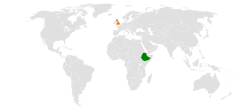

Ethiopia–United Kingdom relations

| |

Ethiopia |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Ethiopia, London | N/A |

| Envoy | |

| Kirsten Hillman | List of ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Ethiopia Alastair McPhail |

Ethiopia–United Kingdom relations are the bilateral relations between Ethiopia and the United Kingdom. Currently, Ethiopia has an embassy in London and United Kingdom has an embassy in Addis Ababa. Historically, their relations traced over centuries covered a range of areas including, but not limited to, trade, culture, education and development cooperation. The UK is the first country to open its embassy in Addis Ababa. Ethiopia is the first African country to open an embassy in London.

Overview

Both countries collaborated on issues, particularly in regional level such as in the Horn of Africa. For example, both are mutually working to ensure peace and stability in Somalia. At global level, they closely collaborated from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to combat climate change and terrorism. Their government actively participated in various global fora dealing these issues, particularly cooperation at the G8 and G20, a win-win example of developed and developing country.[1]

On bilateral level, their relations effectively grown over last decade[when?] and half. A steadfast cooperation, which the UK spend 0.7 of GDP to aid Ethiopia, remains one of the most dependable partnership between the two countries to fight against poverty. On the total amount, Ethiopia receives 80% of social service provision (such as education and healthcare services) and other direct involvement. The UK government assures their cooperation must bring transformation in the lives of beneficiaries. They use "value of money" standard to determine whether the relations between aid to recipient countries and outcome registered. For example, as Ethiopia paying dividend, the UK government continues development work with its government in expansion of industrialization through tough trade, investment and job creation.[1]

History

Zemene Mesafint

Formal relations established under Emperor Sahle Dengel in 1841 and the British consulate appointed at Massawa in 1842.[2]

Tewodros II

The British established one of foremost ties to the Ethiopian Empire under Tewodros II reign since its reunification after the Zemene Mesafint. By October 1862, Tewodros reign was marred by rebellion from Muslim Turks and Egyptian encroachments, as well as Sudanese and Muslim Oromo expansion in central Ethiopia. Tewodros wrote a letter to Queen Victoria as a fellow monarch to assist. Tewodros requested the British council in Ethiopia, Capitan Charles Dunan Cameron to supply firearms and bear technically skilled armies. However, as Cameron way to Ethiopia to deliver the letter, he informed to Foreign Office of the letter, which deprived to London rather for Tewodros. Through Sudan, Cameron returned Ethiopia; Tewodros enraged when he noticed he didn't deliver to the Queen personally. The Foreign Office in London instead filed it as a pending and sent to Foreign Office of India because Abyssinia came under the Raji's remit.[3]

The British had several reasons in stoppage of the letter in relations with its policy of Northeast Africa and cooperation with Ottoman Empire Egypt and Sudan solely dependent on Egypt–Sudanese cotton industry. After two years Tewodros imprisoned Cameron, along many British missionaries (mostly Anglican) and various Europeans to divert the Queen attention. Among the imprisoned people, Henry A. Stern, who previously wrote a book in Europe ascribing Tewodros as "barbaric, cruel unstable usurper".[4]

The British sent a mission under Assyrian-born British subject Hormuzd Rassam, who bore a letter from the Queen in response to Tewodros now three years old letter requesting aid. In response insult resulting from British failure to do exactly what they told, Tewodros added Rassam mission into other European prisoners, breaching diplomatic immunity that led the British launched 1868 Expedition to Abyssinia under Robert Napier.[citation needed] He travelled from India with 13,000 troops and 26,000 camp followers, involving specialist and engineers. When Tewodros reputation immediately degraded by internal rebellion and his harsh methods, the British troop reached Magdala on 10 April and Emperor Tewodros's army decisively defeated. Awaring this, Tewodros released all Europeans and ordered 300 Ethiopians to flung over the cliff. The emperor committed suicide in Easter Monday, 13 April as the British troops stormed citadel of Magdala.[citation needed]

He was buried by British troops at Magdala Medhane Alem (Savior of the World) Orthodox Church under the name of Theodore II.[citation needed]

Post-Zemene Mesafint

Since Emperor Yohannes IV assumption and took control of Tigray Province as well as Christian highlands of Eritrea, the British Napier were there. As he conquered most place the Tekeze including Tselemt, Wolqayt and Tsegede and parts of Semien, Yohannes permitted the British to cross his realm and privilege of local market on the condition that they left the country immediately after the mission. Shortly after returning from Magdala, the British expressed gratitude toward the emperor by giving weapons.

