Sarah Collins Fernandis

Sarah Collins Fernandis | |

|---|---|

| Born | March 8, 1863 Port Deposit, Maryland, US |

| Died | July 11, 1951 (aged 88) Baltimore, Maryland, US |

| Occupation(s) | Social worker, educator, writer, settlement worker |

Sarah A. Collins Fernandis (March 8, 1863 – July 11, 1951) was an American social worker, writer, and community leader, based in Baltimore, Maryland. She organized settlement houses in Washington, D.C., and Rhode Island, and worked for improved living conditions and healthcare for Black city residents.

Early life

Sarah Collins was born in Port Deposit, Maryland,[1] during the American Civil War, and raised in Baltimore, the daughter of Caleb Alexander Collins and Mary Jane Driver Collins. Her father worked at a lumberyard after the war, and her mother was a laundress.[2] She earned an undergraduate degree from Hampton Institute in 1882, and a master's degree in social work from New York University.[3] She wrote the lyrics to the Hampton Institute alma mater.[4]

Career

Collins taught school for about twenty years, in Virginia, Maryland, Tennessee, Georgia, and Florida, sometimes under the auspices of the Women's Home Missionary Society of Boston.[1] She organized and led the Colored Social Settlement House in Washington, D.C., in 1902.[5][6] She later was head resident at another settlement house in East Greenwich, Rhode Island from 1908 to 1912.[7][8] She improved the houses and their neighborhoods with libraries, classrooms, clinics, playgrounds,[2][9] childcare, events,[10][11] and even basic banking services.[12]

She was founder and president of the Women's Cooperative Civic League in 1913,[13] and during World War I she organized a War Camp Community Center for Black soldiers stationed in Pennsylvania.[14][15] In 1920, she became the first Black social worker employed by the Baltimore public health department.[3] She organized to establish the Henryton State Hospital for Black tuberculosis patients. She retired from the city health department in 1933, but opened a National Youth Administration office in 1936, to help place homeless young women in employment and housing.[2] She also lectured for the National League of Women Voters, lobbied for compulsory school attendance laws and for quality low-income housing.[16]

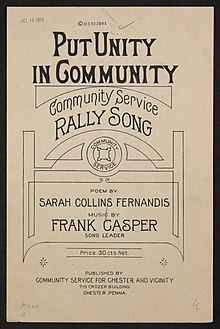

Fernandis wrote songs for her educational and community-building work, and her poems were often published in the Southern Workman.[17][18][19] She published two volumes of poetry, Poems and Vision, in 1925.[1][9]

Personal life

Sarah Collins married barber John Fernandis in 1902. Sarah Collins Fernandis died in 1951, aged 88 years, in Baltimore.[3][20] There is a room at the YMCA in Baltimore named for Fernandis.[2]

References

- ^ a b c Sturgill, Erika Quesenbery (February 10, 2013). "Sarah Collins Fernandis: Pioneering social worker from Port Deposit". Cecil Whig. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ a b c d Hollie, Donna Tyler (2013). "Fernandis, Sarah Collins". Oxford African American Studies Center. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.35626. ISBN 9780195301731. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ a b c Peebles-Wilkins, Wilma (2013-06-11). "Fernandis, Sarah A. Collins". Encyclopedia of Social Work. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.686. ISBN 9780199975839. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ "Alma Mater". Hampton University. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ Fernandis, Sarah Collins, "A Social Settlement in South Washington" in The Negro in the Cities of the North (Charity Organization Society 1905): 64-66.

- ^ "Social Settlement". Evening Star. 1905-01-02. p. 10. Retrieved 2021-02-11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hess, Jeffrey A. (July 1970). "Black Settlement House, East Greenwich, 1902-1914" (PDF). Rhode Island History. 29: 113–127.

- ^ Streich, Catherine (2020-08-02). "Reform – What Went Wrong? Scalloptown, Part Two". East Greenwich News. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ a b Smith, Jessie Carney (1992). Notable Black American Women. VNR AG. pp. 221–223. ISBN 978-0-8103-9177-2.

- ^ "Colored Babies' Day". Evening Star. 1905-06-10. p. 3. Retrieved 2021-02-11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Christmas Presentation". Evening Star. 1906-12-21. p. 19. Retrieved 2021-02-11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "She is their 'Bank Lady'". The Kansas City Star. 1904-10-18. p. 4. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ Who's who of the Colored Race: A General Biographical Dictionary of Men and Women of African Descent. 1915. p. 102.

- ^ "Mrs. Fernandis in War Work". The New York Age. 1919-01-18. p. 2. Retrieved 2021-02-11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ White, Newman Ivey; Jackson, Walter Clinton (1924). An Anthology of Verse by American Negroes. Trinity College Press. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-0-598-60639-6.

- ^ "Lifting as We Climb: African American Social Welfare Pioneers of the Progressive Era", an online exhibit featuring Fernandis and her contemporaries, created by Boston College Libraries

- ^ Honey, Maureen (2006). Shadowed Dreams: Women's Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance. Rutgers University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8135-3886-0.

- ^ Fernandis, Sarah Collins (May 1922). "Love's Service". The Southern Workman. 51: 231.

- ^ Fernandis, Sarah Collins (August 1914). "Music". The Southern Workman. 43: 439.

- ^ "Writer of HI Song Dies, 88". Daily Press. 1951-07-12. p. 12. Retrieved 2021-02-12 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

- "Put Unity in Community" (1919), rally song; lyrics by Sarah Collins Fernandis, music by Frank Casper; sheet music in the Library of Congress

- Iris Carlton-LaNey, African American leadership: An empowerment tradition in social welfare history (NASW Press, 2001) ISBN 9780871013170; includes a chapter on Fernandis

- Lorraine Elena Roses, Ruth Elizabeth Randolph, eds., Harlem's Glory: Black Women Writing, 1900-1950 (Harvard University Press 1996) ISBN 9780674372696; includes "A Blossom in an Alley", a poem by Fernandis

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Articles with hCards

- Articles with ISNI identifiers

- Articles with VIAF identifiers

- Articles with WorldCat Entities identifiers

- Articles with LCCN identifiers

- 1863 births

- 1951 deaths

- People from Port Deposit, Maryland

- American social workers

- American women poets

- American educators

- American women in World War I

- Hampton University alumni