Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

| Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: New variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (nvCJD), human mad cow disease | |

| |

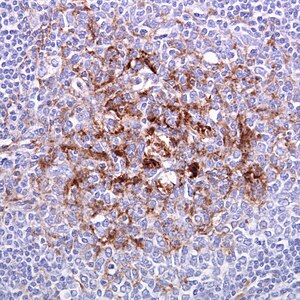

| Biopsy of the tonsil in variant CJD. Prion protein immunostaining. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Psychiatric problems, behavioral changes, painful sensations[1] |

| Usual onset | Less than 30 years old[2] |

| Causes | Prion |

| Risk factors | Eating beef from animals with bovine spongiform encephalopathy[2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Brain biopsy[2] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[4] |

| Prognosis | ~13-month life expectancy[1] |

| Frequency | Fewer than 250 reported cases as of 2012[5] |

Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) is a type of brain disease within the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy family.[5] Symptoms include psychiatric problems, behavioral changes, and painful sensations.[1] The length of time between exposure and the development of symptoms is unclear, but is believed to be years.[2] Average life expectancy following the onset of symptoms is 13 months.[1]

It is caused by prions, which are mis-folded proteins.[6] Spread is believed to be primarily due to eating bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE)-infected beef.[5][6] Infection is also believed to require a specific genetic susceptibility.[3][5] Spread may potentially also occur via blood products or contaminated surgical equipment.[7] Diagnosis is by brain biopsy but can be suspected based on certain other criteria.[2] It is different from classic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, though both are due to prions.[6]

Treatment for vCJD involves supportive care.[4] As of 2012 about 170 cases of vCJD have been recorded in the United Kingdom and 50 cases in the rest of the world.[5] The disease has become less common since 2000.[5] The typical age of onset is less than 30 years old.[2] It was first identified in 1996 by the National CJD Surveillance Unit in Edinburgh, Scotland.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms include psychiatric problems, behavioral changes, and painful sensations.[1] The length of time between exposure and the development of symptoms is unclear, but is believed to be years.[2] Average life expectancy following the onset of symptoms is 13 months.[1]

Cause

Tainted beef

In the UK, the primary cause of vCJD has been eating beef tainted with bovine spongiform encephalopathy.[8] A 2012 study by the Health Protection Agency showed that around 1 in 2,000 people in the UK shows signs of abnormal prion accumulation.[9]

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy occurred due to feeding meat and bone meal to cattle (as a source of protein) caused what was previously an animal pathogen to enter into the human food chain, and from there to begin causing humans to contract vCJD.[10]

Blood products

As of 2018, evidence suggests that while there may be prions in the blood of individuals with vCJD, this is not the case in individuals with sporadic CJD.[8]

In 2004, a report showed that vCJD can be transmitted by blood transfusions.[11] The finding alarmed healthcare officials because a large epidemic of the disease could result in the near future. A blood test for vCJD infection is possible[12] but is not yet available for screening blood donations. Significant restrictions exist to protect the blood supply. The UK government banned anyone who had received a blood transfusion since January 1980 from donating blood.[13] Since 1999 there has been a ban in the UK for using UK blood to manufacture fractional products such as albumin.[14] Whilst these restrictions may go some way to preventing a self-sustaining epidemic of secondary infections the number of infected blood donations is unknown and could be considerable. In June 2013 the government was warned that deaths—then at 176—could rise five-fold through blood transfusions.[15]

On May 28, 2002, the United States Food and Drug Administration instituted a policy that excludes from donation anyone having spent at least six months in certain European countries (or three months in the United Kingdom) from 1980 to 1996. Given the large number of U.S. military personnel and their dependents residing in Europe, it was expected that over 7% of donors would be deferred due to the policy. Later changes to this policy have relaxed the restriction to a cumulative total of five years or more of civilian travel in European countries (six months or more if military). The three-month restriction on travel to the UK, however, has not been changed.[16]