Menelik II

Menelik allowed his rival Kassai to benefit with gifts of modern weapons and supplies from the British. When Tewodros II committed suicide, Menelik arranged his official funeral though he was lamented by his death. When the British diplomat asked why he did this, Menelik replied "to satisfy the passions of the people ... as for me, I should have gone into a forest to weep over ... [his] untimely death ... I have now lost the one who educated me, and toward whom I had always cherished filial and sincere affection."[5]

British journalists such as Augustus B. Wylde and Lord Edward Gleichen wrote about the behavior of Menelik. Wylde wrote:

I had found him a man of great kindness, a remarkably shrewd and clever man and very well informed on most things except on England and her resources; his information on our country evidently having been obtained from persons entirely unfriendly to us; and who did not want Englishmen to have any diplomatic or commercial transactions whatever with Abyssinia [Ethiopia].[6]

After him, Lord Edward Gleichen wrote:

Menelik's manners are pleasant and dignified; he is courteous and kindly, and at the same time simple in manner, giving one the impression of a man who wishes to get at the root of a matter at once, without wasting time in compliments and beating about the bush, so often the characteristics of Oriental potentates...He also aims at being a popular sovereign, accessible to his people at all hours, and ready to listen to their complaints. In this, he appears to be quite successful, for one and all of his subjects seem to bear for him a real affection.[7]

Permanent representation was established soon after founding of Addis Ababa in 1896. During this period, Emperor Menelik II allotted 100 acre of land to British agency at the foot of Entoto Hills. The boundary of the areas defined by natural objects, a spring at the north corner, a prominent rock at the east corner, a stone wall along the south-east side down to the road at the south corner, along the road to west corner and up the creek to the spring. The flattened lower of the site usually had no grass and treeless. By 1908, European-styled British legation was designed by architect Thrift Reavell in the Office of Works, hillside area was selected for residential building. The first building was completed under supervision of WC D'Harty in 1911.[2]

As a Negus, Menelik II enthroned as Emperor in 1889, the British policy makers feared his large-scale expansion. In 1891, they sent a circular note to the other world powers concerning the large portion of Nile Valley belonged to Ethiopia, "the activities and the pretension of the Negus were practically enough in themselves to bring the British to he support of Italian policy in East Africa." To counter the French, who were serious rival in the Nile Valley and the Ethiopian expansion, the British government supported the Italian colonial ambition in Ethiopia. Great British assured Italy's support in Egyptian policy, but would continued if Italy maintain strong dominance in Ethiopia and Menelik support to the French and Russians to undermine Italian hegemony.[8]

On 2 May 1889, Menelik signed Treaty of Wuchale in Italian version. Article 17 of this text contested the use of Italian government in negotiation that allows Ethiopia to enter sovereign great power. On this basis, the Italians believed they entered protectorate over Ethiopia. In later, Menelik became suspicious over the treaty and gathered consultant of chief advisor, Alfred Ilg, and discovered that the Italian misinterpreted the Amharic version of the treaty saying "he might, not that he must, carry on his foreign relations with Italian advice". On this occasion, Menelik was supported by French and Russians allies: the French established in Gulf of Tajurah since 1884 and considered central Ethiopia, including Harar, to be natural hinterland of the Somali Protectorate.[5]

In early 1895, the Italians received report that French agents encouraging protection for Menelik, and the Italian increasingly became involved in Ethiopia and suspected England under which the secret scheme existed between France and Russia, while the French occupies Harar, the British did not express resentment.[8] In 1897, the first Anglo-Ethiopian treaty was signed by British diplomat Rennell Rodd of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Menelik in the issue of border between British Somaliland and lesser the border formed after Battle of Adwa. It was not demarcated until 1932, when Ras Tafari Mekonnen visited Europe in 1924 to demarcate all the Ethiopian borders.[9]

Haile Selassie

On 14 December 1925, Italy signed secret pact with British to grant Italian authority and dominance to the Horn region, in particular to build railway connecting Somalia with Eritrea. The plan was soon leaked and caused provocation of French and Ethiopian government, the latter denounced Britain action as betrayal of a country for intent purpose of League of Nations membership. During Welwel incident onset, the Italian built fort at Welwel oasis in Ogaden region with 21-league limit inside Ethiopian territory. On 23 November 1934, Anglo-Ethiopian boundary commission began studying the definitive boundary in gaze consisted of 600 soldiers and technicians from both Ethiopia and Britain. The Ethiopian government frequently request the Italian authorities in Somaliland to cooperate with the commission. Similarly, the British commissioner Lieutenant-Colonel Esmond Clifford also asked Italians to encamp nearby the region, by which blatantly declined the request. In the event leading to the Abyssinian Crisis, League of Nations exonerated both parties for incident. During the interwar period, Britain and France pledged Italy to ally against Germany, which failed to discourage military buildup on the borders of Italian Eritrea and Somaliland.

