User:QuackGuru/Sand 15

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/30/health/vaping-juul-international.html

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=pod+mod&filter=years.2021-2021&size=200

Pod mod electronic cigarettes heat up a liquid containing nicotine, flavors, and other ingredients that creates an aerosol.[3] Pod mods are lightweight, portable,[4] small, and reusable.[5] Pod mods do not require pushing a button.[6] There are numerous pod mods in the marketplace[7] and there are many kinds of pod mods.[8] Many devices rely on replaceable liquid pods that may contain propylene glycol, glycerin, benzoic acid, nicotine, and artificial flavors.[9] Some pod mods can be refillable, with flavors such as cotton candy, donut cream, and gummy bear.[7] Pod mods can look like USB flash drives, cell phones, credit card holders, and highlighters.[10] Because pod mods are small and generate less aerosol, it makes it easy to hide them.[11]

Pod mods have increased in use among adolescents and young adults.[7] Youth who try pod mods seem to have a greater potential to become frequent users than those who try other electronic or traditional cigarettes.[7] Pod mods are the most commonly used nicotine product among youth.[12] They have the potential to be used unobtrusively in areas where smoking is not allowed.[13] Pod mods are more socially appealing than traditional cigarettes among adolescents and young adults.[13] College students in the US stated their distaste for the tobacco flavor and considered it an impendent to both starting and continuing to use e-cigarettes.[14] Despite the clear presence of nicotine in e-cigarettes, adolescents often do not recognize this fact, potentially fueling misperceptions about the health risks and addictive potential of e-cigarettes.[15]

Nicotine is highly addictive and can harm brain development, which continues until about age 25.[16] Pod mods contain high concentrations of nicotine that can lead to nicotine dependence.[17] Pod mods effectively delivers nicotine and as a result magnifies the chance of nicotine dependence among minors.[18] Minors using pod mods are more likely than traditional e-cigarette users to exhibit higher nicotine dependence symptoms.[18] The potential for a continued life-long addiction to nicotine among minors is a significant public health concern.[18] Given the high nicotine concentrations in Juul, the nicotine-related health consequences of its use by young people could be more severe than those from their use of other e-cigarette products.[19] Nicotine poses an array of health risks[20] such as the stimulation of cancer development and growth.[21] Several studies demonstrate it is carcinogenic.[20] Because it can form nitrosamine compounds (particularly N-Nitrosonornicotine (NNN) and nicotine-derived nitrosamine ketone (NNK)) through a conversion process, nicotine itself exhibits a strong potential for causing cancer.[22]

The long-term effects of pod mod use, including their effects on the growing brain, is largely unknown.[13] The liquid pods also contain propylene glycol, which has been shown to induce airway epithelial injury and deep airway inflammation.[9] Research on nicotine salts is limited.[4] Possible health risks of persistent inhalation of high levels of nicotine salts are not known.[4] Principal Deputy Director Dr. Anne Schuchat of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated in September 2019 that the nicotine salts "cross the blood brain barrier and lead to potentially more effect on the developing brain in adolescents."[23] Pod mods deliver higher levels of nicotine than regular e-cigarettes[24] in protonated salt rather than the free-base nicotine form found in earlier generations.[15] There has been a proliferation of pod-based products with high nicotine concentration, triggered by Juul's financial success.[25] Pod mods are heavily marketed, with a particular focus in the way youth can use them discreetly.[26] The prevalence of newer types of e-cigarettes, like Juul, with greater levels of nicotine is a public health disaster.[27]

Usage

Prevalence

Pod mods have increased in use among adolescents and young adults[7] and are more popular among youth and young adults in contrast to traditional e-cigarettes.[28] Pod mod devices have become popular among teenagers as a socially acceptable alternative to conventional cigarettes due to their stylish design (e.g. USB or teardrop shape), wide selection of flavors, and user-friendly functions.[29] Among youth and adults, pod mods have been a quickly rising public health issue in 2021.[30] Youth who try pod mods seem to have a greater potential to become frequent users than those who try other electronic or traditional cigarettes.[7] The explosion in e-cigarette use in the US was associated with Juul that was available in a myriad of flavors.[31] Pod mods were the most commonly used nicotine product among youth in 2018.[12] Minors in the US do not have any major problem in obtaining vaping products online or from friends and family members.[31]

Flavors. which are especially enticing to youth. have been prohibited in the US from use in closed-cartridge devices such as Juul.[31] The revised US FDA rules would emphasize the ban of flavored cartridges or pod-based vaping products to curb their appeal to youth, but this rule did not apply to tobacco flavored or menthol flavored cartridges, tobacco flavored or menthol flavored pod-based vaping products, flavored non-reusable vaping products, or refillable flavored e-liquids.[32] For this reason, numerous flavored e-cigarette products were still in the marketplace, which has resulted in a surge in the utilization of non-reusable e-cigarettes among middle and high school students in the US from 2019 to 2020.[32]

In December 2017, Juul was the top-selling e-cigarette brand in the US.[16] By April 2022, Vuse was at 35.1% and Juul was at 33.1% of the market in the US.[33] Vuse lead increased to 39.7%, while Juul's market share in the US slumped to 28.1% by September 2022.[34]

A 2018 study stated that 80% of people aged 15 to 24 who experimented with Juul persisted using the device and comments on social media stating "addicted to my Juul" were frequent.[5] Pod mods comparable to Juul have the potential to be used unobtrusively in areas where smoking is unlawful.[13] The escalation in use of vaping products including pod mods seems to be associated with the millions of youth who had seen the advertisements of such products.[13] "Exemplifying concern with youth uptake and use of e-cigarettes in general and pod-based e-cigarettes in particular, the US Food and Drug Administration released a statement in April 2018 on new enforcement actions and a Youth Tobacco Prevention Plan to stop youth use of, and access to, JUUL (brand name for a pod-based e-cigarette) and other e-cigarettes," a 2018 report stated.[35]

Pod mods used by youth on school property and during class is seemingly pervasive.[8] News outlets and social media sites report widespread use of Juul by students in schools, including in classrooms and bathrooms.[16] Schools are having difficulty to stop students from using pod mods in restrooms, hallways, and classrooms.[36] Some schools do not allow any USB flash drives on their property because many pod mods look like USB flash drives.[5] School districts have started educating parents and teachers about pod mods.[5] The educational school programs teach how to find out if their son or daughter or a student is using a pod mod.[5] E-cigarette devices are compact and inconspicuous, resembling a USB flash drive, and are easy to conceal from authority figures, facilitating widespread use even in the classroom.[19] In 2017, students had commented on Twitter about using the Juul device in class.[37] Their likeness to an USB memory stick allows them to be discretely used in no smoking areas and easily concealed from parents, contributing to a new widespread phenomenon, known as "stealth vaping".[29] E-cigarette use has become so pervasive among youth that it is impossible to go to the bathroom in many middle and high schools because so many people are "Juuling" (i.e. vaping).[19] In response, several Massachusetts high schools have started to lock the bathrooms in order to prevent e-cigarette use during the school day.[19] Parents may not realize that their child is vaping.[38] For example, just 44.2% of parents of middle school and high school students were able to recognize a Juul device.[38]

Subsequent youth smoking initiation

Teens who vape are more likely to start using tobacco products.[26] Youth who vape are more likely than non-users to start smoking cigarettes, and the higher nicotine concentrations in Juul might heighten the likelihood of this transition.[19] Juul vaping among youth could result in gateway effects, such as starting smoking or cannabis use, is an area of concern.[39] Many studies have confirmed a gateway effect from early nicotine use, and many pod-based nicotine products, like Juul and disposable e-cigarettes, have high levels of nicotine that result in rapid addiction by users.[40] E-cigarette use not only results in the dual use of nicotine products but also leads to nicotine and cannabis product use, a practice of growing concern to researchers as cannabis becomes legal in more countries.[40]

