History of Australia (1851–1900)

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

The History of Australia (1851–1900) refers to the history of the indigenous and colonial peoples of the Australian continent during the 50-year period which preceded the foundation of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

Gold rushes and self-government

Although gold had been found in Australia as early as 1823 by surveyor James McBrien, a gold rush began when Edward Hargraves widely publicised his discovery of gold near Bathurst, New South Wales, in February 1851. Further discoveries were made later that year in Victoria, where the richest gold fields were found. By British law all minerals belonged to the Crown, and the governors of New South Wales and Victoria quickly introduced laws aimed at avoiding the disorder associated with the California gold rush of 1848. Both colonies introduced a gold mining licence with a monthly fee, the revenue being used to offset the cost of providing infrastructure, administration and policing of the gold fields. As the size of allowable claims was small (6.1 metres square), and much of the gold was near the surface, the licensing system favoured small prospectors over large enterprises.[1]

The gold rush initially caused some economic disruption including wage and price inflation and labour shortages as male workers moved to the goldfields. In 1852, the male population of South Australia fell by three per cent and that of Tasmania by 17 per cent. Immigrants from the United Kingdom, continental Europe, the United States and China also poured into Victoria and New South Wales. The Australian population increased from 430,000 in 1851 to 1,170,000 in 1861. Victoria became the most populous colony and Melbourne the largest city.[2][3]

Chinese migration was a particular concern for colonial officials. There were 20,000 Chinese miners on the Victorian goldfields by 1855 and 13,000 on the New South Wales diggings. There was a widespread belief that they represented a danger to white Australian living standards and morality, and colonial governments responded by imposing a range of taxes, charges and restrictions on Chinese migrants and residents. Anti-Chinese riots erupted on the Victorian goldfields in 1856 and in New South Wales in 1860.[4] According to Stuart Macintyre, "The goldfields were the migrant reception centres of the nineteenth century, the crucibles of nationalism and xenophobia[.]"[5]

The Eureka stockade

As more men moved to the goldfields and the quantity of easily-accessible gold diminished, the average income of miners fell. Victorian miners increasingly saw the flat monthly licence fee as a regressive tax and complained of official corruption, heavy-handed administration and the lack of voting rights for itinerant miners. Protests intensified in October 1854 when three miners were arrested following a riot at Ballarat. Protesters formed the Ballarat Reform League to support the arrested men and demanded manhood suffrage, reform of the mining licence and administration, and land reform to promote small farms. Further protests followed and protesters built a stockade on the Eureka Field at Ballarat. On 3 December troops overran the stockade, killing about 20 protesters. Five troops were killed and 12 seriously wounded.[6]

Following a Royal Commission, the monthly licence was replaced with an annual miner's right at a lower cost which also gave holders the right to vote and build a dwelling on the goldfields. The administration of the Victorian goldfields was also reformed. Stuart Macintyre states, "The Eureka rebellion was a formative event in the national mythology, the Southern Cross [on the Eureka flag] a symbol of freedom and independence."[7] However, according to A. G. L. Shaw, the Eureka affair "is often painted as a great fight for Australian liberty and the rights of the working man, but it was not that. Its leaders were themselves small capitalists...and even after universal suffrage was introduced...only about a fifth of the miners bothered to vote."[8]

Colonial self-government

Elections for the semi-representative Legislative Councils, held in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Van Diemen's Land in 1851, produced a greater number of liberal members. That year, the New South Wales Legislative Council petitioned the British Government requesting self-government for the colony. The Anti-Transportation League also saw the convict system as a barrier to the achievement of self-government. In 1852, the British Government announced that convict transportation to Van Diemen's Land would cease and invited the eastern colonies to draft constitutions enabling responsible self-government. The Secretary of State cited the social and economic transformation of the colonies following the discoveries of gold as one of the factors making self-government feasible.[9]

The constitutions for New South Wales, Victoria and Van Diemen's Land (renamed Tasmania in 1856) gained Royal Assent in 1855, that for South Australia in 1856. The constitutions varied, but each created a lower house elected on a broad male franchise and an upper house which was either appointed for life (New South Wales) or elected on a more restricted property franchise. Britain retained its right of veto over legislation regarding matters of imperial interest. When Queensland became a separate colony in 1859 it immediately became self-governing, adopting the constitution of New South Wales. Western Australia was granted self-government in 1890.[10]

