Nodding disease

| Nodding disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Nodding syndrome | |

| |

| Map of counties of South Sudan affected by nodding disease. Several of these are in the Central Equatoria state, in the south of the country near the border with Uganda; Juba on the White Nile is the nation's capital. The red district was already affected in 2001, in yellow districts the disease was prevalent as of 2011 and in green districts there are only sporadic reports.[1] | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Nodding disease is a disease which emerged in Sudan in the 1960s.[2] It is a mentally and physically disabling disease that only affects children, typically between the ages of 5 and 15. It is currently restricted to small regions in South Sudan, Tanzania, and northern Uganda.[3][4] Prior to the South Sudan outbreaks and subsequent limited spread, the disease was first described in 1962 existing in secluded mountainous regions of Tanzania,[5] although the connection between that disease and nodding syndrome was only made recently.[4]

Signs and symptoms

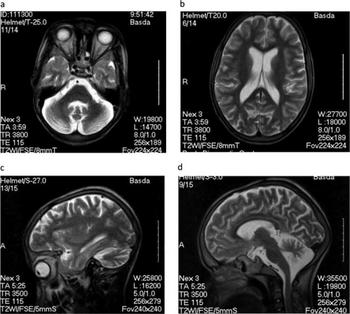

Children affected by nodding disease experience a complete and permanent stunting of growth. The growth of the brain is also stunted, leading to mental handicap. The disease is named for the characteristic, pathological nodding seizure, which often begins when the children begin to eat, or sometimes when they feel cold.[6] These seizures are brief and halt after the children stop eating or when they feel warm again. Seizures in nodding disease span a wide range of severity. Neurotoxicologist Peter Spencer, who has investigated the disease, has stated that upon presentation with food, "one or two [children] will start nodding very rapidly in a continuous, pendulous nod. A nearby child may suddenly go into a tonic–clonic seizure, while others will freeze."[7] Severe seizures can cause the child to collapse, leading to further injury.[8] Sub-clinical seizures have been identified in electroencephalograms, and MRI scans have shown brain atrophy and damage to the hippocampus and glia cells.[5]

It has been found that no seizures occur when victims are given an unfamiliar or non-traditional food, such as chocolate.[9]

Causes

It is currently not known what causes the disease, but it is believed to be connected to infestations of the parasitic worm Onchocerca volvulus, which is prevalent in all outbreak areas,[10] and a possible explanation involves the formation of antibodies against parasite antigen that are cross-reactive to leiomodin-1 in the hippocampus.[11] O. volvulus, a nematode, is carried by the black fly and causes river blindness. In 2004, most children suffering from nodding disease lived close to the Yei River, a hotbed for river blindness, and 93.7% of nodding disease sufferers were found to harbour the parasite — a far higher percentage than in children without the disease.[12] A link between river blindness and normal cases of epilepsy,[13] as well as retarded growth,[14] had been proposed previously, although the evidence for this link is inconclusive.[15] Of the connection between the worm and the disease, Scott Dowell, the lead investigator into the syndrome for the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), stated: "We know that [Onchocerca volvulus] is involved in some way, but it is a little puzzling because [the worm] is fairly common in areas that do not have nodding disease".[10] Andrea Winkler, the first author of a 2008 Tanzanian study, has said of the connection: "We could not establish any hint that Onchocerca volvulus is actually going into the brain, but what we cannot exclude is that there is an autoimmune mechanism going on."[5] In the most severely affected region of Uganda, infection with microfilariae in epileptic or nodding children ranged from 70% to 100%.[16]

The CDC is investigating a possible connection with wartime chemical exposure. The team is also investigating whether a deficiency in vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) could be a cause, noting the seizures of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy and this common deficiency in disease sufferers.[5] Older theories include a 2002 toxicology report that postulated a connection with tainted monkey meat, as well as the eating of agricultural seeds provided by relief agencies that were covered in toxic chemicals.[6]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is not very advanced and is based on the telltale nodding seizures of the victims. When stunted growth and mental disability are also present, probability of nodding syndrome is high. In the future, neurological scans may also be used in diagnosis.[17]

Management

As there is no known cure for the disease, treatment has been directed at symptoms, and has included the use of anticonvulsants such as sodium valproate[10] and phenobarbitol. Anti-malaria drugs have also been administered, to unknown effect.[7] Nutritional deficiencies may also be present.