Emperor Haile Selassie interaction with Britain broadly began after an Italian invasion of Ethiopia and made an exiled on 3 June 1936 to Britain. During this time, he wrote the first volume of his autobiography and scarcely more than a page to his arrival and residence in England. Three years later when he was considering the second volume, he was joined by British journalist-cum-historian Percy Arnold to assist the draft text. Later, Arnold arrived in Addis Ababa and became member of Menelik Palace in December 1963. There, he began, despite unfamiliar, to inquire background reading in the Ethiopian history.[10]

On 10 June 1940, Mussolini declared war on Britain and France which threatened Egypt from Italian Libya and those around the Italian East Africa. On 20 January 1941, British force along with Ethiopian Gedeon Force, the Arbegnoch and the Emperor arrived Gojjam. From 1940 and early 1941, the British strategy deter Italian force from attacking neighbor British possession. The British accomplished the campaign of northern Ethiopia at the Battle of Keren and the Italian defeat in Eritrea. On 5 May 1941, Haile Selassie entered Addis Ababa to reclaim his throne after 5 years he left, and the Italian totally capitulated at Battle of Gondar in November 1941. The British military officials left responsibility for internal affairs in the emperor's hand, and the interim British administration continued until January 1942 Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement. It stipulated Ethiopia's sovereignty status but only Ogaden and certain areas of French Somaliland, Addis Ababa–Djibouti railroad, Haud became under temporarily British administration. The British Military Mission in Ethiopia successfully suppressed the Woyane Rebellion in 1942, led by Tigray rebel Haile Mariam Redda in favor of Haile Selassie.[11]

In post-occupation, the British played a role of modernizing Ethiopia with infrastructure, social services and healthcare provision as well as monumental and palatial compound was constructed. However, after Ethiopia–US relations strengthen by 1950s, the British influence was waned.[12]

Diaspora

According to 2001 Census, the Ethiopian diaspora community recorded 6,561 which are Ethiopian-born.[13] The 2011 UK Census showed an increase to 15,058 residents in England,[14] 151 in Wales, 258 in Scotland[15] and 27 in Northern Ireland. Of this total of 15,494 Ethiopian-born residents, 10,517 lived in Greater London.[14]

References

- ^ a b "Ethiopia - UK Relations". Embassy of Ethiopia, London. Retrieved 2022-06-11.

- ^ a b "Addis Ababa". Room for Diplomacy. 2015-01-18. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ^ Juterczenka, Sünne (2009). The Fuzzy Logic of Encounter: New Perspectives on Cultural Contact (Cultural Encounters and the Discourses of Scholarship). Waxmann Verlag Gmbh Mrz. ISBN 9783830921240.

- ^ Matthies, Volker (2010). The Siege of Magdala: The British Empire Against the Emperor of Ethiopia. Princeton, New Jersey: Markus Weiner Publishers.

- ^ a b Marcus, Harold (1975). The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia 1844-1913. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 57.

- ^ Hassan, Ahmed "Revisiting Emperor Menelik: A Historical Essay in Reinterpretation, ca.1855-1906" The Journal of Ethiopian Studies, Vol. 49, December, 2016, p.86-87

- ^ Hassan, Ahmed "Revisiting Emperor Menelik: A Historical Essay in Reinterpretation, ca.1855-1906" The Journal of Ethiopian Studies, Vol. 49, December, 2016, p.92-93

- ^ a b MARCUS, HAROLD G. (1963). "A Background to Direct British Diplomatic Involvement in Ethiopia, 1894-1896". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 1 (2): 121–132. ISSN 0304-2243. JSTOR 41965700.

- ^ An overview of these treaties is provided by Harold Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia 1844-1913 (Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press, 1995), pp. 179-190

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (2002). "Emperor Haile Sellassie's Arrival in Britain: An Alternative Autobiographical Draft by Percy Arnold". Northeast African Studies. 9 (2): 1–46. doi:10.1353/nas.2007.0008. ISSN 0740-9133. JSTOR 41931306. S2CID 144707809.

- ^ "3. Ethiopia (1942-present)". uca.edu. Retrieved 2022-06-11.

- ^ Woldesenbet, Wassihun Gebreegizaber (2020-01-01). "The tragedies of a state dominated political economy: shared vices among the imperial, Derg, and EPRDF regimes of Ethiopia". Development Studies Research. 7 (1): 72–82. doi:10.1080/21665095.2020.1785903.

- ^ "Country-of-birth database". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on 11 May 2005. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ a b "2011 Census: Country of birth (expanded), regions in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Country of birth (detailed)" (PDF). National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

External links

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- All articles with vague or ambiguous time

- Vague or ambiguous time from February 2024

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2024

- Ethiopia–United Kingdom relations

- Bilateral relations of Ethiopia

- Bilateral relations of the United Kingdom