Exploration of the interior

In 1860, Burke and Wills led the first south–north crossing of the continent from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Lacking bushcraft and unwilling to learn from the local Aboriginal people, Burke and Wills died in 1861, having returned from the Gulf to their rendezvous point at Coopers Creek only to discover the rest of their party had departed the location only a matter of hours previously. They became tragic heroes to the European settlers, their funeral attracting a crowd of more than 50,000 and their story inspiring numerous books, artworks, films and representations in popular culture.[11][12]

In 1862, John McDouall Stuart succeeded in traversing central Australia from south to north. His expedition mapped out the route which was later followed by the Australian Overland Telegraph Line.[13]

The completion of this telegraph line in 1872 was associated with further exploration of the Gibson Desert and the Nullarbor Plain. While exploring central Australia in 1872, Ernest Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from a location near Kings Canyon and called it Mount Olga.[14] The following year Willian Gosse observed Uluru and named it Ayers Rock, in honour of the Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers.[15] In 1879, Alexander Forrest trekked from the north coast of Western Australia to the overland telegraph, discovering land suitable for grazing in the Kimberley region.[13]

Impact on indigenous population

The spread of sheep and cattle grazing after 1850 brought further conflict with Aboriginal tribes more distant from the closely settled areas. Aboriginal casualty rates in conflicts increased as the colonists made greater use of mounted police, Native Police units, and newly developed revolvers and breech-loaded guns. Conflict was particularly intense in NSW in the 1840s and in Queensland from 1860 to 1880. In central Australia, it is estimated that 650 to 850 Aboriginal people, out of a population of 4,500, were killed by colonists from 1860 to 1895. In the Gulf Country of northern Australia five settlers and 300 Aboriginal people were killed before 1886.[16] The last recorded massacre of Aboriginal people by settlers was at Coniston in the Northern Territory in 1928 where at least 31 Aboriginal people were killed.[17]

Broome estimates the total death toll from settler-Aboriginal conflict between 1788 and 1928 as 1,700 settlers and 17–20,000 Aboriginal people. Reynolds has suggested a higher "guesstimate" of 3,000 settlers and up to 30,000 Aboriginals killed.[18] A project team at the University of Newcastle, Australia, has reached a preliminary estimate of 8,270 Aboriginal deaths in frontier massacres from 1788 to 1930.[19]

In New South Wales, 116 Aboriginal reserves were established between 1860 and 1894. Most reserves allowed Aboriginal people a degree of autonomy and freedom to enter and leave. In contrast, the Victorian Board for the Protection of Aborigines (created in 1869) had extensive power to regulate the employment, education and place of residence of Aboriginal Victorians, and closely managed the five reserves and missions established since self government in 1858. In 1886, the protection board gained the power to exclude "half caste" Aboriginal people from missions and stations. The Victorian legislation was the forerunner of the racial segregation policies of other Australian governments from the 1890s.[20] The Queensland Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act of 1897 allowed the government to place any Aboriginal person on a reserve against their will. They were also denied the right to vote or drink alcohol.[21]

In more densely settled areas, most Aboriginal people who had lost control of their land lived on reserves and missions, or on the fringes of cities and towns. In pastoral districts the British Waste Land Act of 1848 gave traditional landowners limited rights to live, hunt and gather food on Crown land under pastoral leases. Many Aboriginal groups camped on pastoral stations where Aboriginal men were often employed as shepherds and stockmen. These groups were able to retain a connection with their lands and maintain aspects of their traditional culture.[22]

Boom, depression and race

Land reform

In the 1860s New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia introduced Selection Acts intended to promote family farms and mixed farming and grazing. Legislation typically allowed individual "selectors" to select small parcels of unused crown land or leased pastoral land for purchase on credit.[23] The reforms initially had little impact on the concentration of land ownership as large landowners used loopholes in the laws to buy more land. However, refinements to the legislation, improvements in farming technology and the introduction of crops adapted to Australian conditions eventually led to the diversification of rural land use. The expansion of the railways from the 1860s allowed wheat to be cheaply transported in bulk, stimulating the development of a wheat belt from South Australia to Queensland.[24] Land under cultivation increased from 200,000 hectares to 2 million hectares from 1850 to 1890.[25]

