Dwarfism

| Dwarfism | |

|---|---|

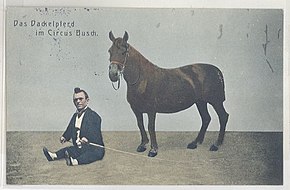

| Other names: Restricted growth, dwarf, little person (LP), person of short stature | |

| |

| A man in Columbus, Indiana, with dwarfism caused by achondroplasia | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology, medical genetics |

| Types | Proportionate, disproportionate[1] |

| Causes | Short parents, growth hormone deficiency, genetic disorders[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Height < 147 centimetres (4 ft 10 in)[2] |

| Treatment | Based on the cause[3] |

| Medication | Growth hormone therapy[3] |

| Prognosis | Generally normal life expectancy[2] |

| Frequency | ~2.5% (USA)[4] |

Dwarfism is when an person is exceptionally short.[1] This is sometimes defined as an adult height of less than 147 centimetres (4 ft 10 in).[2] There are two main types: disproportionate dwarfism with short limbs and proportionate dwarfism with both short limbs and torso.[1] Intelligence is usually normal, as is life expectancy.[2] Other symptoms may depend on the underlying cause.[5]

The most common cause of proportionate dwarfism is having short parents; though it may also occur due to growth hormone deficiency, Turner syndrome, and other genetic conditions.[1] Disproportionate dwarfism is most commonly due to achondroplasia.[1] More than 300 conditions can result in dwarfism.[2] Diagnosis may occur before, at, or some time after birth.[1]

Treatment depends on the underlying cause.[3] Those with growth hormone deficiency and certain other conditions may be treated with growth hormone therapy.[3] In cases with particularly short legs, surgery to lengthen them may be carried out, though this is generally not recommended.[3][4] Other measures may include physiotherapy and modification of the persons environment.[3][6] Women with disproportionate disease who become pregnant generally require cesarean delivery.[7]

Dwarfism affects about 2.5% of people in the United States.[4] Most people prefer the use of their name; though terms such as "little person" (LP), "person of short stature", or "dwarf" may be used.[8] Historically, the term "midget" was used; however, this term is now often regarded as offensive.[9][7] Those affected may face height discrimination and bullying.[7] Support groups may provide services and resources.[10]

Signs and symptoms

A defining characteristic of dwarfism is an adult height less than the 2.3rd percentile of the CDC standard growth charts.[11] The average adult height among people with dwarfism is 122 centimetres (4 ft 0 in).[12][13] There is a wide range of physical characteristics. Variations in individuals are identified by diagnosing and monitoring the underlying disorders. There may not be any complications outside adapting to their size.

Short stature is a common replacement of the term 'dwarfism', especially in a medical context. Short stature is clinically defined as a height within the lowest 2.3% of those in the general population. However, those with mild skeletal dysplasias may not be affected by dwarfism. In some cases of untreated hypochondroplasia, males grow up to 165 cm (5 feet 5 inches). Though that is short in a relative context, it does not fall into the extreme ranges of the growth charts.

Disproportionate dwarfism is characterized by shortened limbs or a shortened torso. In achondroplasia one has an average-sized trunk with short limbs and a larger forehead.[14] Facial features are often affected and individual body parts may have problems associated with them. Spinal stenosis, ear infection, and hydrocephalus are common. In case of spinal dysostosis, one has a small trunk, with average-sized limbs.

Proportionate dwarfism is marked by a short torso with short limbs,[15] thus leading to a height that is significantly below average. There may be long periods without any significant growth. Sexual development is often delayed or impaired into adulthood. This dwarfism type is caused by an endocrine disorder and not a skeletal dysplasia.

Physical effects of malformed bones vary according to the specific disease. Many involve joint pain caused by abnormal bone alignment, or from nerve compression.[16] Early degenerative joint disease, exaggerated lordosis or scoliosis, and constriction of spinal cord or nerve roots can cause pain and disability.[17] Reduced thoracic size can restrict lung growth and reduce pulmonary function. Some forms of dwarfism are associated with disordered function of other organs, such as the brain or liver, sometimes severely enough to be more of an impairment than the unusual bone growth.[18][19]

Mental effects also vary according to the specific underlying syndrome. In most cases of skeletal dysplasia, such as achondroplasia, mental function is not impaired.[15] However, there are syndromes which can affect the cranial structure and growth of the brain, severely impairing mental capacity. Unless the brain is directly affected by the underlying disorder, there is little to no chance of mental impairment that can be attributed to dwarfism.[20]

The psycho-social limitations of society may be more disabling than the physical symptoms, especially in childhood and adolescence, but people with dwarfism vary greatly in the degree to which social participation and emotional health are affected.

