Feedback

| Complex systems |

|---|

| Topics |

Feedback occurs when outputs of a system are routed back as inputs as part of a chain of cause-and-effect that forms a circuit or loop.[1] The system can then be said to feed back into itself. The notion of cause-and-effect has to be handled carefully when applied to feedback systems:

Simple causal reasoning about a feedback system is difficult because the first system influences the second and second system influences the first, leading to a circular argument. This makes reasoning based upon cause and effect tricky, and it is necessary to analyze the system as a whole. As provided by Webster, feedback in business is the transmission of evaluative or corrective information about an action, event, or process to the original or controlling source.[2]

— Karl Johan Åström and Richard M.Murray, Feedback Systems: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers[3]

History

Self-regulating mechanisms have existed since antiquity, and the idea of feedback had started to enter economic theory in Britain by the 18th century, but it was not at that time recognized as a universal abstraction and so did not have a name.[4]

The first ever known artificial feedback device was a float valve, for maintaining water at a constant level, invented in 270 BC in Alexandria, Egypt.[5] This device illustrated the principle of feedback: a low water level opens the valve, the rising water then provides feedback into the system, closing the valve when the required level is reached. This then reoccurs in a circular fashion as the water level fluctuates.[5]

Centrifugal governors were used to regulate the distance and pressure between millstones in windmills since the 17th century. In 1788, James Watt designed his first centrifugal governor following a suggestion from his business partner Matthew Boulton, for use in the steam engines of their production. Early steam engines employed a purely reciprocating motion, and were used for pumping water – an application that could tolerate variations in the working speed, but the use of steam engines for other applications called for more precise control of the speed.

In 1868, James Clerk Maxwell wrote a famous paper, "On governors", that is widely considered a classic in feedback control theory.[6] This was a landmark paper on control theory and the mathematics of feedback.

The verb phrase to feed back, in the sense of returning to an earlier position in a mechanical process, was in use in the US by the 1860s,[7][8] and in 1909, Nobel laureate Karl Ferdinand Braun used the term "feed-back" as a noun to refer to (undesired) coupling between components of an electronic circuit.[9]

By the end of 1912, researchers using early electronic amplifiers (audions) had discovered that deliberately coupling part of the output signal back to the input circuit would boost the amplification (through regeneration), but would also cause the audion to howl or sing.[10] This action of feeding back of the signal from output to input gave rise to the use of the term "feedback" as a distinct word by 1920.[10]

The development of cybernetics from the 1940s onwards was centred around the study of circular causal feedback mechanisms.

Over the years there has been some dispute as to the best definition of feedback. According to cybernetician Ashby (1956), mathematicians and theorists interested in the principles of feedback mechanisms prefer the definition of "circularity of action", which keeps the theory simple and consistent. For those with more practical aims, feedback should be a deliberate effect via some more tangible connection.

[Practical experimenters] object to the mathematician's definition, pointing out that this would force them to say that feedback was present in the ordinary pendulum ... between its position and its momentum—a "feedback" that, from the practical point of view, is somewhat mystical. To this the mathematician retorts that if feedback is to be considered present only when there is an actual wire or nerve to represent it, then the theory becomes chaotic and riddled with irrelevancies.[11]: 54

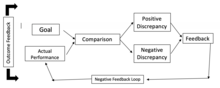

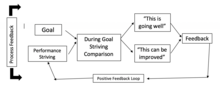

Focusing on uses in management theory, Ramaprasad (1983) defines feedback generally as "...information about the gap between the actual level and the reference level of a system parameter" that is used to "alter the gap in some way". He emphasizes that the information by itself is not feedback unless translated into action.[12]

Types

Positive and negative feedback

Positive feedback: If the signal feedback from output is in phase with the input signal, the feedback is called positive feedback.

Negative feedback: If the signal feedback is out of phase by 180° with respect to the input signal, the feedback is called negative feedback.

