Talk:Paraphyly

| This article is rated C-class on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| On 27 October 2023, it was proposed that this article be moved to Paraphyletic groups. The result of the discussion was withdrawn by nominator. |

Unclear text

In biological taxonomy, a grouping of organisms is said to be paraphyletic if it does not represent all the descendants of some common ancestor. Most schools of taxonomy advocate that groups reflect phylogeny instead, and so view the existence of paraphyletic groups in a classification as errors. Taxonomic groups that do share a common ancestor are called monophyletic.

- I'm a little confused here. The last sentence seems to indicate monophyletic means "all share a common ancestor", but the first sentence seems to indicate that paraphyletic means "does not provide complete coverage of the set of all descendants of some common ancestor". Is the first sentence instead intended to mean "contains members which may not all share the same set of ancestors"? Chas zzz brown 11:21 Dec 6, 2002 (UTC)

- Thanks for the clarification, Steve Chas zzz brown 07:51 Feb 12, 2003 (UTC)

This does not necessarily mean that older biologists meant to create them; more often it was just that they needed to have some taxonomy in order to organize the huge number of species in a way they could understand, and without modern scientific evidence, guesswork was required that later turned out to be wrong.

I don't think this is true. Older taxonomies in many cases contain groups which are obviously intended to be paraphyletic. For instance, it has long been understood that mammals and birds evolved from reptiles (making the reptiles paraphyletic), but only recently has the class Reptilia been objected to on these grounds.

- I really did not like that paragraph but wondered how best to change it. The most charitable interpretation of it seems to be at the genus level, where many paraphyletic genera have been erected because of they have been classified by overall similarity, which necessarily includes plesiomorphies, rather than by recognizing apomorphies by a cladistic analysis.

In phylogenetics, a grouping of organisms is said to be paraphyletic if all the members of the group have a common ancestor but the group does not include all the descendants of the common ancestor.

This is a tautology, any group of organisms is vacuously paraphyletic as defined here (let A be a common ancestor, let B be a parent of A, and let C be a sibling of A sharing parent B. Then C is not in the group, but it is the descendent of a common ancestor of the group, namely B). It should probably read "In phylogenetics, a grouping of organisms is said to be paraphyletic if the group does not include all of the descendents of the most recent common ancestor of all the members." I would change the page but I don't want to introduce an error, in case this isn't what the author intended to say. --A5 00:25, 26 Mar 2004 (UTC)

Another confused reader here... what does this mean?

- Groups which include all the descendants of a common ancestor are commonly termed monophyletic, although this term is sometimes taken to apply to paraphyletic groups as well, in which case they are called holophyletic.

The primary culprit is the unclear "they", but the whole sentence is as clear as mud. Should probably be broken into two carefully worded sentences. Perhaps it would be better to have three parallel definitions: paraphyletic, monophyletic, holophyletic, to make it clearer exactly how they're used and what the distinctions are. I'm not a science dunce, I promise! This just needs refining. [[User:CatherineMunro|Catherine\talk]] 07:06, 28 Nov 2004 (UTC)

A5 is exactly right, the definition as it was made no sense:

- In phylogenetics, a grouping of organisms is said to be paraphyletic if all the members of the group have a common ancestor but the group does not include all the descendants of the common ancestor.

To see why this makes no sense, consider this: some amphibian is a common ancestor for all members of Mammalia. Yet all reptiles are also descendants of this same amphibian, and therefore by this definition Mammalia is paraphyletic.

You can generalize the conclusion to any group, which shows the definition is obviously broken.

I'm not a biologist, but I would rather leave a definition that I believe to be correct than one I know to be wrong. (You know, Be bold). So I've made the change, feel free to comment. --Saforrest 00:35, Jan 28, 2005 (UTC)

- the class Reptilia as traditionally defined is paraphyletic because that class does not include birds (class Aves), which are descended from reptiles.

This is not a good example since birds almost certainly came from warm-blooded dinosaurs, not reptiles. I haven’t changed it because a better example should be substituted. But someone should. David Shear, Oct 14, 2005.

- Two points to this; classic Reptilia includes dinosaurs; how to reorganise the major subdivisions of Amniota is not something there is a clear agreement on, but promoting Dinosauria to the same level as Reptilia, Aves and Mammalia is not the only possibility. Second point, how about using apes as the example? - humans are descended from apes but not included amongst them. Of course, this could be on the creationist-avoidance principle Richard Gadsden 00:41, 23 September 2006 (UTC)

Birds are now considered to be part of Reptilia, I would delete that diagram if I knew how. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Tylersquare (talk • contribs) 18:51, 25 November 2008 (UTC)

Paraphyly in linguistics?

I have removed the paragraph "The term paraphyletic is also used in historical linguistics, with similar meaning. For example, there are scholars who believe that centum and satem are paraphyletic groups of Indo-European languages". It is so because these terms are not believed (by some linguists) to be paraphyletic but polyphyletic rather. See Talk:Indo-European languages for details. --Grzegorj 16:55, 23 August 2005 (UTC)

The term is used in several Wiki articles on various languages, however.17:51, 29 November 2007 (UTC) —Preceding unsigned comment added by Adresia (talk • contribs)

Classification Logic

I'm quite curious: if one has to strictly apply the paraphyletic rule to name groups, there would logically be but one group, that is the group of the first species originated on Earth: such a group, containing the single species from which all others have originated, must contain all such species. So where is the limit really put? It's not really discussed in the article... Gbnogkfs 25 May 2006, 21:34 (UTC)

- Could you be a little bit more specific? What is the paraphyletic rule? I know but one: do not include groups proven to be paraphyletic in the classification. Alexei Kouprianov 10:36, 26 May 2006 (UTC)

- You say it's better not to include paraphyletic groups in classification. The problem is that you can't apply this rule to every group, except if you want to create only one group, which is of course against the scope of a classification in the first place.

- To make an example: let's consider the Mammal and Reptile classes. Let's consider the most recent ancestor to all mammal and reptiles: in which class would you include it? If you put it in the Mammal class, then the mammal class is paraphyletic; if you put it in the Reptile class, then the reptile class is paraphyletic; if you put it in a third class, then that class is paraphyletic.

- The result is that if you want to create only non-paraphyletic groups, you are forced to put mammals, reptiles and their common ancestor into the same class.

- Eventually, repeating this process, all the living beings have to be put in the same class.

- There is common agreement even among anti-paraphyleticists on the existance of more than one class: where do you put a limit in the refusal of paraphyletic groups? Gbnogkfs 26 May 2006, 22:18 (UTC)

- You say it's better not to include paraphyletic groups in classification. The problem is that you can't apply this rule to every group, except if you want to create only one group, which is of course against the scope of a classification in the first place.

- No, you've got it all wrong. Just as the authors of the Wiki-article. The taxa do not include ancestors. Even the monophyletic ones. They include all (in case they are monophyletic) or some (in case they are non-monophyletic, i.e. para- and polyphyletic) terminal taxa (indivisible units of the analysis) believed to be descendants of the hypothetical most recent common ancestor. This comes from a logical premise that only sister-group relationships (and not the ancestor-descendant relationships) can be proven. Note, please, that I am just repeating an argument from the thirty-year old debates. It is all in the 1970--1980s. No matter for a discussion on this point any longer. Alexei Kouprianov 22:25, 26 May 2006 (UTC)

- I can't really get the whole of your answer, but then if the article is wrong, why doesn't anybody amend it? Gbnogkfs 26 May 2006, 23:33 (UTC)

- Well, I just did. I am sorry I was too technical (I was trained as a taxonomist). I hope that my reformulation of the article makes this less esoteric. Alexei Kouprianov 10:44, 27 May 2006 (UTC)

- So taxa are used only for "clades", with the exclusion of common ancestors: that is, for exemple, that the most common ancestor of Mammalia and Reptilia (and all of the ancestors of this last, in fact) is not included in any class (while being, for exemple, a member of the chordates). That's interesting: it was not clear at all! Gbnogkfs 27 may 2006, 12:43 (UTC)