- Social prejudice against extreme shortness may reduce social and marital opportunities.[21][22]

- Numerous studies have demonstrated reduced employment opportunities. Severe shortness is associated with lower income.[22]

- Self-esteem may suffer and family relationships may be affected.

- Extreme shortness (in the 60–90 cm or 2–3 feet range) can, if not accommodated for, interfere with activities of daily living, like driving or using countertops built for taller people. Other common attributes of dwarfism such as bowed knees and unusually short fingers can lead to back problems and difficulty in walking and handling objects.

- Children with dwarfism are particularly vulnerable to teasing and ridicule from classmates. Because dwarfism is relatively uncommon, children may feel isolated from their peers.[18]

Causes

Dwarfism can result from many medical conditions, each with its own separate symptoms and causes. Extreme shortness in humans with proportional body parts usually has a hormonal cause, such as growth-hormone deficiency, once called pituitary dwarfism.[16][14] Achondroplasia is responsible for the majority of human dwarfism cases, followed by spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia and diastrophic dysplasia.[24]

Achondroplasia

The most recognizable and most common form of dwarfism in humans is achondroplasia, which accounts for 70% of dwarfism cases, and occurs in 4 to 15 out of 100,000 live births.[25]

It produces rhizomelic short limbs, increased spinal curvature, and distortion of skull growth. In achondroplasia the body's limbs are proportionately shorter than the trunk (abdominal area), with a larger head than average and characteristic facial features. Achondroplasia is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by the presence of an altered allele in the genome. If a pair of achondroplasia alleles are present, the result is fatal. Achondroplasia is a mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3.[26] In the context of achondroplasia, this mutation causes FGFR3 to become constitutively active, inhibiting bone growth.[27]

Growth hormone deficiency

Growth hormone deficiency (GHD) is a medical condition in which the body produces insufficient growth hormone. Growth hormone, also called somatotropin, is a polypeptide hormone which stimulates growth and cell reproduction. If this hormone is lacking, stunted or even halted growth may become apparent. Children with this disorder may grow slowly and puberty may be delayed by several years or indefinitely. Growth hormone deficiency has no single definite cause. It can be caused by mutations of specific genes, damage to the pituitary gland, Turner's syndrome, poor nutrition,[28] or even stress (leading to psychogenic dwarfism). Laron syndrome (growth hormone insensitivity) is another cause. Those with growth hormone issues tend to be proportionate.

Other

Other causes of dwarfism are spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita, diastrophic dysplasia, pseudoachondroplasia, hypochondroplasia, Noonan syndrome, primordial dwarfism, Cockayne syndrome, Turner syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), and hypothyroidism. Severe shortness with skeletal distortion also occurs in several of the Mucopolysaccharidoses and other storage disorders.[29] Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism may cause proportionate, yet temporary, dwarfism. NPR2 disproportionate dwarfism was discovered recently and is caused by a mutant gene.[30]

Serious chronic illnesses may produce dwarfism as a side effect. Harsh environmental conditions, such as malnutrition, may also produce dwarfism. These types of dwarfism are indirect consequences of the generally unhealthy or malnourished condition of the individual, and not of any specific disease. The dwarfism often takes the form of simple short stature, without any deformities, thus leading to proportionate dwarfism. In societies where poor nutrition is widespread, the average height of the population may be reduced below its genetic potential by the lack of proper nutrition. Sometimes there is no definitive cause of short stature.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

Dwarfism is often diagnosed in childhood on the basis of visible symptoms. A physical examination can usually suffice to diagnose certain types of dwarfism, but genetic testing and diagnostic imaging may be used to determine the exact condition.[31] In a person's youth, growth charts that track height can be used to diagnose subtle forms of dwarfism that have no other striking physical characteristics.[24]