In New Zealand, the New Zealand Blood Service (NZBS) in 2000 introduced measures to preclude permanently donors having resided in the United Kingdom (including the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands) for a total of six months or more between January 1980 and December 1996. The measure resulted in ten percent of New Zealand's active blood donors at the time becoming ineligible to donate blood. In 2003, the NZBS further extended restrictions to permanently preclude donors having received a blood transfusion in the United Kingdom since January 1980, and in April 2006, restrictions were further extended to include the Republic of Ireland and France.[17]

Similar regulations are in place where anyone having spent more than six months for Germany or one year for France living in the UK between January 1980 and December 1996 is permanently banned from donating blood.[18][19]

In Canada, individuals are not eligible to donate blood or plasma if they have spent a cumulative total of three months or more in the UK or France from January 1, 1980 to December 31, 1996. They are also ineligible if they have spent a cumulative total of five years or more in Western Europe outside the UK or France since January 1, 1980 through December 31, 2007 or spent a cumulative total of six months or more in Saudi Arabia from January 1, 1980 through December 31, 1996[20] or if they have had a blood transfusion in the UK, France or Western Europe since 1980.[21]

In Poland, anyone having spent cumulatively six months or longer between 1 January 1980 and 31 December 1996 in the UK, Ireland, or France is permanently barred from donating.[22]

In the Czech Republic, anyone having spent more than six months in the UK or France between the years 1980 and 1996 or received transfusion in the UK after the year 1980 is not allowed to donate blood.[23]

In Finland, anyone having lived or stayed in the British Isles a total of over six months between 1 January 1980 and 31 December 1996 is permanently barred from donating.[24]

Sperm donation

In the U.S., the FDA has banned import of any donor sperm, motivated by a risk of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, inhibiting the once popular[25] import of Scandinavian sperm. Despite this, the scientific consensus is that the risk is negligible, as there is no evidence Creutzfeldt–Jakob is sexually transmitted.[26][27][28]

Other types of brains

Eating other types of brains such as those from squirrels is not recommended due to potential concerns.[29]

Mechanism

Despite the consumption of contaminated beef in the UK being high, vCJD has infected a small number of people. One explanation for this can be found in the genetics of people with the disease. The human PRNP protein which is subverted in prion disease can occur with either methionine or valine at amino acid 129, without any apparent difference in normal function. Of the overall Caucasian population, about 40% have two methionine-containing alleles, 10% have two valine-containing alleles, and the other 50% are heterozygous at this position. Only a single person with vCJD tested was found to be heterozygous; most of those affected had two copies of the methionine-containing form. It is not yet known whether those unaffected are actually immune or only have a longer incubation period until symptoms appear.[30][31]

Diagnosis

Definitive

Examination of brain tissue is required to confirm a diagnosis of variant CJD.[32] The following confirmatory features should be present:[32]

- Numerous widespread kuru-type amyloid plaques surrounded by vacuoles in both the cerebellum and cerebrum – florid plaques.[32]

- Spongiform change and extensive prion protein deposition shown by immunohistochemistry throughout the cerebellum and cerebrum.[32]

Suspected

- Current age or age at death less than 55 years (a brain autopsy is recommended, however, for all physician-diagnosed CJD cases).[32]

- Psychiatric symptoms at illness onset and/or persistent painful sensory symptoms (frank pain and/or dysesthesia).[32]

- Dementia, and development ≥4 months after illness onset of at least two of the following five neurologic signs: poor coordination, myoclonus, chorea, hyperreflexia, or visual signs. (If persistent painful sensory symptoms exist, ≥4 months' delay in the development of the neurologic signs is not required).[32]

- A normal or an abnormal EEG, but not the diagnostic EEG changes often seen in classic CJD.[32]

- Duration of illness of over 6 months.[32]

- Routine investigations do not suggest an alternative, non-CJD diagnosis.[32]

- No history of getting human pituitary growth hormone or a dura mater graft from a cadaver.[32]

- No history of CJD in a first degree relative or prion protein gene mutation in the person.[32]

Classification

vCJD is a separate condition from classic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (though both are caused by PrP prions).[6] Both classic and variant CJD are subtypes of Creutzfeld–Jakob disease. There are three main categories of CJD disease: sporadic CJD, hereditary CJD, and acquired CJD, with variant CJD being in the acquired group along with iatrogenic CJD.[33][34] The classic form includes sporadic and hereditary forms.[35] Sporadic CJD is the most common type.[36]

