SPAD S.XIII

| S.XIII | |

|---|---|

| |

| SPAD S.XIII in the markings of Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker, U.S. 94th Aero Squadron at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Ohio. | |

| Role | Biplane fighter |

| National origin | France |

| Manufacturer | SPAD |

| Designer | Louis Béchéreau |

| First flight | 4 April 1917[1] |

| Primary users | Aéronautique Militaire Royal Flying Corps (Royal Air Force from April 1918) United States Army Air Service |

| Number built | 8,472[2] |

The SPAD S.XIII is a French biplane fighter aircraft of the First World War, developed by Société Pour L'Aviation et ses Dérivés (SPAD) from the earlier and highly successful SPAD S.VII.

During early 1917, the French designer Louis Béchereau, spurred by the approaching obsolescence of the S.VII, decided to develop two new fighter aircraft, the S.XII and the S.XIII, both using a powerful new geared version of the successful Hispano-Suiza 8A engine. The cannon armament of the S.XII was unpopular, but the S.XIII proved to be one of the most capable fighters of the war, as well as one of the most-produced, with 8,472 built and orders for around 10,000 more cancelled at the Armistice.[2]

By the end of the First World War, the S.XIII had equipped virtually every fighter squadron of the Aéronautique Militaire. In addition, the United States Army Air Service also procured the type in bulk during the conflict, and some replaced or supplemented S.VIIs in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), pending the arrival of Sopwith Dolphins. It proved popular with its pilots and numerous aces from various nations flew the S.XIII. Following the Armistice of 11 November 1918, which marked the end of the First World War, surplus S.XIIIs were sold to both civil and military operators throughout the world.

Development

Background

The origins of the SPAD S.XIII lies in the performance of its predecessor, the SPAD S.VII, a single-seat fighter aircraft powered by a 110 kW (150 hp) direct drive Hispano-Suiza 8A water-cooled V-8 engine and armed with a single synchronised Vickers machine gun. The type had good performance for the time, and entered service with the French Aéronautique Militaire during August 1916.[3] By early 1917, however, the S.VII had been surpassed by the latest German fighters such as the Albatros D.III.[4]

More capable German fighters soon resulted in a shift in aerial supremacy towards the Central Powers, which led to calls for better aircraft.[5] French flying ace Georges Guynemer personally lobbied for an improved S.VII, telling the SPAD's designer Louis Béchereau that "The 150 hp SPAD is not a match for the Halberstadt ... More speed is needed."[6] A quick solution to the problem was to increase the compression ratio of the Hispano-Suiza engine, which increased its power to 130 kW (170 hp) to significantly improve performance, allowing the SPAD S.VII to remain competitive for the time being.[7]

Hispano-Suiza were already in the process of developing a more powerful geared version of the 8A engine,[4] and this engine was chosen by Béchereau to power two developed versions of the S.VII. The British Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a and Sopwith Dolphin fighters would also be powered by the same engine.[5]

Intro flight

The first of Béchereau's designs to fly with the new, reduction gear HS.8B engine design series was the S.XII in its HS.8BeC (or "HS-38") version, which was armed with an unusual 37 mm (1.457 in) cannon that fired through the propeller shaft. However, this aircraft only saw limited use, having been rapidly followed into production by the more conventionally armed S.XIII, which was deemed to be a preferable configuration by several French pilots and officials.[8] Aviation author C.F. Andrews has claimed that a large portion of the credit for the S.XIII lies with Marc Birkigt, the designer of the engine, who had chosen to introduce various innovative features upon it, such as monobloc aluminium cylinders, which were furnished with screwed-in steel liners, which improved its performance.[9]

The SPAD S.XIII flew for the first time on 4 April 1917.[10][11] An early distinguishing feature of the S.XIII – as with the SPAD S.XII – was that its similarly geared HS.8Be V8 engine had a left-handed propeller, which rotating in the opposite rotation to the earlier, direct-drive HS.8A-powered S.VII. Early on, similarly to the British Sopwith Dolphin also powered with HS.8B-series geared V8s, problems were encountered with the gearing, however, Béchereau persisted with the engine, which soon became fairly reliable.[11] Production was ramped up almost immediately after the first flight. Within months of its first flight, the S.XIII had not only entered service with the Aéronautique Militaire but had proven itself to be a successful fighter.[11]