Short stature or stunted growth during youth is usually what brings the condition to medical attention. Skeletal dysplasia is usually suspected because of obvious physical features (e.g., unusual configuration of face or shape of skull), because of an obviously affected parent, or because body measurements (arm span, upper to lower segment ratio) indicate disproportion.[31] Bone X-rays are often key to diagnosing a specific skeletal dysplasia, but are not the sole diagnostic tool. Most children with suspected skeletal dysplasias are referred to a genetics clinic for diagnostic confirmation and genetic counseling. Since about the year 2000, genetic tests for some of the specific disorders have become available.[32]

During an initial medical evaluation of shortness, the absence of disproportion and other clues listed above usually indicates causes other than bone dysplasias.

Classification

In men and women, the sole requirement for being considered a dwarf is having an adult height under 147 cm (4 ft 10 in) and it is almost always sub-classified with respect to the underlying condition that is the cause of the short stature. Dwarfism is usually caused by a genetic variant; achondroplasia is caused by a mutation on chromosome 4. If dwarfism is caused by a medical disorder, the person is referred to by the underlying diagnosed disorder. Disorders causing dwarfism are often classified by proportionality. Disproportionate dwarfism describes disorders that cause unusual proportions of the body parts, while proportionate dwarfism results in a generally uniform stunting of the body.

Disorders that cause dwarfism may be classified according to one of hundreds of names, which are usually permutations of the following roots:

- location

- rhizomelic = root, i.e., bones of the upper arm or thigh

- mesomelic = middle, i.e., bones of the forearm or lower leg

- acromelic = end, i.e., bones of hands and feet.

- micromelic = entire limbs are shortened

- source

- chondro = of cartilage

- osteo = of bone

- spondylo = of the vertebrae

- plasia = form

- trophy = growth

Examples include achondroplasia and chondrodystrophy.

Prevention

Many types of dwarfism are currently impossible to prevent because they are genetically caused. Genetic conditions that cause dwarfism may be identified with genetic testing, by screening for the specific variations that result in the condition. However, due to the number of causes of dwarfism, it may be impossible to determine definitively if a child will be born with dwarfism.

Dwarfism resulting from malnutrition or a hormonal abnormality may be treated with an appropriate diet or hormonal therapy. Growth hormone deficiency may be remedied via injections of human growth hormone (HGH) during early life.[33]

Management

Genetic mutations of most forms of dwarfism caused by bone dysplasia cannot be altered yet, so therapeutic interventions are typically aimed at preventing or reducing pain or physical disability, increasing adult height, or mitigating psychosocial stresses and enhancing social adaptation.[34]

Forms of dwarfism associated with the endocrine system may be treated using hormonal therapy. If the cause is prepubescent hyposecretion of growth hormone, supplemental growth hormone may correct the abnormality. If the receptor for growth hormone is itself affected, the condition may prove harder to treat. Hypothyroidism is another possible cause of dwarfism that can be treated through hormonal therapy. Injections of thyroid hormone can mitigate the effects of the condition, but lack of proportion may be permanent.

Pain and disability may be ameliorated by physical therapy, braces or other orthotic devices, or by surgical procedures.[34] The only simple interventions that increase perceived adult height are dress enhancements, such as shoe lifts or hairstyle. Growth hormone is rarely used for shortness caused by bone dysplasias, since the height benefit is typically small (less than 5 cm [2 in]) and the cost high.[35] The most effective means of increasing adult height by several inches is distraction osteogenesis, though availability is limited and the cost is high in terms of money, discomfort, and disruption of life. Most people with dwarfism do not choose this option, and it remains controversial.[16] For other types of dwarfism, surgical treatment is not possible.

Society and culture

Terminology

The appropriate term for describing a person of particularly short stature (or with the genetic condition achondroplasia) has developed euphemistically.

