Religion of the Shang dynasty

| Religion of the Shang dynasty | |

|---|---|

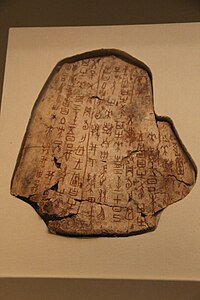

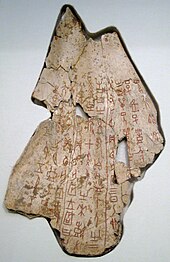

An ox scapula inscribed with the results of divination[1] | |

| Theology | |

| Region | Yellow River valley |

| Language | Old Chinese |

The state religion of the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC) involved trained practitioners communicating with deified beings, including deceased ancestors and supernatural gods.[3] Primary methods of spiritual veneration were written divinations on oracle bones and sacrifice of living beings. The Shang dynasty also had large-scale constructions of tombs,[4] which reflects their belief in the afterlife, along with sacred places. Numerous Shang vessels, as well as oracle bones, have been excavated in the kingdom's capital Yin.[5][6] They reveal a large number of honoured deities, most of which came from the Shang's extensive observations of the surrounding world. Headed by the god Dì, the deities formed a pantheon.

The Shang kingdom's religion, accounting for a large portion of court life, played an important role to its adherents. The deities worshipped received various honorary ceremonies. The Shang astronomers created a sophisticated calendar system based on astronomical observations.[7] Complying with the calendar, diviners and sacrificial practitioners conducted liturgical rituals aimed at the gods. Regional practice became existent, as personal estates maintained independent practitioners. Generally, they all worshipped the same deities for common purposes. Mass offerings to gods, formalized over time, were held for divine support and welfare of the state.

The Shang religion originated in the Yellow River valley, heartland of the Chinese civilization from 1600 to 1046 BC,[a] and was the first thoroughly documented Chinese religion. Although its writing script is much older, the first inscribed oracle bones of this religion date from c. 1250 BC,[11] during the reign of Wu Ding (c. 1250 – c. 1200 BC) [12][13][14] and over 1000 years before the end of ancient China in 221 BC. Throughout over two centuries, the dynasty increased its cultural influence and experienced cultural exchanges by means of war. After 1046 BC, the Zhou dynasty, which replaced the Shang,[9][10] gradually assimilated elements of Shangdi into its governing beliefs.[15][16] Over the following millennia, many elements of the ancient religion were reflected in the later religious system of the Zhou dynasty, as well as the systems of imperial China (221 BC – 1912 AD). Shàngdì remains an important figure in Chinese culture, and the calendar originally used for religion is now important in traditional events of China and influenced countries.

Beliefs

Dì

The highest of the Shang gods was Shàngdì ̣(上帝),[17] full form Dì (帝).[18][19][b] In many oracle bone inscriptions, Dì is described as a being who controlled natural forces as if controlling individual spirits in a hierarchy, which made him distinguished from the other worshipped gods.[18] Dì did not give messages in preserved scriptures, and his will could only be known through oracle bones.[21] There are various abilities attributed to the high god, mostly described on oracle bones not directly but through pairs of affirmative and negative statements.[18]

Dì exercised authority over the natural world by giving commands (lìng 令).[15] The Shang kingdom's economy was based on agriculture, which relied heavily on climatic patterns. The Shang people believed that the weather was controlled under the power of Dì, writing a lot on predictions about his decisions. Dì also dictated harvests,[15] and sometimes could supply humans with foods if proper "calling out" rituals were conducted. This god could give military supports by many ways, for example by indirectly helping royal forces in conquering hostile states, by protecting the Shang king in royal inspections, or by forecasting divine will to support by sending natural phenomena such as rains. [15] Furthermore, he was the power that gave approvals (ruò 若) to humans' everyday decisions and actions, including constructions and army marches; unusual occurrences were perceived as signs of Dì's disapproval.[15][18] The Shang also believed that although Dì could aid them in various aspects, he could also harm them by his power. Numerous Shang texts record disastrous events thought to be caused by Dì's will, including droughts, defeat by enemies, or even the king's health deterioration.[15] The Shang offered sacrifices and carried out divinations to ensure Dì was appeased and to avoid calamities.

Dì's identity has been a subject of debate.[22]This system of structured spirits featured him as the apex, hence making him corresponding with the "leading" role of Zeus in Ancient Greece and Tiān in Zhou dynasty.[23] There are many proposed approaches for this god's identification.

Some scholars link Dì with the existence of the Emperor Ku,[24] who was mentioned in Sima Qian's Shiji as the Shang dynasty's progenitor,[23][16] and who was addressed "High Ancestor" in more than four oracle bone inscriptions. Many prominent scholars support the view that Dì and Ku actually represent an identical power. Its implications for the current understanding of the religion's theology are additionally profound. Some historians assert that if the Shang system of gods featured the highest and supreme deity as a primal ancestor of the rulers, then the monarchs themselves would be acceptedly seen as possessing divine powers. In other words, the kings would be perceived as embodying the power of Dì (or Ku), being the "thearchs" by birth.[25]

There is another explanation, derived from studies of Dì in linguistic contexts, that the religion did not possess a "High God" in its pantheon and that Dì was a generic word for the collectivity of all divine powers.[18][26] This suggestion partly results from debates among scholars on the presence of the word Dì in ancestral titles. Some claim that Dì could not be a part of Shang ancestors, no matter how distant. Oracle bones indicate that Dì could destroy the Shang capital, which Robert Eno perceived as impossible to be done by royal ancestors, reliant on sacrifices which were mostly conducted in the capital. Eno also argued that since Dì was included in some ancestral titles, then if it referred to a High God, the ancestors must have been perceived as rivaling Dì in power, which he considered unlikely. He proposed a suggestion to explain this: Dì was generic, referring to no specific god but to all the spirits including ancestral deities.

Natural powers

The Shang people paid particular attention to the winds compared to other natural occurrences, and associated them with the phoenix.[27] The Shang identified four wind gods, corresponding to four types of wind, and assigned each god for a direction (eastern, western, southern, northern).[27] These four winds as well as responsible deities together represented Shàngdì's cosmic will, carry Dì's authority to affect agriculture, and were regularly prayed to for successful harvests.[28] Ceremonies were conducted to appease the wind gods for favour in royal hunts, or to determine the message carried by unusual winds,[27] sacrificing dogs and hounds.[23] Although there were wind gods, the Shang still separated them from harmful winds, which were given rituals that keep them away.[27]

Because the country's agriculture was of crucial importance, the Shang people deified and worshipped many deities whose natural manifestations affected productivity. In particular, the "God of Earth" (Shě or Tǔ), with possible feminine gender,[29] was associated with protection from misfortune.[30] This deity might be manifested in the human world by representation of the Shang's tribal neighbour Tǔfāng, with which the Shang maintained agricultural relationships.[28]

The Shang natural cult also included a mountain power (岳),[31] whose rituals were done at the site itself. The Sun, especially during the setting and rising periods, was treated as a "guest" sent by Dì to the Shang king. Aside from that, Shang rituals also aimed at clouds, rains, snows, and even the River deity, although their mentions in oracle bones decreased over time. Importantly, spirits assigned to these locations were able to wield destructive powers, manifested through events like floods.

Ancestral powers

The Shang dynasty established a complex ancestral cult.[c] They identified six foremost ancestral spirits: Shàng Jiă (上甲), Bào Yǐ (報乙), Bào Bǐng (報丙), Bào Dīng (報丁), Shì Rén (示壬), Shì Guǐ (示癸); meanwhile, the royal line with kingly sovereignty started from Shì Guǐ's child Dà Yǐ (Chéng Tāng) and progressed to the last king Dì Xīn. The nearest previous generation of the monarch had spirits responsible for the monarch's well-being. Kings like Wu Ding were highly religious, believing that their health depended heavily on appeasing ancestral spirits, and often dreaming about them.[33] Their rituals, therefore, was aimed at their immediate predecessors and conducted for the purpose of solving personal issues.[18] Power of ancestral spirits, accordingly, varied in correlation with their seniority, and thus they were treated to some extent differently. The earlier the time frame of the ancestors, the greater their impact on the state. Shàng Jiǎ and his subsequent five predynastic leaders were addressed the "Six Spirits", and were thought to be the beings who dictated harvests.[18]

There were several mysterious spirits addressed as ancestors, whose identity has not been fully comprehended. There were "Former Lords" like Wáng Hài (王亥)[34][35] and Náo (獶),[36] whose names are pictographic characters.[37] There were also similar individuals revered along ancestors like Yī Yǐn and Mò Xǐ .[38][39][40]

Ancestresses were also revered along with their male counterparts. Oracle bone inscriptions mention some of the most important female Shang ancestors, who were grand royal consorts of the kings. Inquiries to female deceased individuals illustrate beliefs in their spiritual role. They were perceived as being unfriendly and angry on some occasions, and after such divinations they received offerings.[41][42][43][44] Some females who were mentioned in oracle bone divinations are, as demonstrated by oracle bone inscriptions:[18]

- Bǐ Jǐ (consort of Zǔ Yǐ ): "We shall protect the King's eyes against Grandmother Jǐ ."

- Bǐ Gēng (consort of Xiăo Yǐ ): "The King's son met with disaster on account of Mother Gēng."

- Bǐ Bǐng: "We shall perhaps pray to High Grandmother Bìng for a child."

