Urumacotherium

| Urumacotherium | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Family: | †Mylodontidae |

| Genus: | †Urumacotherium Bocquentin-Villanueva 1983 |

| Type species | |

| †Urumacotherium garciai Bocquentin-Villanueva, 1983

| |

| Other species | |

| |

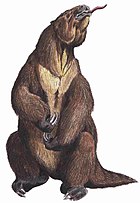

Urumacotherium (meaning "Urumaco beast") is an extinct genus of ground sloths of the family Mylodontidae. It lived from the Middle Miocene to the Early Pliocene of what is now Brazil, Peru and Venezuela.

Classification

Urumacotherium is an extinct genus of the also extinct family Mylodontidae. The Mylodontidae represent a branch of the suborder of sloths (Folivora). Within this they are often grouped together with the Orophodontidae and the Scelidotheriidae in the superfamily Mylodontoidea (sometimes, however, the Scelidotheriidae and the Orophodontidae are considered only as a subfamily of the Mylodontidae).[1] In a classical view, based on skeletal anatomical studies, the Mylodontoidea in turn represent one of the two major evolutionary lineages of sloths, along with the Megatherioidea. Molecular genetic studies and protein analyses assign a third to these two groups, the Megalocnoidea. Within the Mylodontoidea are the two-fingered sloths of the genus Choloepus, one of the two extant sloth genera.[2][3] The Mylodontidae form one of the most diverse groups within the sloths. Prominent features are found in their high-crowned teeth, which deviate from those of the Megatherioidea with a rather flat (lobate) occlusal surface. This is often associated with a greater adaptation to grassy foods. The posterior teeth have a round or oval cross-section, while the anteriormost have a canine-like design. The hind foot is also distinctly rotated so that the sole points inward.[4][5] Mylodonts appeared as early as the Oligocene, with Paroctodontotherium from Salla-Luribay in Bolivia among their earliest records.[6]

The internal division of the Mylodontidae is complex and much debated. Widely accepted are the late groups of the Mylodontinae with Mylodon as the type genus and the Lestodontinae, whose type genus is Lestodon but sometimes includes Paramylodon and Glossotherium (sometimes also listed as belonging to the tribes Mylodontini and Lestodontini).[7] The subdivision of the terminal group of mylodonts into the Lestodontinae and Mylodontinae found confirmation in one of the most comprehensive studies of the phylogeny of sloths based on cranial features in 2004,[8] which subsequently found multiple support.[9][10] However, a later analysis from 2019 doubts it again.[11] A higher-resolution phylogenetic study of the mylodonts published in the same year again supports the branching of terminal forms. According to this, the Mylodontinae and Lestodontinae can be distinguished on the basis of the canine anterior teeth. In the latter, these are large and separated from the posterior teeth by a long diastema; the former, on the other hand, have only small or partially reduced caniniform teeth, which are usually more closely apposed to the molar-like teeth.[12] Numerous other subfamilies have been established in the past, including, for example, the Nematheriinae for representatives from the Lower Miocene or the Octomylodontinae for all basal forms.[13] Their recognition varies mostly depending on the editor. Another group is found with the Urumacotheriinae, of which is named after Urumacotherium which were established only in 2004.[14] Their basic population is formed by the late Miocene representatives of northern South America. In principle, a revision is urged for the entire family, since numerous of the higher taxonomic units do not have a formal diagnosis.[15]

Below is a phylogenetic tree of the Mylodontidae, based on the work of Boscaini and colleagues (2019).[12]

References

- ^ Luciano Varela, P. Sebastián Tambusso, H. Gregory McDonald und Richard A. Fariña: Phylogeny, Macroevolutionary Trends and Historical Biogeography of Sloths: Insights From a Bayesian Morphological Clock Analysis. Systematic Biology 68 (2), 2019, S. 204–218

- ^ Frédéric Delsuc, Melanie Kuch, Gillian C. Gibb, Emil Karpinski, Dirk Hackenberger, Paul Szpak, Jorge G. Martínez, Jim I. Mead, H. Gregory McDonald, Ross D.E. MacPhee, Guillaume Billet, Lionel Hautier und Hendrik N. Poinar: Ancient mitogenomes reveal the evolutionary history and biogeography of sloths. Current Biology 29 (12), 2019, S. 2031–2042, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043