Motivation

Pod mods are more socially appealing than traditional cigarettes among adolescents and young adults.[13] Pod mods made e-cigarette use more appealing because of their convenience, design, ease of concealment, and flavors, though college students in the US stated their distaste for the tobacco flavor and considered it an impendent to both starting and continuing to use e-cigarettes.[14] For example, a male sophomore student in the US stated that "if they eliminated everything but the tobacco pods, I would probably stop [vaping]."[14] Youth may be using pod mods because they think these devices are safer to use.[13] Juul and other vaping companies have stated they want to provide users a more similar cigarette-like experience in order to entice to smokers.[41] The enticement of flavored vape pods to small children could cause them to drink the liquid.[13]

Public perception

Despite the clear presence of nicotine in e-cigarettes, adolescents often do not recognize this fact, potentially fueling misperceptions about the health risks and addictive potential of e-cigarettes.[15] A 2018 study found 63% of respondents aged 15 to 24 were not aware that every Juul product contains nicotine.[5]

Construction

Pod mods heat up a liquid containing nicotine, flavors, and other ingredients that creates an aerosol.[3] Pod mods are lightweight, portable,[4] small, and reusable.[5] Pod mods do not require pushing a button.[6] A pod mod does not require much of a learning curve.[6] With the majority of pod mods, users can just open their new package, put a pod into the device, and begin vaping.[5] They are charged using a USB port.[6] There are numerous pod mods in the marketplace[7] and there are many kinds of pod mods.[8] The three categories for the different kinds of pod mods are an open system, a closed system, or those that use both.[8]

Pod mods come in many shapes, sizes, and colors.[42] They also come in come in varying flavors.[43] Common pod mod brands include Juul and Suorin.[42] Many devices rely on replaceable liquid pods that may contain propylene glycol, glycerin, benzoic acid, nicotine, and artificial flavors.[9] Some pod mods can be refillable, with flavors such as cotton candy, donut cream, and gummy bear.[7] Pod mods that contain tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive chemical of cannabis, are being sold.[7] There are compatible prefilled pod cartridges that contain nicotine, THC, or cannabidiol (CBD) with or without flavoring.[42] Users may hack closed systems (such as pod/cartridge devices) to refill these cartridges with other substances.[42] Pod mods can look like USB flash drives, cell phones, credit card holders, and highlighters.[10] Because pod mods are small and generate less aerosol, it makes it easy to hide them.[11] There are pod mods that can be concealed in the palm of a person's hand.[11] Later-generation pod mods are small like a Sharpie pen.[6] YouTube videos teach viewers how to conceal Juul devices, with one video concealing a Juul device inside a Sharpie pen.[26] Pod mods cost about half as much as larger e-cigarettes.[6]

Health effects

Safety

The long-term effects of pod mod use, including the effects on the growing brain, is largely unknown.[13] In sampling multiple e-cigarette delivery systems, a 2019 study found Juul pods were the only product to demonstrate in vitro cytotoxicity from both nicotine and flavor chemical content, in particular ethyl maltol.[9] Vape liquid pods may contain numerous other compounds and are known to provide unreliable nicotine delivery that is often inconsistent with the labeling.[9] A 2019 study testing popular pod mods from the US showed that 81% of them contained B-D-glucan and 23% contained endotoxin.[44]

These liquid pods also contain propylene glycol, which has been shown to induce airway epithelial injury and deep airway inflammation.[9] Many vape pods contain the flavoring chemicals diacetyl and 2,3-pentanedione.[9] These two specific compounds have been shown to directly alter the transcriptional profiles of primary human bronchial epithelial cells grown at air–liquid interface, phenotypically leading to impaired ciliogenesis.[9] The enticing pod flavoring to young children could result in them ingesting the liquid.[13] Youth regularly use more than one pod at a time, and as a consequence they may be unsuspectingly become exposed to toxic doses of nicotine that can have short-term and long-term health risks.[45]

Nicotine carcinogenicity

Nicotine poses an array of health risks[20] such as the stimulation of cancer development and growth.[21] The International Agency for Research on Cancer does not consider nicotine to be a carcinogen, though several studies demonstrate it is carcinogenic.[20] Because it can form nitrosamine compounds (particularly N-Nitrosonornicotine (NNN) and nicotine-derived nitrosamine ketone (NNK)) through a conversion process, nicotine itself exhibits a strong potential for causing cancer.[22] About 10% of breathed in nicotine is estimated to convert to these nitrosamine compounds.[22] Nitrosamine carcinogenicity is thought to be a result of enhanced DNA methylation and may lead to an agonist response on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which acts to encourage tumors to grow, stay alive, and penetrate into neighboring tissues.[22]

Nicotine salt

E-cigarettes containing nicotine salts aim to increase smoker's satisfaction by improving blood nicotine delivery and other sensory properties.[46] Research on nicotine salts is limited.[4] Possible health risks of persistent inhalation of high levels of nicotine salts are not known.[4] The long-term consequences of inhaling benzoic acid at the levels observed in nicotine salt e-liquids is unknown.[47] "Juul products use nicotine salts, which can lead to much more available nicotine," Principal Deputy Director Dr. Anne Schuchat of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated in September 2019.[23] She also stated that the nicotine salts "cross the blood brain barrier and lead to potentially more effect on the developing brain in adolescents."[23] Consequences of breathing in the nicotine salt aerosols on pregnant women and fetuses is not known.[48]

Nicotine salts used in later-generation devices may also have altered pharmacodynamics and acute effects relative to e-liquids containing free-base nicotine (conventionally used in e-liquids).[49] For instance, a 2021 study found that nicotine salt-based e-liquid had a more acidic pH (protonated) relative to more basic conventional (unprotonated) e-liquid; they postulated that this reduces systemic bioavailability because protonated nicotine has poorer membrane permeability.[49] Conversely, the authors of the 2021 study suggested that protonated nicotine is more likely to result in acute lung damage, as this is the form that binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (which activate inflammatory immune responses) lining the lung epithelium.[49] These receptors are also expressed on macrophages; accordingly, alveolar macrophage production of inflammatory cytokines is enhanced in the presence of nicotine-containing e-cigarette aerosol condensate compared to nicotine-free e-cigarette aerosol condensate.[49]

Nicotine delivery

The latest generation of e-cigarettes, "pod products," such as Juul, have the highest nicotine content (59 mg/mL), in protonated salt, rather than the free-base nicotine form found in earlier generations, which makes it easier for less experienced users to inhale.[15] Nicotine salt e-liquids have become so succusful that they provoked a "nicotine arms race."[50] Pod mods deliver higher levels of nicotine than regular e-cigarettes[24] and can expose users to nicotine levels that are similar to regular cigarettes.[14] They also increase blood levels of nicotine faster than cig-a-likes and advanced vaping devices.[51]

Prior to Juul hitting the market, 3% was the greatest amount of nicotine available from many companies.[52] One nicotine pod, in terms of nicotine, is roughly equivalent to one pack of regular cigarettes.[53] According to the manufacturer, a single Juul pod contains as much nicotine as a pack of 20 regular cigarettes.[16] A Juul pod containing 0.7 ml or 59 mgmg/mL (5%) of nicotine is equivalent to about 20 traditional cigarettes.[5] Each Juul pod could provide as much as 200 puffs.[54] The labels on products state pods contain 59 mg/mL of nicotine, but the levels can be considerably greater such as 75 mg/mL of nicotine.[7] Some pod mods contained greater levels of nicotine than Juul which were as high as 6.5%.[25] The majority of e-liquids contained 1% to 3% nicotine before Juul hit the market.[55] Given the high nicotine concentrations in Juul, the nicotine-related health consequences of its use by young people could be more severe than those from their use of other e-cigarette products.[19] The prevalence of newer types of e-cigarettes, including Juul, with greater levels of nicotine is a public health catastrophe.[27]