Prognosis

Nodding syndrome is debilitating both physically and mentally. In 2004, Peter Spencer stated: "It is, by all reports, a progressive disorder and a fatal disorder, perhaps with a duration of about three years or more."[7] While a few children are said to have recovered from it, many have died from the illness.[6] Seizures can also cause children to collapse, potentially causing injury or death.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

While the majority of occurrences of the disease known as "nodding syndrome" have been relatively recent, it appears that the condition was first documented in 1962 in southern Tanzania.[5] More recently, nodding syndrome had become most prevalent in South Sudan, where in 2003 approximately 300 cases were found in Mundri alone. By 2009, it had spread across the border to Uganda's Kitgum district,[3] and the Ugandan ministry of health declared that more than 2000 children had the disease.[5] As of the end of 2011, outbreaks were concentrated in Kitgum, Pader and Gulu. More than 1000 cases were diagnosed in the last half of that year.[10]

There were further outbreaks in early 2012, in South Sudan, Uganda, and Tanzania.[18]

The spread and manifestation of outbreaks may further be exacerbated due to the poor availability of health care in the region.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Meredith Wadman (13 July 2011). "Box: A growing threat". Nature. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ↑ Lacey M (2003). "Nodding disease: mystery of southern Sudan". Lancet Neurology. 2 (12): 714. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00599-4. PMID 14649236. S2CID 12387559.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 UGANDA: Nodding disease or "river epilepsy"? Archived 2011-06-11 at the Wayback Machine IRIN Africa. Accessed 19 October 2010

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Nodding disease in East Africa". CNN. Archived from the original on 31 August 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Wadman, Meredith (13 July 2011). "African outbreak stumps experts". Nature. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 'Nodding disease' hits Sudan Archived 2021-06-09 at the Wayback Machine Andrew Harding BBC News 23 September 2003, Accessed 19 October 2007

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Ross, Emma (3 February 2004). "Sudan A Hotbed Of Exotic Diseases". CBS News. Rumbek, Sudan. Archived from the original on February 18, 2004. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ↑ Bizarre Illness Terrifies Sudanese - 'Nodding Disease' Victims Suffer Seizures, Retardation, Death Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine Emma Ross, CBS News, Jan. 28, 2004. Accessed 19 October 2007

- ↑ "WHO document describing disease with unusual observation re: unfamiliar food". World Health Organisation. WHO. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Abraham, Curtis (23 December 2011). "Mysterious nodding syndrome spreading through Uganda". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ↑ Johnson, Tory P.; Tyagi, Richa; Lee, Paul R.; Lee, Myoung-Hwa; Johnson, Kory R.; Kowalak, Jeffrey; Elkahloun, Abdel; Medynets, Marie; Hategan, Alina (2017-02-15). "Nodding syndrome may be an autoimmune reaction to the parasitic worm Onchocerca volvulus". Science Translational Medicine. 9 (377): eaaf6953. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6953. ISSN 1946-6234. PMC 5434766. PMID 28202777.

- ↑ When Nodding Means Dying: A baffling new epidemic is sweeping Sudan. Lekshmi Santhosh The Yale Journal of Public Health Vol. 1, No. 1, 2004. Accessed 25 December 2011

- ↑ Druet-Cabanac M, Boussinesq M, Dongmo L, Farnarier G, Bouteille B, Preux PM (2004). "Review of epidemiological studies searching for a relationship between onchocerciasis and epilepsy". Neuroepidemiology. 23 (3): 144–9. doi:10.1159/000075958. PMID 15084784. S2CID 10903855.

- ↑ Ovuga E, Kipp W, Mungherera M, Kasoro S (1992). "Epilepsy and retarded growth in a hyperendemic focus of onchocerciasis in rural western Uganda". East African Medical Journal. 69 (10): 554–6. PMID 1473507.

- ↑ Marin B, Boussinesq M, Druet-Cabanac M, Kamgno J, Bouteille B, Preux PM (2006). "Onchocerciasis-related epilepsy? Prospects at a time of uncertainty". Trends Parasitol. 22 (1): 17–20. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2005.11.006. PMID 16307906.

- ↑ Dan Michael Komakech (2011-11-07). "Nodding disease community dialogue meeting held in Pader district". Acholi Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-30. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ↑ "CDC - Global Health - Nodding Syndrome". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ "East African Mystery Disease: Nodding Syndrome". Daily Kos. March 14, 2012. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

External links

- McKenzie, David (19 March 2012). "Mysterious disease devastating families" (2 min 44 sec video report). CNN. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- Pages with script errors

- Webarchive template wayback links

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles using infobox templates with no data rows

- Ailments of unknown cause

- Health in Africa

- Health in Sudan

- Rare diseases

- Syndromes