- ^ Samantha Presslee, Graham J. Slater, François Pujos, Analía M. Forasiepi, Roman Fischer, Kelly Molloy, Meaghan Mackie, Jesper V. Olsen, Alejandro Kramarz, Matías Taglioretti, Fernando Scaglia, Maximiliano Lezcano, José Luis Lanata, John Southon, Robert Feranec, Jonathan Bloch, Adam Hajduk, Fabiana M. Martin, Rodolfo Salas Gismondi, Marcelo Reguero, Christian de Muizon, Alex Greenwood, Brian T. Chait, Kirsty Penkman, Matthew Collins und Ross D. E. MacPhee: Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3, 2019, S. 1121–1130, doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z

- ^ H. Gregory McDonald und Gerardo de Iuliis: Fossil history of sloths. In: Sergio F. Vizcaíno und W. J. Loughry (Hrsg.): The Biology of the Xenarthra. University Press of Florida, 2008, S. 39–55.

- ^ H. Gregory McDonald: Evolution of the Pedolateral Foot in Ground Sloths: Patterns of Change in the Astragalus. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 19, 2012, S. 209–215

- ^ Bruce J. Shockey und Federico Anaya: Grazing in a New Late Oligocene Mylodontid Sloth and a Mylodontid Radiation as a Component of the Eocene-Oligocene Faunal Turnover and the Early Spread of Grasslands/Savannas in South America. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 18, 2011, S. 101–115

- ^ Malcolm C. McKenna und Susan K. Bell: Classification of mammals above the species level. Columbia University Press, New York, 1997, S. 1–631 (S. 94–96)

- ^ Timothy J. Gaudin: Phylogenetic relationships among sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): the craniodental evidence. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 140, 2004, S. 255–305

- ^ Ascanio D. Rincón, Andrés Solórzano, H. Gregory McDonald und Mónica Núñez Flores: Baraguatherium takumara, Gen. et Sp. Nov., the Earliest Mylodontoid Sloth (Early Miocene) from Northern South America. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 24 (2), 2017, S. 179–191

- ^ Luciano Brambilla und Damián Alberto Ibarra: Archaeomylodon sampedrinensis, gen. et sp. nov., a new mylodontine from the middle Pleistocene of Pampean Region, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 38 (6), 2018, S. e1542308, doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1542308

- ^ Luciano Varela, P. Sebastián Tambusso, H. Gregory McDonald und Richard A. Fariña: Phylogeny, Macroevolutionary Trends and Historical Biogeography of Sloths: Insights From a Bayesian Morphological Clock Analysis. Systematic Biology 68 (2), 2019, S. 204–218

- ^ a b Alberto Boscaini, François Pujos und Timothy J. Gaudin: A reappraisal of the phylogeny of Mylodontidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra) and the divergence of mylodontine and lestodontine sloths. Zoologica Scripta 48 (6), 2019, S. 691–710, doi:10.1111/zsc.12376

- ^ Andrés Rinderknecht, Enrique Bostelmann T., Daniel Perea und Gustavo Lecuona: A New Genus and Species of Mylodontidae (Mammalia: Xenarthra) from the Late Miocene of Southern Uruguay, with Comments on the Systematics of the Mylodontinae. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (3), 2010, S. 899–910

- ^ Francisco Ricardo Negri und Jorge Ferigolo: Urumacotheriinae, nova subfamília de Mylodontidae (Mammalia, Tardigrada) do Mioceno Superior-Plioceno, América do Sul. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 7 (2), 2004, S. 281–288

- ^ Ascanio D. Rincón, H. GregoryMcDonald, Andrés Solórzano, Mónica Núñez Flores und Damián Ruiz-Ramoni: A new enigmatic Late Miocene mylodontoid sloth from northern South America. Royal Society Open Science 2, 2015, S. 140256, doi:10.1098/rsos.140256

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with 'species' microformats

- Prehistoric sloths

- Miocene xenarthrans

- Miocene mammals of South America

- Pliocene xenarthrans

- Pliocene mammals of South America

- Fossil taxa described in 1983

- Neogene Peru

- Fossils of Peru

- Neogene Brazil

- Fossils of Brazil

- Neogene Venezuela

- Fossils of Venezuela

- Prehistoric placental genera