Jean Tarde

Jean Tarde | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1561 La Roque-Gageac |

| Died | 1636 La Roque-Gageac |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | University of Cahors, Sorbonne |

| Known for | Sunspots, Cartography |

Jean Tarde (b. La Roque-Gageac 1561 or 1562, d. La Roque-Gageac 1636) was Vicar general of Sarlat, famous for his chronicles of the diocese.[1] He was a Frenchman and was an early adopter of Copernican theory.[2] Tarde was born into a semi wealthy family in the bourgeois community in La Roque-Gageac, near Sarlat, France. He received his doctorate of law from the University of Cahors and then went on to the University of Paris to continue his studies.[3] Throughout his younger adult life, he held a number of different religious positions such as canon theologian, and almoner where during his free time he studied various sciences including mathematics, astronomy, physics, and geography.[1] He is most famous for his work with sunspots which he concluded were small satellites of the sun.

Biography

Jean Tarde belonged to an established family of Sarlat dating to a least the 14th century. The family had two branches, the du Ponts, to which Jean Tarde belonged, and the de Lisles. He studied at the university of Cahors and then at the Sorbonne, and was an expert in mathematical sciences.[4]

He became curate of Carves, near Belvès, before being appointed theological canon at the cathedral of Sarlat. He spent his leisure time on scientific studies, including mathematics, astronomy, physics and geography.

His love of antiquities prompted him to travel extensively, particularly in southeastern France, where he visited the main Gallo-Roman sites. He was at Béziers and Marseille in 1591, at resided in Nîmes and Uzès in 1592, 1593, and 1594. In 1593 he also visited Orange and Avignon, where he was given permission to pursue his research in the pontifical archives, from where he set off in his first visit to Rome, and to where he returned. On this first visit, in 1593, he spent his time with the great antiquarian Fulvio Orsini. It was also on this visit that he made the acquaintance of one of the finest mathematicians of the day, Christoph Clavius.[5]

During the Wars of Religion the archives of the cathedral were destroyed, and Tarde was in charge of reconstituting them. In 1594 the bishop of Sarlat also commissioned him to prepare a map of the diocese, illustrating the damage caused by the wars. To undertake this task, he walked the diocese with a quadrant, a compass needle and a sundial to establish distances and angles.[6] The chronicles he kept until 1630 probably date from this time as well. He also chronicled a journey to Rome that he undertook in 1593 on the bishop's instruction.

In March 1599, Henri IV named him almoner in ordinary.[7]

In 1629, Tarde was made a member of the Conseil du Roi, a hereditary position retained by his family until the French Revolution.

Jean Tarde considered sunspots to be tiny planets between Mercury and the sun. His religious beliefs prevented him from accepting that sunspots appeared on the Sun itself because the Sun was a sacred place chosen by God himself and it could not be corrupt. This theory was grounded in the biblical phrase "In sole posuit tabernaculum Suum" (‘[God] has pitched his tent in the sun’) which he referred to in his writing. The idea of the Sun being pure and sacred was based not only in the bible but in the philosophy of Aristotle.[2]

Astronomy

Discussions with Galileo Galilei

First learning of Galileo's work through Robert Balfour who knew him, Jean Tarde read Sidereus Nuncius and wanted to find out more. During his visit to Florence, Jean Tarde went to see Galileo in 1614, November 12. Tarde admired Galileo writing in his own diary after the encounter, "In the morning I went to see Master Galileo, famed philosopher and astronomer.... I told him that his fame had crossed the Alps, traversed France, and reached even to the ocean." In their conversation, he talked with Galileo about several topics such as the "moons" (ring) of Saturn and phases of Venus. Galileo believed that the spots traveled the same path as Venus and Mercury taking 14 days to cross the middle of the earth. Galileo also felt that there was no parallax for the spots, meaning the spots had to be very close to or on the sun, not the earth. He knew his claims may have been hard to believe, so Galileo also told Tarde that others had seen the same spots he had seen, which in effect helped validate his sightings.[2]

Later in their conversation, Tarde asks Galileo how to make a telescope. Galileo claimed to now know how the scope worked, but he did reference Tarde to Kepler's book on optics. Galileo was supposed to send Tarde better lenses while Tarde was in Rome, however months went by and he still had not (this was known by Tarde's letters to Galileo). However Tarde and Galileo encountered each other a few times after their conversation and Galileo revealed more and more about what he had discovered with the telescope.[2]