Bushrangers

The period 1850 to 1880 saw a revival in bushranging. The first bushrangers had been escaped convicts or former convicts in the early years of British settlement who lived independently in the bush, often supporting themselves by criminal activity. The early association of the bush with freedom was the beginning of an enduring myth. The resurgence of bushranging from the 1850s drew on the grievances of the rural poor (several members of the Kelly gang, the most famous bushrangers, were the sons of impoverished small farmers). The exploits of Ned Kelly and his gang garnered considerable local community support and extensive national press coverage at the time. After Kelly's capture and execution for murder in 1880 his story inspired numerous works of art, literature and popular culture and continuing debate about the extent to which he was a rebel fighting social injustice and oppressive police, or a murderous criminal.[26]

Economic growth and race

From the 1850s to 1871 gold was Australia's largest export and allowed the colony to import a range of consumer and capital goods. More importantly, the increase in population in the decades following the gold rush stimulated demand for housing, consumer goods, services and urban infrastructure.[27] By the 1880s half the Australian population lived in towns, making Australia more urbanised than the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada.[28] Between 1870 and 1890 average income per person in Australia was more than 50 per cent higher than that of the United States, giving Australia one of the highest living standards in the world.[29]

The size of the government sector almost doubled from 10 per cent of national expenditure in 1850 to 19 per cent in 1890. Colonial governments spent heavily on infrastructure such as railways, ports, telegraph, schools and urban services. Much of the money for this infrastructure was borrowed on the London financial markets, but land-rich governments also sold land to finance expenditure and keep taxes low.[30][31]

In 1856, building workers in Sydney and Melbourne were the first in the world to win the eight hour working day. The 1880s saw trade unions grow and spread to lower skilled workers and also across colonial boundaries. By 1890 about 20 per cent of male workers belonged to a union, one of the highest rates in the world.[32][33]

Economic growth was accompanied by expansion into northern Australia. Gold was discovered in northern Queensland in the 1860s and 1870s, and in the Kimberley and Pilbara regions of Western Australia in the 1880s. Sheep and cattle runs spread to northern Queensland and on to the Gulf Country of the Northern Territory and the Kimberley region of Western Australia in the 1870s and 1880s. Sugar plantations also expanded in northern Queensland during the same period.[34][35]

The gold discoveries in northern Australia attracted a new wave of Chinese immigrants. The Queensland sugar cane industry also relied heavily on indentured South Sea Island workers, whose low wages and poor working conditions became a national controversy and led to government regulation of the industry. Additionally, a significant population of Japanese, Filipinos and Malays were working in pearling and fishing. In 1890, the population of northern Australia is estimated at 70,000 Europeans and 20,000 Asians and Pacific Islanders. Indigenous people probably outnumbered these groups, leaving white people a minority north of the Tropic of Capricorn.[35]

From the late 1870s trade unions, Anti-Chinese Leagues and other community groups campaigned against Chinese immigration and low-wage Chinese labour. Following intercolonial conferences on the issue in 1880–81 and 1888, colonial governments responded with a series of laws which progressively restricted Chinese immigration and citizenship rights.[36]

1890s depression

Falling wool prices and the collapse of a speculative property bubble in Melbourne heralded the end of the long boom. When British banks cut back lending to Australia, the heavily indebted Australian economy fell into economic depression. A number of major banks suspended business and the economy contracted by 20 per cent from 1891 to 1895. Unemployment rose to almost a third of the workforce. The depression was followed by the "Federation Drought" from 1895 to 1903.[37]

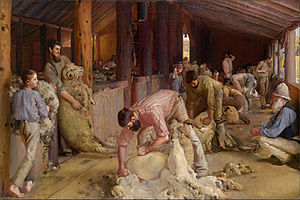

In 1890, a strike in the shipping industry spread to wharves, railways, mines and shearing sheds. Employers responded by locking out workers and employing non-union labour, and colonial governments intervened with police and troops. The strike failed, as did subsequent strikes of shearers in 1891 and 1894, and miners in 1892 and 1896. By 1896, the depression and employer resistance to trade unions saw union membership fall to only about five per cent of the workforce.[38]

The defeat of the 1890 Maritime Strike led trade unions to form political parties. In New South Wales, the Labor Electoral League won a quarter of seats in the elections of 1891 and held the balance of power between the Free Trade Party and the Protectionist Party. Labor parties also won seats in the South Australian and Queensland elections of 1893. The world's first Labor government was formed in Queensland in 1899, but it lasted only a week.[39]

From the mid-1890s colonial governments, often with Labor support, passed acts regulating wages, working conditions and "coloured" labour in a number of industries.[40]