- That's even more interesting. None of the still existing or fossil species could be unambiguously identified in principle as the most recent common ancestor of mammals, reptiles, mammals+reptiles, as well as of any other group. Hence, there is no real problem of classifying the ancestor. The real ancestor when discovered could pose a major problem, but no one is able to prove that this or that particular fossil really is the ancestor. The logically correct way to deal with fossils is to regard them as sisters (not mothers) of other fossil or recent groups. Alexei Kouprianov 13:57, 27 May 2006 (UTC)

- Indeed: a very sperimental approach. Thanks for the biology lessons :) Gbnogkfs 27 may 2006, 20:42 (UTC)

Definition re-broken

I happened upon this page again and saw that the definition had been re-broken since User:Saforrest's fix long ago (and other intervening fixes by other users). It said: "In phylogenetics, a group of organisms is said to be paraphyletic (Greek para = near and phyle = race) if the organisms have the same common ancestor, and the group does not contain all the descendants of this ancestor." I changed it to: "In phylogenetics, a group of organisms is said to be paraphyletic (Greek para = near and phyle = race) if the group contains its most recent common ancestor, but does not contain all the descendants of that ancestor." The definition was most recently broken by User:Pgan002. Please take care when rewording the definition. Roughly, all organisms on Earth have a common ancestor, and no non-trivial group of organisms contains all of the descendants of this ancestor. I also fixed the reference to Polyphyly. A5 16:17, 19 August 2006 (UTC)

Logical Inconsistencies

It was shown, however, that the inclusion of ancestors in the classification leads to unavoidable logical inconsistencies

Alexei, you would have to concede that the above statement is a matter of debate even today. I think the article should be edited to highlight some of the aspects of the differing approaches. Ordinary Person 13:13, 30 November 2006 (UTC)

- Well, I said everything I could in my posts from May 27. If one can prove that exactly this or that fossil bone is the actual ancestor of some recent group it's fine with me. I only doubt it is in principle possible. As soon as we include ancestors in the scheme, some taxa turn to be inherently paraphyletic. If the whole scheme was invented to avoid paraphyly, why let it back in? Alexei Kouprianov 14:14, 30 November 2006 (UTC)

That's a reasonable point. I wonder if some of this discussion can be worked into the article without dewikifying it. Ordinary Person 15:02, 30 November 2006 (UTC)

- Well, it was. The problem is that the definition in the very first paragraph of the article is not under my full control. I am mostly active in Russian Wiki and I come here from time to time just to make few corrections here and there. Meanwhile someone usually replaces a more theoretically rigorous but somewhat obscure definition with something more agreeable from the common sense perspective. The situation is getting more complicated because an average zoologist or botanist usualy does not pay attention to such subtlities, and, especially in the textbooks, one may find rather commonsensical definitions for mono-, poly-, and paraphyly, which are a bit far from the rigorous logic of original theories back in the 1980s, when the cladistic swords weren't yet rusty being stained with blood of the pheneticists and evolutionary taxonomists... I'll try to come back in a couple of days to try and reformulate the definition agaun but I can not guarantee that it will stay for ever. (Note: I am not complaining! It is just the way the things are...) Alexei Kouprianov 18:15, 30 November 2006 (UTC)

"Paraphyletic to"

We should define the common usage "paraphyletic to", as in "reptiles are paraphyletic to birds". It is arguably clearer (especially for a general audience) to say "reptiles are paraphyletic, because they exclude birds" which is almost as concise, but the "paraphyletic to" wording is pretty common and baffling if you don't know the shorthand. The only thing holding me back is that the dictionaries and glossaries I consulted only defined paraphyletic, not the usage with "to". So I don't have a source. Kingdon (talk) 19:50, 14 March 2008 (UTC)

Paraphyly, a concept not that difficult

The concept of paraphyly and paraphyletic taxa is realy quite simple. Best to start off putting cladobabble aside, to borrow Alan Kashlov's term. Cladistics may give a good picture of evolutionary progression and continuum, but it does not ordinarily give the best picure of how small groups fit within larger groups, such as how genera fit into families and families into orders.

A paraphyletic group or taxon is simply one that does not include all its descendants, as generally stated. Examples of paraphyleitc taxa are the Nautiloidea which do not include the Ammonoidea and Coleoidea to which they gave rise; Synapsid Pelycosuaria which does not include descentant mammalia, and Dinosauria in the normal sense that excludes the derived birds (Aves)

All taxa to be valid must be monophyletic, whether one is talking from a taxonomic or cladistic perspective. In other words it must have a single common ancestor, at least generically. All valid paraphyletic taxa are also monophyletic. The terms are not muturally exclusive. One, monophyly referes to ancestory, the other, paraphyly refers to partial inclusion. I suppose a group that included all the descendants from the most recent common ancestor would be holophyletic. Mammals and birds are holophyletic because there are no exluded descendants, none having yet evolved.

Polyphyletic taxa are another matter, in some ways the opposite of monophyletic. A polyphyletic taxon is one with more than one most recent common ancestor, united by some convergent feature. The bird-mammal example is a fair one. Although both are warm blooded, one, birds, has its orgin in the dinosaurs, the other, mammals in the cynodonts. A better example is the Nautilida and Ammonoidea, both coiled ectocochliate cephalopods. A single taxon lumping the Nautilida and Ammonoidea exclusively would be polyphyletic, and invalidsince the Nautilida are derived from the Oncocerida and the Ammondea come from the Orthocerida. The Oncoceroda and Orthocerida are only remotely related nautiloid cephalopods just as birds and mammals are remotely related amniote tetrapods. Polyphyletic taxa, which are invalid, are the result of convergence that results in the appearance of being closely related.

Paraphyly is an important principle in taxonomy. It keeps taxa from becoming overly diffuse to the point of having little meaning. It allows derived taxa to be asigned rank equal to that of the ancestral taxon as in Class Aves being equal to Class Dinosauria or Class Ammoidea being equal to Class Nautiloidea. Otherwise there'd be a case of diminishing returns. Paraphyly also keeps taxa in conversationally reasonable units. When we speak of dinosaurs we shouldn't have to add, non-avian. They are after all, aren't they.

John McDonnell —Preceding unsigned comment added by J.H.McDonnell (talk • contribs) 01:28, 25 July 2008 (UTC)

The problem with this incomplete definition of paraphyly

The problem with the definition of paraphyly as stated in this article is that it is incomplete. Paraphyly also includes the groups of presently existing biological species of monophyletic groups (that is, holophyletic groups and paraphyletic groups as defined in this article) of biological species (for example humans and chimps or chimps and gorillas). Groups including ancestors are ambiguous per definition, since thing and kind (i.e., thing and its properties) are not synonymous (or equal). Things do have properties, but properties do not have things. It means that there are two kinds of monophyletic groups: holo- and paraphyletic groups. Cladistics does not understand this fact, whereas the Linnean classification system incorporates it. Mats, presently at 83.254.23.241 (talk) 09:02, 19 January 2009 (UTC)

Shouldn't Agnatha be polyphyletic?

"Agnatha, jawless fish. This group contains two significant animal groups, hagfish and lampreys. Their nearest common ancestor is the ancestor of all vertebrates, so Agnatha is paraphyletic."

compare to:

"A group that does not contain the most recent common ancestor of its members is said to be polyphyletic" and "group of organisms is said to be paraphyletic if the group contains its most recent common ancestor but does not contain all the descendants of that ancestor"

Unless hagfish or lampreys include the ancestor to all vertibrates then it can't be a paraphyletic group. If the common ancestor to all vertibrates is included in either hagfish or lampreys then the article should make this clear.

I'm not going to alter the article myself as this isn't my field and I don't know which case is the correct one.

-- Michael Mortimore —Preceding unsigned comment added by 82.32.248.147 (talk) 08:11, 27 March 2009 (UTC)

Eubacteria?

The article at Neomura shows that, according to Thomas Cavalier-Smith, the Eubacteria are paraphyletic (for example, bacteria such as Actinobacteria are more closely related to Neomura than they are to, say, Cyanobacteria). Should this be included? It seems significant 24.34.94.195 (talk) 01:53, 8 September 2009 (UTC)

Originator of term?

Wasn't the term introduced by P.D. Ashlock, entomologist at University of Kansas?

