User:QuackGuru/Sand

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37753443/ Effect of unguided e-cigarette provision on uptake, use, and smoking cessation among adults who smoke in the USA: a naturalistic, randomised, controlled clinical trial - Not a review

A 2021 review states that, "Formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein, carcinogenic nitrosamines N'-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) and nicotine-derived nitrosamine ketones (NNK) were found in vapors of a variety of e-cigarette products and are all carcinogenic to humans."[1]

Add more content. [2]

Need PDF file for article. Theodore L. Caputi https://www.jsad.com/doi/10.15288/jsad.2022.83.5 The Use of Academic Research in Medical Cannabis Marketing: A Qualitative and Quantitative Review of Company Websites

Cochrane Database of Systematic Review. [3] (PMC available on 2025-01-08)

Going cold turkey, or abruptly stopping vaping, can be a practical approach to quitting for some individuals.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electronic_cigarette

Electronic Cigarettes: Are They Smoking Cessation Aids or Health Hazards?

On November 16, 2022, the US FDA issued warning letters to the five firms for the unauthorized marketing of 15 different e-cigarette products.[7] Each e-cigarette product is packaged to look like toys, food, or cartoon characters and is likely to promote use by youth.[7] None of the companies submitted a premarket application for any of the unauthorized products.[7]

By April 2022, Vuse was at 35.1% and Juul was at 33.1% of the market in the US.[10]

Vuse's lead increased to 39.7%, while Juul's market share in the US slumped to 28.1% by September 2022.[11]

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6808a1.htm?s_cid=mm6808a1_w Upload image.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30817748/ DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6808a1 [14] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?linkname=pubmed_pubmed_citedin&from_uid=30817748&page=3

https://reftag.appspot.com/doiweb.py

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:Contributions/Apoc2400

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User_talk:Apoc2400#Wikipedia_citation_tool

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Help_talk:Citation_tools#Wikipedia_citation_tool_for_Google_Books

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organization, and the American Heart Association have significant reservations in opposition to vaping and came to the conclusion that there are significant health risks related to their use.[15]

May try yo trim "Youth" and "Motivation" sections.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electronic_cigarette

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27505084/

User:QuackGuru/Sand 1 Nicotine COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 2 Nicotine dependence. COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 3 Nicotine salt COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 4 Vape shop COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 5 Cloud-chasing COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 6 Electronic cigarette and e-cigarette liquid marketing COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 7 Composition of electronic cigarette aerosol COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 8 Usage of electronic cigarettes COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 9 Heated tobacco product COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 10 blu eCigs COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 11 Juul COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 12 Construction of electronic cigarettes COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 13 Research

User:QuackGuru/Sand 14 Nicotine pouch COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 15 Pod mod COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 16 List of electronic cigarette and e-cigarette liquid brands COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 17 List of heated tobacco products COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 18 Composition of heated tobacco product emissions COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 19 Positions of medical organizations on electronic cigarettes COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 20 Effects of nicotine and electronic cigarettes on human brain development COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 21 Regulation of electronic cigarettes COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 22 2019–2020 vaping lung illness outbreak COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 23 Simah Herman, et al. vs Juul Labs, Inc., et al. COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 24 Vaping-associated pulmonary injury COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 25 Health effects of electronic cigarettes COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 26 Knowledge Engine (search engine) COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 27 Larry Sanger

User:QuackGuru/Sand 28 Miscellaneous

User:QuackGuru/Sand 29 Paleolithic diet

User:QuackGuru/Sand 30 Everipedia

User:QuackGuru/Sand 31 Miscellaneous

User:QuackGuru/Sand 32 Toxicant COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 33 Elf Bar COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 34 Environmental impact of tobacco/Environmental impact of electronic cigarettes COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand 35 Vaping and cancer - NOT COMPLETED.

User:QuackGuru/Sand A Vaping - COMPLETED.

An electronic cigarette, also known as e-cigarette among other names,[note 1][17] is a battery-powered vaporizer that simulates smoking and provides some of the behavioral aspects of smoking, including the hand-to-mouth action of smoking, but without burning tobacco.[18] Using an e-cigarette is known as "vaping" and the user is referred to as a "vaper."[19] Instead of cigarette smoke, the user inhales an aerosol, commonly called vapor.[20] E-cigarettes typically have a heating element that atomizes a liquid solution called e-liquid.[21] E-cigarettes are activated by taking a puff.[22] Others turn on manually by pressing a button.[19] Some e-cigarettes look like traditional cigarettes,[23] and most versions are reusable.[note 2][24] There are various types of devices and a later type is a pod mod device.[25] E-liquids usually contain propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, flavorings, and additives[26] such as monosodium glutamate,[27] and can contain other substances such as the cannabinoids delta-9-THC, delta-8-THC, or cannabidiol,[28] and can contain differing amounts of contaminants[26] such as formaldehyde.[29] There is also a variety of unknown chemicals in the e-cigarette aerosol.[30]

The benefits and the health effects of e-cigarettes are uncertain.[31] They may help people quit smoking.[note 3][32] Children[33] and youth who vape are more likely to go on to smoke cigarettes.[34][35] Their usefulness as a tobacco harm reduction tool is unclear.[36] Regulated US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) nicotine replacement products may be safer than e-cigarettes,[37] but e-cigarettes are generally seen as safer than combusted tobacco products.[note 4][44][45][46] The long-term effects of e-cigarette use are unknown,[note 5][48][47][49] but it is more dangerous in the short-term than smoking.[42][50] Short-term use may lead to death.[42] Less serious adverse effects include abdominal pain, headache, blurry vision,[51] throat irritation, vomiting, nausea, and coughing.[52] Nicotine is highly addictive[40] and it poses an array of health risks[53] such as the stimulation of cancer development and growth.[note 6][46] In 2019 and 2020, an outbreak of severe vaping lung illness occurred in the US[56] and Canada.[note 7][58]

E-cigarettes create vapor made of fine and ultrafine particles of particulate matter,[52] which have been found to contain propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, flavors, small amounts of toxicants,[52] carcinogens,[note 8][1] and heavy metals, as well as metal nanoparticles, and other substances.[note 9][52] Its exact composition varies significantly across and within brands, and depends on the e-liquid contents, the device design, and user behavior, among other factors.[note 10][20] E-cigarette vapor potentially contains harmful chemicals not found in tobacco smoke.[62] E-cigarette vapor contains fewer toxic chemicals,[52] and lower concentrations of potentially toxic chemicals than in cigarette smoke.[63] During the stages when the brain is developing, there is a risk of brain damage to the unborn child, children, and adolescence from nicotine exposure.[26] Concern exists that the exhaled e-cigarette vapor may be inhaled by non-users, particularly indoors.[64] Children may be exposed to the developmental toxicant nicotine from indoor surfaces long after the e-cigarette vapor was exhaled.[26] Abstaining from vaping is beneficial for the environment.[65]

Since their entrance to the market in 2003,[54] global use has risen exponentially up to at least 2014.[66] The global number of adult e-cigarette users rose from around 7 million in 2011 to 41 million 2018,[67] and in 2021 it was estimated that there were 82 million e-cigarette users worldwide.[68] Most peoples' reason for vaping involve trying to quit smoking, though a large proportion use them recreationally.[22] Flavors appeal to non-smokers,[69] pregnant women,[70] young adults,[71] minors,[72] and children.[71] The e-cigarette was first invented by Herbert A. Gilbert in 1963, but the subsequent commercially viable design was patented by Hon Lik of China.[73] The revised EU Tobacco Products Directive came into effect in May 2016, providing stricter regulations for e-cigarettes.[74] As of August 2016, the US FDA extended its regulatory power to include e-cigarettes.[75] Large tobacco companies are actively marketing e-cigarettes to men smokers, men non-smokers, women, and children.[76] As of 2017[update], there were 433 brands of e-cigarettes.[77] Global sales were around $19.3 billion in 2019.[67]