- Fu Hao: grand consort of Wu Ding. She received a greater degree of veneration than other females after her death. She was referred to by her posthumous names "Mother Xīn" and "Ancestress Xīn".[45][46][47]

Cosmology

The Shang believed in the divinity of an area surrounding the Ecliptic Pole, featuring a square shape (oracle bone script: 口). Observations of the sky made by astronomers and astrologers focused on a square of over four stars surrounding the pole at the time of the Shang dynasty, whose inscriptions contain implicit meanings considering their perception of a divine cosmos. "口" also denoted the modern stem "ding",[d] and used in many collocations with personal titles such as Xiōng, Zǔ or Fù,[e][28] This shape also seemed to have been used as model in temple designs.[50]

Taotie faces

The Taotie motif, which featured regularly on historical Chinese cultural artefacts, was present during the Shang dynasty.[51][52] The Shang taotie motif depicts spirits through representation of animals,[53] a tradition inherited from synthesizing earlier cultures' designs like Yangshao and Liangzhu.[28][54][55][56] While some speculate the taotie motif to have conveyed no meaning to the Shang rather than serving for decorative purposes,[57] most of the evidences point out that this was indeed a centrally religious aspect.[58][28] Scholars claimed that since the taotie appears on Shang ritual vessels and ceremonial axes,[59] it was not carved for decorations. Several interpretation of the specific meaning of taotie to the Shang have been given.[60] These taotie faces all bear strong resemblances with the polar area concerned in Shang cosmology. For example, the Shang taotie features nasal ridges surrounded by dots, a similarity to the ecliptic pole and its adjacent stars. John C. Didier asserted that these similarities indicate that the depicted figures were divine spirits with crucial importance to the Shang people.

Shàngdì and Xiàdì

The Shang dynasty believed that Dì was bipolar, that is, he was divided into two counterparts, of which Shàngdì was the heavenly representation. Shàngdì, as Dì's component, was a manifestation of the sky through the polar square.[28] In the Shang people's perception, the counterpart Shàngdì was housed by the sacred northern pole.[61] Also in Shang beliefs, indicated by oracle bones, this squared polar area on the sky, containing the god's cosmic divinity, was composed of main-lineage ancestral spirits through the generic name Shàngdì,[28][62] representing Dì's will to act favourably towards humans. Already in oracle bone script, there are two frequent characters depicting Shàngdì,[63] one features the squared shape at its centre, and the other has two horizontal parallel lines, which in turn was associated with heavenly divinity and thus to the square itself.[64][65]

Conversely, the Shang believed that Shàngdì, as Dì's manifestation of "heaven", had a negative counterpart associated with "earth". Many character versions depict the earthly counterpart of Shàngdì, named Xiàdì, composed of adopted deities and opposing people, and represented Dì's negative actions towards the human realm.[28] For example, one of Shang's long-term opponent, the Tǔfāng ("Earth Territory"), seemed to have been seen as a part of Xiàdì themselves. Therefore, Dì was believed to be both Shàngdì – heaven and positive – and Xiàdì – earth and negative,[28] which was why he possessed the power to cast destructive power on the Shang.

Practices

The Shang dynasty's religion centered on systematic rituals that influenced traditional Chinese rites. Main Shang rituals include divination, liturgical sacrifices, invoking prayers, and funerals. Often, the Shang accompanied these with ritual music and dances in religious sanctuaries.

Divination

Divination was one of the most important aspects of the Shang religion. Oracle bones, which consist of ox scapulae, tortoise plastrons[3] and carapaces, were the main materials for divinatory documents.[f][g] The oldest bone texts were radiocarbon dated to c. 1254 – 1197 BCE, belonging to Wu Ding's reign.[13] The king and his court wrote about various topics, including warfare, agricultural successes, personal well-being, and weather.[3][h][i] Because Shang gods exercised power over human actions,[71] numerous divination rituals were held by the king[72] (and his court scribes (多卜)) to acquire godly assistance. Writers inscribed inquiries on the bones, then heated the bones and interpreted bone cracks. Inquiries (or "charges") contain particles implying desired preferences,[73] and some contain more detailed information such as verification.[74] On many oracle bones, the king and his scribes prognosticated upcoming days that were thought to be "unanimous".[18][75][j] The Shang's mature calendar system was used for denoting and arranging days on oracle bones.[77]

丁丑卜,暊貞:其示(?)宗門,告帝甲暨帝丁,受左

"Divined on dingchou day, Fu tested: When handing over [unstated object] (at) the gate of Ancestral Temple, making announcement to Dì Jiǎ together with Dì Dīng will receive disapproval."

Divination during Geng Ding's reign, for deceased kings Zu Jia and Wu Ding.[78]

Many Shang divinations were concerned with warfare. It was characterized by numerous military expeditions to all directions, especially to Guifang.[79][80][81] Regional governors, who had their local commoners serving as military conscripts, were required to prepare to assist the royal army in combat.[82] Divination was made to determine the regional chief suitable for countering enemies. Numbers mattered significantly: the Shang inquired about the sufficient number of soldiers to gain advantages, and the number of war captives they could obtain.[23] Military officers' responsibilities were determined by oracle bone consultation. [23] Response to the questions were used as orders for the officials' mobilization of the army. Aside from these, prognostications about enemy offences also featured themselves on bones. In a particular case, a prediction claimed that "disasters" would be brought upon the state; five days later, the Tǔfāng destroyed two walled Shang cities.

Additionally, divinations were carried out to determine suitable days for construction of regional city walls, which was important to defend the area's urban centres from foreign invasions. Conscripts from personal fiefs were recruited to carry out such buildings.[23] Court civil officers, tasked with agriculture, received orders decided by divination to monitor agrarian activities. Some texts include divinatory responses which required the responsible officials (sometimes the kings) to make farmers plant grains or to supervise cultivation of crops in newly opened lands. The kings also divined occasionally about issuing orders to supervisors of craftsmen.

It has been recognized that there are divinations not made on behalf of the king.[83][84]The aristocracy could have specified groups of diviners. Wu Ding's son or nephew,[85][86] whose oracle bones lie in modern-day Huāyuānzhuāng East, made divinations on affairs happening in his estate; his inscribed bones numbered up to 537,[87] containing personal divinations and bone receipt records.[88] For example, one of the prince's inscribed divinations inquires about construction of an ancestral temple tended to store tapestries for Fu Hao's upcoming visit.[89][90] Another oracle bone inscription describes the supervision of completing his land's guesthouse used to store sacrifices. Counts of modern scholars show that the prince honoured more than 20 royal ancestors in his inscriptions.[91][92][93][94]

Liturgical sacrifices

The Shang religion is a typical example of a sacrificial system. Sacrifices were offered mainly to seek divine support or for the gods' appeasement.[95] The Shang paid particular attention to the number of beings sacrificed.[96]

The sacrifices that were not living beings were mainly bones, jade, and bronzeware items. Some of the bone products were shaped into hairpins or arrowheads. The tomb of Fù Hǎo contains over 560 such bone products. Jade was present through inheritance with previous cultures in China proper, such as Longshan and Liangzhu.[97] The material was treated as precious, and sometimes the jade sacrifices were buried with their initial royal owners. Bronze came in plenty;[98] the number increased during the Wu Ding period, which saw a major advancement in bronzemaking technologies.[99]The offering ceremonies involved bronze vessels with short inscribed characters.[72][100] If the sacrifices were intended to be accompanying the dead in their tombs, bronze weapons (like arrows and spears) together with decorative products could be added. At the last Shang capital Yin, thousands of bronze items have been unearthed, revealing the importance of this metal in Shang's procedure of honouring. There were also other minor materials that came in much smaller amounts. In particular, stones, ivory and even cowry shells were sacrificed.[101]

Some species of animal, after being hunted,[102] served as offerings (犧牲),[103][101] both to the ancestral and supernatural sections of the religion's pantheon.[104] There are four types of animal sacrifices, regarding position and completeness.[105] Usually, canine species were killed to be consumed by both natural and ancestral deities,[106][107][18] often by means of body dismemberment. The way they were offered seemed to have no effect on divine actions. Sheep were intended for a wide range of ancestors, spanning through generations from the progenitor Shàng Jiǎ to much nearer ancestors like Pán Gēng. Other animals that were offered include oxen, goats and elephants buried in royal tombs,[101] the latter served as a source of ivory. These sacrifices became increasingly institutionalized among social classes.

The Shang dynasty also practised human sacrifice.[108] Guo Moruo asserted that people were sacrificed on a large scale.[109][110] However, the source of humans served for this purpose was not the state's citizens; instead, the court sacrificed neighbouring polities' people who had been previously captured in battles.[111] The Shang usually obtained a large number of captives, a small percentage of which were spared to be slaves, with most expected to produce religious artefacts. The rest, including women,[112][113] were killed and their remains sacrificed to Shang ancestors. A single sacrifice alone could require hundreds of individuals killed,[114] some numbered up to thousands.[115][k] Regarding subjects for offering, the Shang did not distinguish the opponent's common people from their leaders, the latter were often reserved for highly honoured ancestors. Human sacrifices to supernatural deities (except Shàngdì) were subject to rules of offering. The people sacrificed had to be buried when the recipient was the earth deity, drowned when offered to water spirits, and dismembered when offered to wind spirits.[117]

Sacrificial terminology

Examples in various oracle bones show different names designated for specific types of sacrificial subjects. For example, animals offered would be called xisheng (犧牲), and humans called rensheng (人牲). There are plenty of Shang terms used specifically for female human sacrifices. Such women were designated nü (女 'females'), while the more specific qi was used to refer to 'dependent women'. Fu referred to captives of war, such as the Qiang. Shang scribes added prefixes to those indicatives, often to differentiate their origins; usually, names of the tribes from which humans were caught would be used for this purpose. There are numerous other particular terms that Shang used to designate types of humans offered to spirits.