72.49.254.33 (talk) 12:00, 11 October 2009 (UTC)

- It's possible. The earliest use of paraphyletic given by the OED is the appearance in the translation of Willi Hennig's 1965 paper in Annual Review of Entomology. Do you have evidence of an earlier use by Ashlock? --Danger (talk) 18:13, 11 October 2009 (UTC)

Gobbledeygook

"Before that period the distinction between mono- and polyphyletic groups was based on the inclusion or exclusion of the most recent common ancestor. It was shown, however, that the inclusion of ancestors in the classification leads to unavoidable logical inconsistencies, and, in some schools of taxonomy, the phylogenetic pattern is described exclusively in terms of nested patterns of the sister group relationships between the known representatives of taxa without referring to the ancestor-descendant relationships."

What logical inconsistencies? What schools of taxonomy? Do you mean most recent of last common ancestor? Just what do you mean? If you follow sister group it takes you to cladistics and there sister group is defined as part of a clade. Why is known emphasized? Really, this unreferenced passage says nothing comprehensible at all, and it would not help to throw in a reference, much less a whole book without page numbers, such as Simpson. Reference what? At this point I have to say, either do it right or do not meddle.Dave (talk) 15:07, 24 January 2010 (UTC)

Insertion of linguistics by tim

Hello Tim. I got on this article from linguistics myself, as I saw linguistics terms being tossed casually around there. Historical linguistics is using the family tree model, which naturally developed into phylogeny. However, biological classification is in a state of flux so we want to be careful how far to extend the analogy. But I found that the biological articles couldn't even be understood. As to your changes, they are not the best changes to make. Yes, something on linguistics should be in there. You are getting a bit ahead of me. I was going to do it, but first things first. No, it does not belong at the top of the page. This is primarily a biological not a linguistics article. Moreover, you're not saying anything about it. We need to define what it means when paraphyly is applied to linguistics. Merely quoting another WP article I believe is against the policy. WP is NOT a source for WP articles unless they are about WP. Now, we are not lacking in linguistics in these cladistics articles. Check Cladistics. In each case the linguistics is mentioned under non-biological uses at the bottom. So, I'm moving you to the bottom. Moreover, since you have said nothing, there is nothing to move. So, I;m taking out your quote of the WP article. We need a place holder, however, so I'm putting in a single introductory statement. Anyone including you can expand it, but I have to warn you it is a steep subject so if you are not prepared perhaps you should wait for someone else. For myself I thought, first let's get the biology clear and then we can take on the linguistics. Finally, you took the picture from the top. Unless you have a better biological picture I am putting it back on top. Thanks for your interest in the topic.Dave (talk) 13:05, 25 January 2010 (UTC)

- I added a reference to the linguistics section. I will say this, though, in my personal experience, most historical linguists would not use the term. Really, only the very small subset who also use computational phylogenetic methods would ever use the term. --Limetom 03:05, 18 April 2010 (UTC)

Logical inconsistency

The version as of 05:08, 17 October 2010 contains an important inconsistency. The first paragraph said:

- "A group of taxa is said to be paraphyletic if the group contains its last common ancestor but does not contain all the descendants of that ancestor."

Later the definition was given as:

- "A paraphyletic group is a monophyletic group from which one or more of the clades is excluded to form a separate group (as in the paradigmatic example of reptiles and birds, shown in the picture)."

The first definition is not correct; if we take a monophyletic group of classified entities and randomly remove some of them we don't necessarily get a paraphyletic group. The second definition is correct for current usage: the missing members must form monophyletic groups -- actually I think generally the term is only used when one such group is missing, i.e. a 'crown and stem' classification. I have edited the article to ensure consistency with the later definition. Peter coxhead (talk) 10:45, 5 December 2010 (UTC)

- Reptilia has two groups missing (Aves and Mammalia). Your changed wording still covers it, though.--Curtis Clark (talk) 17:13, 5 December 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks, good example (depending on how you define the full Reptilia clade). I think that paraphyly is usually a term employed with one missing monophyletic group, but clearly there can be more than one (i.e. 'stem and crowns' rather than 'stem and crown'). My definition in the opening sentence was still not quite right though: it has to be "if the group consists of all the descendants of a possibly hypothetical closest common ancestor minus ...". I think that the following are the completely correct definitions of the three kinds of classification as currently used:

- Monophyly = all descendants of the closest common ancestor of the group's members (plus the closest common ancestor if ancestors are being included in the classification).

- Paraphyly = a monophyly minus one or more sub-monophylies

- Polyphyly = everything else.

- In particular I can't find a neat form of words to define polyphyly other than as "what is left". The definitions I've seen are usually also applicable to paraphylies. Is there one? Peter coxhead (talk) 15:15, 6 December 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks, good example (depending on how you define the full Reptilia clade). I think that paraphyly is usually a term employed with one missing monophyletic group, but clearly there can be more than one (i.e. 'stem and crowns' rather than 'stem and crown'). My definition in the opening sentence was still not quite right though: it has to be "if the group consists of all the descendants of a possibly hypothetical closest common ancestor minus ...". I think that the following are the completely correct definitions of the three kinds of classification as currently used:

- Reptilia has two groups missing (Aves and Mammalia). Your changed wording still covers it, though.--Curtis Clark (talk) 17:13, 5 December 2010 (UTC)

The sentence "Reptiles would be monophyletic if they were defined to include Mammalia and Aves" is confusing in light of the accompanying picture. It doesn't show Mammalia as a descendant of the node Reptilia. According to the picture, Amniota would have to be thrown in as well, so I am adding a brief explanation. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 24.141.106.132 (talk) 12:46, 6 October 2011 (UTC)

Definition of paraphyly, again

The current definition of paraphyly in the article is a good one, better than most that one can find.

- . . . .a taxon is said to be paraphyletic if the group consists of all the descendants of some ancestor minus one or more monophyletic groups of descendants.

It is not quite good enough, though. Consider the "ur-therian", the last common ancestor of humans and kangaroos. By the definition above, the group consisting of all the descendants of the ur-therian minus the Metatheria, which is a monophyletic group of of descendants, would be a paraphyletic group. It isn't, though; the group picked out by this definition is the Eutheria.

One way of meeting this objection would be to add, as another condition that a group must meet to be paraphyletic, that it not be monophyletic. Is there a way of fixing the definition up that is less ad hoc?

Peter M. Brown (talk) 23:11, 18 June 2012 (UTC)

- It's probably in the history, but what are the issues with "a common ancestor and some, but not all, of its descendents"?--Curtis Clark (talk) 04:59, 19 June 2012 (UTC)

- Exclude the common ancestor from the group for the present, and consider a group defined as "some but not all of the descendants of a common ancestor". Clearly a group defined in this way can be what is usually called polyphyletic: birds + mammals are some but not all descendants of a common amniote ancestor. So the question is whether adding in the common ancestor makes the group paraphyletic rather than polyphyletic. It doesn't seem to me that it does: a group defined as a combination of (some amniote ancestors prior to the mammal-reptile split) + (mammals) + (birds) wouldn't, I think, be called "paraphyletic". Of course, no-one would form such a group; I suspect that "sensible" groups (e.g. those with shared apomorphies) meeting your definition will be paraphyletic, but at least in principle they need not be. Peter coxhead (talk) 13:15, 19 June 2012 (UTC)

- Whether it's sensible or not, a group of this sort is given as an example in the Not Paraphyly section: the quadrupedal diapsids. The common ancestor, a close relative of Petrolacosaurus or perhaps a captorhinid, was surely quadrupedal, so the group does consist of "a common ancestor and some, but not all, of its descendents". The group is not paraphyletic, though. The excluded group—the bipedal diapsids—is neither a clade nor the union of two or more clades, since bipedal dinosaurs were ancestral to quadrupedal ones. Peter M. Brown (talk) 01:32, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- Good example. So it's clear that the definition of paraphyly must say that the excluded group(s) are clade(s) and the definition which Curtis Clark quoted (which is in the literature) is simply not correct. I think we did establish this before! Peter coxhead (talk) 09:50, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- Okay, if I'm understanding you correctly, the equivalent would be to make a group consisting of the limbless descendents of the first (limbless) vertebrate, so that it would include lampreys and snakes, but not lizards. If I'm on the right track, I definitely see your point, but you've opened a small can of Vermes. The current Wikipedia definition of polyphyletic (which is consistent with definitions in the literature) is "A polyphyletic (Greek for 'of many races') group is one whose members' last common ancestor is not a member of the group." By your definition of paraphyly, the group of limbless descendents of the first vertebrate would not be paraphyletic, but by the definition in polyphyletic, neither would it be polyphyletic. In this article, it says that "A taxon that is not paraphyletic or monophyletic is polyphyletic," which makes this article internally consistent but at odds with the other article.