Tests show that the pod mods Juul, Bo, Phix, and Sourin contain nicotine salts in a solution with propylene glycol and glycerin.[4] Fontem Ventures, a unit of Imperial Brands, created myBlu pods that contain nicotine salts in a mixture with free-base nicotine and lactic acid.[41] The Juul pod mod e-liquid has a protonated nicotine content that is seven times greater than in a traditional blu e-cigarette e-liquid.[56] Nicotine salt is present in e-liquid as a product of combination of nicotine and various acids, such as glycolic, pyruvic, lactic, levulinic, fumaric, succinic, benzoic, salicylic, malic, tartaric and citric acids.[57] A nicotine base and a weak acid such as benzoic acid or levulinic acid is used to form a nicotine salt.[3] Benzoic acid is the most used acid to create a nicotine salt.[25] A free-base nicotine solution with an acid reduces the pH, which makes it possible to provide higher levels of nicotine without irritating the throat.[26] Nicotine salts are thought to amplify the level and rate of nicotine delivery to the user.[4] The speed of nicotine salts uptake into the body is close to the speed of nicotine uptake from traditional cigarettes.[58] Juul delivers nicotine 2.7 times faster than other e-cigarettes.[19] Grant O'Connell, overseer of scientific affairs at Imperial Brands, indicated that nicotine salts are able to go far deeper into the lungs than the free-base nicotine.[41] Since nicotine is absorbed quicker through the lungs, nicotine salts can more closely mimic the nicotine delivery experience from the use of regular cigarettes than nicotine in free-base nicotine e-liquids, according to O’Connell.[41] This means, according to O’Connell, that more of the nicotine in free-base nicotine e-liquids goes to the upper respiratory tract where it is absorbed into the blood more slowly.[41] Michael Siegel, a tobacco control advocate, said on October 16, 2019 at a subcommittee of Congress' House Committee on Energy and Commerce hearing that "The use of nicotine salts allows the nicotine to be absorbed into the bloodstream much more quickly, simulating the pattern you get with a real cigarette."[59]

Nicotine salts are less harsh and less bitter, and as a consequence e-liquids that contain nicotine salts are more tolerable even with high nicotine concentrations.[25] Regular e-cigarette e-liquids contain free-base nicotine in which higher nicotine levels can be unpleasant to the user.[5] Traditional cigarettes provide high levels of nicotine, but with the bad taste of smoking.[5] Pod mods, however, can provide high levels of nicotine without the negative smoking experience.[5] The amount of nicotine uptake from pod mod use among youth is greater than among those who use traditional cigarettes.[13] In a 2018 study of adolescent pod users, their urinary cotinine (a breakdown product used to measure nicotine exposure) levels were higher than levels seen in adolescent cigarette smokers.[15]

Metals

Heavy metals have been detected in the vape aerosols produced from pod-type vapes, including chromium, nickel, copper, zinc, cadmium, tin, manganese, and lead.[60] The metallic components of e-cigarette devices, such as the filaments and coils, are comprised of such heavy metals and can degrade when exposed to oxidized acidic e-liquids.[60] While metal exposure is a risk factor for multiple pulmonary diseases including respiratory inflammation, asthma, COPD, and respiratory cancer, the health effects of metal exposure in e-cigarette users is still largely unknown.[60]

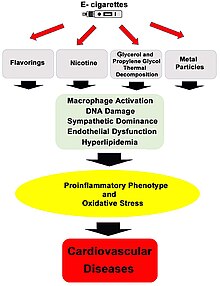

Cardiovascular effects

Several in vitro and in vivo studies describing the mechanisms of the impact of e-cigarettes on the cardiovascular system have been published.[61] These include mechanisms associated with nicotine or other components of the aerosol or thermal degradation products of e-cigarettes.[61] It remains uncertain that the cardiovascular effects of pod mod use will lead to a significant harm reduction in issues associated with cardiovascular disease.[62]

Nicotine has systemic hemodynamic effects that are mediated by the activation of the sympathetic nervous system.[61] Thus, acute nicotine treatment can stimulate cardiac output by producing systemic vasoconstriction and increasing heart rate.[61] A 2022 study found that "Pod-based Electronic Cigarette (PEC) use had comparable short-term and long-lasting impacts on vascular function, BP, and HR as conventional cigarette use among young and healthy adults. Findings indicated that PECs release volatile organic compound (VOC) chemicals that have toxic effects on the blood vasculature."[40]

Inhaling e-cigarettes (Juul with nicotine) acutely increased sympathetic neural outflow in young, healthy non-smokers.[61] In contrast, inhalation of a placebo e-cigarette without nicotine elicited no sympathetic dominance.[61] Therefore, the sympathetic dominance produced by e-cigarettes is mainly produced by nicotine.[61]

A 2021 study concluded that Juul and other pod mods increased the blood pressure by 6 mm Hg acutely in comparison to nicotine-free e-cigarettes.[61] Nevertheless, the authors of this study have mentioned that the 6 mmHg of increase could be underestimated because the participants were not experienced e-cigarette users, which means there could of been less nicotine absorption.[61]

Respiratory effects

The significant concentrations of flavorings in Juul e-liquids can harm or destroy lung cells.[30]

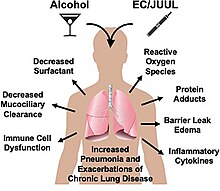

Alcohol effects

Given the relative newness of e-cigarettes, such as Juul, as of 2020, there is a limited body of literature detailing the role e-cigarettes play in alcohol consumption, how inaccurate perceptions of e-cigarettes contribute to risk-taking behaviors related to alcohol consumption, and the pathogenic damages that occur during dual use.[63] Given the long history of the comorbidity of alcohol and nicotine use, the rising prevalence of e-cigarettes raises the question as to their role in the consumption of alcohol.[63] The use of nicotine enhances the pleasurable effects felt during alcohol consumption and increases cravings for it.[63]

E-cigarette users have an increased risk of alcohol misuse, such as binge drinking or chronic use, when compared with non-e-cigarette users.[63] Although fundamentally different, it has been suggested that the body's response to e-cigarette use may be similar to that of cigarettes with a few unique differences.[63] Alcohol interferes with normal innate lung immunity, particularly the physical barriers and cellular functions.[63] The metabolism of alcohol produces acetaldehyde, superoxide compounds, hydrogen radicals, and hydrogen peroxides, further promoting lipid peroxidation and generation of malondialdehyde and 4-Hydroxynonenal.[63] Chronic alcohol consumption is associated with bacterial pneumonia, viral lung infections such as respiratory syncytial virus, and accumulation of fluid in the lungs due to epithelial barrier dysfunction as seen in acute respiratory distress syndrome.[63]

The use of e-cigarettes has potentially pathogenic health effects on the lungs.[63] Cell types, including human fibroblasts, neutrophils, airway epithelial cells, human embryonic stem cells, and mouse neural stem cells, demonstrate morphological changes, even displaying cytotoxicity in stem cells and fibroblasts when exposed to undiluted e-liquid and flavor aldehydes.[63] E-cigarette use impairs physical barriers in the innate immune system of the lungs.[63] E-cigarette decrease cilia, potentially as a result of ROS production.[63] Similarly, excessive amounts of alcohol blunt cilia responses.[63] In combination, s-cigarettes with alcohol use disorder may further slow CBF similar to that of cigarettes and alcohol, leading to an impaired ability to clear pathogens and debris from the airway.[63] While it has not been investigated, alcohol use disorder may exacerbate the COPD-related symptoms seen in e-cigarette users.[63] A 2020 review hypothesizes that dual use of e-cigarette and alcohol may interfere with normal lung function, may contribute to the pathogenesis of COPD-like illnesses greater than single-substance users, and leave the dual user more susceptible to bacterial and viral infection.[63]

Addiction and dependence

Nicotine is highly addictive and can harm brain development, which continues until about age 25.[16] Pod mods contain high concentrations of nicotine that can lead to nicotine dependence.[17] A 2021 review found that "The speed of delivery to the bloodstream and the relative physical tolerability of vaping compared with smoking may engender higher blood nicotine levels and greater symptoms of nicotine dependence."[64] Pod mods effectively delivers nicotine and as a result magnifies the chance of nicotine dependence among minors.[18]

Minors using pod mods are more likely than traditional e-cigarette users to exhibit higher nicotine dependence symptoms.[18] Early use of nicotine has the cability to induce neurological alterations that give rise to higher intensity of dependence symptoms and increased drug use.[18] Nicotine dependence may enhance susceptibility to different kinds of tobacco marketing.[18] Nicotine dependence may also enhance peer or social pressures that encourage utilizing different kinds of tobacco products.[18] Teens may find it hard to interpret the amount of nicotine they are getting from a vape liquid, and this may result in greater nicotine use and subsequent nicotine addiction.[38] The potential for a continued life-long addiction to nicotine among minors is a significant public health concern.[18]

