however the evidence was lacking and not convincing.[32]

In the 1980s and 1990s, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or "mad cow disease") spread in cattle at an epidemic rate. The total estimated number of cattle infected was approximately 750,000 between 1980 and 1996. This occurred because the cattle were fed processed remains of other cattle. Then human consumption of these infected cattle caused an outbreak of the human form CJD. There was a dramatic decline in BSE when feeding bans were put in place. On May 20, 2003, the first case of BSE was confirmed in North America. The source could not be clearly identified, but researchers suspect it came from imported BSE-infected cow meat. In the United States, the USDA created safeguards to minimize the risk of BSE exposure to humans.[33]

Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) was discovered in 1996 in England. There is strong evidence to suggest that vCJD was caused by the same prion as bovine spongiform encephalopathy.[34] A total of 231 cases of vCJD have been reported since it was first discovered. These cases have been found in a total of 12 countries with 178 in the United Kingdom, 27 in France, five in Spain, four in Ireland, four in the United States, three in the Netherlands, three in Italy, two in Portugal, two in Canada, and one each in Japan, Saudi Arabia, and Taiwan.[35]

History

In the 5th century BCE, Hippocrates described a disease like TSE in cattle and sheep, which he believed also occurred in man.[36] Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus records cases of a disease with similar characteristics in the 4th and 5th centuries AD.[37] In 1755, an outbreak of scrapie was discussed in the British House of Commons and may have been present in Britain for some time before that.[38] Although there were unsupported claims in 1759 that the disease was contagious, in general it was thought to be due to inbreeding and countermeasures appeared to be successful. Early-20th-century experiments failed to show transmission of scrapie between animals, until extraordinary measures were taken such as the intra-ocular injection of infected nervous tissue. No direct link between scrapie and disease in man was suspected then or has been found since. TSE was first described in man by Alfons Maria Jakob in 1921.[39] Daniel Carleton Gajdusek's discovery that Kuru was transmitted by cannibalism accompanied by the finding of scrapie-like lesions in the brains of Kuru victims strongly suggested an infectious basis to TSE.[40] A paradigm shift to a non-nucleic infectious entity was required when the results were validated with an explanation of how a prion protein might transmit spongiform encephalopathy.[41] Not until 1988 was the neuropathology of spongiform encephalopathy properly described in cows.[42] The alarming amplification of BSE in the British cattle herd heightened fear of transmission to humans and reinforced the belief in the infectious nature of TSE. This was confirmed with the identification of a Kuru-like disease, called new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, in humans exposed to BSE.[43] Although the infectious disease model of TSE has been questioned in favour of a prion transplantation model that explains why cannibalism favours transmission,[44] the search for a viral agent was, as of 2007, being continued in some laboratories.[45][46]

See also

References

- ^ "Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Bastian FO, Sanders DE, Forbes WA, Hagius SD, Walker JV, Henk WG, Enright FM, Elzer PH (2007). "Spiroplasma spp. from transmissible spongiform encephalopathy brains or ticks induce spongiform encephalopathy in ruminants". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 56 (9): 1235–1242. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.47159-0. PMID 17761489.

- ^ "Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2017-04-25. February 2012. Archived from the original on December 20, 2002.

- ^ "Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease > Relationship with BSE (Mad Cow Disease)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2017-04-25. 10 February 2015.

- ^ Collinge, J; Sidle, KC; Meads, J; Ironside, J; Hill, AF (October 24, 1996). "Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of 'new variant' CJD". Nature. 383 (6602): 685–690. Bibcode:1996Natur.383..685C. doi:10.1038/383685a0. PMID 8878476. S2CID 4355186.

- ^ Brown P, Preece M, Brandel JP, Sato T, McShane L, Zerr I, Fletcher A, Will RG, Pocchiari M, Cashman NR, d'Aignaux JH, Cervenakova L, Fradkin J, Schonberger LB, Collins SJ (2000). "Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease at the millennium". Neurology. 55 (8): 1075–81. doi:10.1212/WNL.55.8.1075. PMID 11071481. S2CID 25292433.

- ^ Colle, JG; Bradley, R; Libersky, PP (2006). "Variant CJD (vCJD) and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE): 10 and 20 years on: part 2". Folia Neuropatholica. 44 (2): 102–110. PMID 16823692.