- I'm not trying to be contentious here, but I call original research. Your definition may very well be better (although I'm not convinced of that), but I don't see any clear literature references for it, and your statement above, "The current definition of paraphyly in the article is a good one, better than most that one can find," also hints at original research. Please explain to me how I'm wrong about this.--Curtis Clark (talk) 14:57, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- It occurs to me that another way to say this is that a monophyletic group, upon exclusion of an included monophyletic group, becomes paraphyletic, but, on exclusion of an included paraphyletic group, it becomes polyphyletic. Is that consistent with your definition?--Curtis Clark (talk) 16:01, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- We all would agree on the first part. Peter coxhead and I disagree about polyphyly and I do not anticipate resolution; see #Reversions and definition of polyphyly. As regards OR, you may be quite right; I would welcome Peter c.'s take on the matter. Peter M. Brown (talk) 17:32, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- In response to Curtis Clark, no, it's not OR, although it is careful scholarship. What I mean is that the correct definitions are in the literature, together with analyses of why other definitions are wrong. This was all discussed and sorted out in the 1970s and 1980s by people like Ashlock, Bock, Farris and Oosterboek. Oosterboek (1987) is the first fully correct set of definitions that I've found: Oosterbroek, Pjotr (1987), "More Appropriate Definitions of Paraphyly and Polyphyly, with a Comment on the Farris 1974 Model", Systematic Biology, 36 (2): 103–108, doi:10.2307/2413263. Oosterboek's definition of paraphyly is: "A group of taxa is paraphyletic if their most recent common ancestor has given rise to one or more excluded taxa or monophyletic groups of excluded taxa of which the sister group(s) is (are) completely included in the group." As far as I can tell this is the only fully correct definition, but I've never seen it quoted in recent literature. The last part ("of which the sister group(s) ...") is omitted, but without it, there are groups which don't correspond to what most biologists seem to mean by "paraphyletic" but which aren't excluded by the shorter definition. Speaking as a computer scientist, I would say that unfortunately biologists don't seem very interested in precise definitions, and this early work seems not to have been properly taken on board by later workers.

- Another problem has been pointed out by Podani (2010), namely that there is a difference between definitions based on "cladograms" (in which the interior nodes never represent taxa used in the analysis; they merely define the branching order of the evolution of the leaves) and those based on "phylograms" or "phylogenetic trees" (in which the interior nodes are real taxa). Podani tried to introduce a distinction between e.g. "paraclady" and "paraphyly" based on these two kinds of tree. This didn't catch on, so that "paraphyly" is used to include both his "paraclady" and his "paraphyly"; however they are slightly different and some definitions only cover one of them. See Podani, J. (2010), "Taxonomy in Evolutionary Perspective : An essay on the relationships between taxonomy and evolutionary theory", Synbiologia Hungarica, 6: 1–42.

- Now to some extent this can be regarded as nit-picking, because in practice most paraphyletic groups which are still used are formed by excluding one clade, and all(?) the definitions agree under those circumstances. The subtle differences between the definitions arise when more than one clade is excluded.

- I haven't yet been able to work out whether "a monophyletic group .. on exclusion of an included paraphyletic group .. becomes polyphyletic" is right or not! Peter coxhead (talk) 19:17, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

Now sorted out the query by Curtis Clark. Consider this cladogram:

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The group consisting of A+B+C is (singly) paraphyletic; the clade D+E is omitted from the clade A+B+C+D+E. Omitting the paraphyletic group leaves a monophyletic group. So the possible definition is not correct.

- Sorry to post in the middle of your post, but there seems to be something missing here. Your first sentence says you are omitting a monophyletic group, and the remaining group is paraphyletic. I concur. Your second sentence seems a non sequitur; what paraphyletic group are you omitting?--Curtis Clark (talk) 20:45, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

The interesting case is the group consisting of A+B+E (and their hypothetical common ancestor). Is this paraphyletic or polyphyletic? Since C and D are clades (whether they are single taxa or groups of taxa), the "short" definition says that A+B+E is (doubly) paraphyletic: two clades have been removed from a clade. Oosterboek's definition says that A+B+E is polyphyletic because the sister group of the excluded C (i.e. D+E) is not completely included. This fits the mammals+birds case and makes sure that such a group is polyphyletic, whereas without the sister group requirement, mammals+birds appears to be paraphyletic if ancestral taxa are included in the group and only complete clades like Testudines, Lepidosauria and Crocodylia are excluded. Peter coxhead (talk) 19:39, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- Some famous cladist or another back in the 1980s pointed out that a paraphyletic group could be distinguished from a polyphyletic group only by considering the explicit inclusion or exclusion of common ancestors (this was used as one of several justifications for not using paraphyletic groups in classification). It seems like what you are saying is that we can have a definition that doesn't specify anything about ancestors.

- Not me, but Oosterboek and Podani (to mention just two). Peter coxhead (talk) 21:26, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- The point I was making above is that, in the cladogram below, the exclusion of D+E+F would leave the remainder paraphyletic by either definition, but the exclusion of the paraphyletic group D+E (itself paraphyletic by the exclusion of F) would leave A+B+C polyphyletic by this article's definition (again if I'm understanding correctly).

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

- If you mean A+B+C+F (which is what you get if D+E is excluded), then by Oosterboek's definition this is polyphyletic (because the sister group of D, which is excluded, is not completely included).

- "It seems like what you are saying is that we can have a definition that doesn't specify anything about ancestors" – yes, read Podani. Definitions based on cladograms (as produced by all current programs used in molecular phylogenetics) classify groups of leaf nodes based on the geometry of the tree; actual ancestors are irrelevant. But there are also definitions based on "phylograms" and definitions based on characters. As with definitions of species, biologists seem happy to use the concept of "paraphyly" without worrying too much about the precise definition they are using. But this does make it difficult to write an article! Peter coxhead (talk) 21:26, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- I guess we have to go with Oosterbroek, though the sister-group condition is news to me. How about the following?

- A group is called paraphyletic if it consists of all members of the more inclusive monophyletic group descended from its last common ancestor except those in some monophyletic subgroup. One example is the mammal-like reptiles, consisting of all synapsids except the mammals. Another is the non-avian sauropsids, the sauropsids that are not birds. It is important to these examples that synapsids, mammals, sauropsids, and birds are all monophyletic groups.

- A group may consist of all members of the monophyletic group originating with its last common ancestor with the exception of those in two or more monophyletic subgroups. A group of this sort is called paraphyletic when it consists (recursively) of a paraphyletic subgroup together with one that is either paraphyletic or monophyletic. The reptiles in the traditional sense, the amniotes minus the mammals and the birds, consists of the mammal-like reptiles together with the non-avian sauropsids, both of which are paraphyletic, so the reptiles are a paraphyletic group.

- This formulation does meet my original objection, since no metatherian is descended from the last common ancestor of the eutherians.

- The sister-group condition of Oosterboek is important in the several times paraphyletic case. I can't quite work out whether your second definition above complies or not. The key point is that in a complete tree of this shape ("ladder-like") where A–D are clades:

|

A | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

- it's not possible to exclude two separate clades leaving a paraphyletic group. Thus you can't exclude B and C to form a paraphyletic group A+D, for example, since once B is excluded its entire sister group must be included. This prevents ever being able to make a paraphyletic group equivalent to mammals+birds. To make a paraphyletic group by excluding two taxa/clades, they have to be in "separate lines". Thus in this tree

| |||||||

| |||||||

- the group A+D formed by excluding B and C is paraphyletic according to Oosterboek. This makes sense in terms of characters: in this tree it's plausible that the shared characters of A and D not present in B and C have a common origin.

