Women during the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera

| Part of a series on |

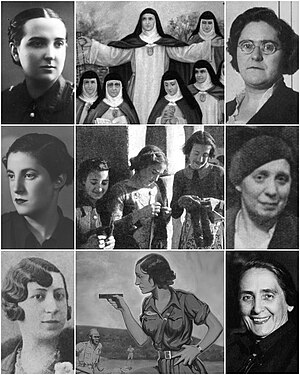

| Women in the Spanish Civil War |

|---|

|

|

|

Women during the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera had few rights and were subjected to discriminatory gender norms. While feminists were active, they were limited in numbers and their organizations were not overly successful in accomplishing their goals.

Women's suffrage took limited steps forward. 8 March 1924 Royal Decree's Municipal Statue Article 51 gave women the right to vote for the first time, but was viewed as an attempt to shore up Primo de Rivera's electoral chances. By the time of the next national elections, the constitution giving women the right to vote was no longer in force as a new constitution was being drafted.

The second part of the Dictatorship would see an increase in women's agitation for equal rights. It also saw some women falling out with traditional political organizations, seeing them as not being effective for their goals. Educational opportunities for women would increase, along with literacy rates for women.

Women on the street often faced harassment. Economic requirements meant women were more visible in the workforce, and started encroaching on traditional male domains like the cafe and ateneo.

Background

The Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera started in 1923 and continued until 1929.[1] It took place during the Bourbon Restoration, during the wider reign of Alfonso XIII.[2] The abdication of king of Spain in 1930 would spell the end of the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera, and usher in the era of the Second Republic, with its end resulting in elections being called for June 1931.[1][3]

Military directorate (1923-1925)

Feminists

The dictatorship of Primo de Rivera saw few feminist events in Spain. When they did organize, men viewed their activities as a joke. Feminine independence, principally organized in Madrid around the Lyceum Club, was condemned by members of the Catholic Church and viewed as scandalous in nature. It was viewed by some men as threatening to the status quo.[4] Feminists in the dictatorship period were often focused on restrained but determined efforts to be nonconformist in their approach to womenhood. Most of their activity was devoted towards creating fictional works as a form of social criticism.[4] Other feminist organizations also existed by 1920, though they were much less visible and successful in their goals. They included the Future and Feminine Progressive in Barcelona, the Concepción Arenal Society in Valencia and Feminine Social Action Group in Madrid. Most members came from middle-class backgrounds, and consequently did not represent the broader spectrum of women in Spain.[4]

Women's suffrage

The 8 March 1924 Royal Decree's Municipal Statue Article 51 for the first time included an appendix which would allow electoral authorities on a municipal level to list women over the age of 23 who were not controlled by male guardians or the state to be counted. Article 84.3 said unmarried women could vote in municipal elections assuming they were the head of household, over the age of 23, not prostitutes and their status did not change. Changes were made the following month that allowed women who met those some qualifications to run for political office. Consequently, some women took advantage of this political opening, ran for office and won some seats in municipal governments as councilors and mayors where elections were held.[5][6][7] This was a surprise move by Primo de Rivera in giving women the right to vote, and was largely viewed as a way of shoring up his electoral base ahead of scheduled elections in the following year. This brief period saw many political parties try to capture the women's vote before the elections were eventually cancelled.[7][6] Manuel Cordero of El Socialista of wrote in June 1924 of a right wing governing supporting "the feminine vote supposes a revolutionary act and it seems strange that it is a reactionary which who has projected this reform in Spain."[7]

María Cambrils was pleased with women being given the right to vote, but balked at the restrictions placed upon female voters.[8] PSOE's leader Andrés Saborit also supported this claiming that socialism needed to expand how it discussed women as transformational agents in society, and not allow the Catholic Church to monopolize how women were defined inside Spanish culture.[8]

Some Catholics tried to capitalize on this for their own political interests, achieving success when local elections in some places saw 40% of their total votes come from women.[9] By the time of the next national elections, the constitution giving women the right to vote was no longer in force as a new constitution was being drafted.[6][9] The arguments made around the 1924 Royal Decree would later play a critical role in the debates around women's suffrage in the Second Republic.[9]

Political activity and government participation

When political activity occurred by women in the pre-Republican period, it was often spontaneous. They were also often ignored by left-wing male political leaders. Despite this, these riots and protests represented increasing political awareness among women of their need to be more active in social and political spheres to enact change to improve their lives.[10]

Middle-class women in urban areas, freed from earlier labor in the home, began to start to lobby for changes to improve their own lives. This included things like changes to divorce laws, better education and equal pay.[11] When politicians were faced with these demands, they often labeled them "women's issues."[11] No serious reforms were able to be manifested under the Primo de Rivera dictatorship.[11]

Agrupación Femenina Socialista de Madrid were active during this period. Trying to engage more broadly, they invited three Madrid based women lawyers, Victoria Kent, Clara Campoamor and Matilde Huici, to speak at Casa del Pueblo to better understand women's demands during the period in 1925 and 1926. By 19 March 1926, Campoamor had withdrawn her assistance to Socialists working on women's issues.[8] Nelken would say in 1922 that she saw both Socialists and the Catholics as offering little hope for women, as neither was capable of seeing the problems faced by women. This issue was one she saw as the central failing of feminism, a position that demonstrated a massive rift in Spanish feminism in the Primo de Rivera period.[8]

