Moustached turca

| Moustached turca | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Rhinocryptidae |

| Genus: | Pteroptochos |

| Species: | P. megapodius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pteroptochos megapodius Kittlitz, 1830

| |

| |

The moustached turca (Pteroptochos megapodius) is a passerine bird which is endemic to Chile and belongs to the tapaculo family Rhinocryptidae. Common names of this species include "Turco" or "Turca". It is a terrestrial bird that burrows its nest on steep hillsides and uses flight for short distances. It is not threatened, yet it is unfortunately an understudied species of bird.

Taxonomy

The species name originates from the ancient greek μέγας, mégas \mé.ɡas\ and πούς, poús \pǒːs\, which translates to "big feet".[2][3]

The species was first described by Heinrich von Kittlitz during his voyage in 1830 on the Russian Senjawin expedition.[4] Since the species within the Rhinocryptidae family are very closely genetically related, their classification is mostly based on behaviour, ecology and plumage.[5][6] The genus of this species was initially referred to as Hylactes, but the official name Pteroptochos was retained shortly afterwards.[7] The moustached turca is a member of this genus along with two species of Huet-huet (Black-throated huet-huet and Chestnut-throated huet-huet) to which it is closely related.

Due to separate geographical location of occurrence and distinctive features, two subspecies have been recognized, the Pteroptochos megapodius megapodius (von Kittlitz, 1830) and the Pteroptochos megapodius atacamae (R. A Philippi-B, 1946).[8]

Description

The moustached is a stocky bird, approximately 22.5 cm (8.9 inches) long and a mass between 95–125 grams (3.4–4.4 oz). It has a heavy bill, cocked tail and disproportionately big feet, from which its name originates from. The adult plumage is mostly cinnamon brown with white barring on the breast, belly and undertail-coverts. The top of their head can appear gray-brown. They have a dark eyestripe, white eyebrow and a white broad stripe on the sides of the throat. The bill and legs are black in adults. Overall, the juveniles resemble the adults with differences being that juveniles have an unbarred rump and more fainted barring on the flanks. The plumage of females and males are alike, but size-wise the female is usually smaller.[8]

The atacamae subspecies is smaller, overall much paler and has whiter underparts in comparison to its sister subspecies.[8]

The only species it could be confused with is the white-throated tapaculo (Scelorchilus albicollis) which shares a similar environment. However, the tapaculo is smaller and does not have the distinctive white moustache of the turca.[8]

Habitat and Distribution

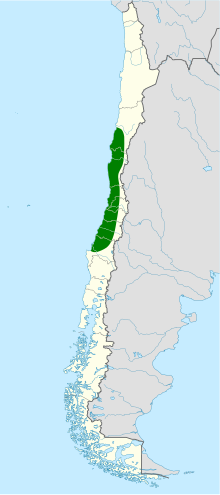

This species is endemic to Chile. The nominate subspecies, megapodius, is found in central Chile, from the center towards the southern limit. The isolated form, atacamae, occurs in the Atacama Region.[8]

All observations regarding reproductive individuals were found between the sea level and 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) in the foothills of the Andes. However, some non-reproductive individuals have been found at altitudes up to 3,200 metres (10,500 ft). Overall, the species can be found on hillsides with some shrubs and low tree cover. It prefers areas with low water content in the soil and in the case of the atacamae subspecies is only found in a semi-desert region with scattered rocks and boulders. More information is needed regarding its specific habitat requirements.[9]

Regarding its distribution, based on previous observations made by Reed (1904) and Passler (1929), the southern limit of the distribution was thought to be the Concepción region and the northern limit, the Coquimbo region. Since then, there have been many debates regarding these limits.[8] In 1946, Goodall et al.[10] suggested the northern limit as the Huasco river and reiterates that the southern limit is the Concepción region. In 2004, Marin[11] suggested Quebrado El León as the northern limit and Las Trancas as the southern limit. In the last couple of years, the northern limit has been narrowed down to the Parque National Llanos Challe using current eBird observations whereas the southern limit has been moved much more North than previously thought, in the region of Rauco. Observations of the moustached turca were not found South of the Rauco region. This concords with other records that suggest the distribution of this species was limited to the southern limit of the Constitución region before the forest plantations. Passler’s observations in 1929 in the Concepción region were probably of the black-throated huet-huet, Pteroptochos tarnii.[9]

