Aromanian dialects

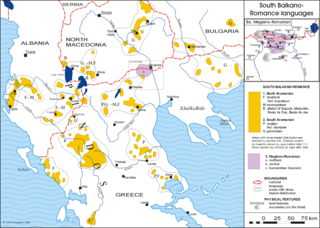

The Aromanian dialects (Aromanian: dialecti or grairi/graire) are the distinct dialects of the Aromanian language. The Aromanians are an ethnic group composed of several subgroups differentiated from each other by, among other things, the dialect they speak. The most important groups are the Pindeans, Gramosteans, Farsherots and Graboveans, each with their respective dialect.[1] The Graboveans and their dialect are referred to by some authors as Moscopoleans[2] and Moscopolean.[3] The Aromanians of the villages of Gopeš (Gopish) and Malovište (Mulovishti) in North Macedonia also have their own distinctive dialect.[4] A few scholars also add the Olympian dialect spoken in Thessaly, Greece,[5] but the majority view is that Olympian is part of Pindean.[6]

The Codex Dimonie, a collection of historical Aromanian-language religious texts translated from Greek, features several characteristics of the Grabovean dialect.[7] In his dictionary of five languages, including Aromanian, the historical Aromanian linguist Nicolae Ianovici made use of the endonym ramanu for "Aromanian". This is typical of the Farsherot dialect, suggesting that Ianovici belonged to the subgroup of Farsherot Aromanians.[8]

Main subdivisions

According to studies done since the start of 20th century two major groups exist generically defined as northern and southern and they often overlap and intermingle in some smaller Aromanian-speaking regions. The main differences between the northern and southern dialects are:[9]

- The spread of syncope. Southern dialects make use of syncope much more frequently. Some forms seen in Southern varieties are exclusive, for example mcari (standard mãcari/mâcari[10]) or altsari (standard anãltsari[11])

- Unstressed /ɛ/ pronounced as /i/. Southern dialects often pronounce unstressed /ɛ/, in particular in final position, as /i/. For example, for the northern carte, feate, seate, the corresponding southern words are carti, feati, seati.

- Voicing of plosive consonants /c/, /p/ and /t/ as /g/, /b/ and /d/ respectively when preceded by nasal consonants. Thus, alantu becomes alandu and mplai becomes mblai in southern dialects.

- Use of va sã vs. va to form future tense. Northern dialects employ constructions of the form: va sã, vu se, va s- (va s-cãntu) while southern dialects use va, vai (vai cãntu).

- Replacement of possessive pronouns with enclitic personal pronouns in the southern dialects, for example hoarã-lã (literally "village-them", meaning "their village")

When historical, demographical, and geographical particularities are taken into account in comparative linguistics the northern or north-western group is further subdivided into grãmostean and fãrsherot while the southern group is mostly represented by pindean.[12]

Grãmostean

The grãmostean dialect was identified in the area nowadays divided between Bulgaria, Greece, and North Macedonia, extending from Vardar to Rila, Pirin, and Rhodopes mountains. The three mountain ranges were important summer pastures for Gramosteans where they had their cãlive - summer settlements for the transhumant shepherds. The largest was Bachița in Rhodopes with over 1000 inhabitants. The grãmostean dialect overlaps with the fãrsherot one in Crushuva (Kruševo).[13] Phonetic particularities of the dialect are the wider use of a-prosthesis (a phenomenon frequent in Romance languages[14]), and depalatalization of t͡ʃ and d͡ʒ for example porțâ - gates, from Latin porta is a homonym of porțâ - pigs, from Latin porcus. In the Bulgarian part ʎ and the consonant groups /kʎ/ and /gʎ/ lenited to /j/, /k/, and /g/ respectively (for example the standard l'epuru becomes iepuru).[15]