The noun dwarf stems from Old English dweorg, originally referring to a being from Germanic mythology—a dwarf—that dwells in mountains and in the earth, and is associated with wisdom, smithing, mining, and crafting. The etymology of the word dwarf is contested, and scholars have proposed varying theories about the origins of the being, including that dwarfs may have originated as nature spirits or as beings associated with death, or as a mixture of concepts. Competing etymologies include a basis in the Indo-European root *dheur- (meaning 'damage'), the Indo-European root *dhreugh (whence modern German Traum 'dream' and Trug 'deception'), and comparisons have been made with the Old Indian dhvaras (a type of demonic being). The being may not have gained associations with small stature until a later period.[36]

The terms "dwarf", "little person", "LP", and "person of short stature" are now generally considered acceptable by most people affected by these disorders.[14] However, the plural "dwarfs" as opposed to "dwarves" is generally preferred in the medical context, possibly because the plural "dwarves" was popularized by author J. R. R. Tolkien, describing a race of characters in his The Lord of the Rings books resembling Norse dwarfs.[37]

"Midget", whose etymology indicates a "tiny biting insect",[38] came into prominence in the mid-19th century after Harriet Beecher Stowe used it in her novels Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands and Oldtown Folks where she described children and an extremely short man, respectively.[14] Later some people of short stature considered the word to be offensive because it was the descriptive term applied to P. T. Barnum's dwarfs used for public amusement during the freak show era.[16][39] It is also not considered accurate as it is not a medical term or diagnosis, though it is sometimes used as a slang term to describe those who are particularly short, whether or not they have dwarfism.[40]

Sports

Dwarfs are supported to compete in sport by a number of organisations nationally and internationally.

Dwarfs are included in some events in the Athletics at the Summer Paralympics.

The Dwarf Athletic Association of America and the Dwarf Sports Association UK provide opportunities for dwarfs to compete nationally and internationally in the Americas and Europe, respectively.

The Dwarf Sports Association UK organises between 5 and 20 events per month for athletes with restricted growth conditions in the UK.[41]

For instance, swimming and bicycling are often recommended for people with skeletal dysplasias, since those activities put minimal pressure on the spine.[42]

Since its early days, professional wrestling has had the involvement of dwarf athletes. "Midget wrestling" had its heyday in the 1950s–'70s, when wrestlers such as Little Beaver, Lord Littlebrook, and Fuzzy Cupid toured North America, and Sky Low Low was the first holder of the National Wrestling Alliance's World Midget Championship. In the following couple of decades, more wrestlers became prominent in North America, including foreign wrestlers like Japan's Little Tokyo. Although the term is seen by some as pejorative, many past and current midget wrestlers, including Hornswoggle, have said they take pride in the term due to its history in the industry and its marketability.[citation needed]

Art and media

In art, literature, and movies, dwarfs are rarely depicted as ordinary people who are very short but rather as a species apart. Novelists, artists, and moviemakers may attach special moral or aesthetic significance to their "apartness" or misshapenness.

Artistic representations of dwarfism can be found on Greek vases and other ancient artifacts, including ancient Egyptian art in which dwarfs are likely to have been seen as a divine manifestation, with records indicating they could reach high positions in society.[43][44]

The Bhagavat Purana Hindu text devotes nine chapters to the adventures of Vamana, a dwarf avatar of Lord Vishnu.

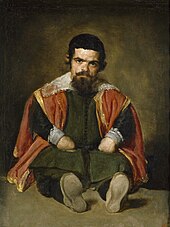

Depictions of dwarfism are also found in European paintings and many illustrations. Many European paintings (especially Spanish) of the 16th–19th centuries depict dwarfs by themselves or with others. In the Talmud, it is said that the second born son of the Egyptian Pharaoh of the Bible was a dwarf.[45] Recent scholarship has suggested that ancient Egyptians held dwarfs in high esteem.[46] Several important mythological figures of the North American Wyandot nation are portrayed as dwarfs.[47]

As popular media have become more widespread, the number of works depicting dwarfs have increased dramatically. Dwarfism is depicted in many books, films, and TV series such as Willow, The Wild Wild West, The Man with the Golden Gun (and later parodied in Austin Powers), Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift,[48] The Wizard of Oz, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, Bad Santa, A Son of the Circus, Little People, Big World, The Little Couple, A Song of Ice and Fire (and its TV adaptation Game of Thrones), Seinfeld, The Orator, In Bruges, The Tin Drum by Günter Grass, the short-lived reality show The Littlest Groom, and the films The Station Agent and Zero.