At an Intercolonial Conference in 1896, the colonies agreed to extend restrictions on Chinese immigration to "all coloured races". Labor supported the Reid government of New South Wales in passing the Coloured Races Restriction and Regulation Act, a forerunner of the White Australia Policy. However, after Britain and Japan voiced objections to the legislation, New South Wales, Tasmania and Western Australia instead introduced European language tests to restrict "undesirable" immigrants.[41]

Democratic rights and restrictions

The secret ballot was adopted in Tasmania, Victoria and South Australia in 1856, followed by New South Wales (1858), Queensland (1859) and Western Australia (1877). South Australia introduced universal male suffrage for its lower house in 1856, followed by Victoria in 1857, New South Wales (1858), Queensland (1872), Western Australia (1893) and Tasmania (1900). Queensland excluded Aboriginal males from voting in 1885 (all women were also excluded). In Western Australia, a property qualification for voting existed for male Aboriginals, Asians, Africans and people of mixed descent.[42]

Propertied women in the colony of South Australia were granted the vote in local elections (but not parliamentary elections) in 1861. Henrietta Dugdale formed the first Australian women's suffrage society in Melbourne, Victoria in 1884.[43] Societies to promote women's suffrage were also formed in South Australia in 1888 and New South Wales in 1891. The Women's Christian Temperance Union established branches in most Australian colonies in the 1880s, promoting votes for women and a range of social causes.[44]

Women became eligible to vote for the Parliament of South Australia in 1895. This was the first legislation in the world permitting women also to stand for election to political office and, in 1897, Catherine Helen Spence became the first female political candidate for political office, unsuccessfully standing for election as a delegate to the Federal Convention on Australian Federation.[43][45] Women won the vote in Western Australia in 1899, with some restrictions based on race. Women in the remainder of Australia only won full rights to vote and to stand for elected office in the decade after Federation, although there were some racial restrictions.[46][47]

Indigenous Australian males gained the right to vote when Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania and South Australia gave voting rights to all male British subjects over 21. However, they were not encouraged to vote and few did. Only Queensland legally barred Aboriginal people from voting, although Western Australia had a property qualification which effectively denied them the vote.[42]

Nationalism and federation

Growth of nationalism

By the late 1880s, a majority of people living in the Australian colonies were native born, although more than 90 per cent were of British and Irish heritage.[48] The Australian Natives Association, a friendly society open to Australian-born males, flourished in the 1880s. It campaigned for an Australian federation within the British Empire, promoted Australian literature and history, and successfully lobbied for the 26 January to be Australia's national day.[49]

Australian nationalists often claimed that unification of the colonies was Australia's destiny. Australians lived on a single continent, and the vast majority shared a British heritage and spoke English. Many nationalists spoke of Australians sharing common blood as members of the British "race".[50] Henry Parkes stated in 1890, "The crimson thread of kinship runs through us all...we must unite as one great Australian people."[51]

A minority of nationalists saw a distinctive Australian identity rather than shared "Britishness" as the basis for a unified Australia. Some, such as the radical magazine The Bulletin and the Tasmanian Attorney-General Andrew Inglis Clark, were republicans, while others were prepared to accept a fully independent country of Australia with only a ceremonial role for the British monarch. In 1887, poet Henry Lawson wrote of a choice between "The Old Dead Tree and the Young Tree Green/ The Land that belongs to the lord and the Queen,/And the land that belongs to you."[52]

A unified Australia was usually associated with a white Australia. In 1887, The Bulletin declared that all white men who left the religious and class divisions of the old world behind were Australians.[53] The 1880s and 1890s saw a proliferation of books and articles depicting Australia as a sparsely populated white nation threatened by populous Asian neighbours.[54] A white Australia also meant the exclusion of cheap Asian labour, an idea strongly promoted by the labour movement.[55] According to historian John Hirst, "Federation was not needed to make the White Australia policy, but that policy was the most popular expression of the national ideal that inspired federation."[56]

Federation movement

Growing nationalist sentiment coincided with business concerns about the economic inefficiency of customs barriers between the colonies, the duplication of services by colonial governments and the lack of a single national market for goods and services.[57] Colonial concerns about German and French ambitions in the region also led to British pressure for a federated Australian defence force and a unified, single-gauge railway network for defence purposes.[58]

A Federal Council of Australasia was formed in 1885 but it had few powers and New South Wales and South Australia declined to join.[59]

An obstacle to federation was the fear of the smaller colonies that they would be dominated by New South Wales and Victoria. Queensland, in particular, although generally favouring a white Australia policy, wished to maintain an exception for South Sea Islander workers in the sugar cane industry.[60]