A 2022 review states that, "Although marketed as a smoking cessation tool, nicotine delivery through e-cigarettes can result in higher levels of nicotine in serum when compared to traditional tobacco cigarettes. For example, a recent study in rats compared the serum levels of nicotine after exposure to e-vapor (JUUL and previous generation e-cigarettes) versus CS (Marlboro Red cigarettes, produced by Philip Morris USA Inc.). JUUL e-vapor delivered 136.4 ng/ml of nicotine, which is substantially higher than the 17.1 ng/ml delivered by other e-cigarettes and 26.1 ng/ml delivered by Marlboro cigarettes. This study concluded that e-cigarettes are not safer than traditional cigarettes."[65]

History

In June 2015, Juul introduced a pod mod device.[35] British American Tobacco stated that they have been using nicotine salts in their US Vuse e-liquid brand since 2012.[41] Solace Technologies started selling nicotine salts in 2015.[67] It was reported in 2017 that Philip Morris International is developing an e-cigarette called STEEM that uses nicotine salts.[68] R. J. Reynolds Vapor Company launched in 2018 a pod mod device similar to Juul's device called Vuse Alto.[69]

Juul had a dominant market position by 2018, accounting for more than 70% of US e-cigarette sales.16 17 18 During this time, overall US sales of e-cigarettes doubled, with Juul being responsible for the bulk of market growth.[70] The popularity of the Juul pod system has led to a flood of other pod devices hitting the market.[71] There has been a proliferation of pod-based products with high nicotine concentration, triggered by Juul's financial success.[25] As of September 2018, there were no less than 39 similar Juul devices as well as 15 Juul-compatible pods being offered.[25]

Altria, manufacturer of Marlboro, announced in 2018 that it would halt sales of MarkTen Elite and MarkTen Apex due to concerns that vaping is proliferating in use among children.[72] In December 2018, Altria announced that it would cease selling all of its e-cigarette products.[73] Atria announced in December 2018 that it would buy a 35% stake in Juul for $12.8 billion.[74]

An organization named Parents Against Vaping E-cigarettes was started by frustrated parents whose children were using Juul.[75] The origination deployed activists in the majority of US states to push for anti-vaping laws and affect policy discussions with respect to vaping in city halls and statehouses.[75]

On June 23, 2022, the US FDA issued marketing denial orders (MDOs) to Juul Labs Inc. for all of their products currently marketed in the United States.[76] As a result, the company must stop selling and distributing these products.[76] After reviewing the company’s premarket tobacco product applications (PMTAs), the US FDA determined that the applications lacked sufficient evidence regarding the toxicological profile of the products to demonstrate that marketing of the products would be appropriate for the protection of the public health.[76] In particular, some of the company's study findings raised concerns due to insufficient and conflicting data – including regarding genotoxicity and potentially harmful chemicals leaching from the company's proprietary e-liquid pods – that have not been adequately addressed and precluded the FDA from completing a full toxicological risk assessment of the products named in the company's applications.[76] "The FDA is tasked with ensuring that tobacco products sold in this country meet the standard set by the law, but the responsibility to demonstrate that a product meets those standards ultimately falls on the shoulders of the company," said Michele Mital, acting director of the FDA's Center for Tobacco Products.[76] "As with all manufacturers, Juul had the opportunity to provide evidence demonstrating that the marketing of their products meets these standards. However, the company did not provide that evidence and instead left us with significant questions. Without the data needed to determine relevant health risks, the FDA is issuing these marketing denial orders."[76]

On June 24, 2022, the US Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit entered a temporary administrative stay of the marketing denial order for Juul Labs Inc.[76] The court notes the purpose of this administrative stay is to give the court sufficient opportunity to consider petitioner's forthcoming emergency motion for stay pending court review and should not be construed in any way as a ruling on the merits of that motion.[76] On June 27, 2022, Juul requested that the US Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit to put on hold for what it believed was an "extraordinary and unlawful" decision by the US FDA when earlier in the month it ruled the company to refrain from selling its vaping products.[77]

In response to the US FDA trying to ban Juul products from the US market, Karen E. Knudsen, CEO of the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, stated in part, "In the time Juul products were on the market unregulated, these products and Juul’s marketing strategies significantly contributed to the youth e-cigarette crisis we currently face in this nation and led to new, previously unimaginable, levels of addiction among youth. Given research shows youth who use e-cigarettes are more likely to use combustible cigarettes, preventing youth addiction to these products is critical to preventing tobacco-related cancers."[78]

Puff Bar, which was founded in 2019, offered disposable devices in excess of 20 flavors.[79] Building on its initial success, they added a range of flavored pods named Puff Krush.[79] Elf Bar began offering pod mod devices in 2022.[80]

Black market pod mod products

There is a flourishing illicit market for pod mods.[81]

Sales to youth

Many youth purchase Juul pod products from illicit sources because they are underage.[45]

Regulation

Amid the epidemic levels of youth use of e-cigarettes and the popularity of certain products among children, the US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) on January 20, 2020 issued a policy prioritizing enforcement against certain unauthorized flavored e-cigarette products that appeal to kids, including fruit and mint flavors.[82] Under this policy, companies that do not cease manufacture, distribution and sale of unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes (other than tobacco or menthol) within 30 days risk US FDA enforcement actions.[82] Beginning 30 days from the date of January 20, 2020 of the notice of availability of this guidance in the Federal Register, the US FDA intends to prioritize enforcement against these illegally marketed ENDS products by focusing on the following groups of products that do not have premarket authorization: Any flavored, cartridge-based ENDS product (other than a tobacco- or menthol-flavored ENDS product); All other ENDS products for which the manufacturer has failed to take (or is failing to take) adequate measures to prevent minors' access; and Any ENDS product that is targeted to minors or likely to promote use of ENDS by minors.[82] Cartridge-based ENDS products are a type of ENDS product that consists of, includes, or involves a cartridge or pod that holds liquid that is to be aerosolized when the product is used.[82] For purposes of this policy, a cartridge or pod is any small, enclosed unit (sealed or unsealed) designed to fit within or operate as part of an ENDS product.[82]

There is a limit on the nicotine content, meaning the nicotine strength of e-liquid cannot exceed 20 mg/ml (2.0%), while refillable e-liquids cannot exceed 10 ml in the UK.[83] Refill liquids in the EU with more than 20 mg/ml of nicotine may be sold with prior authorization from the pharmaceutical regulation.[84]

Marketing

Marketing efforts on social media benefited pod mods to control 72% of the US vaping market in 2018.[7] Advertisements state nicotine salt liquids contain 2 to 10 times more nicotine than those found in the majority of regular e-cigarette products.[5] Pod mods are heavily marketed, with a particular focus in the way youth can use them discreetly.[26] A marketing strategy is offering youth "skins" to personalize their pod mod.[85] "Skins" are customizable adhesive covers similar to mobile-phone cases.[5] In August 2017, a Twitter advertisement for Juul's "creme brulee" pods suggested to people to retweet it if they savored the "dessert without the spoon."[86] Every pod mod brand promotes a range of flavors.[87] Pod mods have been promoted using celebrity endorsements and social influencers.[18]

The US FDA sent a warning letter in June 2019 to Solace Technologies for failure to include the required nicotine warning statement for their Solace Vapor e-liquid products that were being promoted on social media on their behalf.[88] Under 21 C.F.R. § 1143.3, labeling and advertising for cigarette tobacco, roll-your-own tobacco, and covered tobacco products (other than cigars), such as e-liquid products, must bear the following warning statement: "WARNING: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical."[89] It also is unlawful for such tobacco product manufacturer, packager, importer, distributor, or retailer of the tobacco product to advertise or cause to be advertised within the US any tobacco product unless each advertisement bears the required warning statement (21 C.F.R. § 1143.3(b)).[89] Because labeling and/or advertising in the social media posts on behalf of the firm regarding these e-liquid products do not include the required nicotine warning statement for these products, in violation of 21 C.F.R. § 1143.3(a) and/or 21 C.F.R. § 1143.3(b), the e-liquid products are misbranded under section 903(a)(7)(B) of the FD&C Act (21 U.S.C. § 387c(a)(7)(B)).[89]