Jean Tarde wrote about his meeting and discussion with Galileo in his diary. However, the section of the interview in which he had discussed sunspots with Galileo was crossed out. The reasons Jean Tarde did this is unknown and are a subject of debate among historians. Some historians have suggested that Jean Tarde learned that Galileo was not the first to discover sunspots as he had claimed at the time. Galileo and Tarde met up a few times after this.[2]

Discussions with Christoph Grienberger

After meeting with Galileo in Florence, Jean Tarde went to back to Rome where he meet the Jesuit mathematician Christoph Grienberger. Jean Tarde learned several more things about sunspots from Christoph Grienberger. Among these Christoph Grienberger told Jean Tarde that numerous other astronomers in both Italy and Germany had been able to observe the sunspots. Christoph Grienberger explained that there were two main threads of thought about what sunspots were; he said that people either thought sunspots were small planets extremely close to the Sun or some sort of phenomena in the Sun's atmosphere. He also demonstrated four methods of observing sunspots to Jean Tarde.[2]

Research at Sarlat

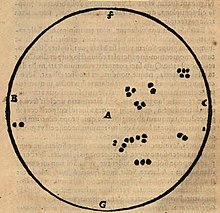

Jean Tarde returned to Sarlat in 1615 February and constructed a small observatory. It is unknown if the telescope he used the lens promised by Galileo. Jean Tarde made observations by casting a projection of the Sun onto a white sheet inside his darkened observatory. Using this method he took long and detailed logs of sunspots and their movements. These records would be used several years later when writing his book.[2]

In 1615 August 25 Jean Tarde observed over 30 sunspots on the face of the Sun at once.[2]

"The Bourbon Planets"

Jean Tarde started writing his book on sunspots in 1619. He eventually published two versions of the book on the topic: Borbonia Sidera in Latin in 1620 and Astras de Borbon in French in 1622. The titles of these books mean "Bourbon Stars", dedicated to Louis XIII and the ruling family of France; likely in order to try to gain patronage, like many other scientists of the time.[2]

In these books Tarde lays out his observations and arguments about the nature of the recently discovered sunspots. Tarde refutes the theory that the spots were on the Sun or in the Sun's atmosphere by claiming this "violates the Aristotelian principle that the heavens were not subject to corruption". The Peripatetics felt the claim was outrageous and offensive. Tarde says the spots are actually clouds and emissions from the Sun. Tarde argued that spots can not diminish the Sun because the Sun is the father of light. He states, "It is the seat of God, His house, His tabernacle. It is impious to attribute to God's house the filth, corruption and blemishes of the Earth." Tarde felt the Sun was a perfect sphere and was flawless.[2]

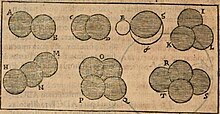

Instead, Tarde favored the view that sunspots were instead a series of small planets orbiting closely to the Sun. In his book he laid out a series of twenty properties of the sunspots which he believed lead to the conclusion that sunspots were planets. Among the properties he cited were:

- The number of sunspots and the frequency of their appearance were far to great to be transits of the other inner planets; Venus and Mercury. He even pointed out that an observation of Kepler's, "a little daub, quite black, approximately like a flea," which Kepler thought was a transit of Mercury was actually a sunspot. He made similar claims about observations by Julius Caesar Scaliger.

- He compared the darkness that the sunspots on the Sun were similar in darkness to that of the shadow of the Earth on the Moon during a lunar eclipse.

- Many people at the time held to the view that the seven planets known to the ancients; Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the Moon, and the Sun. Jean Tarde asserted that this belief was wrong by discussing how several ancient cultures believed in an infinite number of worlds. Although he didn't actually believe there was an infinite number of worlds he did cite the recent discoveries of the Jupiter's Galilean moons and Saturn's two moons (actually rings). He also cited the vast number of new stars visible now through telescopes.

- He asserted that sunspots could not be stars because were not luminous like other stars.

- He argued against Galileo's proof that sunspots were not planets because of their irregular shape using several claims. Including, that the brightness of the Sun made it impossible to get a clear picture of the sunspots' roundness, that current telescopes had issues with resolving dim and far away objects, and that the sunspots would be undergoing phases like the other inner planets.

- He argued that apparent motion across the ecliptic was caused by the angle of viewing of the observer standing on the Earth.