Design

The SPAD S.XIII was a single-engine biplane fighter aircraft. In terms of its construction, it shared a similar configuration and layout to the earlier S.VII,[nb 1] featuring a mainly wooden structure with a fabric covering.[12] It was however generally larger and heavier than its predecessor. Other changes were made to the ailerons, the rounded tips of the tailplanes, the bulkier cowling accommodating the gear-drive Hispano-Suiza 8B engine, and enlarged fin and rudder with a curved trailing edge.[11] The S.XIII was armed with a pair of forward-mounted Vickers machine guns with 400 rounds per gun, which replaced the single gun of the earlier aircraft.[10]

The S.XIII featured relatively conventional construction, that being a wire-braced biplane with a box-shaped fuselage and a nose-mounted engine, except for its interposed wing struts located halfway along the wing span, which gave the fighter the appearance of being a double-bay aircraft instead of a single-bay.[13] This change prevented the landing brace wires from whipping and chafing during flight. Otherwise, it had an orthodox structure, comprising wooden members attached to metal joint fixtures.[13] The fuselage consisted of four square-section longerons, with wooden struts and cross-members while braced with heavy-gauge piano wire. Wire cable was used for the flying and landing wires.[14]

To enable a two-hour endurance, the S.XIII was fitted with several underbelly fuel tanks held within the forward fuselage area which fed into the main service tank in the upper wing center section with an engine-driven pump.[15] Similar pumps were used for supplying pressurised oil and water circulation between the engine's radiator and a header tank was housed within the upper wing. The circular nose radiator incorporated vertical Venetian-style blinds to regulate engine temperatures.[12]

The upper wing was made in one piece, with hollow box-section short spars which connected with linen-wrapped scarf joints, Andrews claims that long runs of spruce were difficult to obtain.[14] Plywood webs and spruce capping strips, which were internally braced with piano wire formed the airfoil. The upper wing was fitted with ailerons, which were actuated by the pilot via a series of tubular pushrods which ran vertical directly beneath the ailerons, with external, 90° bellcranks mounted on top of the lower wings.[15] The lower wing had spruce leading edges and wire-cable trailing edges, while the surfaces were fabric-covered and treated with aircraft dope to produce a scalloped effect.[14]

While the forward Vickers machine guns were standard, they were not always available. As a result of a shortage during the last months of the war, several American S.XIII squadrons replaced Vickers .303 machine guns with the lighter 11.34 kg (25.0 lb) .30/06-calibre Marlin Rockwell M1917 and M1918 aircraft machine guns,[16][17] saving some 7 kg (15 lb)[18] over the Vickers' 30 kg (66 lb), for the guns alone. By the end of the war, about half of American S.XIIIs had been converted.

The powerplant of the S.XIII was a geared Hispano-Suiza engine, at first a 8Ba providing 150 kW (200 hp),[10] but in later aircraft a high-compression 8Bc or 8Be delivering 160 kW (210 hp) was often used.[19] These improvements produced a notable improvement in flight and combat performance.[11] It was faster than its main contemporaries, the British Sopwith Camel and the German Fokker D.VII, and its higher power-to-weight ratio gave it a good rate of climb. The SPAD was renowned for its speed and strength in a dive, although the maneuverability of the type was relatively poor and the aircraft was difficult to control at low speeds, needing to be landed with power on, unlike contemporary fighters like the Nieuport 27 which could be landed with power off.[11]