- ^ "Prion Disinfection Options - Biosafety & Occupational Health". University of Minnesota. 17 November 2017.

- ^ "ICTVdB : the universal virus database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses - NLM Catalog - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Deux chercheurs algériens découvrent la maladie du "chameau fou" à Ouargla". 2018-05-09. Archived from the original on 2018-06-17. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

- ^ Believed to be identical to the BSE prion.

- ^ Nitrini R, Rosemberg S, Passos-Bueno MR, da Silva LS, Iughetti P, Papadopoulos M, Carrilho PM, Caramelli P, Albrecht S, Zatz M, LeBlanc A (August 1997). "Familial spongiform encephalopathy associated with a novel prion protein gene mutation". Annals of Neurology. 42 (2): 138–46. doi:10.1002/ana.410420203. PMID 9266722. S2CID 22600579.

- ^ Jeffrey M, Goodbrand IA, Goodsir CM (1995). "Pathology of the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies with special emphasis on ultrastructure". Micron. 26 (3): 277–98. doi:10.1016/0968-4328(95)00004-N. PMID 7788281.

- ^ Collinge J (2001). "Prion diseases of humans and animals: their causes and molecular basis". Annu Rev Neurosci. 24: 519–50. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.519. PMID 11283320.

- ^ Collins S, McLean CA, Masters CL (2001). "Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome, fatal familial insomnia, and kuru: a review of these less common human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies". J Clin Neurosci. 8 (5): 387–97. doi:10.1054/jocn.2001.0919. PMID 11535002. S2CID 31976428.

- ^ Haybaeck, Johannes; Heikenwalder, Mathias; Klevenz, Britta; Schwarz, Petra; Margalith, Ilan; Bridel, Claire; Mertz, Kirsten; Zirdum, Elizabeta; Petsch, Benjamin; Fuchs, Thomas J.; Stitz, Lothar; Aguzzi, Adriano (January 13, 2011). "Aerosols Transmit Prions to Immunocompetent and Immunodeficient Mice". PLOS Pathogens. 7 (1): e1001257. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001257. PMC 3020930. PMID 21249178.

- ^ "hafci.org". Archived from the original on November 1, 2004. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Kriegstein AR; Shungu DC; Millar WS; et al. (1999). "Leukoencephalopathy and raised brain lactate from heroin vapor inhalation ("chasing the dragon")". Neurology. 53 (8): 1765–73. doi:10.1212/WNL.53.8.1765. PMID 10563626. S2CID 2915734.

- ^ Chang YJ, Tsai CH, Chen CJ (1997). "Leukoencephalopathy after inhalation of heroin vapor". J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 96 (9): 758–60. PMID 9308333.

- ^ Koussa S, Zabad R, Rizk T, Tamraz J, Nasnas R, Chemaly R (2002). "[Vacuolar leucoencephalopathy induced by heroin: 4 cases]". Rev. Neurol. (Paris) (in French). 158 (2): 177–82. PMID 11965173.

- ^ Barron RM; Campbell SL; King D; et al. (December 2007). "High titers of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy infectivity associated with extremely low levels of PrPSc in vivo". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (49): 35878–86. doi:10.1074/jbc.M704329200. PMID 17923484.

- ^ Supattapone S; Wille H; Uyechi L; et al. (April 2001). "Branched Polyamines Cure Prion-Infected Neuroblastoma Cells". Journal of Virology. 75 (7): 3453–61. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.7.3453-3461.2001. PMC 114138. PMID 11238871.

- ^ Sakudo A; Lee DC; Saeki K; et al. (August 2003). "Impairment of superoxide dismutase activation by N-terminally truncated prion protein (PrP) in PrP-deficient neuronal cell line". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 308 (3): 660–7. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01459-1. PMID 12914801.

- ^ Mallucci G; Dickinson A; Lineham J; et al. (October 2003). "Depleting Neuronal PrP in Prion Infection Prevents Disease and Reverses Spongiosis". Science. 302 (5646): 871–874. Bibcode:2003Sci...302..871M. doi:10.1126/science.1090187. PMID 14593181. S2CID 13366031.

- ^ Deleault NR, Harris BT, Rees JR, Supattapone S (June 2007). "Formation of native prions from minimal components in vitro". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (23): 9741–6. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.9741D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702662104. PMC 1887554. PMID 17535913.

