Georges Blun

Georges Blun | |

|---|---|

Georges Blun, in the middle of the back row | |

| Born | 1 June 1893 |

| Died | 1999 |

| Nationality | French |

| Citizenship | French |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, Spy |

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service branch | Red Three |

| Codename | Long |

| Operations | Red Orchestra |

Georges Blun (1 June 1893 – 1999)[1] was a French journalist and intelligence agent who was the Berlin correspondent of the Journal de Paris.[2][3]

Early life, World War I and the interwar years

Georges Blun was born to a French family on 1 June 1893 in the then German-held region of Alsace-Lorraine. He was married to a fellow journalist. He worked for the British MI5, as well as French intelligence during World War I. In 1920 he was expelled from Switzerland for conducting "clandestine activities" and communist agitation. By 1925, he had grown close to the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[4][5][6]

From 1925 to 1930 he worked in the Weimar Republic as a correspondent for various newspapers, such as Journal des débats.[4]

In 1928, it was reported that following publication of a controversial ('distorted') article on the Silvesternacht (New Year's Eve) in Berlin in a Paris paper, he resigned his chairmanship of the Association of Foreign Press and made an apology visit to the government press department.[citation needed]

He returned to Switzerland in 1939 after having worked as a journalist in Berlin for a considerable amount of time.[6]

World War II

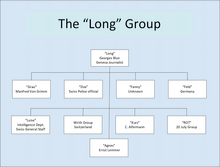

During World War II, he became a resistance fighter against Nazi Germany in the service of the Red Orchestra. Under the pseudonym "Long" he was the head of the eponymous George Blun group in Switzerland. This group formed part of the Red Three, led by Alexander Radó.[7][8]

During the war, he spied primarily and most notably in service of the Soviet Union, but also worked for American,[6] British, French, Swiss and Polish intelligence agencies as well – a fact described by at least one source covering the events as "common" among Switzerland-based spies at the time.[4] His loyalties were described by Nigel West as "always prioritizing" the Communist International and the GRU,[3] while the CIA assesses his group as having an "ambiguous" ideology.[7]

During his clandestine activities, he worked with figures such as Hans Bernd Gisevius, members of the 20 July plot, as well as Joseph Wirth (who had served as Chancellor of Germany).[7][9][4]

Blun's group was viewed by the Soviets as the second most valuable, after the group led by Rachel Dübendorfer.[7]

Post-War life

Blun survived the war, following which, along with Otto John and several others, he reportedly became a member of a political group led by Josef Müller. The group advocated for a united and neutralist Germany with a pro-USSR alignment.[7]

He was still working as a journalist on 11 May 1950, when he penned an article in the French Le Monde newspaper regarding the division of Berlin[10] and was cited for his work covering the division of the country.[11]

He died in 1999.[1]

Publications

- L'Allemagne mise a nu (La nouvelle Soc. d'Edition, Paris,. 1927, 183 p.) The Observer described it as being about "the German attitude toward foreign politics."[12] Foreign Affairs stated it was, "Germany as seen by the Berlin correspondent of the Paris Journal."[2]

References

- ^ a b "ISNI 0000000358781199 Blun, Georges (born 1893-06-01 deceased 1999)". www.isni.org. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ a b Langer, William L. "Some Recent Books on International Relations." Foreign Affairs, vol. 7, no. 1, 1928, pp. 156–167. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20028674. Accessed 10 February 2020.

- ^ a b West, Nigel (2008). Historical Dictionary of World War II Intelligence. Scarecrow Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780810858220. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d Kuznetsov, Viktor Vasilevich (2008). НКВД против гестапо [NKVD vs. the Gestapo] (in Russian). ISBN 978-5-6993-1250-4. Retrieved 14 February 2020 – via www.e-reading.life.

- ^ Prokhorov, Dmitry (2005). Сколько стоит продать Родину [How Much Does it Cost to Sell the Motherland] (in Russian). ОЛМА Медиа Групп. ISBN 978-5-7654-4469-6.

- ^ a b c West, Nigel (12 November 2007). Historical Dictionary of World War II Intelligence. Scarecrow Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8108-6421-4 – via books.google.com.

- ^ a b c d e Tittenhofer, Mark A. "The Rote Drei: Getting Behind the 'Lucy' Myth". CIA Library. Center for the Study of Intelligence. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ The Ultimate Spy Book (Dorling Kindersley Ltd., London), The world of intelligence, H. Keith Melton, Oleg Kalugin, and William Colby ISBN 9780241189917; Section: "The Red Orchestra“ … George Blun Group.

- ^ Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936–1945. Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 389. ISBN 0-89093-203-4.

- ^ Blun, Georges (11 May 1950). "Les alliés n'envisagent pas de discuter LA RÉPONSE SOVIÉTIQUE sur les élections quadriparties à Berlin" [The Allies do not plan to discuss SOVIET RESPONSE to four-party elections in Berlin]. Le Monde.fr (in French). Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ "Dans Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains" [In World Wars and Contemporary Conflicts]. Cairn. 12 January 2008. doi:10.3917/gmcc.210.0003. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Books and Authors". The Observer. 20 May 1928.

- CS1 uses Russian-language script (ru)

- CS1 Russian-language sources (ru)

- CS1 French-language sources (fr)

- Use dmy dates from December 2020

- Articles with hCards

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2021

- Articles with ISNI identifiers

- Articles with VIAF identifiers

- Articles with BIBSYS identifiers

- Articles with BNF identifiers

- Articles with BNFdata identifiers

- Articles with NLG identifiers

- Articles with SUDOC identifiers

- 1893 births

- 1999 deaths

- French centenarians

- French spies

- Soviet spies

- British spies

- World War II spies for the United States

- Polish spies

- World War I spies

- Interwar-period spies

- World War II spies

- 20th-century French journalists

- French Resistance members

- Red Orchestra (espionage)

- Date of death missing

- Place of death missing