Usage

Prevalence

Since the introduction of e-cigarettes to the market in 2003,[54] their global usage has risen exponentially up to at least 2014.[66] The global number of adult e-cigarette users rose from approximately 7 million in 2011 to 41 million in 2018.[67] It is estimated there were 82 million e-cigarette users worldwide in 2021[68] compared with approximately 1.1 billion tobacco smokers in 2019.[78] The prevalence of adult e-cigarette use in the US increased from 2.8% in 2017 to 3.2% in 2018.[79] In 2020, 19.6% of US high school students (3.02 million) and 4.7% of US middle school students (550,000) reported current e-cigarette use.[80] In the UK, current e-cigarette use increased from 1.7% of adults in 2012 to 7.1% in 2019 and then decreased to 6.3% in 2020.[81] As of 2020, 58.9% of UK adult e-cigarette users are former smokers, 38.3% currently use both combustible tobacco and e-cigarettes, and 2.9% of never smokers are e-cigarette users.[81]

E-cigarette use in the US and Europe is higher than in other countries,[22] except for China which has the greatest number of e-cigarette users.[82] Targeted advertising strategies by the tobacco industry has led to an increase in e-cigarette use among youths, people of color, and people of the LGBTQ+ community.[83] A 2016 review states that the growing prevalence of e-cigarette use may be due to heavy promotion in youth-driven media channels, their low cost, and the misbelief that e-cigarettes are safer than traditional cigarettes.[84] As of 2022, the use of e-cigarettes among young people, including adolescents and emerging adults, is a rising concern worldwide.[note 11][12]

The introduction of e-cigarettes has given cannabis smokers a different way of inhaling cannabinoids.[85] Recreational cannabis users can individually "vape" deodorized or flavored cannabis extracts with minimal annoyance to the people around them and less chance of detection, known as "stealth vaping".[85] There is a link between teen e-cigarette use and using other chemicals, including alcohol, cannabis, and amphetamines, in addition to other hazardous behaviors like fighting and trying to commit suicide, which are highest among dual e-cigarette and traditional cigarette users.[86]

Subsequent smoking initiation

E-cigarette use is consistently associated with higher odds of starting smoking and continuing smoking.[87] There is compelling evidence that starting to vape leads to starting cigarette smoking, in addition to previous 30-day vaping leads to resulting previous 30-day cigarette smoking, among young adults and adolescents.[88] There is strong evidence for young adults and youth that e-cigarette use increases the chance of one-time traditional cigarette use.[89] The evidence indicates that the pod mods such as Juul that can provide greater levels of nicotine could increase the chance for users to transition from vaping to smoking cigarettes.[17] Higher levels of nicotine in e-cigarettes have been associated with an increase in the frequency and intensity of combustible cigarette smoking.[90]

There is concern regarding that the accessibility of e-liquid flavors could lead to using additional tobacco products among non-smokers.[69] A 2015 review argued for the implementation of the precautionary principle because vaping by non-smokers may lead to smoking.[91] There is a concern with the possibility that non-smokers as well as children may start nicotine use with e-cigarettes at a rate higher than anticipated than if they were never created.[92] In certain cases, e-cigarettes might increase the likelihood of being exposed to nicotine itself, especially for never-nicotine users who start using nicotine products only as a result of these devices.[24]

Because those with mental illness are highly predisposed to nicotine addiction, those who try e-cigarettes may be more likely to become dependent, raising concerns about facilitating a transition to combustible tobacco use.[93] Even if an e-cigarette contains no nicotine, the user mimics the actions of smoking.[94] This may renormalize tobacco use in the general public.[94] Normalization of e-cigarette use may lead former cigarette smokers to begin using them, thereby reinstating their nicotine dependence and fostering a return to tobacco use.[95] There is a possible risk of re-normalizing of tobacco use in areas where smoking is banned.[94]

Pregnancy

E-cigarette use is rising among women, including women of childbearing age as of 2014[update].[96] Many woman who vape do not stop during pregnancy because of their perceived safety in comparison with tobacco.[97] In one of the few studies identified, a 2015 survey of 316 pregnant women in a Maryland clinic found that the majority had heard of e-cigarettes, 13% had ever used them, and 0.6% were current daily users.[98] These findings are of concern because the dose of nicotine delivered by e-cigarettes can be as high or higher than that delivered by traditional cigarettes.[98] Vaping prevalence in pregnant women has been estimated to stand between 0.6 and 15%.[13] The rate of e-cigarette use among pregnant adolescents is unknown.[98] Vaping during pregnancy is associated with cigarette smoking.[99]

Youth

The prevalence of vaping among minors has increased worldwide,[102] though there is substantial variability in vaping among minors worldwide.[103] For example, one-time e-cigarette use among minors went up in Poland, Korea, New Zealand, and the US; went down in Italy and Canada; and was about the same in the UK, in 2008 to 2015.[103] Vaping among adolescents has grown every year leading up to 2017.[104] In contrast with a consistent decline in smoking prevalence among youth, over the past few years leading up to 2019 e-cigarettes have rapidly gained popularity to the point of becoming the most common tobacco product in this age group.[13] Their social acceptance, together with their widespread availability, contributed to drastically increase primary use by adolescents and second-hand exposure in children.[13] The prevalence of vaping among children has grown.[105] As of 2014, there appears to be an increase of one-time e-cigarette use among young people worldwide.[106] The prevalence of vaping in youth is common.[17]

Most e-cigarette users among youth have never smoked.[107] Some youths who have tried an e-cigarette have never used a traditional cigarette; indicating e-cigarettes may be a starting point for nicotine use.[52] Adolescents who would have not been using nicotine products to begin with are vaping.[108] Twice as many youth vaped in 2014 than also used traditional cigarettes.[109] E-cigarettes are expanding the nicotine market by attracting low-risk youth who would be unlikely to initiate nicotine use with traditional cigarettes.[55] Data from a longitudinal cohort study of children with alcoholic parents found that adolescents (both middle and late adolescence) who used cigarettes, marijuana, or alcohol were significantly more likely to have ever used e-cigarettes.[98] Adolescents were more likely to initiate vaping through flavored e-cigarettes.[72] Among youth who have ever tried an e-cigarette, a majority used a flavored product the first time they tried an e-cigarette.[98] In adolescents, the green apple flavorant was found to increase vaping behavior compared to both menthol-flavored and unflavored e-cigarettes.[110] Pod mod devices are very popular among youth.[111]

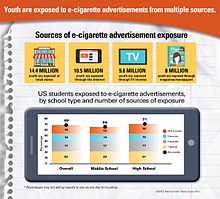

Most youth are not vaping to help them quit tobacco.[113] Adolescent vaping is unlikely to be associated with trying to reduce or quit tobacco.[114] A 2015 study found minors had little resistance to buying e-cigarettes online.[62] Teenagers may not admit to using e-cigarettes, but use, for instance, a hookah pen.[115] As a result, self-reporting may be lower in surveys.[115] Experts suggest that candy-like flavors could lead youths to experiment with vaping.[92] E-cigarette advertisements seen by youth could increase the likelihood among youths to experiment with vaping.[116] A 2016 review found "The reasons for the increasing use of e-cigarettes by minors (persons between 12 and 17 years of age) may include robust marketing and advertising campaigns that showcase celebrities, popular activities, evocative images, and appealing flavors, such as cotton candy."[117] A 2014 survey stated that vapers may have less social and behavioral stigma than cigarette smokers, causing concern that vaping products are enticing youth who may not under other circumstances have used these products.[118] The prevalence of vaping is higher in adolescent with asthma than in adolescent who do not have asthma.[119] Childhood trauma may increase the odds of vaping in youth.[120]

Subsequent youth smoking initiation

Many youth who use e-cigarettes also smoke traditional cigarettes.[52] Vaping seems to be a gateway to using traditional cigarettes in adolescents.[121] Youth who use e-cigarettes are more likely to go on to use traditional cigarettes.[34][35] The evidence suggests that young people who vape are also at greater risk for subsequent long-term tobacco use.[122] Youth who use non-reusable and various reusable e-cigarettes is connected with a higher odds of using smokable tobacco products.[123] There is a consistent link between nicotine-free vaping and nicotine vaping and later tobacco use in people under the age of 20 across a multitude of studies worldwide.[124]

Adolescents who vape but do not smoke are more than twice as likely to intend to try smoking than their peers who do not vape.[107] Vaping is correlated with a higher occurrence of cigarette smoking among adolescents, even in those who otherwise may not have been interested in smoking.[125] Adolescence experimenting with e-cigarettes appears to encourage continued use of traditional cigarettes.[44] Flavor restrictions may successfully reduce e-cigarette initiation and remove a potential gateway to combustible tobacco use among youth.[126] Government intervention is recommended to keep children safe from the re-normalizing of tobacco, according to a 2017 review.[104] There is a greater likelihood of past or present and later cannabis use among youth and young adults who have vaped.[127] Adolescent and young adult one-time e-cigarette use is linked to an increased risk of later cannabis and other illegal drug use.[128]