The Animal Planet TV series Pit Boss features dwarf actor Shorty Rossi and his talent agency, "Shortywood Productions", which Rossi uses to provide funding for his pit bull rescue operation, "Shorty's Rescue". Rossi's three full-time employees, featured in the series, are all little people and aspiring actors.

In September 2014, Creative Business House, along with Donnons Leur Une Chance, created the International Dwarf Fashion Show to raise awareness and boost self-confidence of people living with dwarfism.[49]

A number of reality television series on Lifetime, beginning with Little Women: LA in 2014, focused on showing the lives of women living with dwarfism in various cities around the United States.

See also

- Dwarf-tossing

- Ellis–Van Creveld syndrome

- Gigantism

- Kingdom of the Little People

- Laron syndrome

- List of people with dwarfism

- List of dwarfism organisations

- List of shortest people

- Mulibrey nanism

- Our Little Life (reality television show)

- Phyletic dwarfism

- Pygmy peoples

- Dwarf hamster (disambiguation)

- Dwarf rabbit

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Restricted growth (dwarfism)". nhs.uk. 23 October 2017. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "MedlinePlus: Dwarfism". MedlinePlus. National Institute of Health. 2008-08-04. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2008-10-03.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 "Restricted growth (dwarfism) - Treatment". nhs.uk. 21 February 2018. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Jain, Megha; Saber, Ahmed Y. (2022). "Dwarfism". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ↑ "Restricted growth (dwarfism) - Symptoms". nhs.uk. 21 February 2018. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ↑ "A Guide To Home Modifications". www.lpaonline.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Dwarfism - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ↑ "FAQ". www.lpaonline.org. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ↑ "Definition of MIDGET". Merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 2017-11-14. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ↑ "Dwarfism - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ↑ "CDC standard growth charts". Archived from the original on 2016-10-09. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ↑ "FAQ". Lpaonline.org. Archived from the original on 2017-05-07. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ↑ Pauli, RM; Adam, MP; Ardinger, HH; Pagon, RA; Wallace, SE; Bean, LJH; Mefford, HC; Stephens, K; Amemiya, A; Ledbetter, N (2012). "Achondroplasia". GeneReviews. PMID 20301331.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Kennedy, Dan. "P.O.V. – Big Enough. What is Dwarfism?". Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on 2009-03-13. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Dwarfism: Symptoms". MayoClinic.com. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Archived from the original on 2009-02-13. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "Dwarfism Resources: Frequently Asked Questions". Little People of America. 2006-07-09. Archived from the original on 2006-05-16. Retrieved 2006-11-14.

- ↑ "Dwarfism and Bone Dysplasias". Seattle Children's Hospital, Research & Foundation. Archived from the original on 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Dwarfism: Complications". MayoClinic.com. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Archived from the original on 2008-12-20. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ Escamilla RF, Hutchings JJ, Li CH, Forsham P (August 1966). "Achondroplastic dwarfism. Effects of treatment with human growth hormone". Calif Med. 105 (2): 104–10. PMC 1516352. PMID 5946547.

- ↑ "The Pituitary Gland & Growth Disorders: An Overview". Archived from the original on 2013-02-10. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ↑ Hall, Judith A.; Adelson, Betty M. (2005). Dwarfism: medical and psychosocial aspects of profound short stature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8121-8.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Gollust SE, Thompson RE, Gooding HC, Biesecker BB (August 2003). "Living with achondroplasia in an average-sized world: an assessment of quality of life". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 120A (4): 447–58. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.20127. PMID 12884421. S2CID 38614817.

- ↑ Ancient Egypt: Kingdom of the Pharaohs, R. Hamilton, p. 47, Paragon, 2006, ISBN 1-4054-8288-5

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Dwarfism". KidsHealth. Archived from the original on 2015-07-04. Retrieved 2015-06-30.

- ↑ Çevik, Banu; Çolakoğlu, Serhan (2010). "Anesthetic management of achondroplastic dwarf undergoing cesarean section" (PDF). M.E.J. Anesth. 20 (6). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2018.