Another major barrier was the free trade policies of New South Wales which conflicted with the protectionist policies dominant in Victoria and most of the other colonies. Nevertheless, the NSW premier Henry Parkes was a strong advocate of federation and his Tenterfield Oration in 1889 was pivotal in gathering support for the cause. Parkes also struck a deal with Edmund Barton, leader of the NSW Protectionist Party, whereby they would work together for federation and leave the question of a protective tariff for a future Australian government to decide.[61]

In 1890, representatives of the six colonies and New Zealand met in Melbourne and agreed in principle to a federation of the colonies and for the colonial legislatures to nominate representatives to attend a constitutional convention. The following year, the National Australasian Convention was held in Sydney, with all the future states and New Zealand represented. A draft constitutional Bill was adopted and transmitted to the colonial parliaments for approval by the people. The worsening economic depression and parliamentary opposition, however, delayed progress.[62]

In early 1893 the first citizens' Federation League was established in the Riverina region of New South Wales and many other leagues were soon formed in the colonies. The leagues organised a conference in Corowa in July 1893 which developed a new plan for federation involving a constitutional convention with directly elected delegates and a referendum in each colony to endorse the proposed constitution. The new NSW premier, George Reid, endorsed the "Corowa plan" and in 1895 convinced the majority of other premiers to adopt it.[63]

Most of the colonies sent directly elected representatives to the constitutional convention, although those of Western Australia were chosen by its parliament. Queensland did not send delegates. The convention held sessions in 1897 and 1898 which resulted in a proposed constitution for a Commonwealth of federated states under the British Crown.[64]

Referendums held in 1898 resulted in solid majorities for the constitution in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. However, the referendum failed to gain the required majority in New South Wales after that colony's Labor Party campaigned against it and premier Reid gave it such qualified support that he earned the nickname "yes-no Reid".[65]

The premiers of the other colonies agreed to a number of concessions to New South Wales (particularly that the future Commonwealth capital would be located in that state), and in 1899 further referendums were held in all the colonies except Western Australia. All resulted in yes votes.[66]

In March 1900, delegates were dispatched to London, including Barton and the Victorian parliamentarian Alfred Deakin, who had been a leading advocate for federation. Following intense negotiations with the British government, the federation Bill was passed by the imperial parliament on 5 July 1900 and gained Royal Assent on 9 July. Western Australia subsequently voted to join the new federation.[67]

Religion, education and culture

Religion

There was no established church in the colonies and the major churches were largely divided along ethnic lines, the Church of England's adherents being mostly of English heritage, Presbyterians mostly Scottish and Catholics mostly Irish. The decades from the gold rushes brought an increase in population and religion.[68] Church attendance among Anglicans and Presbyterians doubled in the 1860s, but growth of Catholicism and Methodism was even higher. Chinese religions and Christian sects also gained a foothold. Nevertheless, some 30 to 40% of the population did not regularly attend church by 1871. Missionary organisations such as the Bush Missionary Society and the Bible Christian Bush Mission attempted to combat this. City missions were also established.[69]

Missionary work also extended to Aboriginal people. Six missions in Victoria were established by 1860. A Methodist school and a Benedictine mission had been opened in Western Australia by 1846. The Anglican Pooninde Mission opened in South Australia in 1850 and the Maloga Mission was opened in New South Wales in 1874. The Mapoon mission (established 1891) and Yarrabah mission (established 1893) were two of the most enduring in Queensland.[70]

Religious groups were prominent in health, education and welfare.[68] The Sisters of Charity opened St Vincent's Hospital in Sydney in 1857. In 1867 Mary McKillop founded the Sisters of St Joseph to teach children in rural areas. Irish immigration to Australia increased in the 1860s, and sectarian differences between Protestants and Catholics increased. Between 1872 and 1896 all colonial governments withdrew state funding of religious schools, and the Catholic church responded by expanding its school system as an alternative to secular education.[71] In the later part of the century, the Catholic church also became closely associated with Australian nationalism.[72]

Christian revivalism became prominent in the 1870s. The Salvation Army commenced in 1880 and Catholic parish missions such as the Redemptorists, Vincentians and Passionists were established. Christian women's groups such as The Protestant Woman's Christian Temperance Union and the Anglican Mother's Union were also formed. Nevertheless, there was steady growth in secular views and although 96% of the Australian population identified as Christian in 1901, less than half attended church regularly.[73]