As an example of negative feedback, the diagram might represent a cruise control system in a car that matches a target speed such as the speed limit. The controlled system is the car; its input includes the combined torque from the engine and from the changing slope of the road (the disturbance). The car's speed (status) is measured by a speedometer. The error signal is the difference of the speed as measured by the speedometer from the target speed (set point). The controller interprets the speed to adjust the accelerator, commanding the fuel flow to the engine (the effector). The resulting change in engine torque, the feedback, combines with the torque exerted by the change of road grade to reduce the error in speed, minimising the changing slope.

The terms "positive" and "negative" were first applied to feedback prior to WWII. The idea of positive feedback already existed in the 1920s when the regenerative circuit was made.[13] Friis and Jensen (1924) described this circuit in a set of electronic amplifiers as a case where the "feed-back" action is positive in contrast to negative feed-back action, which they mentioned only in passing.[14] Harold Stephen Black's classic 1934 paper first details the use of negative feedback in electronic amplifiers. According to Black:

Positive feed-back increases the gain of the amplifier, negative feed-back reduces it.[15]

According to Mindell (2002) confusion in the terms arose shortly after this:

... Friis and Jensen had made the same distinction Black used between "positive feed-back" and "negative feed-back", based not on the sign of the feedback itself but rather on its effect on the amplifier's gain. In contrast, Nyquist and Bode, when they built on Black's work, referred to negative feedback as that with the sign reversed. Black had trouble convincing others of the utility of his invention in part because confusion existed over basic matters of definition.[13]: 121

Even before these terms were being used, James Clerk Maxwell had described their concept through several kinds of "component motions" associated with the centrifugal governors used in steam engines. He distinguished those that lead to a continued increase in a disturbance or the amplitude of a wave or oscillation, from those that lead to a decrease of the same quality.[16]

Terminology

The terms positive and negative feedback are defined in different ways within different disciplines.

- the change of the gap between reference and actual values of a parameter or trait, based on whether the gap is widening (positive) or narrowing (negative).[12]

- the valence of the action or effect that alters the gap, based on whether it makes the recipient or observer happy (positive) or unhappy (negative).[17]

The two definitions may be confusing, like when an incentive (reward) is used to boost poor performance (narrow a gap). Referring to definition 1, some authors use alternative terms, replacing positive and negative with self-reinforcing and self-correcting,[18] reinforcing and balancing,[19] discrepancy-enhancing and discrepancy-reducing[20] or regenerative and degenerative[21] respectively. And for definition 2, some authors promote describing the action or effect as positive and negative reinforcement or punishment rather than feedback.[12][22] Yet even within a single discipline an example of feedback can be called either positive or negative, depending on how values are measured or referenced.[23]

This confusion may arise because feedback can be used to provide information or motivate, and often has both a qualitative and a quantitative component. As Connellan and Zemke (1993) put it:

Quantitative feedback tells us how much and how many. Qualitative feedback tells us how good, bad or indifferent.[24]: 102

Limitations of negative and positive feedback

While simple systems can sometimes be described as one or the other type, many systems with feedback loops cannot be shoehorned into either type, and this is especially true when multiple loops are present.

When there are only two parts joined so that each affects the other, the properties of the feedback give important and useful information about the properties of the whole. But when the parts rise to even as few as four, if every one affects the other three, then twenty circuits can be traced through them; and knowing the properties of all the twenty circuits does not give complete information about the system.[11]: 54

Other types of feedback

In general, feedback systems can have many signals fed back and the feedback loop frequently contain mixtures of positive and negative feedback where positive and negative feedback can dominate at different frequencies or different points in the state space of a system.

The term bipolar feedback has been coined to refer to biological systems where positive and negative feedback systems can interact, the output of one affecting the input of another, and vice versa.[25]

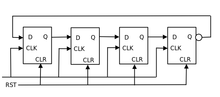

Some systems with feedback can have very complex behaviors such as chaotic behaviors in non-linear systems, while others have much more predictable behaviors, such as those that are used to make and design digital systems.

Feedback is used extensively in digital systems. For example, binary counters and similar devices employ feedback where the current state and inputs are used to calculate a new state which is then fed back and clocked back into the device to update it.