The geared engines proved to be unreliable, suffering from vibration and poor lubrication. This severely affected serviceability, with it being claimed in November 1917 that the Spad S.XIII was "incapable of giving dependable service". Even in April 1918, an official report stated that two-thirds of the 150 kW (200 hp) SPADs were out of use at any one time due to engine problems.[20] At least one American observer believed at the time that the French were giving the US SPAD XIII squadrons lower-quality engines from their least favored manufacturers while keeping the best for themselves.[citation needed] The reliability issues were an acceptable price to pay for improved performance, however,[21] improved build quality and changes to the engine improved serviceability.[22]

At the beginning of 1918 the Aviation Militaire issued a requirement for a more powerful fighter, in a C1 (Chasseur single-seat) specification. SPAD responded by fitting the 220 kW (300 hp) Hispano-Suiza 8Fb in the SPAD XIII airframe. The structure was strengthened and improved aero-dynamically, retaining the dimensions of the SPAD XIII. Twenty SPAD XVII fighters were built and issued to units with GC 12 (Les Cigones).

Operational history

Deliveries to the Armée de l'Air commenced During May 1917, only one month following the type's first flight.[23] The new aircraft quickly became an important element in the French plans for its fighter force, being expected to replace the SPAD S.VII as well as remaining Nieuport fighters in front line service.

However the slow rate of deliveries disrupted these forecasts and by the end of March 1918, only 764 of the planned 2,230 had been delivered.[24]

Eventually, the S.XIII equipped nearly every French fighter squadron, 74 escadrilles, during the First World War.[25] At the end of the war, plans were underway to replace the S.XIII with several fighter types powered by the 220 kW (300 hp) Hispano-Suiza 8F, such as the Nieuport-Delage NiD 29, the SPAD S.XX and the Sopwith Dolphin II.[26] These plans lapsed following the signing of the Armistice of 11 November 1918, which ended the First World War and the SPAD S.XIII remained in French service as a fighter aircraft until 1923,[16] with Nieuport-Delage NiD 29 deliveries being delayed until 1920.

The S.XIII was flown by numerous famous French fighter pilots such as Rene Fonck (the highest scoring Allied ace, with 75 victories), Georges Guynemer (54 victories), and Charles Nungesser (45 victories), and also by the leading Italian ace Francesco Baracca (34 victories).[27] Aces of the United States Army Air Service who flew the S.XIII include Eddie Rickenbacker (The United State's leading First World War ace with 26 victories) and Frank Luke (18 victories). Andrews attributes the S.XIII's natural stability, which made it a steady gun platform, as the key for its success.[28]

USAAS

Other Allied forces were quick to adopt the new fighter as well and the SPAD XIII equipped 15 of the 16 operational USAAS pursuit squadrons by the Armistice. Prior to the United States entry into the was, American volunteers flying with the Allies had been flying the type.[29] Nearly half of the 893 purchased by the United States were still in service by 1920. In the United States, some S.XIIIs were re-engined with 130 kW (170 hp) Wright-Hispano engines and used to prepare pilots for the new Thomas-Morse MB-3 fighter (which used SPAD-type wings) in 1922. The Wright-Hispano engines were unable to matching the performance of the original powerplant.[29]

RFC

During December 1917, No.23 Squadron Royal Flying Corps (RFC) equipped with the SPAD S.XIII and retaining them until April 1918 when it re-equipped with the Dolphin, while No. 19 Squadron (equipped with the earlier S.VII) also operated at least one S.XIII for a time.[30] The type was used as an interim fighter while awaiting delivery of British-built aircraft.[29]

In his memoir Sagittarius Rising, Cecil Lewis described an aerial competition between himself and a SPAD flown by Guynemer, and Lewis in an SE5, "Their speeds were almost identical, but the high-compression Spad climbed quicker. After the race was over, Guynemeyer and I held a demonstration combat over the aerodrome. Again I was badly worsted. Guynemeyer was all over me. In his hands the Spad was a marvel of flexibility. In the first minute I should have been shot down a dozen times".[31]

Corpo Aeronautico Militare

The S.XIII was also acquired by Italy for the Corpo Aeronautico Militare.[29] Italian pilots expressed a preference for another French-built fighter, the Hanriot HD.1, which was more maneuverable but less powerful. Belgium also operated the S.XIII and one Belgian ace, Edmond Thieffry, came to prominence while piloting the type.[29] After the end of the war, the S.XIII was also exported, including to Japan, Poland and Czechoslovakia.[citation needed]