Motivation

Reasons for initialing or continuing use

There are varied reasons for e-cigarette use.[22] Most users' motivation is related to trying to quit smoking, but a large proportion of use is recreational.[22] Adults cite predominantly three reasons for trying and using e-cigarettes: as an aid to smoking cessation, a belief that they are a safer alternative to traditional cigarettes, and as a way to conveniently get around smoke-free laws.[55] The majority of e-cigarette users state that flavor is a major reason in starting their use and ongoing use.[132] Adolescent experimenting with e-cigarettes may be related to sensation seeking behavior, and is not likely to be associated with tobacco reduction or quitting smoking.[114]

Many users vape because they believe it is healthier than smoking for themselves or bystanders.[23] Usually, only a small proportion of users are concerned about the potential adverse health effects.[23] Some people say they want to quit smoking by vaping, but others vape to circumvent smoke-free laws and policies, or to cut back on cigarette smoking.[52] Seniors seem to vape to quit smoking or to get around smoke‐free policies.[97] Concerns over avoiding stains on teeth or odor from smoke on clothes in some cases prompted interest in or use of e-cigarettes.[23] Some e-cigarettes appeal considerably to people curious in technology who want to customize their devices.[133] There appears to be a hereditary component to tobacco use, which probably plays a part in transitioning of e-cigarette use from experimentation to routine use.[21]

Marketing messages echo well-established cigarette themes, including freedom, good taste, romance, sexuality, and sociability as well as messages stating that e-cigarettes are healthy, are useful for smoking cessation, and can be used in smoke free environments.[55] These messages are mirrored in the reasons that adults and youth cite for using e-cigarettes.[55] Exposure to e-cigarette advertising influences people to try them.[115] E-liquid flavors are enticing to a range of smokers and non-smokers.[69] Among current e-cigarette users, e-liquid flavor availability is very appealing.[93] Candy-, fruit- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes appeal to adolescents more as compared to tobacco-flavored traditional cigarettes [134]

The belief that e-cigarettes are safer than traditional cigarettes could widen their use among pregnant women.[114] If tobacco businesses persuade women that e-cigarettes are a small risk, non-smoking women of reproductive age might start using them and women smoking during pregnancy might switch to their use or use these devices to reduce smoking, instead of quitting smoking altogether.[26] E-cigarettes users' views about saving money from using e-cigarettes compared to traditional cigarettes are inconsistent.[23] The majority of committed e-cigarette users interviewed at an e-cigarette convention found them cheaper than traditional cigarettes.[23]

Reasons for discounting use

Some users stopped vaping due to issues with the devices.[23] Dissatisfaction and concerns over safety can discourage ongoing e-cigarette use.[135] Commonly reported issues with using e-cigarettes were that the devices were hard to refill, the cartridges might leak and that altering the dose was hard.[136] Smokers mainly quit vaping because it did not feel similar to traditional cigarettes, did not aid with cravings, and because they wanted to use them only to know what they were like.[137]

Gateway theory

In the context of drugs, the gateway hypothesis predicts that the use of less deleterious drugs can lead to a future risk of using more dangerous hard drugs or crime.[138] There is wide concern that vaping may be a "gateway" to smoking.[139] Vaping may also act as a gateway to illicit drug use (recreational use of illegal drugs), is an area of concern.[140] Studies indicate vaping serves as a gateway to traditional cigarettes and cannabis use.[17] Nicotine is a gateway to opioid addiction, as nicotine lowers the threshold for addiction to other agents.[141] A 2015 review concluded that "Nicotine acts as a gateway drug on the brain, and this effect is likely to occur whether the exposure is from smoking tobacco, passive tobacco smoke or e-cigarettes."[142] Vaping without nicotine seems to act as a gateway device.[42]

Under the common liability model, some have suggested that any favorable relation between vaping and starting smoking is a result of common risk factors.[143] This includes impulsive and sensation seeking personality types or exposure to people who are sympathetic with smoking and relatives.[143] A 2014 review using animal models found that nicotine exposure may increase the likelihood to using other drugs, independent of factors associated with a common liability.[note 12][145] The gateway theory, in relation to using nicotine, has also been used as a way to propose that using tobacco-free nicotine is probably going to lead to using nicotine via tobacco smoking, and therefore that vaping by non-smokers, and especially by children, may result in smoking independent of other factors associated with starting smoking.[145] Some see the gateway model as a way to illustrate the potential risk-heightening effect of vaping and going on to use combusted tobacco products.[146]

The "catalyst model" suggests that vaping may proliferate smoking in minors by sensitizing minors to nicotine with the use of a type of nicotine that is more pleasing and without the negative attributes of regular cigarettes.[147] A 2016 review, based on the catalyst model, suggests "that the perceived health risks, specific product characteristics (such as taste, price and inconspicuous use), and higher levels of acceptance among peers and others potentially make e-cigarettes initially more attractive to adolescents than tobacco cigarettes. Later, increasing familiarity with nicotine could lead to the reevaluation of both electronic and tobacco cigarettes and subsequently to a potential transition to tobacco smoking."[102]

While the evidence is constrained by publication and attrition bias and adequately controling for possible confounding factors, there is a longitudinal relationship between teen vaping and trying smoking.[148] It is unclear to the degree that the relationship is a gateway effect or is the result of common liability.[148] Although the association between e-cigarette use among non-smokers and subsequent smoking appears strong, the available evidence is limited by the reliance on self-report measures of smoking history without biochemical verification.[149] None of the studies cited in a 2021 review included negative controls which would provide stronger evidence for whether the association may be causal.[149] A considerable amount of the evidence also failed to consider the nicotine content of e-liquids used by non-smokers, which means it is difficult to make conclusions about whether nicotine is the mechanism driving this association.[149]

Construction

An e-cigarette is a battery-powered vaporizer that simulates smoking, but without tobacco combustion.[18] E-cigarette components include a mouthpiece (drip tip[150]), a cartridge (liquid storage area), a heating element/atomizer, a microprocessor, a battery, and some of them have an LED light on the end.[151] An atomizer consists of a small heating element, or coil, that vaporizes e-liquid and a wicking material that draws liquid onto the coil.[152] When the user inhales a flow sensor activates the heating element that atomizes the liquid solution;[22] most devices are manually activated by a push-button.[153] The e-liquid reaches a temperature of roughly 100–250 °C (212–482 °F) within a chamber to create an aerosolized vapor.[154] The user inhales an aerosol, which is commonly but inaccurately called vapor, rather than cigarette smoke.[note 13][20] Vaping is different from smoking, but there are some similarities, including the hand-to-mouth action of smoking and a vapor that looks like cigarette smoke.[18] The aerosol provides a flavor and feel similar to smoking.[18] A traditional cigarette is smooth and light but an e-cigarette is rigid, cold and slightly heavier.[18] There is a learning curve to use e-cigarettes properly.[23] E-cigarettes are cigarette-shaped,[52] but there are many other variations.[19] E-cigarettes that resemble pens or USB memory sticks are also sold that may be used unobtrusively.[156]

There are various types of e-cigarettes: cigalikes that look like cigarettes; tank models that are bigger than cigalikes and have refillable liquid tanks; and mods, assembled from basic parts or by altering existing products.[114] Cigalikes are either disposable or come with rechargeable batteries and replaceable nicotine cartridges.[157] A cigalike e-cigarette contains a cartomizer, which is connected to a battery.[54] A "cartomizer" (a portmanteau of cartridge and atomizer[158]) or "carto" consists of an atomizer surrounded by a liquid-soaked poly-foam that acts as an e-liquid holder.[152] Clearomizers or "clearos", not unlike cartotanks, use a clear tank in which an atomizer is inserted.[159] A rebuildable atomizer or an RBA is an atomizer that allows users to assemble or "build" the wick and coil themselves instead of replacing them with off-the-shelf atomizer "heads".[160] The power source is the biggest component of an e-cigarette,[66] which is frequently a rechargeable lithium-ion battery.[19]

