Warfarin necrosis

| Warfarin necrosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Anticoagulant-induced skin necrosis | |

| |

| Right leg affected by warfarin necrosis. | |

| Symptoms | Well defined fragile skin which blisters and diesFemales>males[1] |

| Usual onset | First week of warfarin treatment[1] |

| Causes | Acquired protein C deficiency following warfarinFemales>males[1] |

| Risk factors | Obesity[1] |

| Frequency | Females>males[1] |

Warfarin necrosis is death of skin and subcutaneous tissue due to acquired protein C deficiency following treatment with anti-vitamin K anticoagulants (4-hydroxycoumarins, such as warfarin).[1] Initial symptoms are areas of skin pain and redness, which develop a sharp border and become petechial, then hard and purpuric.[2]: 122 They may then resolve or progress to form large, irregular, bloody bullae with eventual necrosis and slow-healing eschar formation. Commonly affected sites are breasts, thighs, buttocks and penis, all areas with subcutaneous fat.[2]: 122

Development of the syndrome is associated with the use of large loading doses at the start of treatment.[1] In rare cases, the fascia and muscle are involved.[3] Risk factors include obesity.[2]

Warfarin necrosis is a rare but severe complication of treatment with warfarin or related anticoagulants.[4] It typically occurs in middle aged, with female affected three times more often than males.[2]: 122–3 This drug eruption usually occurs between the third and tenth days of therapy with warfarin derivatives.[5]

Mechanism

Warfarin necrosis usually occurs three to five days after drug therapy is begun, and a high initial dose increases the risk of its development.[2]: 122 Warfarin-induced necrosis can develop both at sites of local injection and - when infused intravenously - in a widespread pattern.[2]: 123

In warfarin's initial stages of action, inhibition of protein C and Factor VII is stronger than inhibition of the other vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors II, IX, and X. This results from the fact that these proteins have different half-lives: 1.5 to six hours for factor VII and eight hours for protein C, versus one day for factor IX, two days for factor X and two to five days for factor II. The larger the initial dose of vitamin K-antagonist, the more pronounced these differences are. This coagulation factor imbalance leads to paradoxical activation of coagulation, resulting in a hypercoagulable state and thrombosis. The blood clots interrupt the blood supply to the skin, causing necrosis. Protein C is an innate anticoagulant, and as warfarin further decreases protein C levels, it can lead to massive thrombosis with necrosis and gangrene of limbs.

Notably, the prothrombin time (or international normalized ratio, INR) used to test the effect of warfarin is highly dependent on factor VII, which explains why patients can have a therapeutic INR (indicating good anticoagulant effect) but still be in a hypercoagulable state.[5]

In one third of cases, warfarin necrosis occurs in patients with an underlying, innate and previously unknown deficiency of protein C. The condition is related to purpura fulminans, a complication in infants with sepsis which also involves skin necrosis. These infants often have protein C deficiency as well. There have also been cases in patients with other deficiency, including protein S deficiency,[6][7] activated protein C resistance (Factor V Leiden)[8] and antithrombin III deficiency.[9]

Although the above hypothesis is the most commonly accepted, others believe that it is a hypersensitivity reaction or a direct toxic effect.[5]

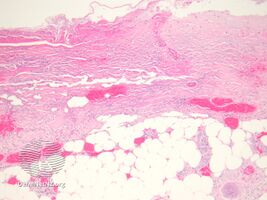

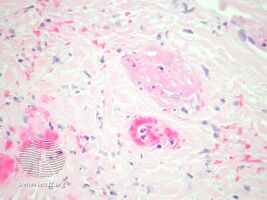

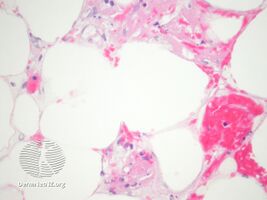

Diagnosis

-

Warfarin necrosis

-

Warfarin necrosis

-

Warfarin necrosis

Differential diagnosis

Many conditions mimic or may be mistaken for warfarin necrosis, including pyoderma gangrenosum or necrotizing fasciitis. Warfarin necrosis is also different from another drug eruption associated with warfarin, purple toe syndrome, which usually occurs three to eight weeks after the start of anticoagulation therapy. No report has described this disorder in the immediate postpartum period in patients with protein S deficiency.[10]

Prevention

Vitamin K1 can be used to reverse the effects of warfarin, and heparin or its low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) can be used in an attempt to prevent further clotting. None of these suggested therapies have been studied in clinical trials.