Applications

Mathematics and dynamical systems

By using feedback properties, the behavior of a system can be altered to meet the needs of an application; systems can be made stable, responsive or held constant. It is shown that dynamical systems with a feedback experience an adaptation to the edge of chaos.[26]

Physics

Physical systems present feedback through the mutual interactions of its parts. Feedback is also relevant for the regulation of experimental conditions, noise reduction, and signal control.[27] The thermodynamics of feedback-controlled systems has intrigued physicist since the Maxwell's demon, with recent advances on the consequences for entropy reduction and performance increase.[28][29]

Biology

In biological systems such as organisms, ecosystems, or the biosphere, most parameters must stay under control within a narrow range around a certain optimal level under certain environmental conditions. The deviation of the optimal value of the controlled parameter can result from the changes in internal and external environments. A change of some of the environmental conditions may also require change of that range to change for the system to function. The value of the parameter to maintain is recorded by a reception system and conveyed to a regulation module via an information channel. An example of this is insulin oscillations.

Biological systems contain many types of regulatory circuits, both positive and negative. As in other contexts, positive and negative do not imply that the feedback causes good or bad effects. A negative feedback loop is one that tends to slow down a process, whereas the positive feedback loop tends to accelerate it. The mirror neurons are part of a social feedback system, when an observed action is "mirrored" by the brain—like a self-performed action.

Normal tissue integrity is preserved by feedback interactions between diverse cell types mediated by adhesion molecules and secreted molecules that act as mediators; failure of key feedback mechanisms in cancer disrupts tissue function.[30] In an injured or infected tissue, inflammatory mediators elicit feedback responses in cells, which alter gene expression, and change the groups of molecules expressed and secreted, including molecules that induce diverse cells to cooperate and restore tissue structure and function. This type of feedback is important because it enables coordination of immune responses and recovery from infections and injuries. During cancer, key elements of this feedback fail. This disrupts tissue function and immunity.[31][32]

Mechanisms of feedback were first elucidated in bacteria, where a nutrient elicits changes in some of their metabolic functions.[33] Feedback is also central to the operations of genes and gene regulatory networks. Repressor (see Lac repressor) and activator proteins are used to create genetic operons, which were identified by François Jacob and Jacques Monod in 1961 as feedback loops.[34] These feedback loops may be positive (as in the case of the coupling between a sugar molecule and the proteins that import sugar into a bacterial cell), or negative (as is often the case in metabolic consumption).

On a larger scale, feedback can have a stabilizing effect on animal populations even when profoundly affected by external changes, although time lags in feedback response can give rise to predator-prey cycles.[35]

In zymology, feedback serves as regulation of activity of an enzyme by its direct product(s) or downstream metabolite(s) in the metabolic pathway (see Allosteric regulation).

The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis is largely controlled by positive and negative feedback, much of which is still unknown.

In psychology, the body receives a stimulus from the environment or internally that causes the release of hormones. Release of hormones then may cause more of those hormones to be released, causing a positive feedback loop. This cycle is also found in certain behaviour. For example, "shame loops" occur in people who blush easily. When they realize that they are blushing, they become even more embarrassed, which leads to further blushing, and so on.[36]

Climate science

The climate system is characterized by strong positive and negative feedback loops between processes that affect the state of the atmosphere, ocean, and land. A simple example is the ice–albedo positive feedback loop whereby melting snow exposes more dark ground (of lower albedo), which in turn absorbs heat and causes more snow to melt.

Control theory

Feedback is extensively used in control theory, using a variety of methods including state space (controls), full state feedback, and so forth. In the context of control theory, "feedback" is traditionally assumed to specify "negative feedback".[40]

The most common general-purpose controller using a control-loop feedback mechanism is a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller. Heuristically, the terms of a PID controller can be interpreted as corresponding to time: the proportional term depends on the present error, the integral term on the accumulation of past errors, and the derivative term is a prediction of future error, based on current rate of change.[41]

Education

For feedback in the educational context, see corrective feedback.

Mechanical engineering

In ancient times, the float valve was used to regulate the flow of water in Greek and Roman water clocks; similar float valves are used to regulate fuel in a carburettor and also used to regulate tank water level in the flush toilet.