As the e-cigarette industry continues to evolve, new products are quickly developed and brought to market.[161] First-generation e-cigarettes tend to look like traditional cigarettes and so are called "cigalikes".[160] Most cigalikes look similar to cigarettes but there is some differences in size.[54] Second-generation devices are larger than cigalikes and look less similar to traditional cigarettes.[54] Third-generation devices are larger than second-generation devices[54] and the voltage is adjustable.[162] The fourth-generation includes sub ohm tanks and temperature control devices.[163] The voltage for first-generation e-cigarettes is about 3.7[76] and second-generation e-cigarettes can be adjusted from 3 V to 6 V,[164] while more recent devices can go up to 8 V.[76] The latest generation of e-cigarettes are pod mods,[25] which provide higher levels of nicotine than regular e-cigarettes[165] through the production of aerosolized protonated nicotine.[166]

E-liquid is the mixture used in vapor products such as e-cigarettes[167] and usually contain propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, flavorings, and additives[26] such as monosodium glutamate,[27] and can contain other substances such as the cannabinoids delta-9-THC, delta-8-THC, or cannabidiol,[28] and can contain differing amounts of contaminants[26] such as formaldehyde.[29] E-liquid formulations greatly vary due to fast growth and changes in manufacturing designs of e-cigarettes.[54] The composition of the e-liquid for additives such as nicotine and flavors vary across and within brands.[168] The liquid typically consists of a combined total of 95% propylene glycol and glycerin, and the remaining 5% being flavorings, nicotine, and other additives.[169] There are e-liquids sold without propylene glycol,[170] nicotine,[171] or flavors.[172] The flavorings may be natural, artificial,[168] or organic.[173] Over 80 chemicals such as formaldehyde and metallic nanoparticles have been found in the e-liquids.[note 14][176] There are many e-liquids manufacturers in the US and worldwide,[177] and more than 15,500 flavors existed in 2018.[178] Under the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rules, e-liquid manufacturers are required to comply with a number of manufacturing standards.[179] The revision to the EU Tobacco Products Directive has some standards for e-liquids.[180] Voluntary standards are published by the American E-Liquid Manufacturing Standards Association.[181] At least nine countries have restricted the sale of flavored e-cigarettes in some way.[126]

Health effects

Positions of medical organizations

The scientific community in the US and Europe are primarily concerned with their potential consequence on public health.[182] There is concern among public health experts that e-cigarettes could renormalize smoking, weaken measures to control tobacco,[183] and serve as a gateway for smoking among youth.[184] The public health community is divided over whether to support e-cigarettes, because their safety and efficacy for quitting smoking is unclear.[185] Many in the public health community acknowledge the potential for their quitting smoking and decreasing harm benefits, but there remains a concern over their long-term safety and potential for a new era of users to get addicted to nicotine and then tobacco.[184] There is concern among tobacco control academics and advocates that prevalent universal vaping "will bring its own distinct but as yet unknown health risks in the same way tobacco smoking did, as a result of chronic exposure."[186]

Medical organizations differ in their views about the health implications of vaping.[187] Numerous public health groups and professional organizations around the world have characterized their use as a major public health problem.[32] The majority of governing bodies do not support e-cigarettes as a quitting smoking aid.[32] Some healthcare groups and policy makers have hesitated to recommend e-cigarettes for quitting smoking, because of their limited evidence of effectiveness and safety.[188] Some have advocated bans on e-cigarette sales and others have suggested that e-cigarettes may be regulated as tobacco products but with less nicotine content or be regulated as a medicinal product.[189]

A 2019 World Health Organization report found that the existing evidence does not backup the tobacco industry's view that vaping is less dangerous than combustible tobacco products and that the scientific evidence is insufficient to support vaping as a smoking cessation tool.[190] Healthcare organizations in the UK including Public Health England have encouraged smokers to try e-cigarettes to help them quit smoking and also encouraged e-cigarette users to quit smoking tobacco entirely.[191] The American Heart Association and other cardiovascular medical societies repeatedly published warnings regarding e-cigarette vaping.[192] In 2016, the US FDA stated that "Although ENDS [electronic nicotine delivery systems] may potentially provide cessation benefits to individual smokers, no ENDS have been approved as effective cessation aids."[193] In 2019, the European Respiratory Society stated that the long-term impact of using e-cigarettes remains unknown, and as a result, it cannot be definitively stated that these devices are safer than traditional tobacco products in the long run.[47]

Smoking cessation

The available research on the efficacy of e-cigarette use for smoking cessation is limited.[139] Their use for quitting smoking is controversial.[195][196][197] The role of e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation tool is hotly contested.[198] Data regarding their use includes at least 47 randomized controlled trials[3] and an increasing number of user surveys, case reports, and cohort studies.[186] There is a lack of quality evidence in cohort studies and randomized controlled trials showing e-cigarette use leads to quitting smoking.[199] Studies determining whether e-cigarettes can help as a smoking cessation aid have come to conflicting conclusions.[156] There exists contradictory data that can either support or dismiss vaping as an aid to quitting smoking.[200] Due to limitations in the evidence stemming from methodological and study design constraints, no firm conclusions can be drawn in regard to their efficacy and safety.[201] No long-term trials have been conducted for their use as a smoking cessation aid.[202] It is still not evident as to whether vaping can adequately assist with quitting smoking at the population level.[203]

Nicotine vaping may help individuals quit smoking for a minimum of six months.[3] Vaping does not greatly increase the odds of quitting smoking[204] and they may be an impediment to entirely quitting smoking.[205] Using e-cigarettes as a way to quit smoking may result in a lifetime of nicotine dependence.[174] A 2019 randomized trial resulted in more smokers becoming dual users than succeeded in complete abstinence after a year.[206] The same trial found that, "while 18% of the e-cigarette users achieved complete abstinence, 25% (110/438) became dual users of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes."[206] Some studies suggest that there are increased smoking relapse rates when e-cigarettes are used as a cessation tool.[198] Many smokers succeed in switching to e-cigarettes for a short period, but most relapse to conventional cigarette smoking.[note 15][68] A 2015 PHE report recommends for smokers who cannot or do not want to quit to use e-cigarettes as one of the main steps to lower smoking-related disease,[207] while a 2015 US PSTF statement found there is not enough evidence to recommend e-cigarettes for quitting smoking in adults, pregnant women, and adolescents.[208] In 2021 the US PSTF concluded the evidence is still lacking to recommend e-cigarettes for quitting smoking, finding that the balance of risks and benefits remains uncertain.[209] As of January 2018[update], systematic reviews collectively agreed that there is insufficient evidence to unequivocally determine whether vaping helped people abstain from smoking.[210] A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis found that on the whole as consumer products e-cigarettes have not been shown to increase quitting smoking.[211]

Studies pertaining to their potential impact on smoking reduction are very limited.[212] E-cigarette use may decrease the number of cigarettes smoked,[213] but smoking just one to four cigarettes daily greatly increases the risk of cardiovascular disease compared to not smoking.[52] The extent to which decreasing cigarette smoking with vaping leads to quitting is unknown.[214] The effectiveness of vaping in decreasing or abolishing smoking is questionable.[215] Randomized controlled trials have not shown that vaping is effective for quitting smoking.[200] A 2016 meta-analysis based on 20 different studies found that smokers who used e-cigarettes were 28% less likely to quit than those who had not tried e-cigarettes.[216] This finding persisted whether the smokers were initially interested in quitting or not.[216] Tentative evidence indicates that health warnings on vaping products may influence users to give up vaping.[217] Many people who use e-cigarettes still smoke, raising concern that they may be delaying or deterring quitting.[52]

It is unclear whether e-cigarettes are only helpful for particular types of smokers.[218] Vaping with nicotine may reduce tobacco use among daily smokers.[219] Whether vaping is potentially effective for quitting smoking may depend on whether it was used as part of an effort to quit.[212]

Vaping is not clearly more or less effective than regulated nicotine replacement products or 'usual care' for quitting smoking.[200] The available research suggests e-cigarettes are likely equal or slightly better than nicotine patches for quitting smoking.[54] People who vaped were not more likely to give up smoking than people who did not vape.[220] Compared to many alternative quitting smoking medicines in early development in clinical trials including e-cigarettes, cytisine appears to be most encouraging in efficacy and safety with an inexpensive price.[221] A 2018 study involving 54 people of very low strength of the evidence found more individuals stopped smoking who were given varenicline than those who used e‐cigarettes.[222]