- So does your second definition fit these cases? And other cases where the sister group condition applies? Peter coxhead (talk) 19:00, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

Back to your original point

This never got responded to; we rather drifted into more complex matters. I think it is implicit in the definition of a paraphyly that it's not a monophyly, and you can't avoid this. But then you'd expect me to say this because I think the decision process is:

- Is it a monophyly?

- If no, is it a paraphyly?

- If no, it must be a polyphyly.

- Whereas the discussion below suggests to me that you think it's possible for a group to be none of the three. Peter coxhead (talk) 19:00, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

Why have three articles?

Please see Talk:Monophyly#Why_have_three_articles where I have asked why there should be separate articles on monophyly, paraphyly and polyphyly. Please leave comments there. Peter coxhead (talk) 15:57, 6 December 2010 (UTC)

Vertebrates derived from invertebrates

The article was saying : "Invertebrates are defined as all animals other than vertebrates, although vertebrates are derived from this larger group". I removed "larger", because it implies that vertebrates are a subset of invertebrates.Stefan Udrea (talk) 10:37, 15 January 2011 (UTC) I mean, I can buy that birds are some kind of reptiles, but I can't buy that vertebrates are invertebrates, it's a glaring oxymoron.Stefan Udrea (talk) 11:07, 15 January 2011 (UTC)

Reversions and definition of polyphyly

Recent reversions, most of which I have no objection to, returned to this definition of polyphyly: "A group whose members' last common ancestor is not a member of the group is said to be polyphyletic". Well, this is indeed said by some sources, but presented as a "stand alone truth" I don't think it's correct. Polyphyletic groups typically get created for two reasons: they are what is left over in a large group when subgroups with distinctive features are removed, i.e. they are defined by shared symplesiomorphies (for botanists, consider the old Liliaceae), or they are created by putting together groups which have independently evolved a defining apomorphy. The latter is excluded by the definition; the former is often not, since the last common ancestor may well be a member of the group based on the symplesiomorphies. Suppose I created a taxon for all flightless Paraves; this would clearly be polyphyletic, but the hypothetical ancestor would be a member of the group.

So I have reverted to the earlier negative definition: what's left when the other two are removed. Peter coxhead (talk) 09:58, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Hennig defined polyphyletic groups has those characterized by the possession of convergent characters. That really does seem to be the meaning used today. To demonstrate that a group is polyphyletic, one shows that some of the characters that unite the group arose independently in two or more subgroups. That reflects the etymology of "polypheletic": Greek πολύς [polys] "multiply" + φυλετικός [phyletikos] "tribal". So interpreted, though, a group that is neither monophyletic nor paraphyletic may yet fail to be polyphyletic.

- In nearly all eukaryotic cells, most of the heterochromatin is situated at the nuclear periphery while euchromatin resides toward the nuclear interior, a structure that facilitates transcriptional regulation. As Solvei et al. (2009) have noted, however, the pattern is reversed in the retinal rod cells of nocturnal therians: heterochromatin is at the center and euchromatin further out. As they interpret the matter, ancestral therians were nocturnal and the reversed pattern evolved to facilitate passage of light to their photosensitive pigments. When some of their descendants became diurnal, the normal pattern reasserted itself. This kind of evolutionary flexibility did not arise among sauropsids; the retinal cells of nocturnal birds have the normal pattern.

- Are the tetrapods with normal rods a polyphyletic group? By Hennig's definition, they are not. The normal pattern, which has been standard for two billion years and is characteristic of nonretinal cells in all tetrapods, is expressed homologously in the retinas of diurnal mammals. It is not a convergent character. However, the group is neither paraphyletic nor monophyletic, since (on the view of Solvei et al.) diurnal therians have had nocturnal ancestors, with the reversed pattern, among the tetrapods.

- It seems to me that by Hennig's definition tetrapods with normal rods are a polyphyletic group. Normal rods evolved in tetrapods in two ways: firstly, as a common symplesiomorphy for those groups without a nocturnal ancestor; secondly, by reversal of an apomorphy of nocturnal therians creating a new apomorphy in diurnal mammals. Convergence doesn't have to mean the parallel evolution of new characters. The continuation of an ancestral character and the evolution of it again in a group after it disappeared are also convergent. For example, a streamlined shape is convergent in dolphins, ichthyosaurs and sharks. It's irrelevant that sharks continued an ancestral character whereas ichthyosaurs and dolphins re-acquired it. (A Google search for "dolphin shark convergent evolution" will show that the term is widely used in this way.) Peter coxhead (talk) 22:10, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- I do think that Hennig's definition is the one used in practice and that, therefore, the negative definition of polyphyly should not be promoted.

- If it can be shown from reliable sources that Hennig's definition is still the one used most, then of course the article should say this. It's not my impression, but I guess it depends on what research you most read. I mainly read molecular phylogenetic stuff, where the question of what were the characteristics of the hypothetical ancestors hardly arises, and monophyly/paraphyly/polyphyly is defined (to the extent that these terms are used) from the geometry of the trees involved. In this approach, the three kinds of "phyly" are exhaustive. It is possible to give a non-negative tree-based definition; Oosterbroek did so in 1987: "A group of taxa is polyphyletic if their most recent common ancestor has given rise to excluded taxa of which at least one of the sister groups is only partly included in the group." However, this not easy to understand, even when you've drawn the tree!

- I'm not sure that even Hennig's definitions of the three kinds of "phyly" were meant not to be fully inclusive; do you have a source that says this?

- Actually, I don't think the definition of polyphyly matters that much. Monophyly is important, because everyone agrees that monophyletic taxa are "good". Paraphyly is important, because a not insignificant group of biologists still defend paraphyletic taxa (perhaps only singly paraphyletic taxa). But no-one (to my knowledge) defends polyphyletic taxa, regardless of the definition. Peter coxhead (talk) 21:37, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

So what's the point?

The part I'm still unclear about is why the different definitions? What is the perceived value of one over another? Did the authors of the definitions just come up with them ad hoc, as a way of grappling with the concept, or is one definition promulgated as being superior to another? (I know I could look them up, and I will if I have to, but one or both of you may already know.) This is important for the article: if there are contrasting non-fringe definitions, the article should mention them all, and it would be useful to explain why there's more than one.--Curtis Clark (talk) 22:20, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- I think there are several reasons for the different definitions.

- The simplest is that biologists haven't been interested in more than singly paraphyletic groups. Consider the arguments about Portulacaceae s.l. There was some support for taking out Cactaceae because of its clear apomorphisms leaving a paraphyletic Portulacaceae s.l. But no-one seems ever to argue for taking out, say, Cactaceae and Didiereaceae, leaving a paraphyletic Portulacaceae s.l. Once a couple of groups need splitting off, then it seems that a full breakdown is preferred. So in reality, as I noted above, the definition of paraphyly when more than one clade is removed from a clade is only of interest to theoretically minded people and "loose" definitions often serve perfectly well (e.g. ignoring Oosterboek's sister group requirement).

- Biologists know what they mean but aren't too bothered about precise definitions; they aren't used to being as formal in defining concepts as are mathematicians and physical scientists. As an example, the definition in the Glossary of APweb is "paraphyletic: a taxon made up of members which, given a particular phylogenetic tree and classification based on it, include only but not all the descendents [of] a common ancestor, likely to be a grade". However, given the first tree in the Paraphyly article, a taxon made up of mammals+birds includes only but not all the descendants of a common amniote ancestor and so is paraphyletic by this definition. Stevens, or whoever wrote the definition for him, knows perfectly well what a paraphyletic group is (there used to be a diagram on the site, which I can't find now, similar to the one we have in the article), but the definition is just wrong.

- The other reason is the diversification of the techniques now included under the broad heading of cladistics/phylogenetics. Definitions from the Hennig era of explicit tree building based on selected morphological characters have been imported into methods which use computational tree building based on genes or proteins. Using the terminology of the PhyloCode, computational trees are really only suited to node-based definitions (rather than branch-based or apomorphy-based): the branches don't contain real organisms and the molecular apomorphies are implicit (and often not actually studied). Although the PhyloCode authors well understand the need for slightly different definitions, it's not clear to me that most users of computational phylogenetic packages do. Again it seems to me that in specific cases everyone is clear about what is paraphyletic and what isn't, but this is based on understanding a tree, not on precise definitions.