The Dutch inventor Cornelius Drebbel (1572-1633) built thermostats (c1620) to control the temperature of chicken incubators and chemical furnaces. In 1745, the windmill was improved by blacksmith Edmund Lee, who added a fantail to keep the face of the windmill pointing into the wind. In 1787, Tom Mead regulated the rotation speed of a windmill by using a centrifugal pendulum to adjust the distance between the bedstone and the runner stone (i.e., to adjust the load).

The use of the centrifugal governor by James Watt in 1788 to regulate the speed of his steam engine was one factor leading to the Industrial Revolution. Steam engines also use float valves and pressure release valves as mechanical regulation devices. A mathematical analysis of Watt's governor was done by James Clerk Maxwell in 1868.[16]

The Great Eastern was one of the largest steamships of its time and employed a steam powered rudder with feedback mechanism designed in 1866 by John McFarlane Gray. Joseph Farcot coined the word servo in 1873 to describe steam-powered steering systems. Hydraulic servos were later used to position guns. Elmer Ambrose Sperry of the Sperry Corporation designed the first autopilot in 1912. Nicolas Minorsky published a theoretical analysis of automatic ship steering in 1922 and described the PID controller.[42]

Internal combustion engines of the late 20th century employed mechanical feedback mechanisms such as the vacuum timing advance but mechanical feedback was replaced by electronic engine management systems once small, robust and powerful single-chip microcontrollers became affordable.

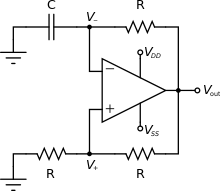

Electronic engineering

The use of feedback is widespread in the design of electronic components such as amplifiers, oscillators, and stateful logic circuit elements such as flip-flops and counters. Electronic feedback systems are also very commonly used to control mechanical, thermal and other physical processes.

If the signal is inverted on its way round the control loop, the system is said to have negative feedback;[44] otherwise, the feedback is said to be positive. Negative feedback is often deliberately introduced to increase the stability and accuracy of a system by correcting or reducing the influence of unwanted changes. This scheme can fail if the input changes faster than the system can respond to it. When this happens, the lag in arrival of the correcting signal can result in over-correction, causing the output to oscillate or "hunt".[45] While often an unwanted consequence of system behaviour, this effect is used deliberately in electronic oscillators.

Harry Nyquist at Bell Labs derived the Nyquist stability criterion for determining the stability of feedback systems. An easier method, but less general, is to use Bode plots developed by Hendrik Bode to determine the gain margin and phase margin. Design to ensure stability often involves frequency compensation to control the location of the poles of the amplifier.

Electronic feedback loops are used to control the output of electronic devices, such as amplifiers. A feedback loop is created when all or some portion of the output is fed back to the input. A device is said to be operating open loop if no output feedback is being employed and closed loop if feedback is being used.[46]

When two or more amplifiers are cross-coupled using positive feedback, complex behaviors can be created. These multivibrators are widely used and include:

- astable circuits, which act as oscillators

- monostable circuits, which can be pushed into a state, and will return to the stable state after some time

- bistable circuits, which have two stable states that the circuit can be switched between

Negative feedback

Negative feedback occurs when the fed-back output signal has a relative phase of 180° with respect to the input signal (upside down). This situation is sometimes referred to as being out of phase, but that term also is used to indicate other phase separations, as in "90° out of phase". Negative feedback can be used to correct output errors or to desensitize a system to unwanted fluctuations.[47] In feedback amplifiers, this correction is generally for waveform distortion reduction[citation needed] or to establish a specified gain level. A general expression for the gain of a negative feedback amplifier is the asymptotic gain model.

Positive feedback

Positive feedback occurs when the fed-back signal is in phase with the input signal. Under certain gain conditions, positive feedback reinforces the input signal to the point where the output of the device oscillates between its maximum and minimum possible states. Positive feedback may also introduce hysteresis into a circuit. This can cause the circuit to ignore small signals and respond only to large ones. It is sometimes used to eliminate noise from a digital signal. Under some circumstances, positive feedback may cause a device to latch, i.e., to reach a condition in which the output is locked to its maximum or minimum state. This fact is very widely used in digital electronics to make bistable circuits for volatile storage of information.