ICD-10 has no separate code for vCJD and such cases are reported under the Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease code (A81.0).[37]

Epidemiology

The Lancet in 2006 suggested that it may take more than 50 years for vCJD to develop, from their studies of kuru, a similar disease in Papua New Guinea.[38] The reasoning behind the claim is that kuru was possibly transmitted through cannibalism in Papua New Guinea when family members would eat the body of a dead relative as a sign of mourning. In the 1950s, cannibalism was banned in Papua New Guinea.[39] In the late 20th century, however, kuru reached epidemic proportions in certain Papua New Guinean communities, therefore suggesting that vCJD may also have a similar incubation period of 20 to 50 years. A critique to this theory is that while mortuary cannibalism was banned in Papua New Guinea in the 1950s, that does not necessarily mean that the practice ended. Fifteen years later Jared Diamond was informed by Papuans that the practice continued.[39] Kuru may have passed to the Fore people through the preparation of the dead body for burial.

These researchers noticed a genetic variation in some people with kuru that has been known to promote long incubation periods. They have also proposed that individuals having contracted CJD in the early 1990s represent a distinct genetic subpopulation, with unusually short incubation periods for bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). This means that there may be many more people with vCJD with longer incubation periods, which may surface many years later.[38]

Prion protein is detectable in lymphoid and appendix tissue up to two years before the onset of neurological symptoms in vCJD. Large scale studies in the UK have yielded an estimated prevalence of 493 per million, higher than the actual number of reported cases. This finding indicates a large number of asymptomatic cases and the need to monitor.[40]

Society and culture

In 1997, a number of people from Kentucky developed vCJD. It was discovered that all had consumed squirrel brains, although a coincidental relationship between the disease and this dietary practice may have been involved.[41] In 2008, UK scientists expressed concern over the possibility of a second wave of human cases due to the wide exposure and long incubation of some cases of vCJD.[42] In 2015, a man from New York developed vCJD after eating squirrel brains. From November 2017 to April 2018, four suspected cases of the disease arose in Rochester.[43]

United Kingdom

Researchers believe one in 2,000 people in the UK is a carrier of the disease linked to eating contaminated beef (vCJD).[44] The survey provides the most robust prevalence measure to date—and identifies abnormal prion protein across a wider age group than found previously and in all genotypes, indicating "infection" may be relatively common. This new study examined over 32,000 anonymous appendix samples. Of these, 16 samples were positive for abnormal prion protein, indicating an overall prevalence of 493 per million population, or one in 2,000 people are likely to be carriers. No difference was seen in different birth cohorts (1941–1960 and 1961–1985), in both sexes, and there was no apparent difference in abnormal prion prevalence in three broad geographical areas. Genetic testing of the 16 positive samples revealed a higher proportion of valine homozygous (VV) genotype on the codon 129 of the gene encoding the prion protein (PRNP) compared with the general UK population. This also differs from the 176 people with vCJD, all of whom to date have been methionine homozygous (MM) genotype. The concern is that individuals with this VV genotype may be susceptible to developing the condition over longer incubation periods.[45]

Human BSE foundation

In 2000 a voluntary support group was formed by families who had lost someone to vCJD. The goal was to support other families going through a similar experience. This support was provided through a National Helpline, a Carer's Guide, a website and a network of family befriending. The support groups had an internet presence at the turn of the 21st century. The driving force behind the foundation was Lester Firkins, who lost his own young son to the disease.[46][47]

In October 2000 the report of the government inquiry into BSE chaired by Lord Phillips was published.[48] The BSE report criticised former Conservative Party Agriculture Ministers John Gummer, John MacGregor and Douglas Hogg.[49] The report concluded that the escalation of BSE into a crisis was the result of intensive farming, particularly with herbivore cows being fed with cow and sheep remains. Furthermore, the report was critical of the way the crisis had been handled.[50] There was a reluctance to consider the possibility that BSE could cross the species barrier was proving increasingly uncertain. The government assured the public that British beef was safe to eat, with agriculture minister John Gummer famously feeding his daughter a beefburger. The British government were reactive more than proactive in response; the worldwide ban on all British beef exports in March 1996 was a serious economic blow.[51]

The foundation had been calling for compensation to include a care package to help relatives look after those with vCJD. There have been widespread complaints of inadequate health and social services support.[52] Following the Phillips Report in October 2001, the government announced a compensation scheme for British people affected with vCJD. The multi-million-pound financial package was overseen by the vCJD Trust.