Some oracle characters denote terms for general sacrificial methods. For example, the Shang word for dou (豆) refers to methods of killing sacrificial humans in bronze vessels,[118] while shan (刪) was used to mention a single human slaughtered. The Shang wrote shi (氏) for ritualized offering at temples.[119]

Liturgical year of sacrifice

In every day of a Shang week, a deceased ancestor would be chosen to be the recipient of specific sacrifices. On the guǐ day, the weekend, the reigning king and his assistants specialized in rituals would make a typical inscription that announced the sacrifices for the next day.[120] A year was sectioned into three periods, the first of which usually lasted 13 xun.[120] The first third was to perform ji, zai and xie sacrifices, the second for yong sacrifice, and the last for yi sacrifice. At the beginning of each third, a common ceremony honoring all the targeted recipients (gong dian) was held.[120] Some argue that ji was the opening ritual.[121]

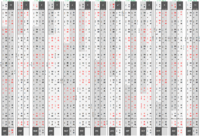

In his 2011 work, Adam Smith tabled the sacrificial schedule of the late Shang practitioners, inscribed on a group of oracle bones by Huáng, a scribe living during the reign of the last three kings.[7] During this period, the Shang's planned sacrifices evolved into a liturgical year of 36 weeks. Five "opening" weeks were intended to announce upcoming rituals. Each sacrifice commenced the week right after the announcing one. The thirty-sixth week was left blank as to prepare for a new offering cycle.[122]

Using recording texts of Chū and Huáng (living at different periods), A. Smith also found out about the rules of arranging days for sacrifices. The Shang specified every royal ancestors to the certain days, and many other rules were made to fairly distribute the offerings between the days.[123] The basic principle is that one's stem name would dictate his or her chosen day of sacrifice; other rules structured the schedule in an orderly way.

Shamanism

Inscriptions on Shang oracle bones suggest a complicated religious system which communicated with the spiritual world via ritual performance (bin 賓) and the utilization of "numinous" media like bones and bronze.[124] This type of communication, as some scholars point out,[18] can be interpreted as communication "without direct encounter". Other interpreters of Shang ritual bronzes, such as K.C. Chang, assert that this perception is not satisfactory, and that the Shang dynasty's religion must have borne considerable shamanic elements.[125]

Studies of oracle bone script yielded a character that corresponds with the later term "wu"[126] (巫 'shaman').[127][128][129] Nevertheless, the roles of wu during the Shang dynasty is yet to be fully clarified.[130] It is uncertain whether the Shang "wu" actually referred to shamans, who get into altered states of consciousness, or to another kind of practitioners who used other practices to communicate with the spirits. Victor Mair supported the view that the wu of the Shang dynasty resulted from earlier connections with western Asia.[131] He examined archaeological and linguistic evidences, and concluded that the Shang "wu" was etymologically and culturally related to the Zoroastrian "maguš",[l] denoting priests that communicated with spirits through rituals and manipulative arts rather than shamanic characteristics like trance and mediation. David Keightley also disagreed with the interpretation of the Shang "wu" as "shaman".[132]

Funerary practices

The largest place for the afterlife lay in the Royal Cemetery, located in what is now Xibeigang (西北岡), Anyang, serving as the resting place for many royal family members. The king would be buried in a wooden chamber, with his attendants, animals and bronze products such as vessels and weapons.[133] Burial subjects were interred in designated positions relative to the deceased's coffin, with each position bearing a specific meaning. Several tombs also served for the purpose of rites, and were topped by ancestral shrines.[134] Wu Ding's reign in the 13th century BC saw the cemetery's partition into the East and West zones, as a result of polishing Wu's image as a distinguished Shang king.[4]

Using radiocarbon dating and other techniques, researchers have constructed a list of genealogy of the individuals buried. The study reports of Koji Mizoguchi and Junko Uchida, published in 2018, reveal that the Royal Cemetery's tombs were intended to built in a complex manner that indicates the buried individuals' relationships to each other.[4] Some tombs bear striking resemblances, which the authors interpreted as attempts to imitate virtuous royal ancestors by the kings.[4] Studying the cemetery's overall structure, scholars also pointed out that Xibeigang tombs' positions harmoniously aligned with the northern celestial pole, which housed the power of the ancestors in the form of a collective Shàngdì.[28]

Around 1046 BCE, the last Shang king Di Xin lost the decisive Battle of Muye[10] in which his forces was crushed by the Overlord of the West, Ji Fa. Di Xin set fire to his palace and committed suicide. The fact that he was not buried in accordance with Shang's tradition was due to his immoral image made up by the Zhou dynasty.[135]

Posthumous naming

Aside from the supernatural beings, the ancestors of the Shang kings were also revered. The recipients of honours included both dynastic and pre-dynastic ancestral individuals, honoured with were given posthumous names.[120] The religion used a structured system of naming kings, which uses calendrical names for days.[137][9] There were 10 weekdays whose names were used for ancestors: jia (甲), yi (乙), bing (丙), ding (丁), wu (戊), ji (己), geng (庚), xin (辛), ren (壬), and gui (癸).

There were several religious rules that dictate the naming decision.[7] The Heavenly Stems used as one's title had to be the first day of his reign (in the Shang calendar). Besides, the king restrained from having gui as his posthumous name.[120] If the first year of reign began with gui, the next day jia was used as an alternative. For distinguishing different kings with the same stem name, a set of prefixes was used, each of the prefix carried a specific meaning. Royal consorts of the Shang kings were given stem names not compliant with limitations as for the kings.[138]

Posthumous names have strong connections with the ancestors' attributed powers. The majority of Shang ancestors possess names with the stems jia, ding and yi, which represent celestial divinity.[28] By being referred to by such stems, the spirits became perceived as powerful gods whose will significantly affected the living realm.

Some prefix indicates the addressed subject's familial relationship with the reigning ruler, and often with a much broader sense than their modern meanings:[123]

- Relatives who were two or more generations before the incumbent ruler would be referred to as zǔ (祖) (for males) and bǐ (妣) (for females). In this context, zǔ means (great) grandfather or patrilineal great uncle; bǐ means grandmother and other consorts of zǔ. Sometimes, zǔ could be used officially as the posthumous name's first component.

- The previous generation: fù (父) was used for males and mǔ (母) for females. The masculine indicative means the father or paternal uncles, while the other denotes the mother or the father's other wives.

- The same generation: only the character for males has been found, which is xiōng (兄, "older brother"). This word could also be applied to paternal cousins.

- The next generation: the king's sons and nephews were referred to as zǐ (子). The word is sometimes understood as the surname of the rulers, while some understand it as "Prince".[139]

Temples

The court employed officials to plan and carry out constructions of sacred places. The general design of temple compounds (zong 宗) consisted of an elevated hall (tang 堂), a courtyard (ting 庭), a gate ( men 門), and sacrificial pits (keng 坑).[140] Temple designs generally seemed to have connections with beliefs in the celestial square. Chen Mengjia saw the word 口 as a notation for an altar;[m] others also see it as a kind of temple ritual.[142] Wang Guowei offered that 口 resembled an ancestral tablet (dan 匰) and an altar or shrine to an ancestor (shi 祏).[143] Didier further pointed out the connection by noting that the squared form features twice in the Shang character 'temple' (宮).

The king and his priests were responsible for hosting temple praying rituals, sometimes using foreign labour for preparation processes. It was a prerogative of the Shang king, as the chief priest, to perform special prayers aimed at invoking spirits; in fact, the rituals' common name portrays the king praying in a sanctuary holding ritual objects.[144] Additionally, praying ceremonies involved many dancers, mediators and scribes, who were granted exclusive access to the sanctuaries. Different temples were intended for hosting deities; for example, the Great Altar (大示) hosted Shang royal members of the main lineage.[28][145] There were also separate temples, each reserved for a single spirit. Rituals were on a regular basis,[28] sometimes with ritual music.

Practitioners

The Shang king was seen as the religious apex. He actively involved himself in communication with the pantheon's gods by praying, divining and hosting rituals. The king would try to assure that the spirits would give him guidance.[18] The Shang court had a developed bureau for assisting the ruler; it consisted of several groups, each of which was specialized in a specific aspect. The officials include:[146]

- Diviners (duobu 多卜), supervised by a chief diviner (guanzhan 官占). They worked with shamans (wu 巫). Many were named on bones.[147] These practitioners were also tasked with documenting the rituals.

