History of Christianity in Norway

The history of Christianity in Norway started in the Viking Age in the 9th century. Trade, plundering raids, and travel brought the Norsemen into close contacts with Christian communities, but their conversion only started after powerful chieftains decided to receive baptism during their stay in England or Normandy. Haakon the Good was the first king to make efforts to convert the whole country, but the rebellious pagan chieftains forced him to apostatize. Olaf Tryggvason started the destruction of pagan cult sites in the late 10th century, but only Olaf Haraldsson achieved the official adaption of Christianity in the 1020s. Missionary bishops subjected to the archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen were responsible for the spread of the new faith before the earliest bishoprics were established around 1100.

Pagan beliefs

Manuscripts written in the 13th century preserved most information about the Norsemen's pre-Christian religious beliefs.[1] The Poetic Edda contain Old Norse poems about the creation and the end of the world.[1] Snorri Sturluson incorporated several myths of Odin, Thor, Týr, and other pagan gods in his Prose Edda.[2] Odin was the most important god of the pantheon, but he was never regarded omnipotent.[2] The gods were thought to live in farms together with their sposes and children, just like their mortal worshippers.[2] The Eddas also mentioned the jötnar (or giants), describing them as the gods' superhuman enemies.[2]

Old Norse religious practises are poorly documented.[3] The chieftains were allegedly the religious leaders of their communities, because the existence of a separate cast of priests cannot be detected.[4] Most cult sites, known as hofs, were large halls built on the chieftains' farms.[3] Gullgubber—small gold objects decorated with pagan motifs—placed near poles in early medieval buildings in Mære, Klepp, and other places are most frequently interpreted as a sign of a pagan cult center by archaeologists.[5] Christian laws also mentioned outdoor cult sites which were known as horgs.[6] Bans on eating horsemeat after the official conversion to Christianity imply that it was an important element of pagan cults.[3]

Norsemen buried their dead in the ground or cremated them, but they always placed burial gifts in the graves.[6] The wealth and social status of the deceased influenced the size of their graves and the amount of grave goods.[6] The highest-ranking chiefs and their relatives were buried under large burial mounds, but the poorest commoners' graves were almost invisible.[6]

The shamanistic belief system of the nomadic Saami, who lived in the northern regions, was different from the Old Norse religion.[6] The Saami mainly worshipped benevolent goddesses and buried their dead under piles of stones.[7] They were famed for their healing abilities for centuries, but their Christian neighbors often regarded them as wizards and sorcerers.[7]

Middle Ages

Towards conversion

Norsemen were brought into close contact with Christian communities in the Viking Age.[8] Reliquary, cross pendants and other objects of Christian provenance easily reached Norway through trade, plundering raids or travel from around 800.[9] Contemporaneous authors wrote of pagan Vikings who wore the sign of cross to mingle freely with the local crowd during their raids.[8] Christian objects were placed in the graves, especially in the graves of wealthy women, but their pagan context suggests that they rarely expressed the dead's adherence to Christianity.[10] A mould for a cross found at Kaupang—an important center of commerce in the 9th and 10th centuries—bears testimony to the local production of crosses, but it does not prove the existence of a local Christian community, because foreigners could also be the buyers of such products.[10]

The 13th-century Heimskringla attributes the conversion of Norway to four kings—Haakon the Good, Harald Greycloak, Olaf Tryggvason and Olaf Haraldsson—who were baptised abroad in the 10th and 11th centuries.[11] Earlier Christian missionaries are not mentioned in the primary sources.[8] The similar storylines of the four kings' biographies imply that their authors followed a common pattern, but most modern historians accept them as reliable sources.[11] The most ambitious chieftains could strengthen their personal links to foreign rulers through baptism.[12] Fights for the expansion of the new faith enabled the missionary kings to get rid of their enemies, replacing them with their own partisans.[13] The introduction of a professional cast of Christian priests abolished the religious leadership of the kings' heathen rivals.[13] The Christians' belief in one omnipotent God strengthened the ideological basis for a centralized monarchy.[13] Most commoners converted to Christianity either to demonstrate their loyalty to the Christian monarchs or to secure their support.[14]

Haakon the Good was the son of Harald Fairhair whom the sagas credited with the unification of Norway.[15] Harald sent Haakon to England to be brought up in King Æthelstan's court, most probably in token of an alliance between the two kings.[11][16] Haakon was baptised and Benedictine monks accompanied him back to his homeland around 934 to spread Christian ideas in his kingdom.[16][17] Sturluson claimed that Haakon also invited a bishop from England.[18] The bishop may have been identical with a monk from the Anglo-Saxon Glastonbury Abbey who was known as Sigefridus Norwegensis episcopus ("Sigefrid, bishop of the Norwegians").[18][19] The pagan chieftains of Møre and Trøndelag rebelled against Haakon, destroyed the churches that he had built and murdered the Christian missionaries.[11][16] They also forced the king to apostatize.[11] Archaeologists tentatively date a 10th-century churchyard at Veøy to Haakon's time.[16]