A memorial plaque for persons who have died due to vCJD was installed in central London.[when?] It is located on the boundary wall of St Thomas' Hospital in Lambeth facing the Riverside Walk of Albert Embankment.[53]

See also

- Jonathan Simms, a person who died from vCJD

- Mepacrine

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics | Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Classic (CJD)". CDC. 10 February 2015. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Classic CJD versus Variant CJD". CDC. 11 February 2015. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ironside, JW (Jul 2010). "Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease". Haemophilia. 16 Suppl 5: 175–80. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02317.x. PMID 20590878.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Treatment Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease". CDC. 10 February 2015. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Ironside, JW (2012). "Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: an update". Folia Neuropathologica. 50 (1): 50–6. PMID 22505363.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "About vCJD". CDC. 10 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ↑ Ferri, Fred F. (2017). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 343. ISBN 9780323529570. Archived from the original on 2020-02-04. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Fact Sheet | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". NINDS. March 2003. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ HPA Press Office (August 10, 2012). "Summary results of the second national survey of abnormal prion prevalence in archived appendix specimens". Archived from the original on March 25, 2013.

- ↑ D. Quick, Jonathan; Bronwyn Fryer (2018). The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop it. St. Martin's Press. pp. 51–53. Archived from the original on 2020-07-08. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- ↑ Peden AH, Head MW, Ritchie DL, Bell JE, Ironside JW (2004). "Preclinical vCJD after blood transfusion in a PRNP codon 129 heterozygous patient". The Lancet. 364 (9433): 527–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16811-6. PMID 15302196.

- ↑ Edgeworth, JA; Farmer, M; Sicilia, A; Tavares, P; Beck, J; Campbell, T; Lowe, J; Mead, S; Rudge, P; Collinge, J; Jackson, GS (Feb 5, 2011). "Detection of prion infection in variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: a blood-based assay". The Lancet. 377 (9764): 487–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62308-2. PMID 21295339.

- ↑ "Variant CJD and blood donation" (PDF). National Blood Service. August 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ Regan F, Taylor C (July 2002). "Blood transfusion medicine". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 325 (7356): 143–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7356.143. PMC 1123672. PMID 12130612.

- ↑ Rowena Mason (April 28, 2013). "Mad cow infected blood 'to kill 1,000'". Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ↑ "In-Depth Discussion of Variant Creutzfeld–Jacob Disease and Blood Donation". American Red Cross. Archived from the original on 2007-12-30. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ "CJD (Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease) - Information for blood donors" (PDF). New Zealand Blood Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ "Permanent exclusion criteria" (in German). Blutspendedienst Hamburg. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) English via Google Translate - ↑ "Les contre-indications au don de sang". Etablissement français du sang. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ↑ "Canada restricts blood donors from Saudi Arabia". ctv news. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Travel restrication". Canadian Blood Services. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Permanent exclusion criteria / Dyskwalifikacja stała" (in Polish). RCKiK Warszawa. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "Blood donor guidance / Poučení dárce krve" (in Czech). Fakultní nemocnice Královské Vinohrady. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "www.veripalvelu.fi". www.bloodservice.fi. Archived from the original on 2020-03-10. Retrieved 2020-01-10.

- ↑ Stein, Rob (13 August 2008). "Mad Cow Rules Hit Sperm Banks' Patrons". washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post Company. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ↑ Kotler, Steven (27 September 2007). "The God of Sperm". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on 6 July 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ↑ Mortimer, D.; Barratt, CLR (2006). "Is there a real risk of transmitting variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease by donor sperm insemination?". Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 13 (6): 778–790. doi:10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61024-3.