E-cigarettes have not been proven to be more effective than smoking cessation medicine[223][224] and regulated US FDA medicine.[225][114] Not a single e-cigarette has been approved as medicine for quitting smoking by the US FDA or the European Medicines Agency.[174] E-cigarettes are recommended as cessation tools in some countries.[68] A 2014 review found that they are equally effective, but not more effective, than nicotine patches for short-term quitting smoking.[113] They also found that a randomized trial stated 29% of e-cigarette users were still vaping at 6 months, while only 8% of patch users still wore patches at 6 months.[113] Some individuals who quit smoking with a vaping device are continuing to vape after a year.[226] Vaping appears to be as effective as nicotine replacement products, though its potential adverse effects such as normalizing smoking have not been adequately studied.[227] There is strong evidence for people who already smoke that nicotine vaping has a higher quit rate than nicotine replacement products in supervised clinical trials lasting for a minimum of six months.[3] This might mean eight to 10 individuals successfully quit per 100, compared with six of 100 of individuals using nicotine replacement products, or seven of 100 vaping with no nicotine.[3] While some surveys reported improved quitting smoking, particularly with intensive e-cigarette users, several studies showed a decline in quitting smoking in dual users.[19] A 2015 overview of systematic reviews indicates that e-cigarettes has no benefit for smokers trying to quit, and that the high rate of dual use indicates that e-cigarettes are used for supporting their nicotine addiction.[228] Other kinds of nicotine replacement products are usually covered by health systems, but because e-cigarettes are not medically licensed they are not covered.[226]

It is difficult to reach a general conclusion from e-cigarette use for smoking cessation because there are hundreds of brands and models of e-cigarettes sold that vary in the composition of the liquid.[189] E-cigarettes have not been subjected to the same type of efficacy testing as nicotine replacement products.[229] The similarity of e-cigarettes' vapor, looking like cigarette smoke, may prolong traditional cigarette use for people who could have quit instead, but the growing support of e-cigarettes could put extra pressure on smokers to stop cigarette smoking because smoking may be seen as socially unacceptable compared to a smokeless e-cigarette.[185] The evidence indicates smokers are more frequently able to completely quit smoking using tank devices compared to cigalikes, which may be due to their more efficient nicotine delivery.[230] There is low quality evidence that vaping assists smokers to quit smoking in the long-term compared with nicotine-free vaping.[230] Nicotine-containing e-cigarettes were associated with greater effectiveness for quitting smoking than e-cigarettes without nicotine.[231] A 2013 study in smokers who were not trying to quit, found that vaping, with or without nicotine decreased the number of cigarettes consumed.[232] E-cigarettes without nicotine may reduce tobacco cravings because of the smoking-related physical stimuli.[233] A 2015 meta-analysis on clinical trials found that e-cigarettes containing nicotine are more effective than nicotine-free ones for quitting smoking.[231] They compared their finding that nicotine-containing e-cigarettes helped 20% of people quit with the results from other studies that found nicotine replacement products helps 10% of people quit.[231] A 2016 review found low quality evidence of a trend towards benefit of e-cigarettes with nicotine for smoking cessation.[201]

Intervention studies examining vaping for quitting smoking for at least 6 months have rendered a scarcity of information on the prevalence of e-liquid flavors used and any possible effect they have on quitting smoking and vaping over the long-term.[234] The part that e-liquid flavors play in quitting smoking among youth is unclear.[235] In terms of whether flavored e-cigarettes assisted quitting smoking, the evidence is inconclusive.[72] Information on the role of the various flavors of e-cigarettes used and successfully stopping smoking is not clear.[236] This is because of the inconsistency in the conclusions and methodological constraints of the studies evaluated.[236]

As of 2020, the efficacy and safety of vaping for quitting smoking during pregnancy is unknown.[237] No research is available to provide details on the efficacy of vaping for quitting smoking during pregnancy.[238] The behavioral similarities between smoking and vaping were a barrier to smoking cessation for some young adults.[239] There is robust evidence that vaping is not effective for quitting smoking among adolescents.[125] In view of the shortage of evidence, vaping is not recommend for cancer patients.[240] The effectiveness of vaping for quitting smoking among vulnerable groups is uncertain.[241] There is a lack of research to recommend vaping as a way to quitting smoking for vulnerable groups, including individuals with schizophrenia.[242] Although vaping might help lower tobacco use in people with schizophrenia, psychotic disorders or mental illness, the evidence continues to be uncertain if it will help with quitting smoking.[243]

Vaping cessation

.

Because of the escalation of e-cigarette use and other vaping devices, in addition to the lack of certainty regarding their adverse effects, a 2021 review concluded that it is imperative to establish scientifically-supported guidelines to aid individuals in the discontinuation of vaping practices.[245] There is good evidence that e-cigarette users and dual users are trying to obtain information on how to stop vaping.[246] This is due to health risks such as a greater chance of injury from COVID-19.[246] Although a considerable number of youth and adults want to stop vaping, youth seems to express a greater desire in stopping vaping.[247] Youth were incited to give up vaping due health concerns while adults were incited to give up vaping due to price, lack of enjoyment, and psychological reasons.[247] Seeing messages associated with the harms of vaping were associated with a greater intent to stop vaping.[247]

There is a lack of evidence backing up effective ways to quit vaping.[246] Evidence-based clinical guidelines for quitting vaping among adults have not been created.[248] As of 2019, treatment approaches are in their beginning stages and no formal recommendation is available for how to encourage quitting vaping among youth.[249] In schooling interventions, media campaigns, and policy recommendations have been presented as ways to assist with reducing e-cigarette use.[250] Managing cravings from nicotine withdrawal is one of the major difficulties with ceasing e-cigarette use.[251] Exercising, creating an atmosphere to prevent temptations, implementing a distraction technique, and identifying ways to avert stress have been proposed to tackle cravings from vaping.[251] While there is a lack of information and strategies for assisting youth and young adults to give up e-cigarette use, there is general agreement that clinicians should not advocate e-cigarette use to youth and young adults as a way for stopping tobacco cigarette use.[251]

There are support services available, such as Smokefree Teen, to help teens quit vaping.[253] In January 2019, the Truth Initiative made available at no charge a vaping cessation system for minors and young adults named "This is Quitting."[251] It is a text-based system that allows users to get involved and arrange or not to arrange a halt to vaping date.[251] To begin, the text "QUIT" is sent to a specific number.[251] Within the first 12 weeks of starting the system, greater than 30,000 young people signed up.[251] The majority of users arranged a discontinue vaping date and at two weeks, close to 61% of respondents stated they had vaped less or gave up vaping.[251] This suggests that an easily accessible text message intervention to encourage vaping cessation is attractive to young people.[251] The US FDA has partnered with the National Cancer Institute's Smokefree.gov initiative to provide youth with resources for quitting e-cigarettes.[254] The Canadian Cancer Society offers various services to help people quit vaping.[255] Going cold turkey has been used as a way to stopping vaping, but it is unclear how effective this method is.[247] Many organizations including the American Lung Association, World Health Organization, Smokefree.gov, and Truth Initiative advocate to stop vaping and disapprove of replacing cigarettes with e-cigarettes.[246]

—Peter Laucks and Gary A. Salzman, Missouri medicine[256]

As of 2022, there have been limited community-based and public health intervention trials to assist with e-cigarette prevention.[257] "Catch my breath" was a prevention intervention in 12 middle schools across the US in 2020.[257] The intervention focused on increasing knowledge on the harms associated with e-cigarette use.[257] The study authors found statistically significant differences in e-cigarette use prevalence in schools that had implemented the program when compared with control schools.[257] They also found increased knowledge of e-cigarettes and the risks associated with their use.[257]

Public health interventions targeting existing teenage users are in their infancy, as of 2022.[257] There is a current text messaging intervention for e-cigarette cessation in teens in the US.[257] The intervention provides users with educational content on e-cigarettes, focuses on fostering self-efficacy, assists with resilience building, and provides users with support and encouragement.[257] The study in 2020 had a very high enrollment after about one month of recruitment, with over 27,000 teenagers and young adults enrolled.[257] This indicates that this form of intervention is feasible, given the willingness for e-cigarette users to enroll.[257] Previous studies have found that text messaging for smoking cessation is effective and acceptable for this population, indicating that it could be used for vaping.[257]