Education

In the 1850s, most schooling was conducted by religious organisations. The Catholic church ran colleges and convent schools in the major settlements and country areas which catered for both Catholics and Protestants. Protestant schools mainly catered for pupils from affluent backgrounds and emphasised preparation for the professions. In 1861, however, only half of school age children were literate and colonial governments became more committed to universal secular education.[74]

In 1866, New South Wales created a council to oversee public and religious schools in the colony, and public schools were progressively established in localities with 25 or more pupils. In 1872, Victoria was the first colony to legislate for the progressive introduction of free, compulsory and secular schools. As similar acts were passed in other colonies, state funding was withdrawn from religious schools. In response, the Catholic church expanded its own network of schools, leading to a division between state and Catholic schools.[75]

Although most children attended primary education, secondary education was sporadic. New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia established secondary schools called "superior," "high," or "grammar" schools, whereas Victoria and Tasmania offered scholarships to private schools and colleges.[76]

The first Australian universities were The University of Sydney (1850), the University of Melbourne (1853), the University of Adelaide (1874) and the University of Tasmania (1890). These were secular and selected students on academic merit based on examinations. Adelaide accepted female students from 1876, Melbourne from 1880, Sydney from 1882 and Tasmania from 1893.[77]

Technical education in mining, agriculture and other vocational areas was provided in several colonies by the 1870s and 1880s. prominent institutions included the Ballarat School of Mines in Victoria (founded 1870) and the Roseworthy Agricultural College in South Australia (founded 1883). Adult education in literacy, numeracy, the liberal arts and technical subjects was also provided by mechanics' institutes and schools of arts which were established in most cities and large towns.[78][79]

Culture

Magazines and newspapers continued to be the major means of publication of Australian novels and poetry. Marcus Clarke's For the Term of His Natural Life was serialised in 1870-72 before being published as a book in Melbourne and London a few years later. Rolf Boldrewood's Robbery Under Arms was serialised in 1882-83 before book publication in 1888.[80] Charles Harpur, Henry Kendall and Adam Lindsay Gordon were prominent in attempts to establish a "national poetry" from the 1860s.[81][82]

The growing nationalist sentiment in the 1880s and 1890s was associated with the development of a distinctively Australian art and literature. Artists of the Heidelberg School such as Arthur Streeton, Frederick McCubbin and Tom Roberts followed the example of the European Impressionists by painting in the open air. They applied themselves to capturing the light and colour of the Australian landscape and exploring the distinctive and the universal in the "mixed life of the city and the characteristic life of the station and the bush".[83]

In the 1890s Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson and other writers associated with The Bulletin produced poetry and prose exploring the nature of bush life and themes of independence, stoicism, masculine labour, egalitarianism, anti-authoritarianism and mateship. Protagonists were often shearers, boundary riders and itinerant bush workers. In the following decade Lawson, Paterson and other writers such as Steele Rudd, Miles Franklin, and Joseph Furphy helped forge a distinctive national literature. Paterson's ballad "The Man from Snowy River" (1890) achieved popularity, and his lyrics to the song "Waltzing Matilda" (c. 1895) helped make it the unofficial national anthem for many Australians.[84]

Commercial theatre was the leading form of popular entertainment but was dominated by English and American plays. From the 1870s, however, Australian plays became more frequent. Walter Cooper's spectacular melodrama Sun and Shadow (1870), and adaptations of For the Term of His Natural Life and Robbery Under Arms were successful.[85][86]

Popular songs and ballads with Australian themes were common in the period and can mostly be traced back to English and Irish traditional music. American popular and traditional music was also disseminated between the Californian and Australian gold fields of the 1850s. Bush ballads and songs about bushrangers such as The Dying Stockman, The Old Bark Hut and The Wild Colonial Boy were popular.[87][88]

The gold rushes and subsequent strong population growth led to the development of a middle class which fostered a musical culture. Formal training in European music and audiences for operas, concerts and recitals grew.[89] Opera singer Nellie Melba (1861–1931) travelled to Europe in 1886 to commence her international career. She became an international success in her profession from the late 1880s.[90]

Sport

Spectator sports flourished over this period. Intercolonial cricket in Australia started in 1851 and the first cricket "Test Match" between Australia and England took place in Melbourne in 1877.[91][92] Australian Rules Football began in 1858,[92] and the first metropolitan Rugby Union competition was organised in 1874. Boxing and horse racing were popular. By the 1880s, the Melbourne Cup drew crowds of around 100,000. However, the first modern Olympics at Athens in 1896 attracted only one Australian competitor.[93][92]