Gallery

-

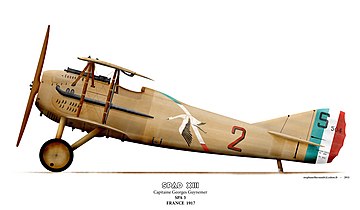

SPAD XIII Georges Guynemer

-

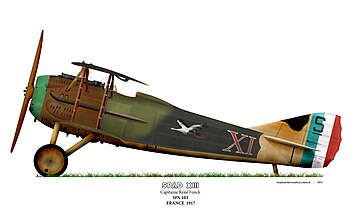

SPAD XIII René Fonck

-

SPAD XIII Edward Rickenbacker

-

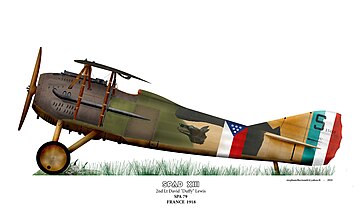

SPAD XIII David "Duffy" Lewis

Operators

- Aviação Militar do Exército Brasileiro (Brazilian Army Aviation) - 1920 to 1930

- Czech Air Force – Postwar.

- Escadrille 3

- Escadrille 12

- Escadrille 15

- Escadrille 16

- Escadrille 23

- Escadrille 26

- Escadrille 31

- Escadrille 37

- Escadrille 38

- Escadrille 48

- Escadrille 49

- Escadrille 57

- Escadrille 62

- Escadrille 65

- Escadrille 67

- Escadrille 68

- Escadrille 69

- Escadrille 73

- Escadrille 75

- Escadrille 76

- Escadrille 77

- Escadrille 78

- Escadrille 79

- Escadrille 80

- Escadrille 81

- Escadrille 82

- Escadrille 83

- Escadrille 84

- Escadrille 85

- Escadrille 86

- Escadrille 87

- Escadrille 88

- Escadrille 89

- Escadrille 90

- Escadrille 91

- Escadrille 92

- Escadrille 93

- Escadrille 94

- Escadrille 95

- Escadrille 96

- Escadrille 97

- Escadrille 98

- Escadrille 99

- Escadrille 100

- Escadrille 102

- Escadrille 103

- Escadrille 112

- Escadrille 124 better known as the Lafayette Escadrille

- Escadrille SPA.124 (Jeanne d'Arc)

- Escadrille 150

- Escadrille 151

- Escadrille 152

- Escadrille 153

- Escadrille 154

- Escadrille 155

- Escadrille 156

- Escadrille 157

- Escadrille 158

- Escadrille 159

- Escadrille 160

- Escadrille 161

- Escadrille 162

- Escadrille 163

- Escadrille 164

- Escadrille 165

- Escadrille 166

- Escadrille 167

- Escadrille 168

- Escadrille 169

- Escadrille 170

- Escadrille 171

- Escadrille 173

- Escadrille 175

- Escadrille 313

- Escadrille 314

- Escadrille 315

- Escadrille 412

- Escadrille 442

- Escadrille 461

- Escadrille 462

- Escadrille 463

- Escadrille 464

- Escadrille 466

- Escadrille 467

- Escadrille 469

- Escadrille 470

- Escadrille 471

- Escadrille 472

- Escadrille 506

- Escadrille 507

- Escadrille 523

- Escadrille 531

- Escadrille 561

- Escadrille Lafayette

- Aéronautique Navale

- Polish Air Force (Postwar)

- Romanian Air Corps (Postwar)[32]

- Soviet Air Force – Taken over from the Imperial Russian Air Force.

- Royal Flying Corps[33]

- No. 19 Squadron RFC – One aircraft

- No. 23 Squadron RFC – December 1917 – May 1918.