Advertised nicotine concentration in the liquid pod is not necessarily the same as in the vapor; furthermore, the gaseous phase may contain dangerous substances not reported on the packaging, such as ultrafine particles of propylene glycol, glycerin, and diacetin.[2]

Environmental impact

A garbology study of environmental contamination including ce-cigarette product waste was conducted at 12 public high schools in Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, and San Francisco counties in California.[90] At each school, researchers systematically scanned the student parking lots and exterior school perimeter areas once during July 2018–April 2019 to collect all e-cigarette product waste, combustible tobacco product waste, and cannabis product waste found on the ground.[90]

Overall, 893 waste items were collected, including 172 (19%) e-cigarette product waste items (nearly all were Juul or Juul-compatible pods and pod caps).[90] Additional scans were conducted at one upper-income area school beginning three months after Juul Labs announced it was removing flavors (except Cool Mint and Classic Menthol) from retail distribution.[90] These additional scans yielded 127 mint, 20 mango, four fruit Juul or Juul-compatible pod caps, and three yellow (banana or mango) Juul-compatible caps.[90]

Other names

Pod mods[24] are variously known as pod-mods,[91] pod-mod devices,[92] pod-Mod e-cigarette products,[93] pod-Mod e-cigarettes,[93] pod-based electronic cigarettes,[18] pod-based e-cigarettes,[18] pod-based nicotine e-cigarettes,[18] pod-based devices,[94] pod-based products,[18] pod products,[15] pod systems,[95] "pod" e-cigarettes,[96] pod ecigs,[18] pod ENDS,[97] pod vaping devices,[97] pod vape devices,[97] pod vapes,[98] or vape pods.[99]

Other devices

E-cigarettes come in a variety of devices including cigarette-like pens, pipes, hookahs, and tanks to simulate a smoking-type experience.[100] The size, shape, and design of later types of e-cigarettes do not emulate the smoking-type experience of traditional cigarettes.[30]

Gallery

- E-cigarette related images and media

-

Robbing the Future - Advertising Aimed at Children.

-

E-cigarettes - An Emerging Public Health Challenge.

-

Tobacco Use By Youth Is Rising – February 2019 – Vital Signs.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Prochaska, Judith J.; Vogel, Erin A.; Benowitz, Neal (1 August 2022). "Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod". Tobacco Control. 31 (e1): e88–e93. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056367. PMC 8460696. PMID 33762429.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Luca, Alina-Costina; Curpăn, Alexandrina-Ștefania; Iordache, Alin-Constantin; Mîndru, Dana Elena; Țarcă, Elena; Luca, Florin-Alexandru; Pădureț, Ioana-Alexandra (8 February 2023). "Cardiotoxicity of Electronic Cigarettes and Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco Products—A Problem for the Modern Pediatric Cardiologist". Healthcare. 11 (4): 491. doi:10.3390/healthcare11040491. PMC 9957306. PMID 36833024.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmc=value (help) This article incorporates text by Alina-Costina Luca, Alexandrina-Ștefania Curpăn, Alin-Constantin Iordache, Dana Elena Mîndru, Elena Țarcă, Florin-Alexandru Luca, Ioana-Alexandra Pădureț available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Alina-Costina Luca, Alexandrina-Ștefania Curpăn, Alin-Constantin Iordache, Dana Elena Mîndru, Elena Țarcă, Florin-Alexandru Luca, Ioana-Alexandra Pădureț available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Voos, Natalie; Goniewicz, Maciej L.; Eissenberg, Thomas (2019). "What is the nicotine delivery profile of electronic cigarettes?". Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 16 (11): 1193–1203. doi:10.1080/17425247.2019.1665647. ISSN 1742-5247. PMC 6814574. PMID 31495244.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Goniewicz, Maciej Lukasz; Boykan, Rachel; Messina, Catherine R; Eliscu, Alison; Tolentino, Jonatan (2018). "High exposure to nicotine among adolescents who use Juul and other vape pod systems ('pods')". Tobacco Control. 28 (6): tobaccocontrol–2018–054565. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054565. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6453732. PMID 30194085.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 Barrington-Trimis, Jessica L.; Leventhal, Adam M. (2018). "Adolescents' Use of "Pod Mod" E-Cigarettes — Urgent Concerns". New England Journal of Medicine. 379 (12): 1099–1102. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1805758. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 30134127.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Rachel Becker (6 May 2019). "Vaping technology 101: The latest trends in a growing industry". Toronto Sun.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Spindle, Tory R.; Eissenberg, Thomas (2018). "Pod Mod Electronic Cigarettes—An Emerging Threat to Public Health". JAMA Network Open. 1 (6): e183518. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3518. ISSN 2574-3805. PMID 30646245.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Galstyan, Ellen; Galimov, Artur; Sussman, Steve (2018). "Commentary: The Emergence of Pod Mods at Vape Shops". Evaluation & the Health Professions. 42 (1): 118–124. doi:10.1177/0163278718812976. ISSN 0163-2787. PMC 6637958. PMID 30477337.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Bonilla, Alex; Blair, Alexander J.; Alamro, Suliman M.; Ward, Rebecca A.; Feldman, Michael B.; Dutko, Richard A.; Karagounis, Theodora K.; Johnson, Adam L.; Folch, Erik E.; Vyas, Jatin M. (2019). "Recurrent spontaneous pneumothoraces and vaping in an 18-year-old man: a case report and review of the literature". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 13 (1): 283. doi:10.1186/s13256-019-2215-4. ISSN 1752-1947. PMC 6732835. PMID 31495337.

This article incorporates text by Alex Bonilla, Alexander J. Blair, Suliman M. Alamro, Rebecca A. Ward, Michael B. Feldman, Richard A. Dutko, Theodora K. Karagounis, Adam L. Johnson, Erik E. Folch, and Jatin M. Vyas available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Alex Bonilla, Alexander J. Blair, Suliman M. Alamro, Rebecca A. Ward, Michael B. Feldman, Richard A. Dutko, Theodora K. Karagounis, Adam L. Johnson, Erik E. Folch, and Jatin M. Vyas available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Vaping Related Lung Illness: A Summary of the Public Health Risks and Recommendations for the Public". California Tobacco Control Program. California Department of Public Health. 26 September 2019. pp. 1–5.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Cunningham, Aimee (23 October 2018). "Teens use Juul e-cigarettes much more often than other vaping products". Science News.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Boykan, Rachel; Messina, Catherine R.; Chateau, Gabriela; Eliscu, Allison; Tolentino, Jonathan; Goniewicz, Maciej L. (2019). "Self-Reported Use of Tobacco, E-cigarettes, and Marijuana Versus Urinary Biomarkers". Pediatrics. 143 (5): e20183531. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3531. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 31010908.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 Fadus, Matthew C.; Smith, Tracy T.; Squeglia, Lindsay M. (2019). "The rise of e-cigarettes, pod mod devices, and JUUL among youth: Factors influencing use, health implications, and downstream effects". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 201: 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.011. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 7183384. PMID 31200279.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Kava, Christine M.; Soule, Eric K.; Seegmiller, Laura; Gold, Emily; Snipes, William; Westfield, Taya; Wick, Noah; Afifi, Rima (2020). ""Taking Up a New Problem": Context and Determinants of Pod-Mod Electronic Cigarette Use Among College Students". Qualitative Health Research. 31 (4): 703–712. doi:10.1177/1049732320971236. ISSN 1049-7323. PMC 7878307. PMID 33213262.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Jenssen, Brian P.; Boykan, Rachel (2019). "Electronic Cigarettes and Youth in the United States: A Call to Action (at the Local, National and Global Levels)". Children. 6 (2): 30. doi:10.3390/children6020030. ISSN 2227-9067. PMC 6406299. PMID 30791645.

This article incorporates text by Brian P. Jenssen and Rachel Boykan available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Brian P. Jenssen and Rachel Boykan available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 "E-cigarettes Shaped Like USB Flash Drives: Information for Parents, Educators and Health Care Providers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 23 April 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Leslie, Frances M. (2020). "Unique, long-term effects of nicotine on adolescent brain". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 197: 173010. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2020.173010. ISSN 0091-3057. PMC 7484459. PMID 32738256.