Fãrsherot

The fãrsherot dialect is spoken discontinuously over a large area including Albania (mainly the southern half), the western half of North Macedonia, the western part of Epirus, and together with the other two dialects in the Macedonia region of Greece. The dialect is sometimes called moscopolean taking this name from the former city of Moscopole where it was, along with other Aromanian dialects, spoken by the majority of the inhabitants.[16][17] Compared to the grãmostean dialect, the fãrsherot employs less often the a-prothesis. It is also remarkable for the loss of diphthongs for example the breaking of /e/ and /o/ to /e̯a/ and /o̯a/ before /ə/ in the next syllable (Latin feta > Common Romanian *feată) is reverted to fetã in this dialect [18] and the reduction of the /mn/ consonant group to a long /m/. Final /u/ is kept asyllabic as in the other Aromanian dialects but becomes syllabic after a consonant group (ex: cântu), muta cum lingua group (cuscru, aflu), or when preceded by a consonant (capu, patu).[19]

Pindean

The southern dialect of Pindeans is heavily represented in the Pindus mountains area, with other speakers found in Thessaly - including Larissa - and in fewer numbers in Magnesia.[20][21]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Nevaci 2013, p. 103.

- ^ Saramandu & Nevaci 2017, p. 21.

- ^ Saramandu & Nevaci 2017, p. 20.

- ^ Nevaci 2013, p. 115.

- ^ Vrabie, Emil (2000). An English-Aromanian (Macedo-Romanian) Dictionary. Romance Monographs. p. 22. ISBN 1-889441-06-6.

- ^ Saramandu, Nicolae; Nevaci, Manuela (2020). "Atlasul lingvistic al dialectului aromân (ALAR)" (PDF). lingv.ro. p. 31. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ Saramandu & Nevaci 2017, p. 19.

- ^ Lascu 2017, p. 14.

- ^ Capidan, Theodor. "Aromânii. Dialectul aromân (1932)". vdocumente.com (in Romanian). pp. 193–196. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "Dictsiunar". www.dixionline.net. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "Dictsiunar". www.dixionline.net. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin, eds. (30 June 2016). The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages. Oxford University PressOxford. p. 95. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199677108.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967710-8.

- ^ Saramandu, Nicolae (2014). "Atlasul lingvistic al dialectului aromân" [The Linguistic Atlas of the Aromanian Dialect] (PDF). acad.ro. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Sampson, Rodney (29 October 2009). Vowel Prosthesis in Romance: A Diachronic Study. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199541157.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-171609-6.

- ^ Nevaci 2013, p. 119.

- ^ Stavrianos Leften Stavros, Stoianovich Traian. The Balkans since 1453. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000. ISBN 978-1-85065-551-0, p. 278.

- ^ Saramandu, Nicolae (2014). "Atlasul lingvistic al dialectului aromân" [The Linguistic Atlas of the Aromanian Dialect] (PDF). acad.ro. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Markovik, Marjian (2015). "The Aromanian Farsheroti Dialect – Balkan Perspective". ResearchGate.net. pp. 116–117. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Nevaci, Manuela (2021). "Dialectele limbii române - dialecte la distanță" (PDF). lingv.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ Saramandu, Nicolae (2014). "Atlasul lingvistic al dialectului aromân" [The Linguistic Atlas of the Aromanian Dialect] (PDF). acad.ro. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Kahl, Thedle (2011). "Aromanians in Greece: Minority or Vlach-speaking Greeks?". Academia.edu. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

Bibliography

- Lascu, Stoica (2017). "Intelectuali transilvăneni, moldoveni și "aurelieni" despre românii din Balcani (anii '30-'40 ai secolului al XIX-lea" (PDF). Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists: Series on History and Archaeology Sciences (in Romanian). 9 (2): 5–27. ISSN 2067-5682.

- Nevaci, Manuela (2013). "Graiurile aromânești din Peninsula Balcanică. Situația actuală". Fonetică și dialectologie (in Romanian). 32: 103–127.

- Saramandu, Nicolae; Nevaci, Manuela (2017). "The first Aromanian literature: the teaching writings (Theodor Cavallioti, Daniil Moscopolean, Constantin Ucuta)" (PDF). Studia Albanica. 54 (1): 11–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2023.

- CS1 Romanian-language sources (ro)

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Use dmy dates from October 2023

- Articles containing Aromanian-language text

- Pages with plain IPA

- Articles containing Latin-language text

- Aromanian language

- Dialects by language

- All stub articles

- Linguistics stubs