- Astronomers (xi 羲, he 和) and astrologers (shi 史), tasked with determining days and months. They also made observations of Mars and many comets, a notable achievement.[148]

- Dancers (wu 舞), and music directors (gu 瞽). As inscriptions show, they danced holding oxtails.[149]

It is agreed that religious professions of the Shang had to be acquired through forms of schooling.[150][151] Texts written by Wu Ding's scribal officials contain the word 學 'to learn'[152] that could act both as a verb and a noun; in most cases it comes with an important musical ritual called shang.[150] The two characters imply that the subjects were being trained for musical roles. In terms of religious literacy training, there are inscriptions described by Guo Moruo as "finely written and orderly, as though engraved by a teacher (xiānshēng 先生) to serve as a model (fànbĕn 範本)". There is another interpretation: the learners must have already known the characters and practiced writing them just for learning engraving techniques;[153] however, some scholars argue for its impossibility. There are also other suggestions.[154] It is also generally believed that the Shang might have had some kinds of institutionalized training locations for religious teaching.[155][156][157][158][159]

Regional practices

Religious activities during the Shang dynasty was not restricted to the urban area of Yinxu. There are instances of regional practice, although they are vague and much less known than the largest cult center at the capital city. Divinatory practices were present at the pre-Yinxu city in present-day Zhengzhou,[3] where four separated oracle bones inscribed with characters have been excavated. These inscriptions are relatively short and have a similar style to Yinxu writings. Other than Zhengzhou, oracle bones have also been unearthed in Jinan[160][161][162] and Shaanxi, the original homeland of the Zhou dynasty, and believed to be from the last decades of the Shang's existence. Additionally, many oracle bones have been found in river management constructions.

Religious constructions were commissioned by royal members in areas outside of the royal domain at Yinxu. The prince possessing the Huayuanzhuang oracle bones resided in Rong, a conquered region by the Shang dynasty and was probably west of Anyang, and ordered an ancestral temple with spirit tablets to be built there.[163] He made sacrifices with both local and imported materials.[163] This prince also authorized several relatives to participate in sacrifices, ale libations, and musical rituals.[164] The king at the time, Wu Ding, allocated to him resources such as sacrificial prisoners and grains.

It is believed that common people during this period played a role in religious activities. There are possibilities that the populace might have participated in seasonal festivals and sacrificial offerings.[165] Commoners might as well have been involved in religious activities carried out by regional lords.

Effect on royalty

Kingship and sovereignty

The Shang king entrusted lords to govern Shang provincial regions; they were ordered to assist him in important affairs. Many of the lords were initially chiefs whose lands had been conquered and merged into Shang's territorial extent.[n] The royal house nominally possessed the lords' lands – in fact, the kings always referred to all the regions as "our lands" – but he largely depended on the lords' loyalty.[o] Kingly sovereignty over the lords is argued to have resulted from the spirits whom the king worshipped.

Scholars have studied Kuí (夔), a mysterious deity,[23] and presented a theory suggesting that Kuí's cult was the result of incorporating other beliefs. As Shang's neighboring polities themselves gradually submitted, their gods were "adopted" by the Shang religion and treated equally with Shang spirits. The king's role helped him keep the regional chiefs' loyalty by mediating among the spirits of both their gods and his own.

The nature of kingship was also derived from the deified beings. Ancestors such as Shàng Jiǎ (and generally the Six Spirits) had great influences over important national affairs, like other non-ancestral deities. In other words, they were universal deities. The Shang kings could be considered (and claimed to be)[170] "living deities on earth".[p]

Favor of masculinity

"Crack-making on jiashen day, Que divined: Fu Hao will give birth; it will be favorable. The King prognosticated saying: if she gives birth on a geng day it will be very auspicious. [Verification] After thirty-one days, on day jiayin, she gave birth. It was not favorable; it was a girl.

Divination by Que, during Wu Ding's reign.[172]

The system furthermore affected the continuation of kingship. The Shang tradition allowed female individuals to participate in government; however, it was overall a patriarchal society.[173] Influences of male ancestors overwhelmed that of their feminine counterparts in scale. The person responsible for functioning as head of the clan and head of religious practice had to be a male. Males would carry the ancestral surname "Zi" and pass it to subsequent generations.

Conception of male children was considered a serious matter by the Shang dynasty, which expensed a considerable of divinations on this aspect. Ancestral intervention played a role in deciding the children's gender. Oracle bones show that the Shang considered another factor, the birthday, to be related to gender formation. In particular, the conception of Fu Hao, Wu Ding's second primary consort, was of interest to his court. Diviners carried out numerous divinations all predicting the baby's birthday.[23]; occasionally, verifications were also inscribed, as demonstrated in the particular bone inscription by Wu Ding's diviner Que.

History

Precursors

Before the dawn of organized states in China, the area was inhabited by various tribal confederations. Each of the tribes practiced its own system of beliefs. The religious beliefs in prehistoric China were based on ideas of animism, totemism and shamanism.[175][176][177] Many ancient tribes in pre-dynastic China shared a common belief in the spiritual world.[q] The spirits were thought to possess divine powers. As such, they were able to intervene in and dictate the lives of the living realm's beings. That led to the necessity of direct communication with the spirits, through means of mystics. A group of specified individuals, known as shamans, arose and took responsibility for conducting their respective tribe's religious rituals.[179] The cultures in the future heartland of the Shang dynasty had practiced sacrifices and funerals.[180][181][r] In many regions of China, Neolithic cultures had utilized bony materials from cattles for divination.[3][183][184][185]

In the Zhou dynasty's historical narrative, the tradition of honoring and venerating deities had already been existent during the Shang's predecessor Xia dynasty (c. 2070 – 1600 BCE).[186][s] The Book of Documents also mentions the Shang high god Shangdi receiving annual sacrifices by Emperor Shun, even before the Xia dynasty.[191] Although these periods are often considered mythical, their corresponding site of Erlitou (c. 2100 – 1500 BCE) has evidence of bronze-using religious activities that were later adopted and developed by the Shang dynasty,[57] such as ancestral temples and sacrifice.[192]

Shang dynasty

The Shang dynasty's religion inherited the characteristics of its predecessors. Its beliefs, rituals of sacrifices and funerals bore resemblances with those of prehistoric beliefs. Early Shang kings created bureaucratic positions for religious practice, which were later diversified and further specialized. The religion was widespread, influencing other major Shang cities aside from Yinxu.[7][193]

During the late Shang period (1300 - 1046 BCE), the religion achieved its mature status. Many kings of the late Shang were deeply religious and actively involved themselves in those matters. Some monarchs made alterations to the tradition. The first notable change took place during Wu Ding's regnal era. This change was documented by the Book of Documents, compiled centuries after its supposed time.[194] Oracle bone script from the mid-12th century BC indicate that Wu Ding's youngest son Zu Jia also altered sacrifices.[195] Changes also occurred in practitioners. Gradually, diviners of the Late Shang period were divided into schools, each of which were employed by several late Shang kings. Modern scholars classify Shang diviners by two methods based on periodization[196][197] and employment.[198][199][200] Both ways group diviners into two main schools.

The Shang kingdom showed religious interactions with other cultures in China proper. In most cases, the religious influences of the Shang dynasty left an impact on its vassal states. For example, the vassal Dapeng also practiced human sacrifice[201][202] and also included the Earth Power Sheji (or Tǔ) in the Shang pantheon into their list of worshipped deities.[203][204] From the 1200s BCE onward, religious influence of the Shang reached its largest vassal state Zhou. The polity embraced Shang theology into its beliefs, and the Shang also likely included Zhou dead ancestors into the collective Dì godhead as well.[205]

Evolution under the Zhou

In 1046 BCE, the Shang dynasty under the regime of Di Xin collapsed and was replaced by the victorious Zhou dynasty. This succeeding dynastic family used the practices of Shang religion to explain Di Xin's fall. The Book of Documents contains a chapter claiming that Di Xin discarded all the sacrificial traditions and therefore lost the blessings of his royal ancestors[206][t] as well as of the Zhou supreme god.[209]

Calendar

The Shang liturgical calendar was adopted by the Zhou,[u][212][213][214] although it is uncertain whether the Zhou court reset the day counting after the dynasty's establishment.[215][216] It was greatly revised and altered through the regime's eight centuries of existence. The diversification of its use took place during the Warring States period when cultural distinctions became more apparent.[217] The Shang name for the count of years, si (祀), was replaced by the Zhou term nian (年) which originally meant "harvest" but whose meaning was altered.[218] Uses of calendrical means by the new regime's kings was more complex than their predecessors Shang in that astronomical observations became integrated extensively to calculate and predict important forthcoming events.[219] The Zhou monarchs invented a different terminology and separated methods for their own ancestors' veneration.[7] A new system for posthumous naming dead relatives was devised, based on the virtues of rulers; still, some people during the early Zhou used the old tradition, including exceptional Zhou kings.[220][221][222]

Worshipped deities

The head of the Shang pantheon, Dì, became assimilated and identified with Heaven (Tiān) of the Zhou dynasty,[79] while still keeping its original meaning in early Zhou times. Through time, the original figure and the Shang-attributed powers of Dì was forgotten, since Heaven was more philosophically complicated and was associated with more terminology as well as legendary tales. But overall, "Tiān" still recalled Dì's meaning as a driving force of the kings' reigns: the Mandate of Heaven, invented by the Zhou dynasty,[223][224] was the key concept of a monarch's right to rule over the country[225][226] up until the end of monarchy in China in 1912 CE.[227] Dì was identified with the Jade Emperor by practitioners of Taoism; also possibly, the counterpart of Shàngdì became transformed into the form of the Yellow Emperor during the Zhou dynasty.[228] During imperial Chinese dynasties, the tradition of "Sacrifice to Heaven" became popular, and Shàngdì was made the main recipient of the event's sacrifices. In 221 BCE, when Qin Shi Huang created the title "Emperor" for himself,[229] he combined Dì with the character Huáng (皇, "august") to obtain the term.[230]

The early Western Zhou kept the Shang tradition of inscribing, on oracle bones, inquiries to Shang ancestral deities, such as Dì Yǐ,[231] indicating their former status as a state recognizing Shang suzerainty over them.