Behaviour and ecology

It is a mainly ground-dwelling bird and can run quickly. It seldom uses its wings and only does so for short distance flights. It is preyed on by Harris's hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus), the bicolored hawk (Accipiter bicolor), the austral pygmy owl (Glaucidium nanum) and the barn owl (Tyto alba). There are no observations of predation on their eggs in their nest.[9]

Vocalizations

The moustached turca's repertoire is extensive. As of today, six vocalizations have been identified, the song, bubbling call, guerk, guk and the gweek. Its song is a series of low, hooting notes lasting for 5 to 10 seconds.[8]

The turca will mostly vocalize during the morning and at dusk, however song and calls can also be heard throughout the day. Typically, it will vocalize its song and bubbling call when perched on exposed rock, such as on top of high boulder, so as to make their voice resonate and be heard from a farther distance. Whereas other species within the Rhinocryptidae family have sex-specific vocalizations, it is still unknown if this applies to the moustached turca. Additionally, whether the vocalizations have different functions also remains unclear.[8]

Diet

The moustached turca feeds mostly on invertebrates such as insects and earthworms. They can also feed on seeds and fruits by displacing rocks and foraging near plants.[9]

Reproduction

They will start their nesting process in July and chicks will hatch between August and December. Adults have been observed to start their nests at the end of July. Some observations have been made of adults carrying food in the nest up until January, suggesting the rearing of young birds is still happening at that time.[9]

The moustached turca creates tunnels between 0.4–2.2 metres (16–87 in) deep in an earth bank on steep rocky hillsides (1)(2). No vegetation protects the entrance but due to the steep slope, it is presumed to be well protected from predators (1). At the end of this burrow is a cavity of approximately 25 centimetres (9.8 in) of width where the nest is found.[8][9]

The megapodius subspecies has slightly bigger eggs with a mean length of 35.3 millimetres (1.39 in) and width of 26.6 millimetres (1.05 in) in comparison to the atacamae, with respectively 32.1 millimetres (1.26 in) and 24.6 millimetres (0.97 in). Clutch size also varies between both subspecies, with the megapodius usually having 2 eggs with an occasional third and the atacamae having 3 eggs. All eggs are white.[8]

More research is needed on the post-reproductive behaviour of adults and juveniles.

Status of conservation

This species has been assessed by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2022 and categorized as Least Concern (LC).[12] Although the population size has not be quantified, researchers believe that the population is not vulnerable due to their stable range, maintaining itself above 20 000 km2 , and a population trend/size that is also stable.[12] There is no on going monitoring of this population nor are there any special measures in place, yet conservation sites have been identified within their home range.[12] These sites actively protect its habitat and include the Llanos de Challe National Park, Las Chinchillas National Reserve, La Campana National Park, Yerba Loca Nature Sanctuary, Parque Andino Juncal, Rio Clarillo National Park and Rio Cipreses National Reserve.[13]

Something to consider is that up until 2004, this species had been categorized under Unknown on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Additionally, information regarding population size, breeding, predators, sexual behaviour, and more are still limited or unknown to this day. Therefore, a fair assessment of the status of the moustached turca in these circumstances is difficult.

It is not classified under the Chilean Endangered Species Act, although it is illegal to hunt it in Chile.[8]

Threats

Although not in at risk, the main threat to this species is habitat destruction and fragmentation. In some of its range, specifically in the south, there is a strong expansion and development of cities accompanied by the conversion of shrublands to vineyards and avocado plantations.[9] As the landscape cover shifts into an agricultural setting, it will be important for wildlife managers to retain and maintain some native vegetation as these attract the local birds, which could include the moustached turca.[14] Additionally, the urbanization of previously undisturbed landscapes degrade habitat in an invisible way: the sound. The noise that accompanies cities has been identified as one of the barriers for native birds to occupy the spaces within these urban areas, regardless of specific habitat requirements.[15]