- ↑ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 18.11 18.12 18.13 18.14 Lee, Stella Juhyun; Rees, Vaughan W.; Yossefy, Noam; Emmons, Karen M.; Tan, Andy S. L. (1 July 2020). "Youth and Young Adult Use of Pod-Based Electronic Cigarettes From 2015 to 2019". JAMA Pediatrics. 174 (7): 714. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0259. ISSN 2168-6203. PMC 7863733. PMID 32478809.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 Galper Grossman, Sharon (2019). "Vape Gods and Judaism—E-cigarettes and Jewish Law". Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal. 10 (3): e0019. doi:10.5041/RMMJ.10372. ISSN 2076-9172. PMC 6649778. PMID 31335312.

This article incorporates text by Sharon Galper Grossman available under the CC BY 3.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Sharon Galper Grossman available under the CC BY 3.0 license.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Chaturvedi, Pankaj; Mishra, Aseem; Datta, Sourav; Sinukumar, Snita; Joshi, Poonam; Garg, Apurva (2015). "Harmful effects of nicotine". Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. 36 (1): 24. doi:10.4103/0971-5851.151771. ISSN 0971-5851. PMC 4363846. PMID 25810571.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Mravec, Boris; Tibensky, Miroslav; Horvathova, Lubica; Babal, Pavel (2020). "E-Cigarettes and Cancer Risk". Cancer Prevention Research. 13 (2): 137–144. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-19-0346. ISSN 1940-6207. PMID 31619443.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Bracken-Clarke, Dara; Kapoor, Dhruv; Baird, Anne Marie; Buchanan, Paul James; Gately, Kathy; Cuffe, Sinead; Finn, Stephen P. (2021). "Vaping and lung cancer – A review of current data and recommendations". Lung Cancer. 153: 11–20. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.12.030. ISSN 0169-5002. PMID 33429159.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 LaVito, Angelica; Shama, Elijah (24 September 2019). "CDC warns of dangers of nicotine salts used by vaping giant Juul in e-cigarettes". CNBC.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Weedston, Lindsey (8 April 2019). "FDA To Investigate Whether Vaping Causes Seizures". The Fix.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Jackler, Robert K; Ramamurthi, Divya (2019). "Nicotine arms race: JUUL and the high-nicotine product market". Tobacco Control. 28 (6): tobaccocontrol–2018–054796. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054796. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 30733312.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Jenssen, Brian P.; Wilson, Karen M. (2019). "What is new in electronic-cigarettes research?". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 31 (2): 262–266. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000741. ISSN 1040-8703. PMC 6644064. PMID 30762705.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Walley, Susan C.; Wilson, Karen M.; Winickoff, Jonathan P.; Groner, Judith (2019). "A Public Health Crisis: Electronic Cigarettes, Vape, and JUUL". Pediatrics. 143 (6): e20182741. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2741. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 31122947.

- ↑ "Commentaries on Viewpoint: Pod-mod vs. conventional e-cigarettes: nicotine chemistry, pH, and health effects". Journal of Applied Physiology. 128 (4): 1059–1062. 2020. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00131.2020. ISSN 8750-7587. PMID 32283999.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Virgili, Fabrizio; Nenna, Raffaella; Ben David, Shira; Mancino, Enrica; Di Mattia, Greta; Matera, Luigi; Petrarca, Laura; Midulla, Fabio (December 2022). "E-cigarettes and youth: an unresolved Public Health concern". Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 48 (1): 97. doi:10.1186/s13052-022-01286-7. PMC 9194784. PMID 35701844.

This article incorporates text by Fabrizio Virgili, Raffaella Nenna, Shira Ben David, Enrica Mancino, Greta Di Mattia, Luigi Matera, Laura Petrarca, and Fabio Midulla available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Fabrizio Virgili, Raffaella Nenna, Shira Ben David, Enrica Mancino, Greta Di Mattia, Luigi Matera, Laura Petrarca, and Fabio Midulla available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Stefaniak, Aleksandr B.; LeBouf, Ryan F.; Ranpara, Anand C.; Leonard, Stephen S. (2021). "Toxicology of flavoring- and cannabis-containing e-liquids used in electronic delivery systems". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 224: 107838. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107838. ISSN 0163-7258. PMC 8251682. PMID 33746051.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Brody, Jane E. (23 November 2020). "The Risks of Another Epidemic: Teenage Vaping". The New York Times.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Gordon, Terry; Karey, Emma; Rebuli, Meghan E.; Escobar, Yael-Natalie H.; Jaspers, Ilona; Chen, Lung Chi (6 January 2022). "E-Cigarette Toxicology". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 62 (1): 301–322. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-042921-084202. PMC 9386787. PMID 34555289.

- ↑ Craver, Richard (13 June 2022). "FDA issues another limited authorization of e-cigarette products". Winston-Salem Journal.

- ↑ Craver, Richard (20 September 2022). "Vuse expands e-cigarette market share lead over Juul to double digits". Winston-Salem Journal.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 McKelvey, Karma; Baiocchi, Mike; Halpern-Felsher, Bonnie (2018). "Adolescents' and Young Adults' Use and Perceptions of Pod-Based Electronic Cigarettes". JAMA Network Open. 1 (6): e183535. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3535. ISSN 2574-3805. PMC 6324423. PMID 30646249.

- ↑ Civiletto, Cody W.; Hutchison, Julia (January 2023). "Electronic Vaping Delivery Of Cannabis And Nicotine". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31424744.

- ↑ Chen, Angus (4 December 2017). "Teenagers Embrace JUUL, Saying It's Discreet Enough To Vape In Class". NPR.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Overbeek, Daniel L.; Kass, Alexandra P.; Chiel, Laura E.; Boyer, Edward W.; Casey, Alicia M. H. (2 July 2020). "A review of toxic effects of electronic cigarettes/vaping in adolescents and young adults". Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 50 (6): 531–538. doi:10.1080/10408444.2020.1794443. ISSN 1040-8444. PMID 32715837.

- ↑ Besaratinia, Ahmad; Tommasi, Stella (2021). "The consequential impact of JUUL on youth vaping and the landscape of tobacco products: The state of play in the COVID-19 era". Preventive Medicine Reports. 22: 101374. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101374. ISSN 2211-3355. PMC 8207461. PMID 34168950.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Hamann, Stephen L.; Kungskulniti, Nipapun; Charoenca, Naowarut; Kasemsup, Vijj; Ruangkanchanasetr, Suwanna; Jongkhajornpong, Passara (22 September 2023). "Electronic Cigarette Harms: Aggregate Evidence Shows Damage to Biological Systems". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 20 (19): 6808. doi:10.3390/ijerph20196808. PMC 10572885. PMID 37835078.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmc=value (help) This article incorporates text by Stephen L Hamann, Nipapun Kungskulniti, Naowarut Charoenca, Vijj Kasemsup, Suwanna Ruangkanchanasetr, and Passara Jongkhajornpongs available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Stephen L Hamann, Nipapun Kungskulniti, Naowarut Charoenca, Vijj Kasemsup, Suwanna Ruangkanchanasetr, and Passara Jongkhajornpongs available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 41.5 Rachel Becker (21 November 2018). "Juul's nicotine salts are dominating the market — and other companies want in". The Verge.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 "E-cigarette, or vaping, products visual dictionary" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 13 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Julia Belluz (1 May 2018). "Juul, the vape device teens are getting hooked on, explained". Vox.

- ↑ Casey, Alicia M; Muise, Eleanor D; Crotty Alexander, Laura E (2020). "Vaping and e-cigarette use. Mysterious lung manifestations and an epidemic". Current Opinion in Immunology. 66: 143–150. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2020.10.003. ISSN 0952-7915. PMC 7755270. PMID 33186869.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 John-Anthony Fraga (19 September 2019). "The Dangers of Juuling". National Center for Health Research.

- ↑ O’Connell, Grant; Pritchard, John D.; Prue, Chris; Thompson, Joseph; Verron, Thomas; Graff, Donald; Walele, Tanvir (2019). "A randomised, open-label, cross-over clinical study to evaluate the pharmacokinetic profiles of cigarettes and e-cigarettes with nicotine salt formulations in US adult smokers". Internal and Emergency Medicine. 14 (6): 853–861. doi:10.1007/s11739-019-02025-3. ISSN 1828-0447. PMC 6722145. PMID 30712148.