Other practices

There is evidence that religious activities of the state of Chu during the Eastern Zhou were related to the Shang religion, due to similarities between their artistic motifs. Mass human sacrifices practiced by Shang was critically reduced, though still employed.[232][233] Oracle bones gradually ceased to be inscribed once the Zhou dynasty began, and the regime compiled a new way of divination and prediction, the I Ching (written between the 10th and 9th century BC).[234] The populace in later dynasties practiced different funeral and sacrificial traditions,[235] mainly due to the influence of Confucianism, Taoism, and other currents; however, there were still some parallels between the two dynasties regarding sacrifices.[236] The role of women in religion notably changed after Shang.

Legacy

The Shang high god Dì remained to the present day through his heavenly component Shàngdì, who is still worshipped in countries of the Sinosphere. The word "Shàngdì" is sometimes used to denote the Christian God,[237][238][239][v] and the Jade Emperor.[240]

Traditional festivals in China, Vietnam and other influenced countries make use of the sexagenary cycle.[241] The lunar calendar's organization of days names the years, months,[242][w] days and even hours after the 10 Heavenly Stems and 12 Earthly Branches. There are various folk tales attributed to this calendrical system, many of which appeared much later.

The Shang rituals left behind a bronze-using tradition that deeply influenced later religious activities. Bronze vessels produced by the Shang dynasty constitute greatly to the cultural heritage of ancient Chinese civilization. Additionally, they also include bronze inscriptions, one of the first two written forms of Chinese, providing insights into epigraphic studies of the language.

Assessments by Chinese dynasties

After the end of the Shang, various Chinese dynasties have presented their perceptions about the religion. While there are praises, especially by those who held favorable views on traditional values of the past, there are also thorough assessments and even different interpretations of Shang religious activities.

Zhou dynasty

During the Western Zhou period, the perception of Dì and Shàngdì, as presented, was mixed with that of Tiān. Already in the very earliest years of Zhou, Dì had been seen as accompanied by Zhou ancestors. During king Wu's reign (1046 – 1043 BCE), Zhou officers inscribed on a tureen about King Wen of Zhou assisting Dì on high.[x][243][244] Dì and Tiān were used interchangeably in the same inscriptional contexts. For example, King Li of Zhou (reigned 857 – 842 BCE),[245] commented on the power of Shàngdì:

The king said: I am but a small child, yet unstintingly day and night, I act in harmony with the former kings to be worthy of august Tian .... [I] make this sacrificial food vessel, this precious kuei-vessel, to succor those august paradigms, my brilliant ancestors. May it draw down the spirits of those exemplary men of old, who now render service at the court of Di and carry forth the magnificent mandate of august Di...

The Book of Documents, one of the most important Chinese classical texts composed during the Zhou dynasty, critically presents the Zhou's interpretation of various Shang religious practices. For example, the text points out the important of ancestral reverence to the Shang rulers, in that ancestral spirits exercised great authority over the living. Pan Geng was described in the Book as a perspicacious ruler, believing in the powers of the Shang high ancestor Táng to send down calamities on unworthy men. Additionally, this text highlights Shang divination by shells and bones, by referring to alleged events such as Pan Geng emphasizing on his officers who did not "presumptuously oppose the decision of the tortoise shell".[247]

Many texts also evaluate Shang sacrificial traditions' alleged negative sides. The Shujing, or Book of Documents, quotes:

"Dignities should not be conferred on men of evil practices. (If they be), how can the people set themselves to correct their ways? If this be sought merely by sacrifices, it will be disrespectful (to the spirits). When affairs come to be troublesome, there ensues disorder; when the spirits are served so, difficulties ensue."

— Book of Documents, "The Charge to Yue".

The Book quotes from an alleged minister of Wu Ding named Fu Yue, saying that sacrifices were sometimes conducted on unsuitable occasions when they were counterproductive. The Liji also contains a similar passage, which asserts that Shang sacrifices should have been made in the right times.

Some Zhou people also mentioned the lack of available Shang religious texts, which caused inadequate understanding of their rituals. Confucius, in particular, asserted that the documents preserved by the Shang dynasty's royal members in Song were not enough for him for an extensive comprehension of the ancient ceremonial codes.[248]

Han dynasty

Han dynasty historian Sima Qian, writing 1,000 years after the Shang dynasty's collapse, commented about its religiosity. He wrote that the Shang had practiced different traditions from the Zhou, and had been, on the extreme level, superstitious.[249] He also noted about various Shang kings who received spiritual advice from their ministers, such as the case of Wu Ding (with his minister Fu Yue) and Tai Wu (with his minister Yi Zhi). They were possibly men with shamanic capabilities. Sima Qian went on to describe the sacrificial rituals of the Shang dynasty, commenting on virtuous kings who emphasized on worshipping high ancestors, and detailing the negative impacts of ignoring the gods (Wu Yi,[250] Di Xin).

By the time of the Han dynasty, the perception of the god Dì had been significantly altered. While the character retained its meaning as "High Deity", it was used mainly as a prefix or suffix to add to another word for deifying its meaning. Some examples from Han dynasty texts containing such combinations are Huángdì and Yāndì. Nevertheless, the Han dynasty also worshipped a cosmologically associated god titled Shàngdì, whose divinity was similar to that believed by the Shang dynasty. In particular, the Han-era Huainanzi, a compilation of debates led by imperial prince Liu An, presents an interpretation of Dì: "The Celestial Thearch stretches out over the four weft-cords of Heaven...". This god also lay on a polar referential star like in Shang dynasty, the star Kochab (Beta Ursa Minoris). Han texts identify Dì with Tàiyǐ (太一), the "Great One".[251] Believed by the Han people as having been worshipped by the early Zhou kings, Dì (or Tàiyǐ) was highly revered.

Sima Qian, in chapter 27 of his work, stated that his attempts to identify the celestial power of Dì used references from Wuxian, the early Shang mediator. Wuxian was believed to be one of the most notable Shang religious figure, and a revered astrologer. He was positively viewed in other Han and post-Han texts, and his attributed star maps were often used in Chinese astronomy.

Notes

- ^ The periodization 1600 to 1046 BCE is given by the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project.[8] However, many other possible suggestions have been proposed. Most of them place the Shang dynasty's beginning date around 1550 BCE, while deviating the end date for a few years.[9][10]

- ^ Zhu Fenghan has challenged the notion that Di was the Shang supreme god, arguing that this deity was in fact a cosmic spirit newly invented by the Shang.[20]

- ^ It has been argued that the Shang ancestral cult was intended for the ancestors to lead other spirits to act favourably towards the human realm, that is, to "domesticate the spirits and thereby render them controllable".[32]

- ^ Xu Zhongshu asserted that the square represents the oral expression of the Shang stem "dīng"[48]

- ^ The connection of Shang lineal descent to the square is noticeable and has been argued by Qiu Xigui.[49]

- ^ Other materials for pyromancy have also been found[69]

- ^ Oracle bones were probably obtained through tributary polities of the Shang kingdom, since the material was not native to its region.[70]

- ^ Most divinations about weather, agriculture or wars were made by Wu Ding's court.

- ^ Many divinations were bu xun (卜旬) 'divining for the week ahead'. The diviners would predict events for the next ten-day week after the said divination.

- ^ It has been observed that many Shang texts omit these parts. Chinese researchers such as Xiao Liangqiong have reconstructed divinations from fragments.[76]

- ^ According to Robert Bagley, there are tombs that contain up to 1,200 human corpses.[116]

- ^ Old Chinese reads "wu" as myag (Bernhard Karlgren),mjuo < *mjwaɣ (Zhou Fagao), *mjag (Li Fanggui), mju < *ma (Axel Schuessler).

- ^ The obvious connection between the square and Shang deified ancestors has led to the theory that the Shang character that has two squares as denoting a temple. However, it has been known that that character only refers to a place where the Shang king hunted, or his non-religious residence.[141]

- ^ The Shang king also conferred rights to his relatives as estate owners, but he could also take away these authorities[166]

- ^ Regional governors shared benefits with the king by being bestowed rewards[167][168][169] in exchange of investing effort in helping him.

- ^ Ancestors bearing names which resemble the Celestial Square were probably spirits of cosmic divinity.[171]

- ^ Some prehistoric Chinese cultures produced artifacts that bear the "AZ" motif, which represented some kind of a "High God" similarly to the Shang dynasty's Di.[178]

- ^ An example is the Longshan culture, which practiced human sacrifice.[182]

- ^ The second monarch of the Xia dynasty, 啟; Qǐ or 開; Kǎi:,[187] was described as a shamanic intermediary connecting with the supreme deity Shangdi (上帝).[188][189][190]

- ^ Archaeological evidence supports their claim: oracle bone inscriptions from Di Xin's reign indicate that his court ignored discerning Di's will and performed ancestral sacrifices methodically ineffective. [207] It is also observed that the weekly sacrificial schedules established by Zu Jia had been mostly abandoned during Di Xin's reign.[208]

- ^ It is able to demonstrate the geographically distributed nature of the day-name tradition towards the end of the 2nd millennium BC.[210] An example is a cemetery at Gaojiapu, in Shaanxi.[211]

- ^ Matteo Ricci first coined the term "Shangdi" to denote God in Chinese.

- ^ There are two systems for recording months in this way.