Harald Greycloak, who succeeded Haakon in 961, had been baptised in Northumbria.[11][16] He also tried to spread Christianity in Norway, but he was forced into exile.[11] The region of Oslo was directly subjected to the rule of Harald Bluetooth, King of Denmark, who had already converted to Christianity.[14] He sent two earls to the territory to force the local inhabitants to adopt Christianity.[14] Some of the 62 Christian graves excavated at St. Clement's Church in Oslo can be dated to Harald Bluetooth's rule.[14]

Olaf Tryggvason was a Viking warlord who had made plundering raids against the coasts of the Baltic Sea and England before being baptized in the early 990s.[16][11] The tribute that he collected in England enabled him to return to Norway in 995.[11] Adam of Bremen wrote that Tryggvason had been the "first to bring Christianity to Norway"; the monk Oddr Snorrason attributed the conversion of five countries—Iceland, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, Orkney, the Hebrides and Shetland—to Tryggvason's missionary campaigns.[20] A saga described him as a "horg breaker", referring to the destruction of pagan cult sites during his reign.[6]

Christianization

Olaf Haraldsson completed the missionary work that his three Christian predecessors had commenced.[21] He was baptized in Rouen in Normandy before he invaded Norway in 1015.[11] Anglo-Saxon clergymen accompanied him to the kingdom, according to the sagas.[22] Anglo-Saxon influence both on the Christian vocabulary of the Norwegian language and on the earliest Christian laws is well-documented.[23] Adam of Bremen claimed that Olaf had also urged the archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen to send German missionaries to Norway.[22]

Olaf convoked a thing (or general assembly) to Moster where the official conversion of Norway to Christianity was decided in 1022.[24] The king and Bishop Grimketel introduced the earliest Christian laws at the same assembly.[24] Historians have traditionally interpreted the runic inscription on the Kuli stone as a reference to the thing, but both the dating of the stone and the reading of the fragment ris..umr on it as kristintumr ("Christendom") are problematic.[21]

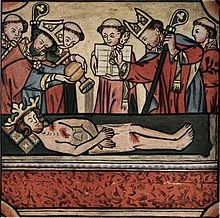

Cnut the Great, King of England and Denmark, and the Norwegian chieftains who supported him expelled Olaf from the country in 1028 or 1029.[25] According to Adam of Bremen, the chieftains rose up against Olaf because he had ordered their wives' execution for witchcraft, but Olaf's most enemies were actually Christians.[25] Cnut is credited with the establishment of a Benedictine monastery in Trondheim by an Anglo-Saxon source, but modern historians do not regard it a reliable source.[26] Olaf returned to Norway and died fighting against his enemies in the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030.[25][27] Sagas written in the early 1030s testify that Olaf was venerated as a holy king soon after his death.[25]

Court poets rarely referred to pagan myths in their poems written after Olaf's reign, which is a clear sign of the spread of Christian ideas.[27] Archeologically, the process of Christianization cannot be exactly documented, especially because Christian burials cannot be certainly identified and dated.[28] Pagan burials allegedly disappeared between 950 and 1050 in most regions, but the Saami insisted on their traditional faith for centuries.[29] Both written sources and archaeological finds evidence that the new faith spread from the coastlines to the inland regions.[19] The earliest Christian churches were most frequently built on previous heathen cemeteries, but the coexistence of Christian and pagan communities in the same settlements cannot be proved.[28]

Development of Church organization

The conversion to Christianity brought about the establishment of a hierarchically organized Church in Norway.[30] Only professional clerics could celebrate the Mass which was the central ceremony of Christianity.[30] The clerics also surveyed their parishioners' way of life, because medieval Christians were required to respect a series of rules governing their everyday life.[31] They could not work on ecclesiastical holiday and they had to fast on each Friday.[31]

The archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen were responsible for the missions in Scandinavia.[32] Olaf Haraldsson's half-brother, Harald Hardrada,[33] who was king of Norway from 1046 to 1066, preferred bishops ordained in England or France, but Pope Leo IX confirmed the jurisdiction of the German archbishops in Norway in 1053.[34] Missionary bishops were the first prelates in Norway, but they had no established sees.[35] Adam of Bremen recorded that the Norwegian dioceses had still no defined boundaries in 1076.[36][37] The fylki (or counties), which were important elements of secular administration, became also the basic units of ecclesiastic organization, most probably already during the reign of Olaf Haraldsson.[38] One church was recognized in each fylki as the district's principal church.[39] The fylki were divided into fourths or eighths and a church of minor rank was established in each subdivision.[39] Wealthy people were allowed to build private churches, known as convenience churches.[39] The earliest churches were built by the monarchs or noblemen and the builders' successors insisted on the appointment of the local priests.[40] Porches of the oldest stave churches were often decorated with scenes from pagan myths.[41] Most stone churches were built on the site of previous stave churches.[41] Anglo-Norman, German and Danish architecture influenced the design of the oldest churches, but a locally inspired style developed in Trondheim in the 11th century.[41]

The first permanent bishoprics—Bergen, Nidaros and Oslo—seems to have been founded during the reign of Harald Hardrada's successor, Olaf Kyrre, who died in 1093.[42] They were first listed in a document about the Scandinavian civitates (or bishoprics) shortly after 1100.[36] The document is most probably connected to the establishment of the Archbishopric of Lund in Denmark in 1104 by Pope Paschal II, which abolished the jurisdiction of the archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen in Scandinavia.[36][32] The large diocese of Bergen was divided into two when a new bishopric was set up at Stavanger around 1125.[43] A fifth diocese was established at Hamar through the division of the bishopric of Oslo in 1153 or 1154.[43]

Sigurd the Crusader ordered the collection of the tithe in 1096 or 1097.[41][44] The new tax which was regularly collected only from the middle of the 12th century enabled the organization of the first parishes.[44] Sigurd launched a crusade to the Holy Land in 1108.[45] He was the first king to strive for the establishment of an independent Norwegian archbishopric, but only the growing influence of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa in Denmark convinced the pope to support the idea.[46] In March 1152, Cardinal Nicholas Breakspear was appointed papal legate to Norway and Sweden and was tasked with the establishment of new archbishoprics.[46][47] Breakspear made Jon Birgersson the first archbishop of Nidaros in early 1153.[47] The archbishopric included all Norwegian dioceses and also six bishoprics in the oversea territories.[48] Breakspear also introduced the collection of the Peter's pence (an ecclesiastic tax payable to the Holy See) and organized the first cathedral chapters.[49][50] Most cathedral chapters consisted of 12 secular canons, each having their own prebend (or regular income).[50]

The first Benedictine monasteries were established around 1100.[26] Nidarholm Abbey was founded at Trondheim by a wealthy nobleman.[26] Munkeliv Abbey and Selje Abbey were established in the early 12th century.[26] The first Cistercian monks came from English abbeys in the 1140s.[17] Their earliest abbey was founded at Lyse near Bergen by the local bishop.[26] The first Augustinian community settled in Norway around 1150.[26] Premonstratensians also came to Norway in the middle of the 12th century, but they were not as popular as the Cistercians and Augustinians.[51]

The monarchs' correspondence with the popes show that they regarded themselves the actual rulers of the Norwegian church in the second half of the 11th century.[43] The establishment of the archbishopric at Nidaros strengthened the authority of the Holy See, especially because prelates who had been staunch supporters of the ideas of Gregorian Reform were made archbishops.[43][49] John Birgersson's successor, Eysteinn Erlendsson, crowned the minor Magnus Erlingsson king in 1163 or 1164.[52] Both the Law of Succession, which was issued before the ceremony, and the king's coronation oath emphasized that the monarchs should rule justly and seek advice from the prelates.[52] Archbishop Eysteinn also persuaded the king to confirm the privileges of the clergy around 1170.[52] The Gregorian ideas were actually not fully adopted.[52] Clerical celibacy, for instance, was not still a rule.[53] The Canones Nidrosienses—a collection of local canons—introduced a ban on marriage between a priest and a widow or a divorced woman, but otherwise ordinary priests were allowed to contract formal marriages.[53] Pope Gregory IX forbade the Norwegian priests to marry in 1237, but most of them continued to live with women and father children.[53] Concubinage could never be suppressed and priests' children were more easily acknowledged as legitimate heirs than in other parts of Catholic Europe.[53][54]