This article incorporates text by Grant O'Connell, John D. Pritchard, Chris Prue, Joseph Thompson, Thomas Verron, Donald Graff, and Tanvir Walele available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Grant O'Connell, John D. Pritchard, Chris Prue, Joseph Thompson, Thomas Verron, Donald Graff, and Tanvir Walele available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ Lee Johnson (22 September 2017). "Nicotine salts: more satisfying experience or marketing ploy?". Vaping360. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018.

- ↑ Breland, Alison; McCubbin, Andrea; Ashford, Kristin (2019). "Electronic nicotine delivery systems and pregnancy: Recent research on perceptions, cessation, and toxicant delivery". Birth Defects Research. 111 (17): 1284–1293. doi:10.1002/bdr2.1561. ISSN 2472-1727. PMID 31364280.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Snoderly, Hunter T.; Nurkiewicz, Timothy R.; Bowdridge, Elizabeth C.; Bennewitz, Margaret F. (18 November 2021). "E-Cigarette Use: Device Market, Study Design, and Emerging Evidence of Biological Consequences". International journal of molecular sciences. MDPI AG. 22 (22): 12452. doi:10.3390/ijms222212452. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 8619996. PMID 34830344.

This article incorporates text by Hunter T. Snoderly, Timothy R. Nurkiewicz, Elizabeth C. Bowdridge, and Margaret F. Bennewitz available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Hunter T. Snoderly, Timothy R. Nurkiewicz, Elizabeth C. Bowdridge, and Margaret F. Bennewitz available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ Eissenberg, Thomas; Bhatnagar, Aruni; Chapman, Simon; Jordt, Sven-Eric; Shihadeh, Alan; Soule, Eric K. (2020). "Invalidity of an Oft-Cited Estimate of the Relative Harms of Electronic Cigarettes". American Journal of Public Health. 110 (2): 161–162. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305424. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 6951374. PMID 31913680.

- ↑ Hamberger, Eric Stephen; Halpern-Felsher, Bonnie (June 2020). "Vaping in adolescents: epidemiology and respiratory harm". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 32 (3): 378–383. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000896. PMID 32332328.

- ↑ Choi, Humberto; Lin, Yu; Race, Elliot; Macmurdo, Maeve G. (February 2021). "Electronic Cigarettes and Alternative Methods of Vaping". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 18 (2): 191–199. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-511CME. PMID 33052707.

- ↑ "Statement from the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health on the increasing rates of youth vaping in Canada". Public Health Agency of Canada. 11 April 2019.

- ↑ "The 101 on E-cigarettes Infographic". American Heart Association. 2019.

- ↑ Baumgaertner, Emily (19 November 2019). "Juul wanted to revolutionize vaping. It took a page from Big Tobacco's chemical formulas". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Shao, Xuesi M.; Friedman, Theodore C. (2020). "Pod-mod vs. conventional e-cigarettes: nicotine chemistry, pH, and health effects". Journal of Applied Physiology. 128 (4): 1056–1058. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00717.2019. ISSN 8750-7587. PMID 31854246.

- ↑ Szumilas, Paweł; Wilk, Aleksandra; Szumilas, Kamila; Karakiewicz, Beata (6 February 2022). "The Effects of E-Cigarette Aerosol on Oral Cavity Cells and Tissues: A Narrative Review". Toxics. MDPI AG. 10 (2): 74. doi:10.3390/toxics10020074. ISSN 2305-6304. PMC 8878056. PMID 35202260.

This article incorporates text by Paweł Szumilas, Aleksandra Wilk, Kamila Szumilas, and Beata Karakiewicz available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Paweł Szumilas, Aleksandra Wilk, Kamila Szumilas, and Beata Karakiewicz available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ "JUUL®: An Electronic Cigarette You Should Know About". American Academy of Family Physicians. 2019.

- ↑ "Professor Testifies Before Congress on Youth Vaping". Boston University School of Public Health. 17 October 2019.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Hofmann, Joseph J.; Poulos, Victoria C.; Zhou, Jiahai; Sharma, Maksym; Parraga, Grace; McIntosh, Marrissa J. (24 January 2024). "Review of quantitative and functional lung imaging evidence of vaping-related lung injury". Frontiers in Medicine. 11. doi:10.3389/fmed.2024.1285361. PMC 10847544. PMID 38327710.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmc=value (help) This article incorporates text by Joseph J. Hofmann, Victoria C. Poulos, Jiahai Zhou, Maksym Sharma, Grace Parraga, and Marrissa J. McIntosh available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Joseph J. Hofmann, Victoria C. Poulos, Jiahai Zhou, Maksym Sharma, Grace Parraga, and Marrissa J. McIntosh available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 61.4 61.5 61.6 61.7 61.8 61.9 Espinoza-Derout, Jorge; Shao, Xuesi M.; Lao, Candice J.; Hasan, Kamrul M.; Rivera, Juan Carlos; Jordan, Maria C.; Echeverria, Valentina; Roos, Kenneth P.; Sinha-Hikim, Amiya P.; Friedman, Theodore C. (7 April 2022). "Electronic Cigarette Use and the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases". Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 9: 879726. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.879726. PMC 9021536. PMID 35463745.

This article incorporates text by Jorge Espinoza-Derout, Xuesi M. Shao, Candice J. Lao, Kamrul M. Hasan, Juan Carlos Rivera, Maria C. Jordan, Valentina Echeverria, Kenneth P. Roos, Amiya P. Sinha-Hikim, and Theodore C. Friedman available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Jorge Espinoza-Derout, Xuesi M. Shao, Candice J. Lao, Kamrul M. Hasan, Juan Carlos Rivera, Maria C. Jordan, Valentina Echeverria, Kenneth P. Roos, Amiya P. Sinha-Hikim, and Theodore C. Friedman available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ Garcia, Phoebe D.; Gornbein, Jeffrey A.; Middlekauff, Holly R. (December 2020). "Cardiovascular autonomic effects of electronic cigarette use: a systematic review". Clinical Autonomic Research. 30 (6): 507–519. doi:10.1007/s10286-020-00683-4. PMC 7704447. PMID 32219640.

This article incorporates text by Phoebe D. Garcia, Jeffrey A. Gornbein, and Holly R. Middlekauff available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Phoebe D. Garcia, Jeffrey A. Gornbein, and Holly R. Middlekauff available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ 63.00 63.01 63.02 63.03 63.04 63.05 63.06 63.07 63.08 63.09 63.10 63.11 63.12 63.13 63.14 63.15 63.16 63.17 63.18 Wetzel, Tanner J.; Wyatt, Todd A. (2020). "Dual Substance Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Alcohol". Frontiers in Physiology. 11. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.593803. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 7667127. PMID 33224040.

This article incorporates text by Tanner J Wetzel and Todd A Wyatt available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Tanner J Wetzel and Todd A Wyatt available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ Cahn, Zachary; Drope, Jeffrey; Douglas, Clifford E; Henson, Rosemarie; Berg, Carla J; Ashley, David L; Eriksen, Michael P (4 May 2021). "Applying the Population Health Standard to the Regulation of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 23 (5): 780–789. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntaa190.

- ↑ Esteban-Lopez, Maria; Perry, Marissa D.; Garbinski, Luis D.; Manevski, Marko; Andre, Mickensone; Ceyhan, Yasemin; Caobi, Allen; Paul, Patience; Lau, Lee Seng; Ramelow, Julian; Owens, Florida; Souchak, Joseph; Ales, Evan; El-Hage, Nazira (2022). "Health effects and known pathology associated with the use of E-cigarettes". Toxicology Reports. 9: 1357–1368. doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2022.06.006. PMC 9764206. PMID 36561957.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmc=value (help) - ↑ 66.0 66.1 Chu, Kar-Hai; Hershey, Tina B; Hoffman, Beth L; Wolynn, Riley; Colditz, Jason B; Sidani, Jaime E; Primack, Brian A (25 March 2022). "Puff Bars, Tobacco Policy Evasion, and Nicotine Dependence: Content Analysis of Tweets". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 24 (3): e27894. doi:10.2196/27894. PMC 8994141. PMID 35333188.