The loud squeals that sometimes occurs in audio systems, PA systems, and rock music are known as audio feedback. If a microphone is in front of a loudspeaker that it is connected to, sound that the microphone picks up comes out of the speaker, and is picked up by the microphone and re-amplified. If the loop gain is sufficient, howling or squealing at the maximum power of the amplifier is possible.

Oscillator

An electronic oscillator is an electronic circuit that produces a periodic, oscillating electronic signal, often a sine wave or a square wave.[48][49] Oscillators convert direct current (DC) from a power supply to an alternating current signal. They are widely used in many electronic devices. Common examples of signals generated by oscillators include signals broadcast by radio and television transmitters, clock signals that regulate computers and quartz clocks, and the sounds produced by electronic beepers and video games.[48]

Oscillators are often characterized by the frequency of their output signal:

- A low-frequency oscillator (LFO) is an electronic oscillator that generates a frequency below ≈20 Hz. This term is typically used in the field of audio synthesizers, to distinguish it from an audio frequency oscillator.

- An audio oscillator produces frequencies in the audio range, about 16 Hz to 20 kHz.[49]

- An RF oscillator produces signals in the radio frequency (RF) range of about 100 kHz to 100 GHz.[49]

Oscillators designed to produce a high-power AC output from a DC supply are usually called inverters.

There are two main types of electronic oscillator: the linear or harmonic oscillator and the nonlinear or relaxation oscillator.[49][50]

Latches and flip-flops

A latch or a flip-flop is a circuit that has two stable states and can be used to store state information. They typically constructed using feedback that crosses over between two arms of the circuit, to provide the circuit with a state. The circuit can be made to change state by signals applied to one or more control inputs and will have one or two outputs. It is the basic storage element in sequential logic. Latches and flip-flops are fundamental building blocks of digital electronics systems used in computers, communications, and many other types of systems.

Latches and flip-flops are used as data storage elements. Such data storage can be used for storage of state, and such a circuit is described as sequential logic. When used in a finite-state machine, the output and next state depend not only on its current input, but also on its current state (and hence, previous inputs). It can also be used for counting of pulses, and for synchronizing variably-timed input signals to some reference timing signal.

Flip-flops can be either simple (transparent or opaque) or clocked (synchronous or edge-triggered). Although the term flip-flop has historically referred generically to both simple and clocked circuits, in modern usage it is common to reserve the term flip-flop exclusively for discussing clocked circuits; the simple ones are commonly called latches.[51][52]

Using this terminology, a latch is level-sensitive, whereas a flip-flop is edge-sensitive. That is, when a latch is enabled it becomes transparent, while a flip flop's output only changes on a single type (positive going or negative going) of clock edge.

Software

Feedback loops provide generic mechanisms for controlling the running, maintenance, and evolution of software and computing systems.[53] Feedback-loops are important models in the engineering of adaptive software, as they define the behaviour of the interactions among the control elements over the adaptation process, to guarantee system properties at run-time. Feedback loops and foundations of control theory have been successfully applied to computing systems.[54] In particular, they have been applied to the development of products such as IBM Db2 and IBM Tivoli. From a software perspective, the autonomic (MAPE, monitor analyze plan execute) loop proposed by researchers of IBM is another valuable contribution to the application of feedback loops to the control of dynamic properties and the design and evolution of autonomic software systems.[55][56]

Software Development

User interface design

Feedback is also a useful design principle for designing user interfaces.

Video feedback

Video feedback is the video equivalent of acoustic feedback. It involves a loop between a video camera input and a video output, e.g., a television screen or monitor. Aiming the camera at the display produces a complex video image based on the feedback.[57]

Human resource management

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (September 2020) |

See also

- Corrective feedback – Practice in the field of learning and achievement

- Audio feedback – Howling caused by a circular path in an audio system

- Black box – System where only the inputs and outputs can be viewed, and not its implementation (see "experiment model")

- Cybernetics – Transdisciplinary field concerned with regulatory and purposive systems

- Feed forward – Control paradigm in which errors are measured before they can affect a system

- Fundamental interaction – Most basic type of physical force

- Human–computer interaction – Academic discipline studying the relationship between computer systems and their users, which also includes:

