Vertebral osteomyelitis

| Vertebral osteomyelitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Spinal osteomyelitis, Spondylodiskitis, or Disk-space infection,[1] | |

| |

| Numbering order of vertebrae of human spinal column | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Frequency | Lua error in Module:PrevalenceData at line 5: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

Vertebral osteomyelitis is a type of osteomyelitis (infection and inflammation of the bone and bone marrow) that affects the vertebrae. It is a rare bone infection concentrated in the vertebral column.[2] The infection can be classified as acute or chronic depending on the severity of the onset of the case,[3] where acute people often experience better outcomes than those living with the chronic symptoms that are characteristic of the disease. Although vertebral osteomyelitis is found in people across a wide range of ages, the infection is commonly reported in young children and older adults. Vertebral osteomyelitis often attacks two vertebrae and the corresponding intervertebral disk, causing narrowing of the disc space between the vertebrae.[4] The prognosis for the disease is dependent on where the infection is concentrated in the spine, the time between initial onset and treatment, and what approach is used to treat the disease.[5]

Signs and symptoms

The disease is known for its subtle onset in people, and few symptoms characterize vertebral osteomyelitis. Correct diagnosis of the disease is often delayed for an average of six to twelve weeks due to such vague, ambiguous symptoms.[4]

General Cases

General symptoms found in a cross-section of people with vertebral osteomyelitis include fever, swelling at the infection site, weakness of the vertebral column and surrounding muscles, and difficulty transitioning from a standing to a sitting position.[4][6]

Additionally, persistent back pain and muscle spasms may become so debilitating that they confine the person to a sedentary state, where even slight movement or jolting of the body results in excruciating pain. In children, the presence of vertebral osteomyelitis can be signaled by these symptoms, along with high-grade fevers and an increase in the body's leukocyte count.[4][6]

Advanced Cases

People with an advanced case may present some or none of the symptoms associated with general cases of vertebral osteomyelitis. [4][6]

Symptomatic signs vary in each person and depend on the severity of the case. Neurologic deficiency characterizes advanced, threatening cases of the disease. On average, 40% of people with an advanced case of vertebral osteomyelitis experience some type of neurological deficiency; this is a sign that the infection has been progressing for some time. In advanced cases, the untreated infection will attack the nervous system through the spinal cord which runs parallel to the vertebral column, placing the person at risk for paralysis of the extremities. Additionally, loss of the ability to move is a trademark symptom of neurologic problems in advanced cases of vertebral osteomyelitis. Any further signs of neurological deficit signal an advanced case of vertebral osteomyelitis that requires immediate intervention to prevent further threat to the spinal cord.[4][6]

Causes

A notable aspect of the disease is found in its ability to start anywhere in the body and spread to other regions through the bloodstream.[3]

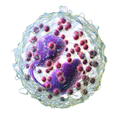

A number of bacterial strains can enter the body in this manner, making the origin of the infection hard to trace; thus, for many people with the infection, this characteristic can delay an accurate diagnosis and prolong suffering. The most common microorganism associated with vertebral osteomyelitis is the bacteria staphylococcus aureus. Another strain of staphylococcus aureus, commonly known as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), is a particularly harmful microorganism that is more difficult to treat than other related strains. Streptococcus equisimilis may also be responsible for the onset of vertebral osteomyelitis, though it is thought to be less virulent than staphylococcus aureus.[7][5][8][9]

-

Staphylococcus aureus, the most common microorganism associated with vertebral osteomyelitis

-

MRSA, a rare pathogen associated with some cases of vertebral osteomyelitis

Risk factors

The factors that can increase the possibility of initiating this condition are -diabetes, malnutrition, older age, prolonged use of corticosteroids and IV drug usage[5]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis is often complicated due to the delay between the onset of the disease and the initial display of symptoms. Before pursuing radiological methods of testing, physicians often order a full blood test to see how the persons levels compare to normal blood levels in a healthy body.[3]