This article incorporates text by Kar-Hai Chu, Tina B Hershey, Beth L Hoffman, Riley Wolynn, Jason B Colditz, Jaime E Sidani, and Brian A Primack available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Kar-Hai Chu, Tina B Hershey, Beth L Hoffman, Riley Wolynn, Jason B Colditz, Jaime E Sidani, and Brian A Primack available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ Will Yakowicz (9 May 2018). "These 4 Guys Just Made $3.7 Million Selling Nicotine Salt Juice". Inc.

- ↑ Angelica LaVito (18 September 2017). "With tighter cigarette rules ahead, here's a peek inside Big Tobacco's pipeline". CNBC.

- ↑ Craver, Richard (25 August 2018). "Juul expands e-cig market share gap with Reynolds' Vuse". Winston-Salem Journal.

- ↑ Gotts, Jeffrey E; Jordt, Sven-Eric; McConnell, Rob; Tarran, Robert (30 September 2019). "What are the respiratory effects of e-cigarettes?". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). BMJ. 366: l5275. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5275. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 7850161. PMID 31570493.

This article incorporates text by Jeffrey E Gotts, Sven-Eric Jordt, Rob McConnel, and Robert Tarran available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Jeffrey E Gotts, Sven-Eric Jordt, Rob McConnel, and Robert Tarran available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ "JUUL copycats are flooding the e-cigarette market". Truth Initiative. August 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Marlboro maker axes flavoured e-cigarettes". BBC News. 25 October 2018.

- ↑ Jordan Crook (20 December 2018). "Juul Labs gets $12.8 billion investment from Marlboro Maker Altria Group". TechCrunch.

- ↑ "Altria Buys 35 Percent Stake In E-Cigarette Maker Juul". National Public Radio. 20 December 2018.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Lauren Etter (14 May 2021). "Juul Finds Hell Hath No Fury Like an Army of Really Rich Parents". Bloomberg News.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 76.4 76.5 76.6 76.7 "FDA Denies Authorization to Market JUUL Products". United States Food and Drug Administration. 23 June 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Ken Alltucker (27 June 2022). "Juul's appeal allows it to sell vaping devices, pods as federal court weighs FDA ban". USA Today.

- ↑ Dandurant, Karen (1 July 2022). "Seacoast experts call vaping 'gateway' to smoking for teens as FDA seeks Juul ban". Foster's Daily Democrat. Yahoo! Entertainment.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Kaplan, Sheila (2 June 2020). "Lawmakers Say Puff Bar Used Pandemic to Market to Teens". The New York Times.

- ↑ Leyland, Adam (16 December 2022). "How the ElfBar captured the hearts, minds and lungs of the Zoomer generation". The Grocer.

- ↑ Karen Zraick and Jacey Fortin (19 September 2019). "Vaping is big, but so are risks and unknowns: A look at the issues". The Seattle Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 "FDA finalizes enforcement policy on unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes that appeal to children, including fruit and mint". United States Department of Health and Human Services. United States Food and Drug Administration. 2 January 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "E-cigarettes: regulations for consumer products". GOV.UK. 2 November 2022.

- ↑ Famele, M.; Ferranti, C.; Abenavoli, C.; Palleschi, L.; Mancinelli, R.; Draisci, R. (2014). "The Chemical Components of Electronic Cigarette Cartridges and Refill Fluids: Review of Analytical Methods". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 17 (3): 271–279. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu197. ISSN 1462-2203. PMC 5479507. PMID 25257980.

- ↑ Ben Chandler and Pat Withrow (30 November 2018). "Opinion: New e-cigs pose serious health dangers". Cincinnati.com.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Erin Brodwin (26 November 2018). "See how Juul turned teens into influencers and threw buzzy parties to fuel its rise as Silicon Valley's favorite e-cig company". Business Insider.

- ↑ Delnevo, Cristine; Giovenco, Daniel P; Hrywna, Mary (2020). "Rapid proliferation of illegal pod-mod disposable e-cigarettes". Tobacco Control: tobaccocontrol-2019-055485. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055485. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 32001606.

- ↑ "Companies told to stop using social media influencers to promote vaping products". KSWB-TV. 7 June 2019.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 "Solace Technologies, LLC d/b/a Solace Vapor". United States Food and Drug Administration. 7 June 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 90.3 90.4 Mock, Jeremiah (2019). "Notes from the Field: Environmental Contamination from E-cigarette, Cigarette, Cigar, and Cannabis Products at 12 High Schools — San Francisco Bay Area, 2018–2019". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 68 (40): 897–899. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6840a4. PMC 6788397. PMID 31600185.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Leavens, Eleanor L. S.; Smith, Tracy T.; Natale, Noelle; Carpenter, Matthew J. (2020). "Electronic cigarette dependence and demand among pod mod users as a function of smoking status". Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 34 (7): 804–810. doi:10.1037/adb0000583. ISSN 1939-1501. PMC 7572426. PMID 32297753.

- ↑ Massey, Zachary B; Brockenberry, Laurel O; Murray, Tori E; Harrell, Paul T (2021). "Dripping Technology Use Among Young Adult E-Cigarette Users". Tobacco use insights. SAGE Publications. 14: 1179173X2110354. doi:10.1177/1179173x211035448. ISSN 1179-173X. PMC 8327010. PMID 34377042.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Leventhal, Adam M.; Goldenson, Nicholas I.; Cho, Junhan; Kirkpatrick, Matthew G.; McConnell, Rob S.; Stone, Matthew D.; Pang, Raina D.; Audrain-McGovern, Janet; Barrington-Trimis, Jessica L. (1 November 2019). "Flavored E-cigarette Use and Progression of Vaping in Adolescents". Pediatrics. 144 (5): e20190789. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-0789. PMID 31659004.

- ↑ Smith, Maxwell L.; Gotway, Michael B.; Crotty Alexander, Laura E.; Hariri, Lida P. (2020). "Vaping-related lung injury". Virchows Archiv. 478 (1): 81–88. doi:10.1007/s00428-020-02943-0. ISSN 0945-6317. PMC 7590536. PMID 33106908.

- ↑ Jenssen, Brian P.; Walley, Susan C. (2019). "E-Cigarettes and Similar Devices". Pediatrics. 143 (2): e20183652. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3652. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC 6644065. PMID 30835247.

- ↑ Hendlin, Yogi Hale; Bialous, Stella A. (January 2020). "The environmental externalities of tobacco manufacturing: A review of tobacco industry reporting". Ambio. 49 (1): 17–34. doi:10.1007/s13280-019-01148-3. PMC 6889105. PMID 30852780.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 Ling, Pamela M.; Kim, Minji; Egbe, Catherine O.; Patanavanich, Roengrudee; Pinho, Mariana; Hendlin, Yogi (1 March 2022). "Moving targets: how the rapidly changing tobacco and nicotine landscape creates advertising and promotion policy challenges". Tobacco Control. 31 (2): 222–228. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056552. PMID 35241592.

- ↑ Dave Kriegel (18 January 2018). "Mi-Pod by Smoking Vapor Review | Pocketable and Refillable". Vaping360. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018.

- ↑ Sidani, Jaime E.; Colditz, Jason B.; Barrett, Erica L.; Shensa, Ariel; Chu, Kar-Hai; James, A. Everette; Primack, Brian A. (2019). "I wake up and hit the JUUL: Analyzing Twitter for JUUL nicotine effects and dependence". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 204: 107500. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.005. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 6878169. PMID 31499242.

- ↑ Gilmore, Bretton; Reveles, Kelly; Frei, Christopher R. (1 December 2022). "Electronic cigarette or vaping use among adolescents in the United States: A call for research and legislative action". Frontiers in Public Health. 10: 1088032. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1088032. PMC 9752070. PMID 36530666.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmc=value (help) This article incorporates text by Bretton Gilmore, Kelly Reveles, and Christopher R. Frei available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Bretton Gilmore, Kelly Reveles, and Christopher R. Frei available under the CC BY 4.0 license.