Sverre Sigurdsson who defeated and killed Magnus Erlingsson in 1184 refused to confirm the privileges of the Church.[55][56] He insisted on his right to appoint his candidates to the most important churches and to interfere in the election of bishops.[57] Archbishop Eysteinn and his successor, Eirik Ivarsson, were forced into exile.[57] Sverre crowned himself king in 1194[58] and refused to accept Pope Innocent III's judgement in favor of the exiled archbishop.[57] After all Norwegian bishops fled to Denmark to join their archbishop, the pope excommunicated the king.[57] The king's views were summarized in the Speech against the Bishops, which emphasized the monarchs' direct link to God.[59] Sverre's son, Haakon III, was reconciled with the Holy See.[57] The bishops' right to appoint the parish priests was confirmed, but the church builders' successors preserved the right to present their candidates to the bishops.[40] The expansion of the Nidaros Cathedral in Gothic style started in the 1180s and was completed in the 1210s.[26] The cathedral became the center of the cult of St Olaf.[26]

The mendicant orders settled in Scandinavia in the 1220s.[60] The Dominicans were the first to come, and the Franciscans soon followed them.[60] Haakon Haakonson, who mounted the throne in 1217, was the first king to make serious efforts to convert the Saami.[61] A Saami mystic convinced Margaret I to support new missions among the Saami in the 1380s, but the vast majority of the Saami remained pagans.[61]

References

- ^ a b Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 123.

- ^ a b c Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 124.

- ^ Bagge 2016, p. 64.

- ^ Bagge & Nordeide 2007, pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b c d e f Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 125.

- ^ a b Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 129.

- ^ Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 130.

- ^ a b Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Winroth 2012, p. 115.

- ^ Bagge 2016, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Bagge 2016, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 139.

- ^ Bagge 2016, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 135.

- ^ a b Orrman 2003, p. 440.

- ^ a b Sawyer & Sawyer 2010, p. 102.

- ^ a b Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 140.

- ^ Bagge & Nordeide 2007, pp. 136, 157.

- ^ a b Winroth 2012, p. 116.

- ^ a b Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 136.

- ^ Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 138.

- ^ a b Sawyer & Sawyer 2010, p. 215.

- ^ a b c d Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 137.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 151.

- ^ a b Sawyer & Sawyer 2010, p. 57.

- ^ a b Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 133.

- ^ Bagge & Nordeide 2007, pp. 133, 141.

- ^ a b Bagge 2016, p. 70.

- ^ a b Bagge 2016, p. 71.

- ^ a b Orrman 2003, p. 429.

- ^ Bagge 2016, p. 54.

- ^ Orrman 2003, pp. 428–429.

- ^ Winroth 2012, pp. 118–119.

- ^ a b c Sawyer & Sawyer 2010, p. 108.

- ^ Winroth 2012, p. 119.

- ^ Bagge & Nordeide 2007, pp. 128, 153.

- ^ a b c Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 153.

- ^ a b Orrman 2003, p. 450.

- ^ a b c d Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 154.

- ^ Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 150.

- ^ a b Orrman 2003, p. 434.

- ^ Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 157.

- ^ a b Orrman 2003, p. 430.

- ^ a b Sawyer & Sawyer 2010, p. 115.

- ^ Winroth 2012, pp. 119–120.

- ^ a b Orrman 2003, p. 431.

- ^ a b Sawyer & Sawyer 2010, p. 150.

- ^ Orrman 2003, p. 441.

- ^ a b c d Bagge 2016, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d Bagge 2016, p. 80.

- ^ Orrman 2003, p. 449.

- ^ Sawyer & Sawyer 2010, p. 63.

- ^ Bagge 2016, pp. 55, 81.

- ^ a b c d e Sawyer & Sawyer 2010, p. 117.

- ^ Sawyer & Sawyer 2010, p. 148.

- ^ Bagge & Nordeide 2007, p. 148.

- ^ a b Orrman 2003, p. 442.

- ^ a b Orrman 2003, p. 422.

Sources

- Bagge, Sverre; Nordeide, Sæbjørg Walaker (2007). "The kingdom of Norway". In Berend, Nora (ed.). Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus', c.900-1200. Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–166. ISBN 978-0-521-87616-2.

- Bagge, Sverre (2016). Cross and Scepter: The Rise of the Scandinavian Kingdoms from the Vikings to the Reformation. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16908-8.

- Orrman, Sverre (2003). "Church and society". In Helle, Knut (ed.). The Cambridge History of Scandinavia, Volume I: Prehistory to 1520. Cambridge University Press. pp. 421–464. ISBN 0-521-47299-7.

- Sawyer, Birgit; Sawyer, Peter (2010). Medieval Scandinavia: From Conversion to Reformation, circa 800–1500. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-1739-5.

- Winroth, Anders (2012). The Conversion of Scandinavia: Vikings, Merchants, and Missionaries in the Remaking of Northern Europe. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17026-9.