- ^ Original bronze inscription c. 1046 BCE: 乙亥,王又(有)大丰(豐),王凡三方,王祀于天室,降,天亡又(佑)王,衣祀于王,不(丕)显考文王,事喜上帝,文王德才(在)上,不(丕)显王乍省,不(丕)□(?)王乍庸。不(丕)克气衣王祀,丁丑,王乡(饗),大宜,王降,乍勋爵后□,隹朕又蔑,每(敏)杨王休于尊簋。 Translation by Robert Eno (2012): On the day yi-hai the King conducted a great ceremony. The King set off by boat, sailing in three directions. The king performed a sacrifice at the shrine of Heaven and then descended. Tian Wang aided the King, who then performed a grand sacrifice to the King’s great and brilliant father, King Wen, who pleases with service Di, Lord on High. King Wen looks down from above. With the great and brilliant King surveying above, the great and upright King carried on below and brought to a grand close the sacrifice to his father. On the day ding-chou the King held a banquet with a great meal of meats. The King bestowed upon me, Wang, a vessel of rank... and I was praised. Earnestly do I raise up the grace of the King to my exalted Elder.

References

Citations

- ^ Chen, Kuang Yu; Song, Zhenhao; Liu, Yuan; Anderson, Matthew (2020), Reading of Shāng Inscriptions, Springer, Shanghai People's Publishing House, pp. 227–230, ISBN 978-981-15-6213-6

- ^ Chang (1983)

- ^ a b c d e Keightley (1978a).

- ^ a b c d Mizoguchi & Uchida (2018).

- ^ Bai (2002).

- ^ Wilkinson (2022).

- ^ a b c d e Smith (2011a).

- ^ Lee (2002), p. 28.

- ^ a b c Keightley (1999).

- ^ a b c Pankenier (1981–1982).

- ^ Boltz, William G. (February 1986). "Early Chinese Writing, World Archaeology". Early Writing Systems. 17 (3): 420–436.

- ^ Takashima (2012).

- ^ a b Liu et al. (2021).

- ^ Imperial China: The Definitive Visual History. New York: DK and Encyclopedia of China Publishing House. 2020. ISBN 978-0-7440-2047-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Stefon (2010).

- ^ a b c Eno (2008).

- ^ Yao, Xinzhong (2000). An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-64430-3. Archived from the original on 2020-07-29. Retrieved 2015-11-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Eno (2010a).

- ^ Libbrecht, Ulrich (2007). Within the Four Seas--: Introduction to Comparative Philosophy. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-1812-2.

- ^ Zhu, Fenghan (1993). "Shang Zhou shiqi de tianshen chongbai". Zhongguo Shehui Kexue: 191-211.

- ^ Noss, Davis; Noss, John B. (1990). A History of the World's Religions. New York: MacMillan. p. 254. ISBN 9780023884719.

- ^ Chang, K. C (1976), Early Chinese Civilization: Anthropological Perspectives, Harvard-Yen ching Institute Monograph Series 23. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard-Yenching Institute, p. 156-159

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eno (2010b).

- ^ He, Bingdi (January 1975). The Cradle of the East: An inquiry into the indigenous origins of techniques and ideas of Neolithic and early historic China, 5000–1000 B.C. Chicago: University of Chicago. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-226-34524-6.

- ^ Pankenier, David. "A Brief History of Beiji 北極 (Northern Culmen), With an Excursis on the Origin of the Character di 帝". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 124 (2): 211–236. doi:10.2307/4132212. JSTOR 4132212.

- ^ Eno, Robert. "Was There a High God Ti in Shang Religion?". Early China 15. pp. 1–26.

- ^ a b c d Takashima & Li (2022).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Didier (2009).

- ^ Ding, Shan (2001), "Houtu Houji Shennong Jushou kao (shang)", Wenshi 55: 1-13

- ^ Cook, Constance A. (2006). Death in Ancient China: The Tale of One Man's Journey. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. p. 43. doi:10.1163/9789047410638_004. ISBN 9789004205703.

- ^ Thorp, Robert L. (2006), China in the Early Bronze Age: Shang Civilization, University of Pennsylvania Press, p. 83, ISBN 978-0-8122-3910-2

- ^ Puett, Michael J. (2002). To Become a God: Cosmology, Sacrifice, and Self-Divinization in Early China. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674009592.

- ^ Hu, Houxuan. Jiaguxue Shangshi luncong chuji. Vol. 3. Chengdu: Wenyoutang shudian.. Hu Houxuan interpreted numerous divinations sought to understand dreams by Wu Ding, from dreams about ancestors to sacrificial animals.

- ^ Luo, Yun (1998). "Yin buci zhong gaozu Wang Hai shiji xun yi". In Zhang, Zhongshan; Hu, Zhenyu (eds.). Hu Hengxuan xiansheng jinian wenji. Kexue chubanshe. p. 48-63.

- ^ Zhang Guangzhi (張光直) (1983), 談王亥與伊尹的祭日並再論殷商王制, 中國青銅世代 (in Chinese), Taipei: Lianjing chuban shiye gongsi

- ^ Liu, Huan (2002). "Shuo gaozu Nao - jianlun Shangzu zuyuan wenti". Jiaguzhengshi. Harbin: Heilongjiang jiaoyu chubanshe. p. 267-303.

- ^ Yu, Xingwu (November 1959). Lue lun tuteng yu zongjiao qiyuan he Xia Shang tuten. p. 60-66.

- ^ 伊尹 (in Chinese). china50k.com. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ^ Cai, Zhemao (1996). 伊尹傳說的研究. In Li Yiyuan 李亦園; Wang Qiugui (王秋桂) (eds.). 中國神話與傳說學術研討會論文集 (in Chinese). Taipei: Hanxue yanjiu zhongxin. p. 274. ISBN 9789576782039.

- ^ Chen Minzhen (陳民鎮) (2019). "Faithful History or Unreliable History: Three Debates on the Historicity of the Xia Dynasty". Brill Journal of Chinese Humanities. 5. Translated by Fordham, Carl G.: 78-104. doi:10.1163/23521341-12340073.

- ^ Heji 35361: female victims were offered to ancestresses. In Heji 35364 and 36276, women were sacrificed to both ancestors and ancestresses.

- ^ Yu Xingwu (2010). Jiagu Wenzi Shilin. Beijing: The Commercial Press. pp. 437–438.

- ^ Wang, Shenxing (1991). "Buxi suo jian Qiang ren kao". Zhongyuan wen wu (in Chinese). pp. 65–72.

- ^ Wang Shenxing (1992). Guwenzi yu Yin Zhou wenming (in Chinese). Xi'an: Shaanxi renmin jiaoyu chubanshe. pp. 113–114.

- ^ van Norden, Bryan (2003). "Oracle bone inscriptions on women 甲骨文". In Wang, Robin R. (ed.). Images of Women in Chinese Thought and Culture: Writings from the Pre-Qin Period through the Song Dynasty. Indianapolis: Hackett. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-87220-651-9.

- ^ Zhongguo shehuikexueyuan kaogu yanjiusuo (1980), pp. 34–38, col. pl. 1

- ^ Cao Dingyun 曹定雲 (1993), 殷墟婦好墓銘文研究 (in Chinese), Taipei: Wenjin chubanshe, pp. 105–124, ISBN 9789576681615

- ^ Xu Zhongshu (徐中舒), ed. (1998). 甲骨文字典). Chengdu: Sichuan cishu chubanshe.

- ^ Qiu, Xigui (1992). v. Nanjing: Jiangsu guji chubanshe. p. 296-342.

- ^ Lixin, Li (2004). 甲古文'口'字考释与洹北商城1号宫殿基址性质探讨. 中国历史文物 (in Chinese) (48): 11–17.

- ^ Woolf, Greg (2007). Ancient civilizations: the illustrated guide to belief, mythology, and art. Barnes & Noble. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-4351-0121-0.

- ^ Wang Tao (1993). "A Textual Investigation of the Taotie". In Roderick Whitfield (ed.). The Problem of Meaning in Early Chinese Ritual Bronzes. London: School of Oriental and African Studies. pp. 102–118. ISBN 978-0728602038. Wang Tao noted that the name "Taotie" was a mere adoption of a later Zhou term for the pattern. He warned that the meaning of the "taotie" as "greedy glutton" as now understood was inaccurate.

- ^ Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth (1998). "The Metamorphic Image: A Predominant Theme in the Ritual Art of Shang China". The Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities (70): 5–171.

- ^ Rui Guoyao (芮国耀) Shen Yueming (沈岳明) (November 1992). 良渚文化與商文化關係三例) (in Chinese). Kaogu.

- ^ Li, Xueqin (1993). "Liangzhu Culture and the Shang Dynasty Taotie Motif". In Whitifield, Roderick (ed.). The Problem of Meaning in Early Chinese Bronzes. Translated by Allan, Sarah. London: Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. pp. 56–66. ISBN 9780728602038.

- ^ An Zhimin (安志敏) (September 1997). 良渚文化及其文明諸因素的剖析. Kaogu (in Chinese): 77–83. An Zhimin, however, sees little connection between Liangzhu artefacts and those of Shang.

- ^ a b Bagley (1999a).

- ^ Loehr, Max (1968). Ritual Vessels of Bronze Age China. New York: Asia Society. ASIN B0013FYSHC.

- ^ Rawson, Jessica (1996). Mysteries of Ancient China, New Discoveries from the Early Dynasties (eds.). George Brazilier. ISBN 978-0-807-61412-9.