- In summary, I think that where these concepts (monophyly, paraphyly, polyphyly) are used, there's no confusion: I've never seen a dispute in the literature over whether given a particular tree shape a particular taxon is paraphyletic or polyphyletic. But when theoretically minded people (or teachers) try to give precise definitions, then there is confusion, and many of the definitions widespread in the literature have been shown elsewhere in the literature to be wrong.

- In terms of Wikipedia, the problem is not OR but perhaps SYNTH. Alternative definitions and corrections to common definitions can all be sourced, but I haven't found a source for the kind of discussion we are having here. Peter coxhead (talk) 08:54, 22 June 2012 (UTC)

- Okay, here goes:

- Reptilia is a classic doubly paraphyletic group, and in fact was one of the first groups used in teaching to illustrate paraphyly, because most students had at least a general familiarity with "reptiles", mammals, and birds. (And of course it is still used as an example in the article.)

- Traditional definitions of paraphyly and polyphyly always included reference to whether the common ancestor was included or excluded. It's hard to imagine a character set which would unite mammals and birds and also include the first amniote. Where APWeb falls down is not making explicit that a paraphyletic group includes the ancestor. Certainly that is implicit in the general use of the term "evolutionary grade".

- I'm not sure what you mean by "the branches don't contain real organisms". I assume you mean other than termini, in which case this is true for any tree (other than perhaps species-level trees showing peripatric speciation). I agree that molecular trees are not easily apomorphy-based, but I'm not sure why that matters. And it should be noted that few investigators use molecular evidence to establish paraphyletic groups; rather they seek to avoid them.

- Okay, here goes:

- Admittedly I wasn't paying as much attention to the literature for the last eight years when I was in administration, but prior to that, there was a general sense that a paraphyletic group was an "impaired clade", that it was a clade with terminal taxa excluded, but with the hypothetical common ancestor included. That was a useful definition, and I still don't see any reason to abandon it, especially in favor of a definition that would call a group polyphyletic that explicitly includes the common ancestor of all its members.--Curtis Clark (talk) 15:32, 22 June 2012 (UTC)

- This is getting a bit long for a talk page, but it is relevant to the article, I think.

- Your comments above mix up definitions based purely on the geometry of the tree and definitions based on apomorphies. You wrote

Traditional definitions of paraphyly and polyphyly always included reference to whether the common ancestor was included or excluded. It's hard to imagine a character set which would unite mammals and birds and also include the first amniote.

But these two sentences make clear that whether the common ancestor is included or not is not sufficient; you are invoking characters to say that the first amniote, mammals and birds don't form a paraphyletic group. So your definition of a paraphyly isn't actuallya clade with terminal taxa excluded, but with the hypothetical common ancestor included

because this allows first amniote+mammals+birds. Your definition actually requires something extra (e.g. common derived characters). Peter coxhead (talk) 17:25, 23 June 2012 (UTC)

- It's relevant to the article because of NPOV.

- WRT your statement above, I'm not saying that at all. I assume you concur that trees in order to be useful must be evidence-based, and that an article about paraphyly of evidence-free trees wouldn't be useful. I mention character evidence as only an example; if you have different types of evidence that you'd bring to bear on that same issue, I'd be glad to discuss them. What I was saying is that mammals, birds, and their common ancestor do form a paraphyletic group, but that it's hard for me to imagine evidence (character or otherwise) that would support it. The definition that I presented is completely topological.--Curtis Clark (talk) 05:01, 24 June 2012 (UTC)

- Ah, right. So you are saying that the "simple definition" is correct in calling amniote ancestor+mammals+birds paraphyletic, it's just that no-one would propose such a group on character grounds. Can you source this? Not the "simple definition" (what I believe to be wrong definitions are easily sourced) but a statement that a group that would be non-paraphyletic using a fuller definition is paraphyletic? My reading of the literature is different. All the examples I find of groups called paraphyletic or polyphyletic are as I would expect them to be. It's just that the so-called definitions given are not complete (they give necessary but not sufficient conditions).

- At present the set of articles (monophyly, paraphyly, polyphyly) assume that there are different "modes" (e.g. different definitions of node-based, stem-based and apomorphy-based clades) but for each mode there is one "correct" definition: e.g. there is one correct node-based definition of a paraphyletic group. Whereas, if I understand you correctly, you are saying that we should describe different definitions (within a given mode) and explain that they classify groups differently. Can you source this? I.e. an acceptance of groups being classified differently by different definitions (within a mode)? Because all the sources I know that explain that different definitions lead to different decisions as to whether groups are monophyletic, paraphyletic or polyphyletic use this to argue that only one of the definitions is correct. Peter coxhead (talk) 07:35, 24 June 2012 (UTC)

- Can I source describing different definitions? WP:NPOV. But I'm pretty certain that's not what you're asking. And I don't see any apomorphy-based definitions, nor do I immediately see any stem-based definitions (although I could easily be wrong about the latter) in monophyly or this article, although cladistics discusses the three for defining clades. For my purposes, node-based and stem-based definitions of paraphyly should be functionally equivalent (the definition I support predates a general distinction between the two), and I can't immediately think of an apomorphy-based definition that doesn't also rely on tree topology.

- Let me lay out my logic chain, and you tell me which parts need to be sourced:

- A common definition of paraphyly is "a common ancestor and some, but not all, of its descendents" (or some variation thereof). I think you and I agree that this definition exists.

- That definition requires a consideration of whether the common ancestor is included or excluded. I hope you agree, and I hope you agree also that this isn't WP:SYNTH.

- By inspection, it cannot be determined whether any given group of terminal taxa is monophyletic, paraphyletic, or polyphyletic, in the absence of a tree. I hope you agree here as well.

- Because by this definition, a paraphyletic group must contain its common ancestor, and by the traditional definition of a polyphyletic group, it must exclude the common ancestor, the same group of terminal taxa could be paraphyletic or polyphyletic, depending on this inclusion or exclusion. I might be able to dig up a reference for this, it was in the 1980s, so a lot depends on whether it, or some reference citing it, is available in a searchable digital format (if not, it's easier to put a disputed tag on the article than spend hours in a library).

- None of this addresses whether all the other internal nodes leading to the terminal taxa must also be included for a group to be paraphyletic. I admit this is a shortcoming of the definition, although I think most supporters of the definition, on contemplation, would say that they do.

- Thus, mammals+birds is either polyphyletic or paraphyletic, depending on whether the basal node (and possibly intermediate nodes) is included or excluded. I hope you agree that if one accepts the steps leading up to this, this is a logial conclusion.

- It's finally clear to me that the definition in the article is consistent with the requirement that all internal nodes leading to the terminal taxa need to be included. I would give my students the example of the branch of a tree. One cut removes a clade, topologically speaking. If you make additional cuts removing branchlets from the cut branch, the remaining single structure is a paraphyletic tree, and all the removed pieces are clades.

- Am I being clear here? I keep feeling like we agree, underneath all this.--Curtis Clark (talk) 16:02, 24 June 2012 (UTC)

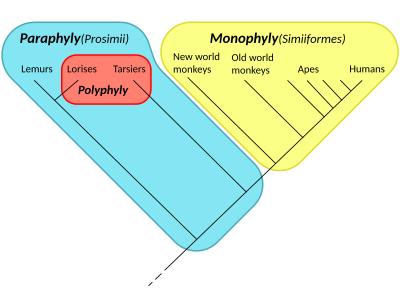

Primate cladogram and definition

I've been away from Wikipedia so I missed the addition of the new diagram using primates as the example. In terms of the definition given in the lead, why are (lorises+tarsiers) polyphyletic? They consist of a monophyletic group (primates) minus two monophyletic groups (simiiformes and lemurs). In this case asking whether the ancestors are included or not doesn't help, since it's plausible that all were nocturnal and lemurs and simiiformes represent parallel evolution of diurnal behaviour and characters. So by the definition, (lorises+tarsiers) form a (doubly) paraphyletic group. Indeed they form a classic doubly paraphyletic group: distinguished by the retention of a hypothetical ancestral condition which has been independently superseded in the two removed groups. Peter coxhead (talk) 07:53, 16 July 2012 (UTC)

- Petter Bøckman proposed essentially the new diagram here, four months ago. As there was no objection, I assumed that we had consensus and implemented it with minor tweaks. If it is unacceptable, we need something else. My objections to the prior diagram, File:Phylogenetic-Groups-Rev.svg, were (1) that Reptilia was a node, implying monophyly, though the text of the associated articles held that the group was paraphyletic, and (2) that it showed Testudines outside of Diapsida, violating neutrality.