Surviving aircraft

Belgium

- SP49 – on static display at the Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History in Brussels.[34]

France

- S4377 – airworthy with the Memorial Flight Association in La Ferté-Alais, Île-de-France.[35][36]

- S5295/S15295 – on static display at the Musée de la Grande Guerre du pays de Meaux, on loan from the Musée de l’air et de l’espace in Paris, Île-de-France.[37] [38]

United States

- S7689 Smith IV – on static display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.[39][40]

- S16594 – on static display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. It is painted to represent Eddie Rickenbacker's aircraft.[41]

- S15155 – on static display at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport 44th Street Sky Train Station in Phoenix, Arizona. Includes parts from three different aircraft[42] and is painted to represent a SPAD XIII flown by Frank Luke.[citation needed]

Specifications (SPAD S.XIII)

Data from French Aircraft of the First World War[43]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 6.25 m (20 ft 6 in)

- Wingspan: 8.25 m (27 ft 1 in) late examples had a span of 8.08 m (26.5 ft)

- Height: 2.60 m (8 ft 6 in)

- Wing area: 21.11 m2 (227.2 sq ft) late examples had a wing area of 20.2 m2 (217 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 601.5 kg (1,326 lb)

- Gross weight: 856.5 kg (1,888 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Hispano-Suiza 8Ba, Bb or Bd Water cooled 8-cylinder vee-type, 150 kW (200 hp)

- Propellers: 2-bladed

Performance

- Maximum speed: 211 km/h (131 mph, 114 kn) at 1,000 m (3,300 ft)

- 208.5 km/h (129.6 mph; 112.6 kn) at 2,000 m (6,600 ft)

- 205.5 km/h (127.7 mph; 111.0 kn) at 3,000 m (9,800 ft)

- 201 km/h (125 mph; 109 kn) at 4,000 m (13,000 ft)

- 190 km/h (120 mph; 100 kn) at 5,000 m (16,000 ft)

- Endurance: 2 hours

- Service ceiling: 6,800 m (22,300 ft)

- Time to altitude:

- 2 minutes 20 seconds to 1,000 m (3,300 ft)

- 5 minutes 17 seconds to 2,000 m (6,600 ft)

- 8 minutes 45 seconds to 3,000 m (9,800 ft)

- 13 minutes 5 seconds to 4,000 m (13,000 ft)

- 20 minutes 10 seconds to 5,000 m (16,000 ft)

- Wing loading: 40 kg/m2 (8.2 lb/sq ft)

Armament

- Guns: 2 × .303 in (7.70 mm) Vickers machine guns or on USAS Examples, 2 × Marlin M1917 or M1918 machine guns

- Bombs: 4 × 25 lb (11 kg) Cooper bombs

See also

- Early Bird Spad 13, a homebuilt replica of the SPAD S.XIII

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Ansaldo Balilla

- Fokker D.VII

- Morane-Saulnier AF

- Morane-Saulnier AI

- Nieuport 28

- Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a

- Salmson 3 C.1

- Sopwith Camel

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ Winchester 2006, p. 23.

- ^ a b Sharpe 2000, p. 272.

- ^ Bruce Air Enthusiast Fifteen, pp. 58–60.

- ^ a b Andrews 1965, p. 4.

- ^ a b Andrews 1965, pp. 4-5.

- ^ Bruce Air International May 1976, p. 240.

- ^ Bruce Air Enthusiast Fifteen, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Bruce Air International May 1976, pp. 240–242.

- ^ Andrews 1965, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Bruce Air International June 1976, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d e f g Andrews 1965, p. 6.

- ^ a b Andrews 1965, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Andrews 1965, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c Andrews 1965, p. 7.

- ^ a b Andrews 1965, p. 8.

- ^ a b Bruce Air International June 1976, p. 312.

- ^ Maurer 1978, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Archived Marlin M1917/18 machine gun specification page

- ^ Bruce Air International June 1976, p. 292.

- ^ Bruce Air International June 1976, p. 291.

- ^ Bruce Air International June 1976, p. 293.

- ^ Bruce et al. 1969, p. 9.