See also

- Australia and the American Civil War

- History of Australia (1901–1945)

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

References

- ^ Goodman 2013, pp. 170–176

- ^ Macintyre 2020, pp. 95–96

- ^ Goodman 2013, pp. 180–81

- ^ Goodman 2013, pp. 182–84

- ^ Macintyre 2020, p. 99

- ^ Goodman 2013, pp. 177–78

- ^ Macintyre 2020, p. 97

- ^ Shaw, A. G. L. (1983). pp. 126–27

- ^ Curthoys & Mitchell 2013, pp. 159–60

- ^ Curthoys & Mitchell 2013, pp. 160–65, 168

- ^ Macintyre 2020, pp. 109–10

- ^ McDonald 2008, pp. 271–80

- ^ a b Macintyre 2020, p. 110

- ^ Green, Louis (1972). "Giles, Ernest (1835–1897)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Gosse, Fayette (1972). "Gosse, William Christie (1842–1881)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Flood 2019, pp. 125–30, 138

- ^ Broome 2019, p. 202

- ^ Broome 2019, pp. 54–55

- ^ Ryan, L. (2020). Digital map of colonial frontier massacres in Australia 1788–1930. Teaching History, 54(3), p. 18

- ^ Banivanua Mar & Edmonds 2013, pp. 355–58, 363–64

- ^ Broome 2019, pp. 118–20

- ^ Banivanua Mar & Edmonds 2013, pp. 355–60

- ^ Frost 2013, pp. 327–28

- ^ Hirst 2014, pp. 74–77

- ^ Macintyre, Stuart (2020). p. 108

- ^ Macintyre 2020, pp. 47, 107–08

- ^ Goodman 2013, pp. 180–81

- ^ Macintyre 2020, p. 118

- ^ Frost 2013, p. 318

- ^ Hirst 2014, pp. 79–81

- ^ Macintyre 2020, p. 103

- ^ Hirst 2014, pp. 82–86

- ^ Macintyre 2020, p. 134

- ^ Goodman 2013, p. 187

- ^ a b Macintyre, Stuart; Scalmer, Sean (2013). "Colonial states and civil society". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I. pp. 213–16.

- ^ Willard, Myra (1967). History of the White Australia Policy to 1920. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. pp. 56–94.

- ^ Macintyre 2020, pp. 138–39

- ^ Macintyre 2020, pp. 131–34

- ^ Bellanta 2013, pp. 229–30

- ^ Bellanta 2013, p. 231

- ^ Willard, Myra (1967). pp. 109–17

- ^ a b Curthoys & Mitchell 2013, pp. 160–65, 168

- ^ a b "Documenting Democracy". Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ Bellanta 2013, pp. 233–34

- ^ Museum of Australian Democracy, Old Parliament House. "Constitution (Female Suffrage) Act 1895 (SA)". Documenting a Democracy. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Hirst 2014, p. 58

- ^ Bellanta 2013, p. 220

- ^ D.M. Gibb (1982) National Identity and Consciousness. p. 33. Thomas Nelson, Melbourne. ISBN 0-17-006053-5

- ^ Hirst 2000, pp. 38–39

- ^ Hirst 2000, p. 16

- ^ Parkes, Henry (1890). The federal government of Australasia : speeches delivered on various occasions (November, 1889 – May, 1890). Sydney: Turner and Henderson. pp. 71–76.