As of 2022, there are very few commercially available e-cigarette cessation apps that can help teenagers and young adults quit.[257] A 2020 systematic review of apps in the Google Play Store found that most apps encouraged e-cigarette use and that only two out of 79 were vaping cessation apps.[257]

Because it is taken orally with few adverse effects, varenicline may be a suitable and effective intervention for people who have not given up vaping with other interventions.[248] No guidelines exist in the form of clinical studies or case reports for using bupropion for quitting vaping.[248] There is limited information available on nicotine replacement products for stopping vaping.[248] A 2016 case study of a 24-year-old male stated that he had successfully quit vaping with the use of nicotine replacement products.[248] Combining behavioral therapy with one of the efficacious pharmacotherapy agents leads to greater success in discontinuing smoking than just pharmacotherapy by itself.[248] A 2023 review states, this combined strategy can also be utilized for those who want to quit vaping.[248]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34348566/ wait for review

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33407805/ wait for review

Harm reduction

The term harm reduction implies any reduction in relative harm from a prior level, even a small reduction such as reducing smoking by one or two cigarettes per day.[259] Harm minimization strives to reduce harms to zero (i.e., ideally to no use and thus no harmful exposure).[259] When a consumer does not want to stop all nicotine use, then harm minimization implies striving for the complete elimination of smoked tobacco exposure by substituting it with the use of less harmful noncombusted forms of nicotine instead of smoking.[259] Tobacco harm reduction may serve as a substitute for traditional cigarettes with lower risk products to reduce tobacco-related death and disease.[260]

Tobacco harm reduction has been a controversial area of tobacco control.[233] Health advocates have been slow to support a harm reduction method out of concern that tobacco companies cannot be trusted to sell products that will lower the risks associated with tobacco use.[233] E-cigarettes can reduce smokers' exposure to carcinogens and other toxic chemicals found in tobacco.[21] A large number of smokers want to reduce harm from smoking by using e-cigarettes.[261] The argument for harm reduction does not take into account the adverse effects of nicotine.[156] The European Respiratory Society has stated that "The tobacco harm reduction strategy is based on well-meaning but incorrect or undocumented claims or assumptions",[262] while Ghazi Zaatari, the chair of the World Health Organization study group on tobacco product regulation, has indicated that "The notion of harm reduction is a trap by the tobacco industry trying to perpetuate nicotine addiction."[263] There cannot be a defensible reason for harm reduction in children who are vaping with a base of nicotine.[264] Quitting smoking is the most effective strategy to tobacco harm reduction.[265]

Tobacco smoke contains 100 known carcinogens, and 900 potentially cancer causing chemicals, but e-cigarette vapor contains less of the potential carcinogens than found in tobacco smoke.[170] A study in 2015 using a third-generation device found levels of formaldehyde were greater than with cigarette smoke when adjusted to a maximum power setting.[172] E-cigarettes cannot be considered safe because there is no safe level for carcinogens.[233] Due to their similarity to traditional cigarettes, e-cigarettes could play a valuable role in tobacco harm reduction.[185] However, the public health community remains divided concerning the appropriateness of endorsing a device whose safety and efficacy for smoking cessation remain unclear.[185] Overall, the available evidence supports the cautionary implementation of harm reduction interventions aimed at promoting e-cigarettes as attractive and competitive alternatives to cigarette smoking, while taking measures to protect vulnerable groups and individuals.[185]

The core concern is that smokers who could have quit entirely will develop an alternative nicotine addiction.[233] Dual use may be an increased risk to a smoker who continues to use even a minimal amount of traditional cigarettes, rather than quitting.[52] Whether they ought to be recommended as a tobacco harm reduction aid is unclear because the longer term health consequences of inhaling e-cigarette-exclusive chemicals is not fully known.[36] Evidence to substantiate the potential of vaping to lower tobacco-related death and disease is unknown.[238] The health benefits of reducing cigarette use while vaping is unclear.[266] E-cigarettes could have an influential role in tobacco harm reduction.[185] Without clear evidence of a role in the reduction of tobacco dependence, e-cigarettes risk renormalizing and re-glamorizing smoking.[198] This is of paramount concern, potentially undoing years of effort by the public health and medical communities.[198]

A 2014 review recommended that regulations for e-cigarettes could be similar to those for dietary supplements or cosmetic products to not limit their potential for harm reduction.[260] A 2012 review found e-cigarettes could considerably reduce traditional cigarettes use and they likely could be used as a lower risk replacement for traditional cigarettes, but there is not enough data on their safety and efficacy to draw definite conclusions.[18] There is no research available on vaping for reducing harm in high-risk groups such as people with mental disorders.[267]

A 2014 PHE report concluded that hazards associated with products currently on the market are probably low, and apparently much lower than smoking.[261] However, harms could be reduced further through reasonable product standards.[261] The British Medical Association encourages health professionals to recommend conventional nicotine replacement therapies, but for patients unwilling to use or continue using such methods, health professionals may present e-cigarettes as a lower-risk option than tobacco smoking.[268] The American Association of Public Health Physicians (AAPHP) suggests those who are unwilling to quit tobacco smoking or unable to quit with medical advice and pharmaceutical methods should consider other nicotine containing products such as e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco for long-term use instead of smoking.[269] A 2014 World Health Organization report concluded that some smokers will switch completely to e-cigarettes from traditional tobacco but a "sizeable" number will use both.[92] This report found that such "dual use" of e-cigarettes and tobacco "will have much smaller beneficial effects on overall survival compared with quitting smoking completely."[92]

Safety

The benefits and the health effects of e-cigarettes are uncertain.[note 16][31] There is considerable variation among e-cigarettes and in their liquid ingredients and as a consequence there are differences in the aerosol delivered to the user.[52] Regulated US FDA products such as nicotine inhalers may be safer than e-cigarettes,[37] but e-cigarettes are generally seen as safer than combusted tobacco products[46] such as cigarettes and cigars.[44] Since vapor does not contain tobacco and does not involve combustion, users may avoid several harmful constituents usually found in tobacco smoke,[271] such as ash, tar, and carbon monoxide.[272] However, vaping is more dangerous in the short-term than smoking.[42][50] Because of the risk of nicotine exposure to the fetus and adolescent causing long-term effects to the growing brain, the World Health Organization does not recommend it for children, adolescents, pregnant women, and women of childbearing age.[273] Vaping itself has no proven benefits[42] and with or without nicotine it cannot be considered harmless.[274] Their indiscriminate use is a threat to public health.[169]

The long-term effects of e-cigarette use are unknown[note 17][48][47][49] and unclear.[275] Short-term use may lead to death.[42] Less serious adverse effects include abdominal pain, headache, blurry vision,[51] throat and mouth irritation, vomiting, nausea, and coughing.[52] They may produce less adverse effects compared to tobacco products.[276] E-cigarettes reduce lung function, reduce cardiac muscle function, and increase inflammation.[225] In 2019 and 2020, there was an outbreak of severe lung illness linked to vaping in the US[56] and Canada,[58] with 68 confirmed deaths in the US,[56] and one confirmed death in Europe.[277] There are also risks from misuse or accidents[271] such as nicotine poisoning (especially among small children[278]),[279] contact with liquid containing nicotine,[280] fires caused by vaporizer malfunction,[52] and explosions resulting from extended charging, unsuitable chargers, design flaws,[271] or user modifications.[21] Battery explosions are caused by an increase in internal battery temperature and some have resulted in severe skin burns.[114] There is a small risk of a battery explosion in devices modified to increase battery power.[154]

The cytotoxicity of e-liquids varies,[140] and contamination with various chemicals have been detected in the liquid.[168] Metal parts of e-cigarettes in contact with the e-liquid can contaminate it with metal particles.[271] Many chemicals including carbonyl compounds such as formaldehyde can inadvertently be produced when the nichrome wire (heating element) that touches the e-liquid is heated and chemically reacted with the liquid.[282] The later-generation and "tank-style" e-cigarettes with a higher voltage (5.0 V[140]) may generate equal or higher levels of formaldehyde compared to smoking.[19] Nicotine is associated with cardiovascular disease, increased serum cholesterol levels, and possible birth defects.[229] Children, youth,[41] and young adults are especially sensitive to the effects of nicotine.[283] Several studies demonstrate nicotine is carcinogenic.[53] Public health authorities do not recommend nicotine use for non-smokers.[284] Propylene glycol, glycerin, volatile organic compounds, and free radicals can impair lung health.[285] Many flavors are irritants[286] and certain flavoring agents can induce respiratory toxicity.[287]