- Low-key feedback – In human-computer interaction, low-key feedback is output that takes a background role

- Optical feedback – Loop delay that occurs when a video camera is pointed at its own playback video monitor

- Perverse incentive – Incentive that has a contrary result

- Recursion – Process of repeating items in a self-similar way

- Resonance – Tendency to oscillate at certain frequencies

- Stability criterion

- Strange loop – Cyclic structure that goes through several levels in a hierarchical system

- Unintended consequences – Unforeseen outcomes of an action

References

- ^ Andrew Ford (2010). "Chapter 9: Information feedback and causal loop diagrams". Modeling the Environment. Island Press. pp. 99 ff. ISBN 9781610914253.

This chapter describes causal loop diagrams to portray the information feedback at work in a system. The word causal refers to cause-and-effect relationships. The wordloop refers to a closed chain of cause and effect that creates the feedback.

- ^ "feedback". MerriamWebster. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Karl Johan Åström; Richard M. Murray (2008). "§1.1: What is feedback?". Feedback Systems: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers. Princeton University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9781400828739. Online version found here.

- ^ Otto Mayr (1989). Authority, liberty, & automatic machinery in early modern Europe. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-3939-9.

- ^ a b Moloney, Jules (2011). Designing Kinetics for Architectural Facades. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415610346.

- ^ Maxwell, James Clerk (1868). "On Governors". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 16: 270–283. doi:10.1098/rspl.1867.0055. JSTOR 112510.

- ^ "Heretofore ... it has been necessary to reverse the motion of the rollers, thus causing the material to travel or feed back, ..." HH Cole, "Improvement in Fluting-Machines", US Patent 55,469 (1866) accessed 23 March 2012.

- ^ "When the journal or spindle is cut ... and the carriage is about to feed back by a change of the sectional nut or burr upon the screw-shafts, the operator seizes the handle..." JM Jay, "Improvement in Machines for Making the Spindles of Wagon-Axles", US Patent 47,769 (1865) accessed 23 March 2012.

- ^ "...as far as possible the circuit has no feed-back into the system being investigated." [1] Karl Ferdinand Braun, "Electrical oscillations and wireless telegraphy", Nobel Lecture, 11 December 1909. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ a b Stuart Bennett (1979). A history of control engineering, 1800–1930. Stevenage; New York: Peregrinus for the Institution of Electrical Engineers. ISBN 978-0-906048-07-8. [2]

- ^ a b W. Ross Ashby (1957). An introduction to cybernetics (PDF). Chapman & Hall. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 August 2000.

- ^ a b c Ramaprasad, Arkalgud (1983). "On the definition of feedback". Behavioral Science. 28: 4–13. doi:10.1002/bs.3830280103.

- ^ a b David A. Mindell (2002). Between Human and Machine : Feedback, Control, and Computing before Cybernetics. Baltimore, MD, US: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801868955.

- ^ Friis, H.T., and A.G.Jensen. "High Frequency Amplifiers" Bell System Technical Journal 3 (April 1924):181–205.

- ^ H.S. Black, "Stabilized feed-back amplifiers", Electrical Engineering, vol. 53, pp. 114–120, January 1934.

- ^ a b Maxwell, James Clerk (1868). "On Governors" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 16: 270–283. doi:10.1098/rspl.1867.0055. S2CID 51751195. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 December 2010.

- ^ Herold, David M., and Martin M. Greller. "Research Notes. FEEDBACK THE DEFINITION OF A CONSTRUCT." Academy of management Journal 20.1 (1977): 142-147.

- ^ Peter M. Senge (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-385-26094-7.