- We could stick with the primates, taking the diurnal primates as the polyphyletic group, if somebody out there is competent to produce a diagram. (Petter is on an extended Wikibreak.) It would still be necessary to produce an apomorphy and a plesiomorphy for use in Cladistics#Terminology for characters. Surely there is a traditional synapomorphy singling out the Simiiformes? If so, its absence could be used as a plesiomorphy of the prosimians. Peter M. Brown (talk) 15:29, 16 July 2012 (UTC)

- If by "diurnal primates" you mean (simiiformes+lemurs), i.e. the inverse of (lorises+tarsiers), then using the "tree geometry" definition, this group is also paraphyletic: two monophyletic groups (lorises and tarsiers) have been removed from a monophyletic group (primates). In this case, modifying the "tree geometry" definition to require the LCA to be included suggests that the group is instead polyphyletic, since the LCA is not thought to be diurnal. However, it would be better to find an example which works under the widest possible range of definitions of paraphyly.

- An example of a group which is polyphyletic under all the "tight" definitions I know is (Old World monkeys+lemurs), i.e. "diurnal Old World primates". This meets even the very tight definition of Oosterbroek (1987).

- I can re-do the diagram, if there is consensus on the example. Peter coxhead (talk) 07:48, 17 July 2012 (UTC)

- I concur enthusiatically. Have you a primatological suggestion for Cladistics#Terminology for characters? Peter M. Brown (talk) 15:29, 17 July 2012 (UTC)

Proposed revision to the lead

I need to explain why I am reverting this recent good-faith change to the lead.

In the edit summary, the editor claims that "this article is about the biological meaning, and the introduction should reflect that rather than attempting to be a dictionary definition encompassing all meanings." A good dictionary definition, though, does not encompass meanings; a dictionary entry typically lists several meanings and provides a precise definition for each. The most prominent difference between the old text and the new is that the reference to paraphyly in linguistics has been omitted, in accordance with the editor's claim that the article is about the biological meaning.

To support this change, some argument is necessary to the effect that there is a specifically biological meaning; that paraphyly is not, univocally, an attribute both of groups of biological taxa and of language families. According to Wikipedia, there are five kinds of wine presses, but all five are wine presses in the same sense; similarly, the Paraphyly article has been assuming that there is a single sense in which both kinds of groups can be paraphyletic. The burden of proof, I submit, is on those who maintain that a term is ambiguous. Anyone who proposes that there are five senses of "wine press" needs to make a case for the ambiguity before editing that article.

In addition to dropping the reference to linguistics, the editor has made a number of stylistic changes. Some of these are constructive, like the use of paraphyly instead of paraphyletic in the first sentence. Others, though, I take issue with. The editor has

Changed from . . .if the group consists of all the descendants of the last common ancestor of the group's members. . . . to . . .applying to groups in which all members are descendants of a single most recent common ancestor. . . .

It was I who replaced [[most recent common ancestor]] with [[most recent common ancestor | last common ancestor]] sometime back. I am accepting the statement in the Most recent common ancestor article that "most recent common ancestor" is usually used to describe a common ancestor of individuals within a species while "last common ancestor" typically means a common ancestor between species. As the article does discuss both, a link to it is appropriate, but "last common ancestor" is best used in the Paraphyly article.

(Incidentally, this is an article where ambiguity is acknowleged and the different senses are intelligently discussed. Perhaps, even if "paraphyly" is ambiguous, both senses can be treated in the same article?)

Further, not every last common ancestor will do. As I have argued above, a definition that does not identify the group of which the LCA is being considered is inadequate. I have revised the lead to specify the LCA of the group's members; this meets the objection. This qualification should not be dropped.

Continuing, the editor has

Changed from . . .minus one or more monophyletic groups of descendants. . . . to . . .excluding one or more monophyletic subgroups of descendants, which are themselves groups only of descendants of a single most recent common ancestor. . . .

The clause "which are. . .ancestor" is redundant and clutters up the formulation; it has already been said that the group(s) in question are monophyletic.

Finally, the last sentence of the revised lead contains the archaic word "descendancy", which is not helpful.

Peter M. Brown (talk) 18:11, 16 July 2012 (UTC)

- Although the editor's changes were well-intentioned, I support the reversions noted above. Peter coxhead (talk) 08:03, 17 July 2012 (UTC)

Perhaps, even if "paraphyly" is ambiguous, both senses can be treated in the same article?

– actually, as I've argued above, I think there are more than two senses. Firstly there is a division between "tree geometry" definitions and "character" definitions. Then the "tree geometry" definitions vary in tightness: the widely quoted very loose definition says only that one or more clades are excluded. This is often tightened by requiring the LCA to be in the paraphyletic group. I think that only Oosterbroek's 1987 definition is watertight, but it has rarely if ever been used. I'm still not sure that I fully understand the relationships between all the different definitions in the literature, but at some point these do need discussing in the article to ensure coverage, balance and neutrality. Peter coxhead (talk) 08:03, 17 July 2012 (UTC)

Replace incomprehensible first sentence?

Without wanting to restart old controversies, the first sentence of the lead is much less helpful than the second; and unfortunately, it's the first one that pops up when a link to the article is moused over (if you have that feature switched on). Could we either cut the incomprehensible first sentence, move it after the second sentence, or rewrite it? Chiswick Chap (talk) 10:41, 25 October 2014 (UTC)

- For the record, the first sentence in question was Paraphyly is a characteristic of some groups of organisms and families of languages, where one separates from other groups at a common origin point. This bit of the sentence "where one separates from other groups at a common origin point" makes no sense to me. One what? One group? If so, this is wrong because paraphyly can involve the exclusion of more than one clade. What "common origin point"? It has to be the most recent common ancestor. I'm removing the entire first sentence. Peter coxhead (talk) 11:30, 26 October 2014 (UTC)

- Thanks. That's much clearer. Chiswick Chap (talk) 12:02, 26 October 2014 (UTC)

The much thrashed-out discussion of the definition of paraphyletic resulted in a introductory sentence that stated the idea simply and correctly but with a potentially confusing cognitive tension between excluding and an immediately preceding all. I tried to rectify this tension using the word some in the lede sentence and the figure.CharlesHBennett (talk) 14:10, 9 March 2022 (UTC)

Superclass

Pages such as Actinopterygii list a "superclass" under scientific classification with an asterisk that links to paraphyly, but superclass is mentioned nowhere in the article. — Reinyday, 22:59, 5 January 2016 (UTC)

- The asterisk is meant to indicate that the superclass Osteichthyes is paraphyletic, which is why the asterisk alone links to "Paraphyly". It's nothing to do with it being a superclass rather than any other rank. I think the use of an unexplained asterisk in this way is misleading. I also note that the article Osteichthyes doesn't have an asterisk in its taxobox. The situation is complicated by the fact that "Osteichthyes" is used in two senses:

- Traditionally, to mean all bony fishes – a paraphyletic group because tetrapods (Tetrapodomorpha) are excluded.

- Cladistically, to mean the entire clade including tetrapods; in this sense, mammals, for example, are included in Osteichthyes.