Socialists

Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE)

During the 1920s and early 1930s, women became more involved with socialist movements. This did not translate to participation in the political side, as socialist political organizations were openly hostile to women and not interested in attracting their involvement.[10] When women did create socialist organizations, they were auxiliary organizations to male dominated ones. This was the case for Group of Feminist Socialists of Madrid and Feminist Socialist Groups. This differed from anarchists, with socialist women playing much more passive roles than their anarchist peers. As a consequence, when the Civil War came, few socialist women headed to the front lines.[10][4]

| PSOE members of the Congress of Deputies | |||||

| Election | Seats | Vote | % | Status | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 | 7 / 409

|

Opposition | Pablo Iglesias Posse | ||

Civil Directorate (1925-1930)

During the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera's had no real national congress until the creation of the Asamblea Nacional Consultiva in 1927. Despite representing various factions across Spain by based on appointment, the body had very little power. A quota system drawn from 18 different regions of Spain, representing different political parties, determined who sat in the body. The last Asamblea Nacional Consultiva group had a representation of only 3% women. Some of the women who sat in the body were wives of nobility, who often did not take their role seriously. Some were drawn from wider society because of their contribution in culture and the arts. Their appointments were a desire to see women become more involved in political life.[12][13]

PSOE and UGT both had internal divisions over whether to participate in the assembly as it lacked real powers. After much internal debate, both refused to participate. Consequently, the government appointed socialists to the assembly without any party or union oversight.[13] María Cambrils would be one of these socialist women to serve in the 1927 Assembly.[8]

Women's suffrage and political activity

Women gained access to national representation during the 1927–1929 legislative period as a result of the Decree of 12 September 1927. Its Article 15 stated: "to it may belong, without distinction, men and women, single, widowed or married, these duly authorized by their husbands and as long as they do not belong to the Assembly [...]. Its designation will be made nominally and by order of the Presidency, agreed in the Council of Ministers before October 6 next."[14][15][6]

The 1927–1929 session also began the process of drafting a new Spanish constitution that would have fully franchised women voters in Article 55. The article was not approved. Despite this, women were eligible to serve in the National Assembly in the Palacio de las Cortes, and 15 women were appointed to seats on 10 October 1927. Thirteen were members of the National Life Activities Representatives (Spanish: Representantes de Actividades de la Vida Nacional). Another two were State Representatives (Spanish: Representantes del Estado). These women included María de Maeztu, Micaela Díaz Rabaneda and Concepción Loring Heredia. During the Congreso de los Diputados's inaugural session in 1927, the President of the Assembly specifically welcomed the new women, claiming their exclusion had been unjust.[14][15] Loring Heredia would interrupt and demand an explanation from the Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts on 23 November 1927, marking the first time a woman had done this on the floor of Congress.[16][15]

Spain's right was divided into several factions, including Alfonsine monarchists, Carlists and Falangists. It also included political parties like Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (CEDA), Partido Republicano Radical (PRR), Derecha Liberal Republicana (DLR) and Lliga Catalana (LC). None of these had notable women's branches.[17] Most of the political activity from right leaning women came from Catholic women's groups, which public activity around unnerved conservative institutions because of problem of duality of these women seeking to protect the role of conservative women in the home while being highly visible in activist roles outside of it.[18] In 1928, ACM membership was at its peak with 119,000 women members.[18]

Women's rights

The Feminine Socialist Group of Madrid met in 1926 to discuss women's rights. Attendees included Victoria Kent and Clara Campoamor.[4] Agrupación Femenina Socialista de Madrid were active during this period. Trying to engage more broadly, they invited three Madrid based women lawyers, Victoria Kent, Clara Campoamor and Matilde Huici, to speak at Casa del Pueblo to better understand women's demands during the period in 1925 and 1926. By 19 March 1926, Campoamor had withdrawn her assistance to Socialists working on women's issues.[8]

Nelken saw both Socialists and the Catholics as offering little hope for women, as neither was capable of seeing the problems faced by women. This issue was one she saw as the central failing of feminism, a position that demonstrated a massive rift in Spanish feminism in the Primo de Rivera period.[8]

Employment and labor organizations

40% of all Spanish working women in 1930 worked in domestic roles, representing the largest single industry for which women were present.[4] Despite Primo de Rivera's view about the role of women, women were still able at times to have high ranking places in Spanish bureaucracy.[19]

Education

Things began to slowly change, with women's access to education. They had a literacy rate of 62% by 1930 and the gender ratio in schools being close to 50/50 on the primary school level.[10][20] This did not carry over to universities, where only 4.2% of students were women in 1928.[10]

Prior to the Second Republic, Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) recognized that women workers lacked a compensatory educational system and access to educational facilities that was equivalent to their male peers. Yet, despite this, they failed to offer any sort of comprehensive policy solution to this problem and were not willing to advocate strongly on the need to address women's education. The extent of their activism for women's education were demands for integral education for men and women.[21]