- ^ John D. Sterman, Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World, McGraw Hill/Irwin, 2000. ISBN 978-0-07-238915-9

- ^ Charles S. Carver, Michael F. Scheier: On the Self-Regulation of Behavior Cambridge University Press, 2001

- ^ Hermann A Haus and Richard B. Adler, Circuit Theory of Linear Noisy Networks, MIT Press, 1959

- ^ BF Skinner, The Experimental Analysis of Behavior, American Scientist, Vol. 45, No. 4 (SEPTEMBER 1957), pp. 343-371

- ^ "However, after scrutinizing the statistical properties of the structural equations, the members of the committee assured themselves that it is possible to have a significant positive feedback loop when using standardized scores, and a negative loop when using real scores." Ralph L. Levine, Hiram E. Fitzgerald. Analysis of the dynamic psychological systems: methods and applications, ISBN 978-0306437465 (1992) page 123

- ^ Thomas K. Connellan and Ron Zemke, "Sustaining Knock Your Socks Off Service" AMACOM, 1 July 1993. ISBN 0-8144-7824-7

- ^ Alta Smit; Arturo O'Byrne (2011). "Bipolar feedback". Introduction to Bioregulatory Medicine. Thieme. p. 6. ISBN 9783131469717.

- ^ Wotherspoon, T.; Hubler, A. (2009). "Adaptation to the edge of chaos with random-wavelet feedback". J. Phys. Chem. A. 113 (1): 19–22. Bibcode:2009JPCA..113...19W. doi:10.1021/jp804420g. PMID 19072712.

- ^ Bechhoefer, John (31 August 2005). "Feedback for physicists: A tutorial essay on control". Reviews of Modern Physics. 77 (3): 783–836. Bibcode:2005RvMP...77..783B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.77.783.

- ^ Sagawa, Takahiro; Ueda, Masahito (26 February 2008). "Second Law of Thermodynamics with Discrete Quantum Feedback Control". Physical Review Letters. 100 (8): 080403. arXiv:0710.0956. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100h0403S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.080403. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 18352605.

- ^ Cao, F. J.; Feito, M. (10 April 2009). "Thermodynamics of feedback controlled systems". Physical Review E. 79 (4): 041118. arXiv:0805.4824. Bibcode:2009PhRvE..79d1118C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.79.041118. ISSN 1539-3755. PMID 19518184.

- ^ Vlahopoulos, SA; Cen, O; Hengen, N; Agan, J; Moschovi, M; Critselis, E; Adamaki, M; Bacopoulou, F; Copland, JA; Boldogh, I; Karin, M; Chrousos, GP (20 June 2015). "Dynamic aberrant NF-κB spurs tumorigenesis: A new model encompassing the microenvironment". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 26 (4): 389–403. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.06.001. PMC 4526340. PMID 26119834.

- ^ Vlahopoulos, SA (August 2017). "Aberrant control of NF-κB in cancer permits transcriptional and phenotypic plasticity, to curtail dependence on host tissue: molecular mode". Cancer Biology & Medicine. 14 (3): 254–270. doi:10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2017.0029. PMC 5570602. PMID 28884042.

- ^ Korneev, KV; Atretkhany, KN; Drutskaya, MS; Grivennikov, SI; Kuprash, DV; Nedospasov, SA (January 2017). "TLR-signaling and proinflammatory cytokines as drivers of tumorigenesis". Cytokine. 89: 127–135. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2016.01.021. PMID 26854213.

- ^ Sanwal, BD (March 1970). "Allosteric controls of amphilbolic pathways in bacteria". Bacteriol. Rev. 34 (1): 20–39. doi:10.1128/MMBR.34.1.20-39.1970. PMC 378347. PMID 4315011.

- ^ Jacob, F; Monod, J (June 1961). "Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins". J Mol Biol. 3 (3): 318–356. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(61)80072-7. PMID 13718526. S2CID 19804795.

- ^ CS Holling. "Resilience and stability of ecological systems". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4:1-23. 1973

- ^ Scheff, Thomas (2 September 2009). "The Emotional/Relational World". Psychology Today. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "The Study of Earth as an Integrated System". nasa.gov. NASA. 2016. Archived from the original on 2 November 2016.

- ^ Fig. TS.17, Technical Summary, Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), Working Group I, IPCC, 2021, p. 96. Archived from the original on 21 July 2022.

- ^ Stocker, Thomas F.; Dahe, Qin; Plattner, Gian-Kaksper (2013). IPCC AR5 WG1. Technical Summary (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2023. See esp. TFE.6: Climate Sensitivity and Feedbacks at p. 82.