- ^ Bruce ME (2003). "TSE strain variation". British Medical Bulletin. 66: 99–108. doi:10.1093/bmb/66.1.99. PMID 14522852.

- ^ "Detecting Prions in Blood" (PDF). Microbiology Today.: 195. August 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- ^ "SOFIA: An Assay Platform for Ultrasensitive Detection of PrPSc in Brain and Blood" (PDF). SUNY Downstate Medical Center. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

- ^ "Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies (TSEs), also known as prion diseases | Anses - Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l'alimentation, de l'environnement et du travail". www.anses.fr. 18 February 2013. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ "Infection Control | Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Classic (CJD) | Prion Disease | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ "Surveillance for vCJD | Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Classic (CJD) | Prion Disease | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ Belay and Schonberger (2005). "The Public Health Impact of Prion Diseases" (PDF). Annual Review of Public Health. 26: 206–207. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144536. PMID 15760286.

- ^ Belay and Schonberger (2005). "The Public Health Impact of Prion Diseases" (PDF). Annual Review of Public Health. 26: 198–201. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144536. PMID 15760286.

- ^ "Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on December 20, 2002. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ "Risk for Travelers | Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Classic (CJD) | Prion Disease". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ McAlister, V (June 2005). "Sacred disease of our times: failure of the infectious disease model of spongiform encephalopathy". Clin Invest Med. 28 (3): 101–4. PMID 16021982. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- ^ Digesta Artis Mulomedicinae, Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus

- ^ Brown P, Bradley R; Bradley (December 1998). "1755 and all that: a historical primer of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy". BMJ. 317 (7174): 1688–92. doi:10.1136/bmj.317.7174.1688. PMC 1114482. PMID 9857129.

- ^ Katscher F. (May 1998). "It's Jakob's disease, not Creutzfeldt's". Nature. 393 (6680): 11. Bibcode:1998Natur.393Q..11K. doi:10.1038/29862. PMID 9590681. S2CID 205000018.

- ^ Gajdusek DC (Sep 1977). "Unconventional viruses and the origin and disappearance of kuru". Science. 197 (4307): 943–60. Bibcode:1977Sci...197..943C. doi:10.1126/science.142303. PMID 142303.

- ^ Collins SJ, Lawson VA, Masters CL.; Lawson; Masters (Jan 2004). "Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies". Lancet. 363 (9204): 51–61. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15171-9. PMID 14723996. S2CID 23212525.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hope J, Reekie LJ, Hunter N, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, White H, Scott AC, Stack MJ, Dawson M, Wells GA.; Reekie; Hunter; Multhaup; Beyreuther; White; Scott; Stack; Dawson; et al. (Nov 1988). "Fibrils from brains of cows with new cattle disease contain scrapie-associated protein". Nature. 336 (6197): 390–2. Bibcode:1988Natur.336..390H. doi:10.1038/336390a0. PMID 2904126. S2CID 4351199.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Will RG, Ironside JW, Zeidler M, Cousens SN, Estibeiro K, Alperovitch A, Poser S, Pocchiari M, Hofman A, Smith PG.; Ironside; Zeidler; Cousens; Estibeiro; Alperovitch; Poser; Pocchiari; Hofman; Smith (April 1996). "A new variant of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in the UK". Lancet. 347 (9006): 921–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91412-9. PMID 8598754. S2CID 14230097.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McAlister, V (June 2005). "Sacred disease of our times: failure of the infectious disease model of spongiform encephalopathy". Clin Invest Med. 28 (3): 101–4. PMID 16021982. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- ^ Manuelidis L, Yu ZX, Barquero N, Banquero N, Mullins B; Yu; Banquero; Mullins (February 2007). "Cells infected with scrapie and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease agents produce intracellular 25-nm virus-like particles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (6): 1965–70. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.1965M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610999104. PMC 1794316. PMID 17267596.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Infectious Particles". Manuelidis Lab.

- This entry incorporates public domain text originally from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health [1] and the U.S. National Library of Medicine [2]

External links

- CS1 French-language sources (fr)

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles needing expert attention from January 2022

- All articles needing expert attention

- Medicine articles needing expert attention

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2022

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from April 2012

- Articles needing additional references from April 2018

- All articles needing additional references

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2010

- Wikipedia articles needing clarification from June 2018

- Commons category link from Wikidata

- Articles with Curlie links

- Articles with NKC identifiers

- Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies