Vexillology of the Eureka Rebellion

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Eureka Rebellion |

|---|

|

|

|

The vexillological aspects of the Eureka Rebellion include the Eureka Flag and others used in protest on the goldfields and those of the British army units at the Battle of the Eureka Stockade. The disputed first report of the attack on the Eureka Stockade also refers to a Union Jack, known as the Eureka Jack, being flown during the battle that was captured, along with the Eureka Flag, by the foot police.[1]

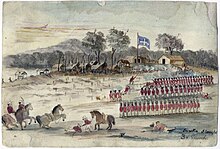

Bendigo diggers flag

The Bendigo "diggers flag" was unfurled at a rally at View Point, Sandhurst, on 12 August. It was reported that the miners paraded under the flags of several nations, including the Irish tricolour, the saltire of Scotland, the Union Jack, revolutionary French and German flags, and the Stars and Stripes. The delegates returned from Melbourne with news of the failure of the Bendigo petition. During the winter of 1853, the Red Ribbon Movement was active across the goldfields. Supporters wore red ribbons in their hats and were determined to hand over only 10 shillings for the licence fee and allow the sheer numbers in custody to cause an administrative meltdown.[2][3] Clark states that:

... ten to twelve thousand diggers turned up wearing a red ribbon in their hats. The old cabbage-tree hat of the Sydney radicals and republicans are now decorated with the red of revolution. Foreigners of all descriptions boasted that if the demands of the diggers were not instantly granted, they would lead them on to blood and victory. In alarm, George Thompson called three cheers for the good old Union Jack and asked them to remember that they were pledged to what he called 'necessary reform, not revolution'. William Dexter, waiving the diggers' flag, roared to them about the evils of 'English Tyranny' and the virtues of 'Republicanism'.[4]

There was a second multinational-style assembly at View Point on 27 August.

Regimental flags

The colour sergeant for the 40th regiment was John Macoboy.[5]

Eureka Flag

The Eureka Flag was flown by the rebel garrison over the Eureka Stockade when it was besieged by colonial forces on 3 December 1854 at Ballarat, Victoria, Australia. It was the culmination of the 1851–1854 Eureka Rebellion during the Victorian gold rush. The fighting resulted in at least 27 deaths and many injuries, the majority of casualties being rebels. The miners had various grievances, chiefly the cost of mining permits and the officious way the system was enforced. There was an armed uprising in Ballarat where tensions were brought to a head following the death of miner James Scobie. On 29 November 1854, the Eureka Flag was raised during a paramilitary display on Bakery Hill that resulted in the formation of rebel companies and the construction of a crude battlement on the Eureka lead.

The earliest mention of a flag was the report of a meeting held on 23 October 1854 to discuss indemnifying Andrew McIntyre and Thomas Fletcher, who had both been arrested and committed for trial over the burning of the Eureka Hotel. The correspondent for the Melbourne Herald stated: "Mr. Kennedy suggested that a tall flag pole should be erected on some conspicuous site, the hoisting of the diggers' flag on which should be the signal for calling together a meeting on any subject which might require immediate consideration."[6]

In 1885, John Wilson, whom the Victorian Works Department employed at Ballarat as a foreman, claimed that he had originally conceptualised the Eureka Flag after becoming sympathetic to the rebel cause. He then recalls that it was constructed from bunting by a tarpaulin maker.[7][8] There is another popular tradition where the flag design is credited to a member of the Ballarat Reform League, "Captain" Henry Ross of Toronto, in Ontario, Canada. A. W. Crowe recounted in 1893 that "it was Ross who gave the order for the insurgents' flag at Darton and Walker's".[9] Crowe's story is confirmed in that there were advertisements in the Ballarat Times dating from October–November 1854 for Darton and Walker, manufacturers of tents, tarpaulin and flags, situated at the Gravel Pits.[10]

It has long been said that women were involved in constructing the Eureka Flag. In a letter to the editor published in the Melbourne Age, 15 January 1855 edition, Fredrick Vern states that he "fought for freedom's cause, under a banner made and wrought by English ladies".[11] According to some of their descendants, Anastasia Withers, Anne Duke and Anastasia Hayes were all involved in sewing the flag.[12][note 1] The stars are made of delicate material, consistent with the story they were made out of their petticoats.[16] The blue woollen fabric "certainly bears a marked resemblance to the standard dressmaker's length of material for making up one of the voluminous dresses of the 1850s"[10] and also the blue shirts worn by the miners.[14]

In his seminal Flag of Stars, Frank Cayley published two sketches he discovered on a visit to the soon-to-be headquarters of the Ballarat Historical Society in 1963, which may be the original plans for the Eureka Flag. One is a two-dimensional drawing of a flag bearing the words "blue" and "white" to denote the colour scheme. Cayley has concluded: "It looks like a rough design of the so-called King Flag."[17] The other sketch was "pasted on the same piece of card shows the flag being carried by a bearded man" that Cayley believes may have been intended as a representation of Henry Ross.[18][note 2] Federation University history professor Anne Beggs-Sunter refers to an article reportedly published in the Ballarat Times "shortly after the Stockade referring to two women making the flag from an original drawing by a digger named Ross. Unfortunately no complete set of the Ballarat Times exists, and it is impossible to locate this intriguing reference."[14][21][22]

The theory that the Eureka Flag is based on the Australian Federation Flag has precedents in that "borrowing the general flag design of the country one is revolting against can be found in many instances of colonial liberation, including Haiti, Venezuela, Iceland, and Guinea".[23][24] Some resemblance to the modern Flag of Quebec has been noted,[25] that was based on a design used by the French-speaking majority of the colony of the Province of Canada at the time Ross emigrated. Ballarat local historian Father Tom Linane thought women from the St Aliphius chapel on the goldfields might have made the flag. This theory is supported by St. Aliphius raising a blue and white ecclesiastical flag featuring a couped cross to signal that mass was about to commence.[26][27] Professor Geoffrey Blainey believed that the white cross on which the stars are arrayed is "really an Irish cross rather than being [a] configuration of the Southern Cross".[28]

Cayley has stated that the field "may have been inspired by the sky, but was more probably intended to match the blue shirts worn by the diggers".[29] Norm D'Angri theorises that the Eureka Flag was hastily manufactured, and the number of points on the stars is a mere convenience as eight was "the easiest to construct without using normal drawing instruments".[30]

Exhibit in high treason trials

At the Eureka state treason trials that began on 22 February 1855, the 13 defendants had it put to them that they did "traitorously assemble together against our Lady the Queen" and attempt "by the force of arms to destroy the Government constituted there and by law established, and to depose our Lady the Queen from the kingly name and her Imperial Crown".[31] Furthermore, concerning the "overt acts" that constituted the actus reus of the offence, the indictment read: "That you raised upon a pole, and collected round a certain standard, and did solemnly swear to defend each other, with the intention of levying war against our said Lady the Queen".[31]

Called as a witness, George Webster, the chief assistant civil commissary and magistrate, testified that upon entering the stockade the besieging forces "immediately made towards the flag, and the police pulled down the flag".[32] John King testified, "I took their flag, the southern cross, down – the same flag as now produced."[33]

In his closing submission, the defence counsel Henry Chapman argued there were no inferences to be drawn from the hoisting of the Eureka Flag, saying:

and if the fact of hoisting that flag be at all relied upon as evidence of an intention to depose Her Majesty ... no inference whatever can be drawn from the mere hoisting of a flag as to the intention of the parties, because of the witnesses has said that two hundred flags were hoisted at the diggings; and if two hundred persons on the same spot choose to hoist their particular flag, what each means we are utterly unable to tell, and no general meaning as to hostility to the Government can be drawn from the simple fact that the diggers on that occasion hoisted a flag ... I only throw it out to you because it is utterly impossible, in the multiplicity of flags that have been hoisted on the diggings, to draw an exact inference as to the hoisting of any one particular flag at one spot.[34]

Eureka Jack Mystery

Since 2012, various theories have emerged, based on the Argus account of the battle dated 4 December 1854 and an affidavit sworn by Private Hugh King three days later as to a flag being seized from a prisoner detained at the stockade, concerning whether a Union Jack, known as the Eureka Jack was also flown by the rebel garrison. Readers of the Argus were told that:

The flag of the diggers, "The Southern Cross," as well as the "Union Jack," which they had to hoist underneath, were captured by the foot police.[1]

In his Eureka: The Unfinished Revolution, Peter FitzSimons has stated:

In my opinion, this report of the Union Jack being on the same flagpole as the flag of the Southern Cross is not credible. There is no independent corroborating report in any other newspaper, letter, diary or book, and one would have expected Raffaello Carboni, for one, to have mentioned it had that been the case. The paintings of the flag ceremony and battle by Charles Doudiet, who was in Ballarat at the time, depicts no Union Jack. During the trial for high treason, the flying of the Southern Cross was an enormous issue, yet no mention was ever made of the Union Jack flying beneath.[35]

However, Hugh King, who was a private in the 40th (the 2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot, swore in a signed contemporaneous affidavit that he recalled:

... three or four hundred yards a heavy fire from the stockade was opened on the troops and me. When the fire was opened on us we received orders to fire. I saw some of the 40th wounded lying on the ground but I cannot say that it was before the fire on both sides. I think some of the men in the stockade should – they had a flag flying in the stockade; it was a white cross of five stars on a blue ground. – flag was afterwards taken from one of the prisoners like a union jack – we fired and advanced on the stockade, when we jumped over, we were ordered to take all we could prisoners ...[36]

During the committal hearings for the Eureka rebels, there would be another Argus report dated 9 December 1854 concerning the seizure of a second flag at the stockade in the following terms:

The great topic of interest to-day has been the proceedings in reference to the state prisoners now confined in the Camp. As the evidence of the witnesses in these cases is more reliable information than that afforded by most reports, I shall endeavor to give you an abstract of it.[37]

Hugh King was called upon to give further testimony live under oath in the matter of Timothy Hayes. In doing so, he went into more detail than in his written affidavit, as the report states that the Union Jack-like flag was found:

... rollen up in the breast of a[n] [unidentified] prisoner. He [King] advanced with the rest, firing as they advanced ... several shots were fired on them after they entered [the stockade]. He observed the prisoner [Hayes] brought down from a tent in custody.[37]

Military historian and author of Eureka Stockade: A Ferocious and Bloody Battle Gregory Blake, concedes that the rebels may have flown two battle flags as they claimed to be defending their British rights. Blake leaves open the possibility that the flag being carried by the prisoner had been souvenired from the flag pole as the routed garrison was fleeing the stockade. Once taken by Constable John King, the Eureka Flag was placed beneath his tunic in the same fashion as the suspected Union Jack was found on the prisoner.[38]

In 1896, Sergeant John McNeil, who was at the battle, recalled shredding a flag at the Spencer Street Barracks in Melbourne at the time. He claimed it was the Eureka Flag that he had torn down.[39] However, Blake believes it may have been the mystery Eureka Jack.[40]

Another theory is that the Eureka Jack was an 11th-hour response to divided loyalties in the rebel camp.[41][note 3]

The oath swearing ceremony in Eureka Stockade (1949) features the star-spangled Eureka Flag with the Union Jack beneath.[44] In The Revolt at Eureka, part of a 1958 illustrated history series for students, the artist Ray Wenban remained faithful to the first reports of the battle with his rendition featuring two flags flying above the Eureka Stockade.[45]

In 2013, the Australian Flag Society announced a worldwide quest and a $10,000 reward for more information and materials relating to the Eureka Jack mystery.[41] The AFS also released a commemorative artwork, "Fall Back with the Eureka Jack" illustrating Gregory Blake's theory for the 160th anniversary of the battle in 2014.[46]

Notes

- ^ Anastasia Withers was first mentioned in connection with the Eureka Flag in a 1986 article entitled "Women and the Eureka Flag" published in Overland.[13] The author Len Fox had received correspondence from Val D'Argri who had been informed by an aunt, May Flavell, that her great grandmother was one of three women responsible for sewing the Eureka Flag. In 1992, Fox also named Anne Duke for the first time on the basis of oral tradition preserved by the organisation Eureka's Children, which was formed in 1988 by descendants of those who took part in the Eureka Rebellion. Anastasia Hayes was only put forward in 2000 by her descendant Anne Hall, a Children of Eureka committee member.[14] In 1889, William Withers interviewed Anastasia Hayes for his 1870 book on the history of Ballarat. Hayes recalled being present when Peter Lalor's arm was amputated in the St Alipius presbytery. However, she apparently mentioned nothing about the Eureka Flag.[15]

- ^ Ballarat militaria consultant Paul O'Brien has carried out an expert analysis of the Cayley sketches concluding that: "This sketch, once in the collection of the Ballarat Historical Society, location now unknown, was originally displayed with another sketch representing the 'Eureka' or 'King' flag and was labelled 'Found in a Tent After the Affair at Eureka'. The sketches were first reproduced in Frank Cayley's book Flag of Stars.[19] The assumption made in the accompanying text was that the sketch was a draft design for the making of the flag. While this assumption is quite plausible, it would seem more likely that the sketch was made after the capture of the flag. Note the tattered leading edge and indistinct star. The number of points to the stars represented also does not tally with those on the surviving 'King' flag. This sketch was, perhaps, drawn after the flag was 'brought in triumph' to the government camp and while it was being savaged by eager souvenir hunters. The two sketches have been drawn by different hands, and many details of design differ considerably (notably the hoist edge and number of star points). The size of the flag in the sketch with figure does not tally with the enormous size of the 'King' flag, and is probably a later, not contemporary, representation."[20]

- ^ Peter Lalor made a blunder by choosing "Vinegar Hill" – the site of a battle during the Irish Rebellion of 1798 – as the rebel password. This led to waning support for the Eureka Rebellion as news that the issue of Irish independence had become involved began to circulate.[42][43]

References

- ^ a b "By Express. Fatal Collision at Ballaarat". The Argus. Melbourne. 4 December 1854. p. 5. Retrieved 17 November 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ Hocking 2004, p. 71.

- ^ Clark 1987, p. 64.

- ^ Clark 1987, p. 63-64.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 79.

- ^ "Ballaarat". Launceston Examiner. Launceston. 7 November 1854. p. 2. Retrieved 17 November 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ Wilson, John (19 December 1885). "The Starry Banner of Australia". The Capricornian. Rockhampton. p. 29. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Wilson 1963, pp. 6–7.

- ^ "Untitled". Ballarat Star. Ballarat. 4 December 1854. p. 2. Retrieved 17 November 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ a b Beggs-Sunter 2004, p. 48.

- ^ Carboni 1855, p. 97.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 190.

- ^ Fox, Len (December 1986). "Women and the Eureka Flag". Overland. Vol. 105. Melbourne. pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b c Beggs-Sunter 2014.

- ^ Withers 1999, p. 239.

- ^ This oral tradition is referred to in the Sydney Sun, 5 May 1941, p. 5. See also Withers in his report in the Ballarat Star, 1 May 1896, p. 1.

- ^ Cayley 1966, p. 82.

- ^ Cayley 1966, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Cayley 1966.

- ^ O'Brien 1992, p. 81.

- ^ The Sydney Sun, 5 May 1941 edition, page 4, mentions issues of the Ballarat Times in the Mitchell Library.

- ^ Fox 1992, p. 49.

- ^ Smith 1975b, p. 60.

- ^ Beggs-Sunter 2004, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Wickham, Gervasoni & D'Angri 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Bate 1978, p. 63.

- ^ Wickham, Gervasoni & D'Angri 2000, p. 11.

- ^ "Historians discuss Eureka legend". Lateline. 7 May 2001. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Cayley 1966, p. 76.

- ^ Wickham, Gervasoni & D'Angri 2000, p. 62.

- ^ a b The Queen v Hayes and others, 1 (Supreme Court of Victoria 1855).

- ^ The Queen v Joseph and others, 35 (Supreme Court of Victoria 1855).

- ^ "Continuation of the State Trials". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. 5 March 1855. p. 3. Retrieved 17 November 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ The Queen v Joseph and others, 43 (Supreme Court of Victoria 1855).

- ^ FitzSimons 2012, pp. 654–655, note 56.

- ^ King, Hugh (7 December 1854). "Deposition of Witness: Hugh King". Public Record Office Victoria. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ a b "BALLAARAT". The Argus. Melbourne. 9 December 1854. p. 5. Retrieved 17 November 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ FitzSimons 2012, p. 477.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 357.

- ^ Blake 2012, pp. 243–244, note 78.

- ^ a b Cowie, Tom (22 October 2013). "$10,000 reward to track down 'other' Eureka flag". The Courier. Ballarat. p. 3. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Nicholls, H.R (May 1890). Reminiscences of the Eureka Stockade. The Centennial Magazine: An Australian Monthly. II: August 1889 to July 1890 (available in an annual compilation). p. 749.

- ^ Craig 1903, p. 270.

- ^ Harry Watt (director) (1949). Eureka Stockade (Motion picture). United Kingdom and Australia: Ealing Studios.

- ^ Wenban 1958, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Henderson, Fiona (23 December 2014). "Reward offered for evidence of battle's Union Jack flag". The Courier. Ballarat. p. 5.

Bibliography

Historiography

- Blake, Gregory (2012). Eureka Stockade: A ferocious and bloody battle. Newport: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1-92-213204-8.

- FitzSimons, Peter (2012). Eureka: The Unfinished Revolution. Sydney: Random House Australia. ISBN 978-1-74-275525-0.

- Wenban, Ray (1958). The Revolt at Eureka. Pictorial Social Studies. Vol. 16. Sydney: Australian Visual Education.

- Withers, William (1999). History of Ballarat and Some Ballarat Reminiscences. Ballarat: Ballarat Heritage Service. ISBN 978-1-87-647878-0.

Vexillology

- Smith, Whitney (1975). Flags Through the Ages and Across the World. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-059093-9.

Primary sources

Memoirs

- Craig, William (1903). My Adventures on the Australian Goldfields. London: Cassell and Company.

- Nicholls, H.R (May 1890). Reminiscences of the Eureka Stockade. The Centennial Magazine: An Australian Monthly. II: August 1889 to July 1890 (available in an annual compilation).

Newspaper reports

- "By Express. Fatal Collision at Ballaarat". The Argus. Melbourne. 4 December 1854. p. 5. Retrieved 19 July 2023 – via Trove.

- "BALLAARAT". The Argus. Melbourne. 9 December 1854. p. 5. Retrieved 17 November 2020 – via Trove.

- Cowie, Tom (22 October 2013). "$10,000 reward to track down 'other' Eureka flag". The Courier. Ballarat. p. 3. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Henderson, Fiona (23 December 2014). "Reward offered for evidence of battle's Union Jack flag". The Courier. Ballarat. p. 5.

Reference books

- Corfield, Justin; Wickham, Dorothy; Gervasoni, Clare (2004). The Eureka Encyclopedia. Ballarat: Ballarat Heritage Services. ISBN 978-1-87-647861-2.