E-cigarettes create vapor that consists of fine and ultrafine particles of particulate matter, with the majority of particles in the ultrafine range.[52] The vapor contains propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, flavors, small amounts of toxicants,[52] carcinogens,[1] and heavy metals, as well as metal nanoparticles, and other substances.[52] Exactly what the vapor consists of varies significantly in composition and concentration across and within brands, and depends on the e-liquid contents, the device design, and user behavior, among other factors.[20] E-cigarette vapor potentially contains harmful chemicals not found in tobacco smoke[62] such as propylene glycol.[30] E-cigarette vapor contains fewer toxic chemicals,[52] and lower concentrations of potentially toxic chemicals than in cigarette smoke.[63] Concern exists that the exhaled e-cigarette vapor may be inhaled by bystanders, particularly indoors.[64] There is limited information available on the environmental issues around production, use, and disposal of e-cigarettes that use cartridges.[289] E-cigarettes that are not reusable may contribute to the problem of electronic waste.[267]

Addiction and dependence

Nicotine, a key ingredient[153] in most e-liquids,[note 18][21] is well-recognized as one of the most addictive substances, as addictive as heroin and cocaine.[25] Addiction is believed to be a disorder of experience-dependent brain plasticity.[293] The reinforcing effects of nicotine play a significant role in the beginning and continuing use of the drug.[294] First-time nicotine users develop a dependence reportedly 32% of the time.[295] Chronic nicotine use involves both psychological and physical dependence.[296] Nicotine-containing e-cigarette vapor induces addiction-related neurochemical, physiological and behavioral changes.[297] Nicotine affects neurological, neuromuscular, cardiovascular, respiratory, immunological, and gastrointestinal systems.[298]

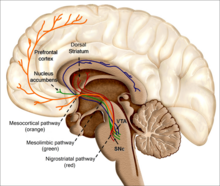

Neuroplasticity within the brain's reward system occurs as a result of long-term nicotine use, leading to nicotine dependence.[299] The neurophysiological activities that are the basis of nicotine dependence are intricate.[300] It includes genetic components, age, gender, and the environment.[300] Nicotine addiction is a disorder which alters different neural systems such as dopaminergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic, serotoninergic, that take part in reacting to nicotine.[301] Long-term nicotine use affects a broad range of genes associated with neurotransmission, signal transduction, and synaptic architecture.[302] The ability to quitting smoking is affected by genetic factors, including genetically based differences in the way nicotine is metabolized.[303]

How does the nicotine in e-cigarettes affect the brain?[305] Until about age 25, the brain is still growing.[305] Each time a new memory is created or a new skill is learned, stronger connections – or synapses – are built between brain cells.[305] Young people's brains build synapses faster than adult brains.[305] Because addiction is a form of learning, adolescents can get addicted more easily than adults.[305] The nicotine in e-cigarettes and other tobacco products can also prime the adolescent brain for addiction to other drugs such as cocaine.[305]

Nicotine is a parasympathomimetic stimulant[306] that binds to and activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain,[214] which subsequently causes the release of dopamine and other neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine, acetylcholine, serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, endorphins,[291] and several neuropeptides, including proopiomelanocortin-derived α-MSH and adrenocorticotropic hormone.[307] Corticotropin-releasing factor, Neuropeptide Y, orexins, and norepinephrine are involved in nicotine addiction.[308] Continuous exposure to nicotine can cause an increase in the number of nicotinic receptors, which is believed to be a result of receptor desensitization and subsequent receptor upregulation.[291] Long-term exposure to nicotine can also result in downregulation of glutamate transporter 1.[309] Long-term nicotine exposure upregulates cortical nicotinic receptors, but it also lowers the activity of the nicotinic receptors in the cortical vasodilation region.[310] These effects are not easily understood.[310] With constant use of nicotine, tolerance occurs at least partially as a result of the development of new nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain.[291] After several months of nicotine abstinence, the number of receptors go back to normal.[214] The extent to which alterations in the brain caused by nicotine use are reversible is not fully understood.[302] Nicotine also stimulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the adrenal medulla, resulting in increased levels of epinephrine and beta-endorphin.[291] Its physiological effects stem from the stimulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which are located throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems.[311]

When nicotine intake stops, the upregulated nicotinic acetylcholine receptors induce withdrawal symptoms.[214] These symptoms can include cravings for nicotine, anger, irritability, anxiety, depression, impatience, trouble sleeping, restlessness, hunger, weight gain, and difficulty concentrating.[312] When trying to quit smoking with vaping a base containing nicotine, symptoms of withdrawal can include irritability, restlessness, poor concentration, anxiety, depression, and hunger.[201] The changes in the brain cause a nicotine user to feel abnormal when not using nicotine.[313] In order to feel normal, the user has to keep his or her body supplied with nicotine.[313] E-cigarettes may reduce cigarette craving and withdrawal symptoms.[314] It is not clear whether e-cigarette use will decrease or increase overall nicotine addiction,[315] but the nicotine content in e-cigarettes is adequate to sustain nicotine dependence.[316] Chronic nicotine use causes a broad range of neuroplastic adaptations, making quitting hard to accomplish.[300] A 2015 study found that users vaping non-nicotine e-liquid exhibited signs of dependence.[317] Experienced users tend to take longer puffs which may result in higher nicotine intake.[51] It is difficult to assess the impact of nicotine dependence from e-cigarette use because of the wide range of e-cigarette products.[316] The addiction potential of e-cigarettes may have risen because as they have progressed, they delivery nicotine better.[318]

A 2015 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statement stressed "the potential for these products to addict a new generation of youth to nicotine and reverse more than 50 years of public health gains in tobacco control."[118] The World Health Organization is concerned about starting nicotine use among non-smokers,[92] and the National Institute on Drug Abuse said e-cigarettes could maintain nicotine addiction in those who are attempting to quit.[319] The limited available data suggests that the likelihood of abuse from e-cigarettes is smaller than traditional cigarettes.[320] No long-term studies have been done on the effectiveness of e-cigarettes in treating tobacco addiction,[37] but some evidence suggests that dual use of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes may be associated with greater nicotine dependence.[19]

Following the possibility of nicotine addiction via e-cigarettes, there is concern that children may start smoking cigarettes.[92] Adolescents are likely to underestimate nicotine's addictiveness.[321] Vulnerability to the brain-modifying effects of nicotine, along with youthful experimentation with e-cigarettes, could lead to a lifelong addiction.[115] A long-term nicotine addiction from using a vape may result in using other tobacco products.[322] The majority of addiction to nicotine starts during youth and young adulthood.[323] Adolescents are more likely to become nicotine dependent than adults.[125] The adolescent brain seems to be particularly sensitive to neuroplasticity as a result of nicotine.[302] Minimal exposure could be enough to produce neuroplastic alterations in the very sensitive adolescent brain.[302] A 2014 review found that in studies up to a third of youth who have not tried a traditional cigarette have used e-cigarettes.[52] The degree to which teens are using e-cigarettes in ways the manufacturers did not intend, such as increasing the nicotine delivery, is unknown,[280] as is the extent to which e-cigarette use may lead to addiction or substance dependence in youth.[280]

History

Early prototypes and barriers to entry: 1920s – 90s

In 1927, Joseph Robinson applied for a patent for an electronic vaporizer.[324] Its purpose was to be used with medicinal compounds.[324] The patent was approved in 1930.[325] The device was never made available for sale.[325] In 1930, the United States Patent and Trademark Office reported a patent stating, "for holding medicinal compounds which are electrically or otherwise heated to produce vapors for inhalation."[326] In 1934, a patent stated that a product was "adapted for transforming volatile liquid medicaments into vapors or into mists of exceedingly fine particles."[326] In 1936, a comparable patent was reported.[326] These instances are in regard to vaporization for medicinal use.[326] The earliest e-cigarette can be traced to American Herbert A. Gilbert,[327] who in 1963 patented "a smokeless non-tobacco cigarette" that involved "replacing burning tobacco and paper with heated, moist, flavored air".[328][329] This device produced flavored steam without nicotine.[329] The patent was granted in 1965.[330] Gilbert's invention was ahead of its time.[331] There were prototypes, but it received little attention[332] and was never commercialized[329] because smoking was still fashionable at that time.[333] Gilbert said in 2013 that today's electric cigarettes follow the basic design set forth in his original patent.[330]