In a complete blood test, the C-reactive protein (CRP) is an indicator of infection levels, the complete blood count (CBC) evaluates the presence of white and red blood cells, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) tests for inflammation in the body. Anomalous values that lie outside the acceptable ranges in any of these subcategories confirm the presence of infection in the body and indicate that further diagnostic measures are necessary. Blood tests may prove inconclusive and may not serve as enough evidence to confirm the presence of vertebral osteomyelitis. Diagnosis can also be complicated due to the disease's similarity to discitis, commonly known as an infection of the disc space. Both diseases are characterized by a person's inability to walk and concentrated back pain; however, people with vertebral osteomyelitis often appear more ill than those with discitis.[10] Additional measures may be called upon to rule out the possibility of discitis; such approaches include diagnosing the disease through various medical imaging techniques.[5][11]

Differential diagnosis

The DDx for this condition is based on the following:[5]

- Sickle cell anemia

- Gout

- Gaucher disease

- Sickle cell anemia

- Vitamin C deficiency

Radiological Diagnosis

Plain-film radiological orders are necessary for all people displaying symptoms of the disease; this diagnostic approach is often preliminary to other radiological procedures, such as magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography (CT) scan, fine-needle aspiration biopsy[5]. The initial plain-film X-ray images are scanned for any indication of disc compression between two vertebrae or the degeneration of one or more vertebrae. MRI scans do not expose the person to radiation and are highly sensitive to changes in the size and appearance of the intervertebral discs. If MRI imaging is inconclusive, the high sensitivity to erosions in the vertebrae or intervertebral discs of CT scans may be preferred for their ability to indicate signs of the disease more clearly than MRI. Additional tests may be ordered if such preliminary tests cannot confirm a diagnosis, for example, needle biopsies may be needed to take samples of bone surrounding the disc space where the infection is thought to live[12][13][5]

-

CT scan

-

MRI

Treatment

Nonsurgical intervention

Nonsurgical intervention is often desired because it possesses less risk to the body of further infection that can occur if the body is unnecessarily exposed to other outside pathogens during surgery. Intravaneous antibiotics may be prescribed to kill the microorganism causing the infection. Such antibiotics are administered at a continuous rate for a varying amount of time, lasting from four weeks to several months. The outcome for people who undergo intravaneous infusion differs according to factors such as age, strength of the immune system, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); if intervention through antibiotics fails, people are directed toward surgical treatment options.[14][5][15]

Surgical intervention

Surgery may be required for people with advanced cases of vertebral osteomyelitis. Spinal fusion is a common approach to destroying the microorganism causing the disease and rebuilding parts of the spine that were lost due to the infection. Fusions can be approached anteriorly or posteriorly, depending on where the infection is located in the vertebral area; spinal fusions involve cleaning the infected area of the spine and inserting instrumentation to stabilize the vertebrae and disc(s).[16][5][17]

Such instrumentation often includes bone grafts harvested from other areas of the body or from a bone bank, where bone fragments are harvested from deceased donors.[18]

The new bone graft is secured in the appropriate spinal region through the use of supporting rods and screws, most of which are made from titanium. Rods of this material promote healing and fusion of the bones more efficiently than stainless steel rods and are also more visible on MRI.[19]

Prognosis

Mortality rates are known to be higher in people whose infection is due to the bacteria staphylococcus aureus. However, if diagnosed quickly and treated correctly, people with staphylococcus aureus experience better outcomes than those with the disease caused by other microorganisms. The subtle progression of vertebral osteomyelitis places people at risk for paralysis, especially if the infection is concentrated in the thoracic or cervical vertebrae.[4][20]

Prevalence

In terms of the epidemiology of this condition, one finds that in the U.S. it is 4.8 cases/100,000 and worldwide we find it to be 1-7 cases/100,000[5]

Males have a greater incidence than females, additionally general disease incidence increases with age.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Zimmerli, Werner (18 March 2010). "Vertebral Osteomyelitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (11): 1022–1029. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0910753. PMID 20237348.