- I don't think an asterisk linked to "Paraphyly" is very helpful to readers. Peter coxhead (talk) 17:14, 6 January 2016 (UTC)

Uncited lists

I have restructured the best of the examples as text (per WP:LISTDD), and removed the many uncited examples (per WP:V and WP:RS). This is an article on a theoretical topic, not an opportunity for multiplying WP:OR, nor adding favourite examples ad infinitum. Obviously there are very many possible examples (thousands, certainly), but it is not this article's job to list them all, nor would that be possible even if it were not hopelessly indiscriminate. The purpose of examples is to illustrate principles, and the text and images already do that clearly and adequately. If there is an unusual instance cited in the literature, that might be added; long lists are unconstructive and inappropriate, even worse if largely uncited and repetitive of a carefully-edited text. Chiswick Chap (talk) 21:29, 1 May 2018 (UTC)

- The examples of paraphyletic groups given in the list are taxonomic terms that can be found in the biological literature. It is therefore appropriate for a reader to know their paraphyletic status, as well as the corresponding monophyletic groups. Of course, many of these examples have been provided without citation, but this can be improved. Moreover, in an encyclopedic perspective, it is informative to make available and to detail the paraphyly / monophyly information of numerous groups. -- Manudouz (talk) 08:26, 2 May 2018 (UTC)

- The status of "numerous groups" should be detailed at the articles about those groups. I entirely agree with Chiswick Chap: all that is needed here are some carefully chosen and well referenced examples. I suppose there could be a separate article "List of paraphyletic taxa" but sourcing would be an issue. Peter coxhead (talk) 08:35, 2 May 2018 (UTC)

- Well, the uncited listcruftisation is continuing, attracted by the tempting list. I've therefore taken the bull by the horns and removed it. The article is already perfectly well illustrated with examples sufficient to make its point; the list is by its own admission permanently incomplete, of indefinite size; and we're better off without it. Sorry but there it is, we've tried hard to make use of it, but it's incompatible with having this as a decent article. Chiswick Chap (talk) 15:50, 22 September 2018 (UTC)

- I agree entirely. @Manudouz: as I said above, there could in principle be an article "List of paraphyletic taxa" but each and every entry would need to be sourced. Peter coxhead (talk) 16:33, 22 September 2018 (UTC)

Non-human animals

"Animal" in most languages is informally used by laypersons to exclude humans: compare definitions 1 and 2 here <https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/animal>. As such, the common non-scientific use of "animal" to mean "non-human animal" is generally paraphylitic. Is it worth including this as a linguistic note? 95.184.99.80 (talk) 09:47, 23 April 2019 (UTC)

- If you find a source explicitly noting it as paraphyletic, then addition could be considered. CMD (talk) 14:01, 23 April 2019 (UTC)

- It would be odd to call this group "paraphyletic", which is more usually used when the removed clade has an obvious recent last common ancestor with the remaining taxa. ("Apes", meaning Hominidae minus Homina, are an obvious example.) Peter coxhead (talk) 15:12, 23 April 2019 (UTC)

- What do you mean by that? Humans form a clade with with chimpanzees, with a more recent ancestor than with the other apes. CMD (talk) 10:57, 24 April 2019 (UTC)

- It would be odd to call this group "paraphyletic", which is more usually used when the removed clade has an obvious recent last common ancestor with the remaining taxa. ("Apes", meaning Hominidae minus Homina, are an obvious example.) Peter coxhead (talk) 15:12, 23 April 2019 (UTC)

- Humans share a common ancestor with all other animals so animals (used in that exclusionary common usage) are paraphyletic with respect to humans. But animals would never be used that way in a phylogenetic study and paraphyly only has meaning in a phylogenetic context. Jts1882 | talk 14:33, 24 April 2019 (UTC)

Requested move 27 October 2023

- The following is a closed discussion of a requested move. Please do not modify it. Subsequent comments should be made in a new section on the talk page. Editors desiring to contest the closing decision should consider a move review after discussing it on the closer's talk page. No further edits should be made to this discussion.

The result of the move request was: withdrawn by nominator. (closed by non-admin page mover) — Ceso femmuin mbolgaig mbung, mellohi! (投稿) 15:23, 1 November 2023 (UTC)

Paraphyly → Paraphyletic groups – More directly describes the thing we're trying to document. It seems to me that the current name complicates defining the concept. Isaac Rabinovitch (talk) 02:46, 27 October 2023 (UTC)

- Oppose At present, the name parallels Monophyly and Polyphyly, so there's no logic that I can see in changing one without the other two, and I'm not convinced that changing all three titles would achieve anything.

- I do agree, however, that there are issues with the three "phyly" articles. The problem, in my view, is not the title of the article, but the separation of the three. It's not possible to understand one concept without the others. Peter coxhead (talk) 06:30, 27 October 2023 (UTC)

- Interesting point. If you want to turn this into a discussion of merging the three articles, I'm fine with that. Can we start with discussing what the merged article would be called? Isaac Rabinovitch (talk) 15:24, 27 October 2023 (UTC)

- @Isaac Rabinovitch: you've identified the problem! The idea of merging has been discussed on and off for years, but there's never been a good idea for a title that I've seen. Peter coxhead (talk) 06:29, 28 October 2023 (UTC)

- Interesting point. If you want to turn this into a discussion of merging the three articles, I'm fine with that. Can we start with discussing what the merged article would be called? Isaac Rabinovitch (talk) 15:24, 27 October 2023 (UTC)

- Weak oppose I think it better to have the articles on the concept, but it doesn't matter too much as long a the quality of the article is high. I'd also agree that the subjects might be better served by one broader article. As an aside, I note that the Monophyly article treats monophyly and holophyly as equivalent and starts the definition of monophyly with Hennig rather than Haeckel. Even if one accepts Hennig's redefinition, it should be discussed. — Jts1882 | talk 10:28, 27 October 2023 (UTC)

- Re the older/alternative view of terminology, I've long wanted to get the table at User:Peter coxhead/Work/Phyletic terminology#Comparison of terminology into an article, but it didn't really seem to fit when we have three articles. Certainly the non-Hennig use should be discussed; it relates to paraphyly as well as monophyly. Peter coxhead (talk) 06:40, 28 October 2023 (UTC)

- I'd support including that table and agree it fits better within a broader article. Have you seen these papers by Mats Envall (2008; doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.00984.x) and Damien Aubert (2015; researchgate)? I don't pretend to understand the latter, but with your background you might. — Jts1882 | talk 08:45, 28 October 2023 (UTC)

- The Mats Envall paper I have seen, but not the Aubert paper, which is interesting. The problem (for me) is that Aubert is just one of a number of authors who have produced consistent and water-tight definitions of the "phyly terminology", but there's no evidence that the wider community of biologists have taken any notice. Thus if you try to write about how the terms are actually used, you run into problems. We spent quite a lot of time discussing this on Wikipedia about 10 years ago now. Sigh... Peter coxhead (talk) 09:26, 28 October 2023 (UTC)

- I approve Aubert's point 7: "The desire for taxonomic stability should be reaffirmed by explicitly prohibiting the use of paraphyly ... as a pretext to change the delimitation of a taxon. It is an irrelevant criterion." Sadly I see no likelihood of this being adopted. Peter coxhead (talk) 11:32, 28 October 2023 (UTC)

- I'd support including that table and agree it fits better within a broader article. Have you seen these papers by Mats Envall (2008; doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.00984.x) and Damien Aubert (2015; researchgate)? I don't pretend to understand the latter, but with your background you might. — Jts1882 | talk 08:45, 28 October 2023 (UTC)

- Re the older/alternative view of terminology, I've long wanted to get the table at User:Peter coxhead/Work/Phyletic terminology#Comparison of terminology into an article, but it didn't really seem to fit when we have three articles. Certainly the non-Hennig use should be discussed; it relates to paraphyly as well as monophyly. Peter coxhead (talk) 06:40, 28 October 2023 (UTC)

- Pretty strong consensus against my proposal. I don't think we need to wait 7 days to close this. Isaac Rabinovitch (talk) 18:17, 28 October 2023 (UTC)

"most" descendants?

The article starts out by saying that "Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and most of its descendants", but it isn't clear how the cyan patch in the diagram to the right, said to be a paraphyly, contains "most" of the descendants of the last common ancestor. "Most" in what sense? 2A00:23C8:7B0C:9A01:3E:A303:E9E2:6E46 (talk) 15:27, 20 March 2024 (UTC)

- It would be better to say most of the descendant lineages, although I'm not sure most is correct in all cases. The diagram is trying to show several things at once which makes it less clear that the paraphyletic group includes two of the three main lineages. — Jts1882 | talk 16:08, 20 March 2024 (UTC)

- On that basis, I changed it to "the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages". If this is definitely worse than the previous text then please put it back. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 2A00:23C8:7B0C:9A01:5930:A740:C4C4:BD56 (talk) 23:01, 21 March 2024 (UTC)