- Galileo had argued that sunspots must have to be on the Sun because they show no parallax. In response Tarde argued that they were either too close to the Sun to get an accurate measurement or that the change in parallax was so slight that it would have to have constant monitoring. Thus even one cloudy day would prevent its measurement.

- One large problem which Galileo had posed to Tarde was that the Venus' orbit was quicker than Earth's and Mercury's faster than Venus' so why didn't the sunspots go faster? In response, Tarde argued that the variable speeds of the sunspots was part of how they could be identified.

- He also thought that the Sun was incorruptible.

Through Tarde had many findings, it was not until years after he made discoveries that he published his work unlike the other philosophers of his time. Though Tarde had put so much time and effort into his work, the recognition he wished to have gained from the king was not presented to him. He even abandoned the sunspots theory for a couple of years where he then returned to the conversation in Dialogue on the two world systems of 1632. In later years, several philosophers began to discuss Tarde's work. Some agreed with Tarde, some disagreed, but the discussion was still happening. However, once Tarde died, so did the conversation about sunspots. In the following years, some sightings of sunspots were found in 1640 and the conversation began again.

Published works

- Chroniques de Jean Tarde

- Les usages du quadrant à l'esguille aymantée divisée en deux livres, 1621

- Borbonia sidera, id est Planetae qui solis limina circumvolitant motu proprio ac regulari, falso hactenus ab helioscopis maculae solis nuncupati. Ex novis observationibus Joannis Tarde, 1620

- Les Astres de Borbon et apologie pour le soleil, monstrant et vérifiant que les apparences qui se voyent dans la face du soleil sont des planètes, et non des taches, 1622

- Description du diocèse de Sarlat et Haut Périgord, 1624

- Le diocèse de Sarlat. Diocoesis Sarlatensis, 1625

- Potamographie de Garone et des fleuves qui se rendent dedans

- Description du pais de Quercy

References

- ^ a b Westfall, Richard. "Tarde, Jean". The Galileo Project. Rice University. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Baumgartner, F.J. (October 2018). ""Sunspots or Sun's Planets - Jean Tarde and the Sunspot Controversy of the Early 17TH-CENTURY"". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 18: 44–53. doi:10.1177/002182868701800103. S2CID 118641803 – via Harvard.edu.

- ^ Saridakis, Voula (October 2018). "Tarde, Jean". The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers – via Springer Link.

- ^ Henry Heller (9 May 2002). Labour, Science and Technology in France, 1500-1620. Cambridge University Press. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-0-521-89380-0.

- ^ Tronel, J.F. "Jean Tarde, un Savant Humaniste de Renom". Espritdepays.com. Esprit de Pays. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ John Michael Lewis (2006). Galileo in France: French Reactions to the Theories and Trial of Galileo. Peter Lang. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-8204-5768-0.

- ^ Recherches Sur Les Historiens Du Perigord. Slatkine. 1971. pp. 145–. GGKEY:ZZKAWCLLRXW.

Bibliography

- Gaston de Gérard, Gabriel Tarde, éditeur scientifique et préfacier de Les chroniques de Jean Tarde, p. VII-XLIV, H. Oudin, Paris, 1887 (lire en ligne)

- A. Dujarric-Descombes, Recherches sur les historiens du Périgord au XVIIe siècle - Tarde, p. 371-412, Bulletin de la Société historique et archéologique du Périgord, 1882, tome 9 (lire en ligne)

- Auguste Molinier, Les Chroniques de Jean Tarde..., par Gabriel Tarde, p. 117-119, Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes, 1888, nº 49

- Articles with hCards

- Articles with FAST identifiers

- Articles with ISNI identifiers

- Articles with VIAF identifiers

- Articles with WorldCat Entities identifiers

- Articles with BNE identifiers

- Articles with BNF identifiers

- Articles with BNFdata identifiers

- Articles with GND identifiers

- Articles with ICCU identifiers

- Articles with J9U identifiers

- Articles with KBR identifiers

- Articles with LCCN identifiers

- Articles with NLA identifiers

- Articles with NTA identifiers

- Articles with VcBA identifiers

- Articles with Trove identifiers

- Articles with SUDOC identifiers

- 1562 births

- 1636 deaths

- 16th-century French scientists

- People from Sarlat-la-Canéda

- 16th-century French historians

- 16th-century French male writers

- 17th-century French astronomers