- ^ A. I. Mees (c. 1981) Dynamics of Feedback Systems, New York: J. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-27822-X. p. 69: "There is a tradition in control theory that one deals with a negative feedback loop in which a negative sign is included in the feedback loop ..."

- ^ Araki, M., PID Control (PDF)

- ^ Minorsky, Nicolas (1922). "Directional stability of automatically steered bodies". Journal of the American Society for Naval Engineers. 34 (2): 280–309. doi:10.1111/j.1559-3584.1922.tb04958.x.

- ^

Wai-Kai Chen (2005). "Chapter 13: General feedback theory". Circuit Analysis and Feedback Amplifier Theory. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press. pp. 13.1–13.14. ISBN 9781420037272. 423825181.

[In a practical amplifier] the forward path may not be strictly unilateral, the feedback path is usually bilateral, and the input and output coupling networks are often complicated.

- ^

Santiram Kal (2009). Basic Electronics: Devices, Circuits and IT Fundamentals. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 191. ISBN 9788120319523.

If the feedback signal reduces the input signal, i.e. it is out of phase with the input [signal], it is called negative feedback.

- ^ With mechanical devices, hunting can be severe enough to destroy the device.

- ^ P. Horowitz & W. Hill, The Art of Electronics, Cambridge University Press (1980), Chapter 3, relating to operational amplifiers.

- ^

For an analysis of desensitization in the system pictured, see S.K Bhattacharya (2011). "§5.3.1 Effect of feedback on parameter variations". Linear Control Systems. Pearson Education India. pp. 134–135. ISBN 9788131759523.

The parameters of a system ... may vary... The primary advantage of using feedback in control systems is to reduce the system's sensitivity to parameter variations.

- ^ a b Snelgrove, Martin (2011). "Oscillator". McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, 10th Ed., Science Access online service. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d Chattopadhyay, D. (2006). Electronics (fundamentals And Applications). New Age International. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-81-224-1780-7.

- ^ Garg, Rakesh Kumar; Ashish Dixit; Pavan Yadav (2008). Basic Electronics. Firewall Media. p. 280. ISBN 978-8131803028.

- ^ Volnei A. Pedroni (2008). Digital electronics and design with VHDL. Morgan Kaufmann. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-12-374270-4.

- ^ Latches and Flip Flops Archived 5 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine (EE 42/100 Lecture 24 from Berkeley) "...Sometimes the terms flip-flop and latch are used interchangeably..."

- ^ H. Giese; Y. Brun; J. D. M. Serugendo; C. Gacek; H. Kienle; H. Müller; M. Pezzè; M. Shaw (2009). "Engineering self-adaptive and self-managing systems". Springer-Verlag.

- ^ J. L. Hellerstein; Y. Diao; S. Parekh; D. M. Tilbury (2004). Feedback Control of Computing Systems. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ J. O. Kephart; D. M. Chess (2003). "The vision of autonomic computing".

- ^ H. A. Müller; H. M. Kienle & U. Stege (2009). "Autonomic computing: Now you see it, now you don't—design and evolution of autonomic software systems".

- ^ Hofstadter, Douglas (2007). I Am a Strange loop. New York: Basic Books. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-465-03079-8.

Further reading

- Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play. MIT Press. 2004. ISBN 0-262-24045-9. Chapter 18: Games as Cybernetic Systems.

- Korotayev A., Malkov A., Khaltourina D. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Secular Cycles and Millennial Trends. Moscow: URSS, 2006. ISBN 5-484-00559-0

- Dijk, E., Cremer, D.D., Mulder, L.B., and Stouten, J. "How Do We React to Feedback in Social Dilemmas?" In Biel, Eek, Garling & Gustafsson, (eds.), New Issues and Paradigms in Research on Social Dilemmas, New York: Springer, 2008.

External links

Media related to Feedback at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Feedback at Wikimedia Commons

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use dmy dates from March 2023

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2014

- Articles to be expanded from September 2020

- All articles to be expanded

- Articles with empty sections from September 2020

- All articles with empty sections

- Articles using small message boxes

- Commons category link from Wikidata

- Feedback

- Control theory

- Management cybernetics

- Electronic feedback

- Broad-concept articles