- ↑ Carek, Peter; Lori Dickerson; Jonathan Sack (15 June 2001). "Diagnosis and Management of Osteomyelitis". American Family Physician. 12 (63): 2413–2421. PMID 11430456. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 David Dugdale III; Jatin Vyas (2010). A.D.A.M Medical Encyclopedia: Osteomyelitis. Bethesda, MD: United States National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Wheeless III, Clifford (2011). Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics. Duke University: Data Trace. Archived from the original on 2020-09-22. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Graeber, Adam; Cecava, Nathan D. (2021). "Vertebral Osteomyelitis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Eren Gök, S.; Kaptanoğlu, E.; Celikbaş, A.; Ergönül, O.; Baykam, N.; Eroğlu, M.; Dokuzoğuz, B. (October 2014). "Vertebral osteomyelitis: clinical features and diagnosis". Clinical Microbiology and Infection: The Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 20 (10): 1055–1060. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12653. ISSN 1469-0691. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Jung, N.; Ernst, A.; Joost, I.; Yagdiran, A.; Peyerl-Hoffmann, G.; Grau, S.; Breuninger, M.; Hellmich, M.; Kubosch, D. C.; Klingler, J. H.; Seifert, H.; Kern, W. V.; Kaasch, A. J.; Rieg, S. (1 September 2021). "Vertebral osteomyelitis in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection: Evaluation of risk factors for treatment failure". Journal of Infection. 83 (3): 314–320. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.06.010. ISSN 0163-4453. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ↑ "Spinal Infection – Causes, Symptoms and Treatments". www.aans.org. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ↑ Krishnakumar, R.; Renjitkumar, J. (December 2012). "Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Vertebral Osteomyelitis Following Epidural Catheterization: A Case Report and Literature Review". Global Spine Journal. 2 (4): 231–234. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1329885. ISSN 2192-5682. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ↑ National Center for Biotechnology Information (October 2000). "Discitis versus Vertebral Osteomyelitis". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 83 (4): 368. doi:10.1136/adc.83.4.368. PMC 1718514. PMID 10999882.

- ↑ Roth, Annabelle; Chuard, Christian (9 October 2019). "[Vertebral osteomyelitis in adults]". Revue Medicale Suisse. 15 (666): 1818–1822. ISSN 1660-9379. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ↑ Garg, Vasant; Kosmas, Christos; Young, Peter C.; Togaru, Uday Kiran; Robbin, Mark R. (August 2014). "Computed tomography-guided percutaneous biopsy for vertebral osteomyelitis: a department's experience". Neurosurgical Focus. 37 (2): E10. doi:10.3171/2014.6.FOCUS14134. ISSN 1092-0684. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ↑ Benzel, Edward C. (2005). Spine Surgery: Techniques, Complication Avoidance, and Management. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 1720. ISBN 978-0-443-06616-0. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ↑ Oh, Won Sup; Moon, Chisook; Chung, Jin Won; Choo, Eun Ju; Kwak, Yee Gyung; Kim, Si-Hyun; Ryu, Seong Yeol; Park, Seong Yeon; Kim, Baek-Nam (2019). "Antibiotic Treatment of Vertebral Osteomyelitis caused by Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus: A Focus on the Use of Oral β-lactams". Infection & Chemotherapy. 51 (3): 284–294. doi:10.3947/ic.2019.51.3.284. ISSN 2093-2340. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ Babouee Flury, Baharak; Elzi, Luigia; Kolbe, Marko; Frei, Reno; Weisser, Maja; Schären, Stefan; Widmer, Andreas F; Battegay, Manuel (27 April 2014). "Is switching to an oral antibiotic regimen safe after 2 weeks of intravenous treatment for primary bacterial vertebral osteomyelitis?". BMC Infectious Diseases. 14: 226. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-226. ISSN 1471-2334. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ↑ Torre, Jorge J. Jaramillo-de la; Bohinski, Robert J.; Kuntz, Charles (1 July 2006). "Vertebral Osteomyelitis". Neurosurgery Clinics. 17 (3): 339–351. doi:10.1016/j.nec.2006.05.003. ISSN 1042-3680. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ↑ "Spinal Fusion - OrthoInfo - AAOS". www.orthoinfo.org. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ↑ "Bone Graft". National Institute of Health. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ↑ Bono, Christopher (2004). Spine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 252. ISBN 9780781746137. Archived from the original on 2021-11-09. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- ↑ Breuninger, Marianne; Yagdiran, Ayla; Willinger, Anja; Biehl, Lena Maria; Otto-Lambertz, Christina; Kuhr, Kathrin; Seifert, Harald; Fätkenheuer, Gerd; Lehmann, Clara; Sobottke, Rolf; Siewe, Jan; Jung, Norma (15 October 2020). "Vertebral Osteomyelitis After Spine Surgery: A Disease With Distinct Characteristics". Spine. 45 (20): 1426–1434. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003542. ISSN 0362-2436. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.