- ^ Hirst 2000, pp. 11–13, 69–71, 76

- ^ Russell 2013, pp. 479–80

- ^ Lake 2013, pp. 539–43

- ^ Irving 2013, p. 248

- ^ Hirst 2000, p. 22

- ^ Hirst 2000, pp. 45–61

- ^ Irving 2013, p. 252

- ^ Irving 2013, pp. 250–51

- ^ Hirst 2000, pp. 107, 171–73, 204–11

- ^ Irving 2013, pp. 249–51

- ^ Irving 2013, pp. 252–55

- ^ Irving 2013, pp. 255–59

- ^ Irving 2013, pp. 259–61

- ^ Irving 2013, p. 262

- ^ Irving 2013, p. 263

- ^ Irving 2013, pp. 263–65

- ^ a b Macintyre 2020, pp. 123–25

- ^ O'Brien 2013, pp. 425–28

- ^ O'Brien 2013, pp. 432–33, 436

- ^ O'Brien 2013, pp. 430–31

- ^ Macintyre 2020, p. 125

- ^ O'Brien 2013, pp. 434, 436

- ^ Macintyre 2020, pp. 125–26

- ^ Horne & Sherington 2013, pp. 380–82

- ^ Horne & Sherington 2013, p. 383

- ^ Horne & Sherington 2013, pp. 377–78, 387

- ^ Dixon & Hoorn 2013, p. 497

- ^ Horn & Sherington 2013, pp. 375–76

- ^ Dixon & Hoorn 2013, p. 504

- ^ Dixon & Hoorn 2013, p. 491

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 85–87

- ^ Dixon & Hoorn 2013, pp. 500, 508

- ^ Macintyre 2020, pp. 140–41

- ^ Dixon & Hoorn 2013, pp. 504–05

- ^ Brisbane 1991, pp. 77, 87

- ^ Dixon & Hoorn 2013, pp. 501–02

- ^ Covell 2016, pp. 39–56

- ^ Covell 2016, pp. 17–25

- ^ "Melba, Dame Nellie (1861–1931)". Melba, Dame Nellie (1861 - 1931) Biographical Entry - Australian Dictionary of Biography Online. Adb.online.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 14 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Pollard, Jack (1986). The Pictorial History of Australian Cricket (revised ed.). Boronia: J.M Dent Pty Ltd & Australian Broadcasting Corporation. ISBN 0-86770-043-2.

- ^ a b c Macintyre 2020, p. 127

- ^ Bellanta 2013, p. 239

Sources

- Banivanua Mar, Tracey; Edmonds, Penelope (2013). "Indigenous and settler relations". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart, eds. (2013). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01153-3.

- Bellanta, Melissa (2013). "Rethinking the 1890s". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Brisbane, Katharine (1991). Entertaining Australia: an illustrated history. Sydney: Currency Press. ISBN 0868192864.

- Broome, Richard (2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788 (5th ed.). Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781760528218.

- Covell, Roger (2016). Australia's Music: Themes of a New Society (2nd ed.). Lyrebird Press. ISBN 9780734037824.

- Curthoys, Ann; Mitchell, Jessie (2013). "The advent of self-government". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Dalziell, Tanya (2009). "No place for a book? Fiction in Australia to 1890". In Pierce, Peter (ed.). The Cambridge History of Australian Literature. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521881654.

- Dixon, Robert; Hoorn, Jeanette (2013). "Art and literature: a cosmopolitan culture". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Flood, Josephine (2019). The Original Australians: the Story of the Aboriginal People (2nd ed.). Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781760527075.

- Frost, Lionel (2013). "The economy". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Gascoigne, John; Maroske, Sara (2013). "Science and technology". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Goodman, David (2013). "The gold rushes of the 1850s". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Hirst, John (2000). The Sentimental Nation: the making of the Australian Commonwealth. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195506200.

- Hirst, John (2014). Australian History in 7 Questions. Melbourne: Black Inc. ISBN 9781863956703.

- Horne, Julia; Sherrington, Geoffrey (2013). "Education". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Irving, Helen (2013). "Making the federal Commonwealth, 1890-1901". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Lake, Marilyn (2013). "Colonial Australia and the Asia-Pacific region". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Macintyre, Stuart (2020). A Concise History of Australia (5th ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108728485.

- McCalman, Janet; Kippen, Rebecca (2013). "Population and health". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- McDonald, John (2008). Art of Australia: Vol 1. Exploration to Federation. Sydney: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 9781405038690.

- O'Brien, Anne (2013). "Religion". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Russell, Penny (2013). "Gender and colonial society". In Bashford, Alison; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- Smith, Vivian (2009). "Australian colonial poetry, 1788-1888: Claiming the future, restoring the past". In Pierce, Peter (ed.). The Cambridge History of Australian Literature. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521881654.

- Webby, Elizabeth (2009). "The beginnings of literature in colonial Australia". In Pierce, Peter (ed.). The Cambridge History of Australian Literature. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521881654.

Further reading

- Clark, Victor S. "Australian Economic Problems. I. The Railways," Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 22, No. 3 (May, 1908), pp. 399–451 in JSTOR, history to 1907

- Arthur Patchett Martin (1889). "Australian Democracy". Australia and the Empire: 77–114. Wikidata Q107340686.

- Arthur Patchett Martin (1889). "Native Australians and Imperial Federation". Australia and the Empire: 189–231. Wikidata Q107340730.

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use dmy dates from November 2020

- Use Australian English from May 2017

- All Wikipedia articles written in Australian English

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- History of Australia (1851–1900)

- 19th century in Australia