Art

Women were involved in the arts during this period. Maruja Mallo and Concha Mendez, painters, were both part of the Generation of 1927 and active in Madrid.[4] They lived at the Students Residence in Madrid, which during the 1920s and 1930s was home to Spain's avant-garde movement.[22] Originally from Galicia, Maruja Mallo would go with Concha Mendez and other famous male painters of the day, searching for supplies that defined Spanish live in that period.[22][4]

Daily life for women

In the days of the pre-Republic period and dictatorship, women on the streets of major cities like Barcelona and Madrid were often subjected to street harassment.[23]

Women entered the workforce in much more visible numbers in this period, working in universities, and the service sector. Women had also encroached on the previously masculine domain of cafes and ateneos. The 1920s saw a backlash against women in conservative circles, with many men seeing these women as gender confused.[24]

In the lead up to the founding of the Second Republic and the Civil War, many middle class and upper-class women who became feminists did so as a result boarding school educations resulting in parents unable to guide the evolution of their political thoughts, fathers encouraging daughters towards political thinking, or being indoctrinated in classes essentially aimed at reinforcing societal gender norms. Left leaning families were more likely to see their ideas manifested by their daughters as feminists through active influence. Right leaning families were more likely to see their daughters become feminists through rigid gender norms resulting in a familial break.[4]

References

- ^ a b de Ayguavives, Mònica (2014). Mujeres Libres: Reclaiming their predecessors, their feminisms and the voice of women in the Spanish Civil War history (Masters Thesis). Budapest, Hungary: Central European University, Department of Gender Studies.

- ^ Ben-Ami, Shlomo (1977). "The Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera: A Political Reassessment". Journal of Contemporary History. 12 (1): 65–84. doi:10.1177/002200947701200103. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 260237. S2CID 155074826.

- ^ "Los orígenes del sufragismo en España" (PDF). Espacio, Tiempo y Forma (in Spanish). 16. Madrid: UNED (published January 2015): 455–482. 2004. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mangini, Shirley; González, Shirley Mangini (1995). Memories of Resistance: Women's Voices from the Spanish Civil War. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300058161.

- ^ Congress. "Documentos Elecciones 12 de septiembre de 1927". Congreso de los Diputados. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d Martínez, Keruin P. (30 December 2016). "La mujer y el voto en España". El Diaro (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ a b c "Los orígenes del sufragismo en España" (PDF). Espacio, Tiempo y Forma (in Spanish). 16. Madrid: UNED (published January 2015): 455–482. 2004. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Díaz Fernández, Paloma (2005). "La dictadura de Primo de Rivera. Una oportunidad para la mujer" [The Primo de Rivera's dictatorship: An opportunity for women] (PDF). Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. 17: 175–190.

- ^ a b c "Los orígenes del sufragismo en España" (PDF). Espacio, Tiempo y Forma (in Spanish). 16. Madrid: UNED (published January 2015): 455–482. 2004. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Lines, Lisa Margaret (2012). Milicianas: Women in Combat in the Spanish Civil War. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739164921.

- ^ a b c Ripa, Yannick (2002). "Féminin/masculin : les enjeux du genre dans l'Espagne de la Seconde République au franquisme". Le Mouvement Social (in French). 1 (198). La Découverte: 111–127. doi:10.3917/lms.198.0111.

- ^ Orriols, Lluís; Lavezzolo, Sebastián (3 July 2017). "Las primeras 40 parlamentarias". El Diario (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ a b Montagut, Eduardo. "Primo de Rivera, la Asamblea Nacional Consultiva y los socialistas". EL OBRERO, Defensor de los Trabajadores (in European Spanish). Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ a b Congress. "Documentos Elecciones 12 de septiembre de 1927". Congreso de los Diputados. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Giménez Martínez, Miguel Ángel (Summer 2018). "La representación política en España durante la dictadura de Primo de Rivera". Estudos Históricos. 31 (64) (64 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: 131–150. doi:10.1590/S2178-14942018000200002.

- ^ Congress. "Documentos Elecciones 12 de septiembre de 1927". Congreso de los Diputados. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 9781780224534.

- ^ a b Bunk, Brian D. (2007-03-28). Ghosts of Passion: Martyrdom, Gender, and the Origins of the Spanish Civil War. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822339434.

- ^ Memory and Cultural History of the Spanish Civil War: Realms of Oblivion. BRILL. 2013-10-04. ISBN 9789004259966.

- ^ Cook, Bernard A. (2006). Women and War: A Historical Encyclopedia from Antiquity to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851097708.

- ^ Nash, Mary (1995). Defying male civilization: women in the Spanish Civil War. Arden Press. ISBN 9780912869155.

- ^ a b Bieder, Maryellen; Johnson, Roberta (2016-12-01). Spanish Women Writers and Spain's Civil War. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134777167.

- ^ Fraser, Ronald (2012-06-30). Blood Of Spain: An Oral History of the Spanish Civil War. Random House. ISBN 9781448138180.

- ^ Radcliff, Pamela Beth (2017-05-08). Modern Spain: 1808 to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405186803.