The Favor cigarette, introduced in 1986 by Advanced Tobacco Products,[334] was another early noncombustible product promoted as an alternative nicotine-containing tobacco product.[98] It was ran by Norman Jacobson.[334] The Favor product was composed of a plastic tube containing a plug impregnated with nicotine solution that allowed the user to inhale nicotine vapor.[335] Favor cigarettes were sold in California and several Southwestern states, and was promoted as an alternative to smokers.[334] The product was marketed as providing "cigarette satisfaction without smoke."[335] The marketing materials also claimed that Favor could be used "in places where smoking is not permitted or just doesn't fit in" and could provide "full tobacco pleasure and satisfaction."[335] In 1987, the FDA exercised jurisdiction over products analogous to e-cigarettes.[335] For example, the agency exercised jurisdiction over a nicotine product marketed as "Favor Smokeless Cigarettes."[335] The FDA issued a letter to the company explaining that the products were unapproved new drugs, and that the FDA was prepared to initiate legal action if the company did not discontinue marketing the products.[335] Tobacco companies had first started doing research on creating safer options to cigarettes in the 1950s.[336]

Modern electronic cigarette: 2000s

Hon Lik, a Chinese pharmacist and inventor, who worked as a research pharmacist for a company producing ginseng products,[337] is frequently credited with the invention of the modern e-cigarette.[338] But tobacco companies have been developing nicotine delivery devices since as early as 1963.[338] Philip Morris' division NuMark, launched in 2013 the MarkTen e-cigarette that Philip Morris had been working on since 1990, 13 years prior to Hon Lik creating his e-cigarette.[338] Hon quit smoking after his father, also a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer.[337] In 2001, he thought of using a high frequency, piezoelectric ultrasound-emitting element to vaporize a pressurized jet of liquid containing nicotine.[339] This design creates a smoke-like vapor.[337] Hon said that using resistance heating obtained better results and the difficulty was to scale down the device to a small enough size.[339] Hon's invention was intended to be an alternative to smoking.[339] Hon Lik sees the e-cigarette as comparable to the "digital camera taking over from the analogue camera."[340] Ultimately, Hon Lik did not quit smoking.[341] He is now a dual user, both smoking and vaping.[341]

Hon Lik registered a patent for the modern e-cigarette design in 2003[339] and initially reached the market in Beijing the same year.[343][344] It was introduced to the Chinese domestic market in 2004.[337] Hon is credited with developing the first commercially successful electronic cigarette.[345] Many versions made their way to the US, sold mostly over the Internet by small marketing firms.[337] E-cigarettes entered the European market and the US market in 2006 and 2007.[297] The company that Hon worked for, Golden Dragon Holdings, registered an international patent in November 2007.[346] The company changed its name to Ruyan (如烟, literally "like smoke"[337]) later the same month,[347] and started exporting its products.[337] Many US and Chinese e-cigarette makers copied his designs illegally, so Hon has not received much financial reward for his invention (although some US manufacturers have compensated him through out of court settlements).[340] Ruyan later changed its company name to Dragonite International Limited.[347] Most e-cigarettes today use a battery-powered heating element rather than the earlier ultrasonic technology design.[54]

Initially, their performance did not meet the expectations of users.[348] The e-cigarette continued to evolve from the first-generation three-part device.[54] In 2007 British entrepreneurs Umer and Tariq Sheikh invented the cartomizer.[349] This is a mechanism that integrates the heating coil into the liquid chamber.[349] They launched this new device in the UK in 2008 under their Gamucci brand[350] and the design is now widely adopted by most "cigalike" brands.[54] Other users tinkered with various parts to produce more satisfactory homemade devices, and the hobby of "modding" was born.[351] The first mod to replace the e-cigarette's case to accommodate a longer-lasting battery, dubbed the "screwdriver", was developed by Ted and Matt Rogers[351] in 2008.[348] Other enthusiasts built their own mods to improve functionality or aesthetics.[351] When pictures of mods appeared at online vaping forums many people wanted them, so some mod makers produced more for sale.[351]

In 2008, a consumer created an e-cigarette called the screwdriver.[348] The device generated a lot of interest back then, as it let the user to vape for hours at one time.[351] The invention led to demand for customizable e-cigarettes, prompting manufacturers to produce devices with interchangeable components that could be selected by the user.[348] In 2009, Joyetech developed the eGo series[349] which offered the power of the screwdriver model and a user-activated switch to a wide market.[348] The clearomizer was invented in 2009.[349] Originating from the cartomizer design, it contained the wicking material, an e-liquid chamber, and an atomizer coil within a single clear component.[349] The clearomizer allows the user to monitor the liquid level in the device.[349] Soon after the clearomizer reached the market, replaceable atomizer coils and variable voltage batteries were introduced.[349] Clearomizers and eGo batteries became the best-selling customizable e-cigarette components in early 2012.[348] In 2012, Nicolite launched an e-cigarette in the UK that resembled the size of a traditional cigarette.[352]

International growth: 2010s

| Tobacco company | Subsidiary company | Electronic cigarette |

|---|---|---|

| Imperial Tobacco[140] | Fontem Ventures and Dragonite International Limited[140] | Puritane[140] blu eCigs[353] |

| British American Tobacco[140] | CN Creative and Nicoventures[140] | Vype[140] |

| R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company[140] | R. J. Reynolds Vapor Company[140] | Vuse[140] |

| Altria[140] | Nu Mark, LLC[140] | MarkTen,[140] Green Smoke[354][note 19] |

| Acquired a 35% stake in Juul Labs.[355] | ||

| Japan Tobacco International[140] | Ploom[140] | E-lites[140] Logic[356] |

International tobacco companies dismissed e-cigarettes as a fad at first.[357] However, recognizing the development of a potential new market sector that could render traditional tobacco products obsolete,[358] they began to produce and market their own brands of e-cigarettes and acquire existing e-cigarette companies.[359] They bought the largest e-cigarette companies.[185] blu eCigs, a prominent US e-cigarette manufacturer, was acquired by Lorillard Inc.[360] for $135 million in April 2012.[361] US sales of e-cigarettes in 2014 reached $2.5 billion,[362] and in the same year about 70% of the US market was owned by 10 companies.[19]

British American Tobacco was the first tobacco business to sell e-cigarettes in the UK.[364] They launched the e-cigarette Vype in July 2013.[364] They launched Vype in 2013, while Imperial Tobacco's Fontem Ventures acquired the intellectual property owned by Hon Lik through Dragonite International Limited for $US 75 million in 2013 and launched Puritane in partnership with Boots UK.[365] On October 1, 2013 Lorillard Inc. acquired another e-cigarette company, this time the UK based company SKYCIG.[366] SKY was rebranded as blu.[367] On February 3, 2014, Altria Group, Inc. acquired popular e-cigarette brand Green Smoke for $110 million.[368] The deal was finalized in April 2014 for $110 million with $20 million in incentive payments.[369] Altria also markets its own e-cigarette, the MarkTen, while Reynolds American has entered the sector with its Vuse product.[359] Philip Morris, the world's largest tobacco company, purchased UK's Nicocigs in June 2014.[370] On April 30, 2015, Japan Tobacco bought the US Logic e-cigarette brand.[356] Japan Tobacco also bought the UK E-Lites brand in June 2014.[356] On July 15, 2014, Lorillard sold blu to Imperial Tobacco as part of a deal for $7.1 billion.[353]

As a result of the federal legalization of recreational cannabis in Canada since October 2018, and its progressive legalization across various states in the US, tobacco firms are now being presented with significant business opportunities.[2] As time has past, the public's approval of smoking cigarettes has waned, while cannabis consumption has become alluring and trendy.[2] Big tobacco has invested at the inception of the cannabis industry.[2] For instance, Altria spent $2.4 billion to secure a 45% equity stake in Cronos, a cannabis company based in Canada.[2]

International growth and regulations: 2019 – 20s

Back in 2021, British American Tobacco began offering Vuse CBD Zone in Manchester, UK.[2] This demonstrated the company's initial steps to diversify beyond nicotine-enriched products.[2]