- ↑ Lapidos, Juliet (26 September 2007). "Is Mad Cow an STD?". Slate. Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ↑ Blakeslee, Sandra (29 August 1997). "Kentucky Doctors Warn Against a Regional Dish: Squirrels' Brains". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ↑ Saba, R; Booth, SA (2013). "The genetics of susceptibility to variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease". Public Health Genomics. 16 (1–2): 17–24. doi:10.1159/000345203. PMID 23548713. Archived from the original on 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

- ↑ Sikorska, B; Liberski, PP (2012). Human prion diseases: from Kuru to variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Sub-cellular Biochemistry. Subcellular Biochemistry. Vol. 65. pp. 457–96. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5416-4_17. ISBN 978-94-007-5415-7. PMID 23225013.

- ↑ 32.00 32.01 32.02 32.03 32.04 32.05 32.06 32.07 32.08 32.09 32.10 32.11 "Diagnostic Criteria | Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Classic (CJD)". CDC. 10 February 2015. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ↑ "Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ↑ Geschwind, MD (December 2015). "Prion Diseases". Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 21 (6): 1612–1638. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000251. PMC 4879966. PMID 26633779.

- ↑ "About CJD | Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Classic (CJD)". CDC. 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ↑ Geschwind, MD (December 2015). "Prion Diseases". Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 21 (6 Neuroinfectious Disease): 1612–38. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000251. PMC 4879966. PMID 26633779.

- ↑ "International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10)-WHO Version for 2016 — A81.0". World Health Organization. 2016. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Collinge J, Whitfield J, McKintosh E (June 2006). "Kuru in the 21st century – an acquired human prion disease with very long incubation periods". Lancet. 367 (9528): 2068–74. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68930-7. PMID 16798390.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Diamond, JM (7 September 2000). "Archaeology: Talk of cannibalism". Nature. 407 (25–26): 25–26. doi:10.1038/35024175. PMID 10993054.

- ↑ Diack, Abigail B; Head, Mark W; McCutcheon, Sandra; Boyle, Aileen; Knight, Richard; Ironside, James W; Manson, Jean C; Will, Robert G (1 November 2014). "Variant CJD". Prion. 8 (4): 286–95. doi:10.4161/pri.29237. ISSN 1933-6896. PMC 4601215. PMID 25495404.

- ↑ Berger JR, Waisman E, Weisman B (August 1997). "Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and eating squirrel brains". Lancet. 350 (9078): 642. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63333-8. PMID 9288058.

- ↑ "Warning over second wave of CJD cases". The Observer. 8 August 2008. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ↑ "Man Dies from Extremely Rare Disease After Eating Squirrel Brains". Live Science. Archived from the original on 2018-10-18. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- ↑ "Estimate doubled for vCJD carriers in UK". BBC News. 2013-10-15. Archived from the original on 2014-02-10.

- ↑ Gill, Noel (2013). "Prevalent abnormal prion protein in human appendixes after bovine spongiform encephalopathy epizootic: large scale survey". British Medical Journal. 347: f5675. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5675. PMC 3805509. PMID 24129059.

- ↑ "Pioneer profile: Lester Firkin" (PDF). The Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2009-03-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ↑ "James Lind Alliance Affiliates Newsletter" (PDF). James Lind Alliance. 2012-01-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-03-31. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ↑ "BSE crisis: Timeline". The Guardian. London. 2019-10-26. Archived from the original on 2017-03-12. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- ↑ "From nannyism to public disclosure: the BSE Inquiry report". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 164 (2): 165. 23 Jan 2001. PMC 80663. PMID 11332300.

- ↑ "The BSE Inquiry Report". The Health Foundation. 2000-10-01. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Ainsworth, Claire; Carrington, Damian (2019-10-25). "BSE disaster: the history". New Scientist. London. Archived from the original on 2020-05-27. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- ↑ "BSE victims to get millions". The Guardian. 22 October 2000. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ↑ "memorial should be moved from listed wall, say Lambeth planners". London SE1 community website. 23 January 2016. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.