- ^ Bruce Air International June 1976, p. 280.

- ^ Bruce Air International June 1976, pp. 290–291.

- ^ Bruce Air International June 1976, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Bruce Air International June 1976, p. 310.

- ^ Andrews 1965, pp. 8-10.

- ^ Andrews 1965, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Andrews 1965, p. 10.

- ^ Bruce 1982, pp. 561–563.

- ^ Sagittarius Rising, Cecil Lewis

- ^ "Modelism International - Spad Vii-Xiii en Romania PDF" (in Romanian).

- ^ Bruce 1982, pp. 561–564.

- ^ "Airframe Dossier – Societe Pour lAviation et ses Derives (SPAD)XIII, c/n SP-49". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Spad XIII C1". Memorial Flight. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Immatriculation des aéronefs [F-AZFP]" (in French). Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- ^ "Airframe Dossier – Societe Pour lAviation et ses Derives (SPAD)XIII, s/n S5295 RAF, c/n S5295". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "SPAD XIII C1 n° 15295 Code S-5295 - Museum of the Great War - Meaux (77) -" (in French). Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ "Spad XIII "Smith IV"". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Airframe Dossier – Societe Pour lAviation et ses Derives (SPAD)XIII, s/n 7689". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- ^ "SPAD XIII C.1". National Museum of the US Air Force. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "SPAD XIII at Sky Harbor International". Skytamer. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ Davilla, 1997, p.509

Bibliography

- Andrews, C.F. Profile No 17: The SPAD XIII C.1. Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications, 1965.

- Bruce, J.M. The Aeroplanes of the Royal Flying Corps (Military Wing). London: Putnam, 1982. ISBN 0-370-30084-X.

- Bruce, J.M. "The First Fighting SPADs". Air Enthusiast, Issue 15, April–July 1981, pp. 58–77. Bromley, Kent: Pilot Press. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Bruce, J.M. "Spad Story: Part One". Air International, Vol. 10, No. 5, May 1976, pp. 237–242. Bromley, UK: Fine Scroll.

- Bruce, J.M. "Spad Story: Part Two". Air International, Vol. 10, No. 6, June 1976, pp. 289–296, 310–312. Bromley, UK: Fine Scroll.

- Bruce, J.M., Michael P. Rolfe and Richard Ward. AircamAviation Series No 9: Spad Scouts SVII–SXIII. Canterbury, UK: Osprey, 1968. ISBN 0-85045-009-8.

- Bruner, Georges (1977). "Fighters a la Francaise, Part One". Air Enthusiast (3): 85–95. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Davilla, Dr. James J.; Soltan, Arthur (1997). French Aircraft of the First World War. Mountain View, CA: Flying Machines Press. ISBN 978-1891268090.

- Kudlicka, Bohumir (September 2001). "Des avions français en Tchécoslovaquie: les unités de chasse sur Spad" [French Aircraft in Czechoslovakia: Everyone Goes Down!]. Avions: Toute l'Aéronautique et son histoire: Tout le monde descende! (in French) (102): 54–58. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Maurer, Maurer, ed. The U.S. Air Service in World War I: Volume I: The Final Report and a Tactical History. Washington, D.C.: The Office of Air Force History, USAF, 1978.

- Sharpe, Michael. Biplanes, Triplanes, and Seaplanes. London: Friedman/Fairfax Books, 2000. ISBN 1-58663-300-7.

- Winchester, Jim. Fighter: The World's Finest Combat Aircraft – 1913 to the Present Day. New York: Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc. and Parragon Publishing, 2006. ISBN 0-7607-7957-0.

External links

- CS1 Romanian-language sources (ro)

- CS1 French-language sources (fr)

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2012

- Articles containing French-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2018

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2019

- Commons category link is on Wikidata

- Articles with J9U identifiers

- Articles with LCCN identifiers

- 1910s French fighter aircraft

- Military aircraft of World War I

- SPAD aircraft

- Aircraft first flown in 1917

- Biplanes

- Single-engined tractor aircraft