There is evidence suggesting that cats could possibly predate on this species (based on eBird observation) due to the moustached turca’s presence in proximity to cities.[8] This is also generally supported by literature as domesticated cats can venture far from their households when forest are in proximity, thus causing an increased risk to wildlife.[16]

External links

References

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Pteroptochos megapodius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22703431A93922705. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22703431A93922705.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "μέγας", Wiktionary, the free dictionary, 2023-08-26, retrieved 2023-10-10

- ^ "πούς", Wiktionary, the free dictionary, 2022-07-03, retrieved 2023-10-10

- ^ Kittlitz, F. H. v.; Kittlitz, F. H. v (1830). Über einige Vögel von Chili : beobachtet im März und anfang April 1827 / von F. H. von Kittlitz. [St. Petersburg: Académie impériale des sciences.

- ^ Terry Chesser, R (1999). "Molecular Systematics of the Rhinocryptid Genus Pteroptochos". The Condor. 101 (2): 439–446.

- ^ Correa Rueda, Alejandro; Mpodozis, Jorge; Sallaberry, Michel (2008-03-19). "Differences of morphological and ecological characters among lineages of Chilean Rhinocryptidae in relation an sister lineage of Furnariidae". Nature Precedings: 1–1. doi:10.1038/npre.2008.1606.3. ISSN 1756-0357.

- ^ Oberholser, Harry C. (1923). "Note on the Generic Name Pteroptochos Kittlitz". The Auk. 40 (2): 326–327. doi:10.2307/4073834. ISSN 0004-8038.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Medrano, Fernando; Krabbe, Niels; Schulenberg, Thomas S.; Boesman, Peter F. D. (2021-05-07), "Moustached Turca (Pteroptochos megapodius)", Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, retrieved 2023-10-11

- ^ a b c d e f g Medrano, F; Barros, R; Norambuena, HV; Matus, R; Schmitt, F (2018). Atlas de las aves nidificantes de Chile. Red de Observadores de Aves y Vida Silvestre de Chile. pp. 404–405. ISBN 9789560903914.

- ^ Zimmer, John T. (January 1947). "Birds of Chile Las Aves de Chile, su conocimiento y sus costumbres. Tomo Primero J. D. Goodall A. W. Johnson R. A. Philippi B." The Auk. 64 (1): 149–149. doi:10.2307/4080106. ISSN 0004-8038.

- ^ Nores, Manuel (2002-12-01). "Lista comentada de las aves argentinas". El Hornero. 17 (2): 113–114. doi:10.56178/eh.v17i2.881. ISSN 1850-4884.

- ^ a b c "Pteroptochos megapodius: BirdLife International". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012-05-01. Retrieved 2023-10-17.

- ^ Medrano, Fernando; Krabbe, Niels; Schulenberg, Thomas S.; Boesman, Peter F. D. (2021-05-07), "Moustached Turca (Pteroptochos megapodius)", Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, retrieved 2023-10-17

- ^ Muñoz-Sáez, Andrés; Perez-Quezada, Jorge F.; Estades, Cristián F. (2017). "Agricultural landscapes as habitat for birds in central Chile". Revista chilena de historia natural. 90. doi:10.1186/s40693-017-0067-0. ISSN 0716-078X.

- ^ Arévalo, Constanza; Amaya-Espinel, Juan David; Henríquez, Cristián; Ibarra, José Tomás; Bonacic, Cristián (2022-03-16). "Urban noise and surrounding city morphology influence green space occupancy by native birds in a Mediterranean-type South American metropolis". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 4471. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-08654-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8924563.

- ^ López-Jara, María José; Sacristán, Irene; Farías, Ariel A.; Maron-Perez, Francisca; Acuña, Francisca; Aguilar, Emilio; García, Sebastián; Contreras, Patricio; Silva-Rodríguez, Eduardo A.; Napolitano, Constanza (2021-07-01). "Free-roaming domestic cats near conservation areas in Chile: Spatial movements, human care and risks for wildlife". Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation. 19 (3): 387–398. doi:10.1016/j.pecon.2021.02.001. ISSN 2530-0644.