Bainbridge–Ropers syndrome

| Bainbridge–Ropers syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

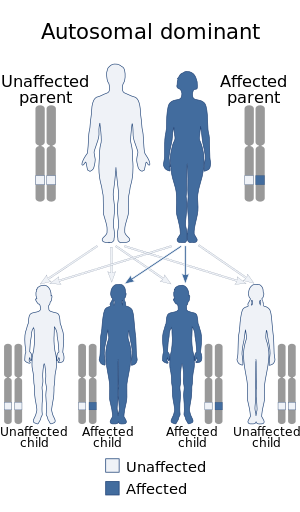

| Bainbridge-Ropers syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Bainbridge–Ropers syndrome is a very rare genetic disorder characterized by abnormalities including severe psychomotor development, feeding problems, severe postnatal growth delays, intellectual disabilities, and skeletal abnormalities.

Signs and symptoms

Morphological features of this syndrome include:[1]

- Arched eyebrows

- Anteverted nares

- Ulnar deviation of the hands

- Microcephaly

- Skeletal abnormalities, such as a "barrel chest", extremely high arched palate

- Crowded teeth

- Hypertelorism (wide-set eyes)

- Scoliosis

Genetics

This condition is caused by a mutation in the ASXL3 gene, which is considered a de novo mutation.[2]

Genetic changes that are described as de novo (new) mutations can be either hereditary or somatic. In some cases, the mutation occurs in a person's egg or sperm cell but is not present in any of the person's other cells. In other cases, the mutation occurs in the fertilized egg shortly after the egg and sperm cells unite. (It is often impossible to tell exactly when a de novo mutation happened.) As the fertilized egg divides, each resulting cell in the growing embryo will have the mutation. De novo mutations may explain genetic disorders in which an affected child has a mutation in every cell in the body but the parents do not, and there is no family history of the disorder.[3]

This condition is inheritable.[4]

Mutations in the Additional Sex Combs Like 3 (ASXL3) gene on the long arm of chromosome 18 (18q12.1) have been associated with this condition.[2]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can only be made by genetic testing.[citation needed]

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

There is no currently known treatment or cure for this condition. However, the symptoms can be treated.[citation needed]

History

This condition was first described by Bainbridge et al in 2013.[2]

References

- ↑ Yu, Kris Pui-Tak; Luk, Ho-Ming; Fung, Jasmine L.F.; Chung, Brian Hon-Yin; Lo, Ivan Fai-Man (January 2021). "Further expanding the clinical phenotype in Bainbridge-Ropers syndrome and dissecting genotype-phenotype correlation in the ASXL3 mutational cluster regions". European Journal of Medical Genetics. 64 (1): 104107. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2020.104107. PMID 33242595. S2CID 227181556.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Bainbridge, Matthew N; Hu, Hao; Muzny, Donna M; Musante, Luciana; Lupski, James R; Graham, Brett H; Chen, Wei; Gripp, Karen W; Jenny, Kim; Wienker, Thomas F; Yang, Yaping; Sutton, V Reid; Gibbs, Richard A; Ropers, H Hilger (2013). "De novo truncating mutations in ASXL3 are associated with a novel clinical phenotype with similarities to Bohring-Opitz syndrome". Genome Medicine. 5 (2): 11. doi:10.1186/gm415. ISSN 1756-994X. PMC 3707024. PMID 23383720.

- ↑ "What is a gene mutation and how do mutations occur?". Genetics Home Reference. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Schirwani, Schaida; Woods, Emily; Koolen, David A.; Ockeloen, Charlotte W.; Lynch, Sally Ann; Kavanagh, Karl; Graham, John M.; Grand, Katheryn; Pierson, Tyler Mark; Chung, Jeffrey M.; Balasubramanian, Meena (January 2023). "Familial Bainbridge‐Ropers syndrome: Report of familial ASXL3 inheritance and a milder phenotype". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 191 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.62981. ISSN 1552-4825. PMC 10087684. PMID 36177608. S2CID 252623193.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmc=value (help)

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Pages with script errors

- Wikipedia articles incorporating the PD-notice template

- CS1 errors: PMC

- Orphaned articles from May 2022

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All orphaned articles

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2021

- Rare genetic syndromes

- Autosomal dominant disorders