- ^ Chuanxin, Xiong. Zoomorphic Bronzes of the Shang and Zhou Period. Translated by Gillian Simpson. pp. 96–101.

- ^ Schuessler, Axel (2007). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawaii Press.. The Western Zhou (1046–771 BC) character for "Tian" also features the squared shape at its top.

- ^ In Shang, the dazong, or 'great lineage' of royal ancestors included kings whose father and son also were kings. This is usually referred to as the main lineage, while collateral-lineage kings were fraternally appointed.

- ^ Gao Ming (高明)) (1980). 古文字纇編. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

- ^ Zhou Fagao (周法高) (1974). 金文詁林 (in Chinese). Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- ^ Zhou Fagao (周法高) (1982). 金文詁林補 (in Chinese). Nangang: Zhongyang yanjiu yuan, Lishi-yuyan yanjiusuo.

- ^ Hu Houxuan, ed. (2009), 甲骨文合集释文, China Social Sciences Press, ISBN 978-7-5004-8462-2

- ^ Ma Rusen (馬如森) (2010), 甲骨金文拓本, Shanghai University Press, ISBN 978-7-811-18651-2

- ^ Liu, Xueshun (2005). The first known Chinese calendar: A reconstruction by the synchronic evidential approach (PhD thesis). University of British Columbia. p. 123. doi:10.14288/1.0099806.

- ^ Chou (1976).

- ^ Raven (2020).

- ^ Keightley (2004).

- ^ a b Qiu (2000).

- ^ Lefeuvre, Jean A. (1985). "Collections of Oracular Inscriptions in France". Cahiers de Linguistique - Asie Orientale. 16 (1). Paris: Ricci Institute: 163–167.

- ^ Alleton, Viviane (2012), "À propos des origines de l'écriture chinoise", in Alleton, Viviane; Maniaczyk, Jaroslaw; Schaer, Roland; Vernus, Pascal (eds.), Les origines de l'écriture (in French), POMMIER, p. 177-180, ISBN 978-2746506374

- ^ Xu (2002).

- ^ Xiao, Liangqiong (1986). "Buci wenli yu buci de zhengli he yanjiu". Jiaguwen yu Yin Shang shi. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe. p. 24-63.

- ^ Steele (2010).

- ^ Schwartz (2020), p. 55.

- ^ a b Creel (1970).

- ^ Taskin (1992).

- ^ Loewe M.; Shaughnessy, E.L., eds. (1999). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C. New York. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- ^ Sawyer & Sawyer (1994).

- ^ Ye Yusen (葉玉森) (1934), 殷虛書契前編集釋, Jiagu wenxian jicheng

- ^ Jin Zutong (金祖同) (1935), 殷虛卜辭講話, Jiagu wenxian jicheng

- ^ Yao Xuan. "3". Yinxu Huayuanzhuang dong di jiagu.

- ^ Chen Jian (陳劍) (April 2004). 說花園莊東地骨卜辭的丁 (in Chinese). Gugong bowuyuan yuankan. pp. 51–63.

- ^ Sun Yabing 孫亞冰 (2014). 殷墟花園莊東地甲骨文例研究 (PhD thesis). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe. p. 20-21.

- ^ For an analysis of Huayuanzhuang bone receipt inscriptions, see Smith, Adam D (2008), Writing at Anyang: the Role of the Divination Record in the Emergence of Chinese Literacy (PhD dissertation), UCLA, p. 262-273

- ^ Schwartz (2020).

- ^ Zhu Qixiang (2008), pp. 29-44. The Prince of Huayuanzhuang was Wu Ding's son, indicated in seven different oracle bones (though it is uncertain whether he was born by Fu Hao). Ten other inscriptions also confirm that the Prince's grandmother (and hence Wu Ding's mother) was consort Geng of Xiao Yi.

- ^ Wei Cide (魏慈德) (2006), 殷墟花園莊東地甲骨卜辭研究 (in Chinese), Taipei: Taiwan guji

- ^ Zhao Peng (趙鵬) (2007), 殷墟甲骨文人名與斷代的初步研究 (in Chinese), Beijing: Xianzhuang shuju

- ^ Lin, Yun (2007), 花東子卜辭所見人物研究, 古文字與古代史 (in Chinese)

- ^ Gu Yu'an (古育安) (2009). 殷墟花東H3甲骨刻辭所見人物研究 (MA thesis) (in Chinese). Furen daxue.

- ^ Julia Ching (1997). "Son of Heaven: Sacral Kingship in Ancient China". T'oung Pao (83): 28-29.

- ^ Campbell, Roderick B. (2020). Ritualized Violence, Sovereignty and Being: Shang Sacrifice.

- ^ Buckley Ebrey.

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006).

- ^ Chen (2018).

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich (2010). "jinwen 金文, bronze vessel inscriptions".

- ^ a b c Theobald (2018).

- ^ Mark Edward Lewis (1989). Sanctioned Violence in Early China. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 21. ISBN 9781438410739.

- ^ Zhou Ziqiang (周自強) (2000). 中國經濟通史 (General economic history of China. Vol. 1, Xian-Qin jingji (先秦經濟卷). Beijing: Jingji ribao chubanshe. ISBN 7801275489.

- ^ For the meaning of animal sacrifices, see Liu, Yiting; Lei, Xingshan (2020). "Shangxi muzang yongsheng chutan" [A study of animal sacrifice in Shang system burial]. Kaogu.

- ^ Flad, Rowan; Liu, Yiting; Lei, Xingshan; Wang, Yang (2020). "Animal sacrifice in burial: Materials from China during the Shang and Western Zhou period". Archaeological Research in Asia.

- ^ Li, Z. (2011). "Shang wenhua muzang zhong suizang de gousheng yanjiu erti (Two issues about dog victim buried in tombs of Shang culture)". Nanfang Wenwu (2): 100–104.

- ^ Li, Z.; Campbell, R. (2019). "Puppies for the ancestors: the many roles of Shang dogs". Archaeol. Res. Asia. 17 (17): 161–172. doi:10.1016/j.ara.2018.12.001.

- ^ Flad, Rowan (28 February 2010). "Shang Dynasty Human Sacrifice". NGC Presents. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 21 December 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ Yang Shengnan (May 1982). "Dui Shang dai renji shenfen de kaocha". Xian Qin shi lunwenji.

- ^ Yang Shengnan (1988). "Shang dai rensheng shenfen de zai kaocha". Lishi yanjiu (in Chinese). pp. 134–146.

- ^ Zhao (2011), p. 165.

- ^ Christian Schwermann; Wang Ping (2015). "Female Human Sacrifice in Shang Dynasty Oracle Bone Inscriptions". The International Journal of Chinese Character Studies. 1: 51–52. doi:10.18369/WACCS.2015.1.49.

- ^ Wang Ping, "Jiaguwen yu Yin-Shang renji, p. 24

- ^ Yu Xingwu (2009). Jiagu wenzi gulin. Vol. IV. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. p. 2969.

- ^ Keightley, David N. (2012). Working for His Majesty: Research Notes on Labor Mobilization in Late Shang China (ca. 1200-1045 BC). Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-557-29102-8.

- ^ Bagley, Robert (2008). "Anyang Writing and the Origin of Chinese Writing". In Houston, Stephen D. (ed.). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge University Press. p. 190-249.

- ^ a b Chang (2000).

- ^ Chen Mengjia (1988). Yinxu buci zongshu. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. p. 246.

- ^ Zhao (2011), p. 317-318.

- ^ a b c d e Nivison (1999).

- ^ Hu Houxuan; Hu Zhenyu. Yin Shang shi. pp. 166–167.

- ^ Chang Yuzhi (常玉芝) (1987). Shangdai zhouji zhidu 商代周祭制度 (Sacrificial system of the Shang dynasty) (in Chinese). Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe. ISBN 9787500400424.

- ^ a b Smith (2010).

- ^ For a notable study of this ritual, see Lei, Huanzhang (1998). Rong Geng xiansheng bainian danchen jinian wenji (in Chinese). Guangzhou: Guangdong renmin chubanshe. p. 156-163..

- ^ Chang, K. C. (1983). Art, Myth, and Ritual: The Path to Political Authority in Ancient China. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674048089.

- ^ Shima Kunio (島邦男) (1971). 殷墟卜辞綜類 [Concordance of Oracle Writings from the Ruins of Yin] (in Japanese) (2nd ed.). Hoyu. p. 418. OCLC 64676356.

- ^ von Falkenhausen, Lothar (1995). "Reflections of the Political Role of Spirit Mediums in Early China: The Wu Officials in the Zhou Li". Early China. 20: 279–300. doi:10.1017/S036250280000451X. S2CID 247325956.

- ^ de Groot, Jan Jakob Maria (1964) [1908]. The Religious System of China. Volume V, Book II. The Soul and Ancestral Worship: Part II. Demonology. — Part III. Sorcery. Taipei: Brill- Literature House (reprint). The author argued that "wu" in Chinese and "shaman" in Western languages are culturally different, and not compatible for translation

- ^ Schiffeler, John William (1976). "The Origin of Chinese Folk Medicine". Asian Folklore Studies. 35 (1): 17–35. doi:10.2307/1177648. JSTOR 1177648. PMID 11614235. The author argued that wu cannot be correctly translated in any way.

- ^ Boileau, Gilles (2002). "Wu and shaman". Bulletin of SOAS. 64 (2): 354-356. doi:10.1017/S0041977X02000149.