Heparin and LMWH act by a different mechanism than warfarin, so these drugs can also be used to prevent clotting during the first few days of warfarin therapy and thus prevent warfarin necrosis (this is called 'bridging').

Treatment

The first element of treatment is usually to discontinue the offending drug, although there have been reports describing how the eruption evolved little after it had established in spite of continuing the medication.[11][12]

Based on the assumption that low levels of protein C are involved in the underlying mechanism, common treatments in this setting include fresh frozen plasma or pure activated protein C.[13]

Since the clot-promoting effects of starting administration of 4-hydroxycoumarins are transitory, patients with protein C deficiency or previous warfarin necrosis can still be restarted on these drugs if appropriate measures are taken.[14] These include gradual increase starting from low doses and supplemental administration of protein C (pure or from fresh frozen plasma).[15]

The necrotic skin areas are treated as in other conditions, sometimes healing spontaneously with or without scarring, sometimes going on to require surgical debridement or skin grafting.[5]

History

While skin necrosis in patients had been previously described, Verhagen was the first to publish a paper on this relationship in the medical literature, in 1954.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "8. Vasculopathic reaction pattern". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ Schleicher SM, Fricker MP (April 1980). "Coumadin necrosis". Arch Dermatol. 116 (4): 444–5. doi:10.1001/archderm.116.4.444. PMID 7369776.

- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. pp. 331, 340. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 McKnight JT, Maxwell AJ, Anderson RL (1992). "Warfarin necrosis". Arch Fam Med. 1 (1): 105–8. doi:10.1001/archfami.1.1.105. PMID 1341581.

- ↑ Sallah S, Abdallah JM, Gagnon GA (1998). "Recurrent warfarin-induced skin necrosis in kindreds with protein S deficiency". Haemostasis. 28 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1159/000022380. PMID 9885367. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- ↑ Grimaudo V, Gueissaz F, Hauert J, Sarraj A, Kruithof EK, Bachmann F (January 1989). "Necrosis of skin induced by coumadin in a patient deficient in protein S". BMJ. 298 (6668): 233–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.298.6668.233. PMC 1835547. PMID 2522326.

- ↑ Makris M, Bardhan G, Preston FE (March 1996). "Warfarin induced skin necrosis associated with activated protein C resistance". Thromb. Haemost. 75 (3): 523–4. PMID 8701423.

- ↑ Kiehl R, Hellstern P, Wenzel E (January 1987). "Hereditary antithrombin III (AT III) deficiency and atypical localization of a coumadin necrosis". Thromb. Res. 45 (2): 191–3. doi:10.1016/0049-3848(87)90173-3. PMID 3563984.

- ↑ Cheng, A; Scheinfeld, NS; McDowell, B; Dokras, AA (1997). "Warfarin skin necrosis in a postpartum woman with protein S deficiency". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 90 (4 Pt 2): 671–2. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00393-1. PMID 11770590.

- ↑ Nalbandian RM, Mader IJ, Barrett JL, Pearce JF, Rupp EC (May 1965). "Petechiae, ecchymoses, and necrosis of skin induced by coumadin congeners: rare, occasionally lethal complication of anticoagulant therapy". JAMA. 192: 603–8. doi:10.1001/jama.1965.03080200021006. PMID 14284863.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Verhagen H (1954). "Local haemorrhage and necrosis of the skin and underlying tissues, during anti-coagulant therapy with dicumarol or dicumacyl". Acta Med Scand. 148 (6): 453–67. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1954.tb01741.x. PMID 13171021.

- ↑ Schramm W, Spannagl M, Bauer KA, et al. (June 1993). "Treatment of coumadin-induced skin necrosis with a monoclonal antibody purified protein C concentrate". Arch Dermatol. 129 (6): 753–6. doi:10.1001/archderm.129.6.753. PMID 8507079.

- ↑ Zauber NP, Stark MW (May 1986). "Successful warfarin anticoagulation despite protein C deficiency and a history of warfarin necrosis". Ann. Intern. Med. 104 (5): 659–60. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-104-5-659. PMID 3754407.

- ↑ De Stefano V, Mastrangelo S, Schwarz HP, et al. (August 1993). "Replacement therapy with a purified protein C concentrate during initiation of oral anticoagulation in severe protein C congenital deficiency". Thromb. Haemost. 70 (2): 247–9. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1649478. PMID 8236128.