- ↑ FGFR3

- ↑ "Achondroplasia – Genetics Home Reference". Genetics Home Reference. National Institute of Health. 2008-09-26. Archived from the original on 2008-12-04. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- ↑ "Growth Hormone Deficiency". UK Child Growth Foundation. Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ↑ "Causes of Dwarfism". WrongDiagnosis.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ A Loss-of-Function Mutation in Natriuretic Peptide Receptor 2 (Npr2) Gene Is Responsible for Disproportionate Dwarfism in cn/cn Mouse* (https://www.jbc.org/article/S0021-9258(19)60512-0/pdf)[permanent dead link]

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "DWARFISM (Algorithmic Diagnosis of Symptoms and Signs) - WrongDiagnosis.com". Archived from the original on 2019-12-12. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ↑ "Dwarfism: Tests and diagnosis". Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. 2007-08-27. Archived from the original on 2008-12-20. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ Jørgensen, Jens O.L.; Christiansen, Jens S. (2005), "Clinical Aspects of Growth Hormone Deficiency in Adults", Growth Hormone Deficiency in Adults, KARGER, vol. 33, pp. 1–20, doi:10.1159/000088338, ISBN 3-8055-7992-6, PMID 16166752

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Dwarfism: Treatment and drugs". MayoClinic.com. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. 2007-09-27. Archived from the original on 2008-12-20. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ Hagenäs L, Hertel T (2003). "Skeletal dysplasia, growth hormone treatment and body proportion: comparison with other syndromic and non-syndromic short children". Horm. Res. 60 Suppl 3 (3): 65–70. doi:10.1159/000074504. PMID 14671400. S2CID 29174195. Archived from the original on 2011-11-22. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ↑ Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology, pp. 67–68. D.S. Brewer ISBN 0-85991-513-1

- ↑ Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (1955). The Return of the King. George Allen & Unwin. pp. Appendix F. Archived from the original on 2019-11-15. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ↑ "midget". Online Etymology Dictionary. Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ Adelson, Betty M. (2005). The Lives Of Dwarfs: Their Journey From Public Curiosity Toward Social Liberation. Rutgers University Press. p. 295. ISBN 9780813535487. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ "Midget definition". MedicineNet. MedicineNet, Inc. 9 March 2003. Archived from the original on 2011-06-23. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ "DSAuk Events". Dsauk.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- ↑ Philadelphia, The Children's Hospital of (25 March 2014). "Skeletal Dysplasias". Chop.edu. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ↑ Ancient Egyptian Medicine, John F. Nunn, University of Oklahoma Press, 2002, pp. 78–79, ISBN 0-8061-3504-2

- ↑ "Dwarfs Commanded Respect In Ancient Egypt". Sciencedaily.com. Archived from the original on 2017-09-01. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ↑ The Talmud – Chapter VI. Death Of Jacob And His Sons – Moses – The Deliverance From Egypt. Archived 2016-05-20 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed April 23, 2007.

- ↑ Kozma, Chahira (2005-12-27). "Dwarfs in ancient Egypt". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 140A (4): 303–11. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31068. PMID 16380966. S2CID 797288. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- ↑ Trigger, Bruce G., The Children of Aataentsic: A History of the Huron People to 1660 McGill-Queen's University Press, 1987 ISBN 0-7735-0627-6, p. 529.

- ↑ Gulliver's Travels: Complete, Authoritative Text with Biographical and Historical Contexts, Palgrave Macmillan 1995 (p. 21). The quote has been misattributed to Alexander Pope, who wrote to Swift in praise of the book just a day earlier.

- ↑ Stark, Stephanie. "The Dwarf Fashion Show Debuts in New York City". Glammonitor. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Look up dwarf in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Little People of the World Organization Archived 2021-05-10 at the Wayback Machine [Hub for all International Organizations; services/advocacy/know your rights/support]

- Little People of America Archived 2021-05-07 at the Wayback Machine (Includes a list of International support groups)

- Little People of Canada Archived 2021-05-05 at the Wayback Machine (Includes a list of Canadian Provincial support groups)

- Little People UK Archived 2022-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Dwarf Sports Association UK Archived 2022-01-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Restricted Growth Association UK Archived 2022-01-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Pages with script errors

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from March 2022

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with permanently dead external links

- CS1: long volume value

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2020

- Dwarfism

- Growth disorders

- Human height

- RTT