- ^ Mair (1990).

- ^ Keightley, David N. (1998). "Shamanism, death, and the ancestors: religious mediation in Neolithic and Shang China". Asiastische Studien. 52 (3): 783-831.

- ^ Rawson, Jessica; Chugunov, Konstantin; Grebnev, Yegor; Huan, Limin (2020), "Chariotry and Prone Burials: Reassessing Late Shang China's Relationship with Its Northern Neighbours", Journal of World Prehistory, 33 (2): 135–168, doi:10.1007/s10963-020-09142-4.

- ^ Thote, Alain (2009). "Shang and Zhou funerary practices: Interpretation of material remains (in French)". In Lagerwey, John (ed.). Religion et société en Chine ancienne et médiévale. Éditions du Cerf. p. 49-55. ISBN 9782204084000.

- ^ "规模宏大的安阳殷墟商代王陵(图)". Archived from the original on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ Takashima, Ken'ichi (2015), A Little Primer of Chinese Oracle-bone Inscriptions with Some Exercises, Harrassowitz, p. 2–4, ISBN 978-3-447-19355-9

- ^ Chang Zhengguang (常正光). 殷曆考辮. 古文字研究 6 (in Chinese). pp. 93–122.

- ^ Guo, Moruo. 甲骨文合集 (in Chinese).. In particular, the restraint from the use of gui did not affect the consort's posthumous names: one of Zu Ding's queens were posthumously titled "Yan Gui" (妣癸).

- ^ Boileau, Giles (2023). "Shang dynasty's "nine generations chaos" and the reign of Wu Ding: towards a unilineal line of transmission of royal power". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 86 (2). Cambridge University Press: 293–315. doi:10.1017/S0041977X23000277. S2CID 260994337.

- ^ Ulrich Theobald (2018). "Shang Period Religion".

- ^ Zhu Qixiang (朱岐祥) (1989). 殷墟甲骨文字通釋稿 (in Chinese). Taipei: Wenshizhe chubanshe. p. 264-265.

- ^ Yang Shuda (1954). Jiweiju jiawen shuo (in Chinese). Beijing: Zhongguo kexue chubanshe. p. 26-28.

- ^ Shima, Kenkyû: 178.

- ^ Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth (1995). "The Ghost Head Mask and Metamorphic Shang Imagery". Early China. 20 (20): 79–92. doi:10.1017/S0362502800004442.

- ^ Yang, Shengnan (1989). 殷墟甲骨文的河. 殷墟博物院院刊 (in Chinese). Vol. 1. pp. 54–63.. Yang Shengnan suggested that the Great Altar might not be only reserved for ancestral worship, pointing out a Shang inscription mentioning a ritual to the Yellow River performed at this temple.

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich (2018). "Shang Period Government, Administration, Law".

- ^ Jao Tsung-I (1959). Yindai zhenbu renwu tongkao. Vol. I. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- ^ Kerr, Gordon (2013). A Short History of China. Oldcastle Books. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84243-969-2.

- ^ Wang, Kefen (1985). The History of Chinese Dance. China Books & Periodicals. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8351-1186-7.

- ^ a b Smith (2011).

- ^ Yao, Xiaosui 姚孝遂; Xiao, Ding 肖丁 (1985). 小屯南地骨考釋 (in Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. pp. 197–206.

- ^ Gulin; see GL: numbers 3230–3233

- ^ Zhang Shichao (張世超) (2002). 殷墟⭢骨字跡研究— 師組卜辭篇 (in Chinese). Changchun: Dongbei shifan daxue chubanshe. pp. 27–28.

- ^ Olivier Venture (July 2002). Étude d'un emploi rituel de l'écrit dans la Chine archaïque (XIIIe–VIIIe siècle avant notre ère): Réflexion sur les matériaux épigraphiques des Shang et des Zhou occidentaux (PhD thesis) (in French). Université Paris. p. 308.

- ^ Oliver Moore (2000). Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 25.

- ^ Song Zhenhao (宋鎮豪). Wang Yuxin (ed.). 從⭢骨文考述商代的學校教育 (in Chinese). pp. 220–230.

- ^ Wang, Haicheng (2007), "Writing and the State in Early China in Comparative Perspective", Early China, 31: 322, doi:10.1017/S0362502800002078

- ^ Lee, Thomas H. C. (2000). Education in Traditional China: A History. Brill. p. 41. ISBN 978-9-004-10363-4.

- ^ Yang Kuam (楊寬) (2003). 西周史 (in Chinese). Shanghai renmin chubanshe. p. 664.

- ^ SHANDONG DAXUE LISHIXI (1995). Ji’nan Daxinzhuang yizhi chutu jiagu de chubu yanjiu. Wenwu 1995(6):47-52

- ^ SHANDONG DAXUE LISHIXI KAOGU ZHUANYE, SHANDONG SHENG WENWU KAOGU YANJIUSUO, and JI’NAN SHI BOWUGUAN. 1984 nian qiu Ji’nan Daxinzhuang yizhi shijue shuyao. Wenwu 1995(6):12-27

- ^ "Inscribed Oracle Bones of the Shang PeriodUnearthed from the Daxinzhuang Site in Jinan City". Chinese Archaeology. De Gruyter. January 2024.

- ^ a b Schwartz (2020), p. 47.

- ^ Schwartz (2020), p. 64.

- ^ Li, Liu; Chen, Xingcan (2012). The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64310-8.

- ^ Zhou Ziqiang (2000), p.189-190

- ^ Ma Honglu (馬洪路) (1994). 中國遠古暨三代經濟史 (in Chinese). Beijing: Renmin chubanshe.

- ^ Campbell, Roderick (2018). Violence, Kinship and the Early Chinese State. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Chang, Kwang-chih (1980). Shang Civilization. Yale University Press.

- ^ Li, Feng (2008). Bureaucracy and the State in Early China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88447-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ K. C. Chang (1982). Shang wang miao hao xin kao (A new study on the Shang kings' temple names 商王廟號新考). Hong Kong: Zhongwen daxue chubanshe. pp. 85–106.

- ^ Wang, Robin (January 2003). Images of Women in Chinese Thought and Culture: Writings from the Pre-Qin Period Through the Song Dynasty. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 9780872206519.

- ^ Campbell, Roderick (2014). "Animal, human, god: pathways of Shang animality and divinity". In Benjamin S. Arbuckle; Sue Ann McCarty (eds.). Animals and Inequality in the Ancient World. Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 251–274.

- ^ Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth (2023), "Continuation of Metamorphic Imagery and Ancestor Worship in the Longshan Culture", in Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth; Major, John S. (eds.), Metamorphic Imagery in Ancient Chinese Art and Religion, London: Routledge, doi:10.4324/9781003341246, ISBN 9781003341246

- ^ Łakomska, Bogna (2020). "Images of Animals in Neolithic Chinese Ceramics". Athens Journal of Humanities and Arts (7): 1-17.

- ^ Nelson et al. (2006).

- ^ Zhang & Hriskos (2003).

- ^ Du Jinpeng (February 1997). Liangzhu shenqi yu jitan (良渚神祗与祭坛). Kaogu. pp. 52–62.

- ^ Yang, Fenggang; Lang, Graeme (2012). Social Scientific Studies of Religion in China. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-18246-2.

- ^ Zhao, Chunqing (2013), "The Longshan culture in central Henan province, c.2600–1900 BC", in Underhill, Anne P. (ed.), A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, John Wiley & Sons, p. 250, ISBN 978-1-4443-3529-3

- ^ Nickel (2011).

- ^ Liu, Li (2005). The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81184-2.

- ^ Flad, R. (2008). Divination and Power: a Multiregional View of the Development of Oracle Bone Divination in Early China. Current Anthropology 49. pp. 403–437.

- ^ Gao Guangren; Shao Wangping, eds. (1986). "Zhongguo shiqian shidai de guiling yu quansheng". Zhongguo kaoguxue yanjiu bianweihui. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. p. 57-63.

- ^ Shi Zhongwen (史仲文) (1994), Hu Xiaolin (胡晓林) (ed.), 百卷本中国全史·远古暨三代宗教史 (in Chinese), vol. 5, Renmin chubanshe, ISBN 9787010014562

- ^ Sit, Victor F. S. (2021). "Xia Dynasty: Civilisation in the Early Bronze Age". Chinese History and Civilization: An Urban Perspective. p. 68.

- ^ Shanhaijing, "Classics of the Great Wastelands: West" 50 quote: "按:夏后開即啟,避漢景帝諱云。" rough translation: "Sidenote: Xia Sovereign Kai is Qi; [so called] to avoid voicing out the name of Emperor Jing of Han."

- ^ Shanhaijing, "Classics of the Regions Beyond the Seas: West" 4: "大樂之野,夏后啟於此儛九代;乘兩龍,雲蓋三層。左手操翳,右手操環,佩玉璜。在大運山北。一曰大遺之野。

- ^ Shanhaijing, "Classics of the Great Wastelands: West" 45 "西南海之外,赤水之南,流沙之西,有人珥兩青蛇,乘兩龍,名曰夏后開。開上三嬪于天,得九辯與九歌以下。此天穆之野,高二千仞,開焉得始歌九招。".

- ^ A Chinese bestiary: strange creatures from the guideways through mountains and seas. Translated by Richard E. Strassberg. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. (2002). pp. 50, 168-169, 219

- ^ Book of Documents, Book II: Canon of Shun