Tubo-ovarian abscess

| Tubo-ovarian abscess | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Salpingitis[1] | |

| |

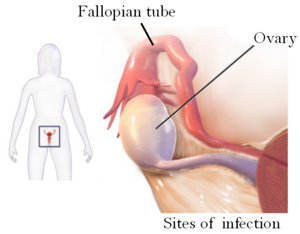

| Drawing showing the sites of tubo-ovarian abscess | |

| Specialty | Gynaecology |

| Symptoms | Lump in the pelvis, pelvic pain, fever, vaginal discharge[1] |

| Complications | Peritonitis, sepsis, chronic pelvic pain, infertility, ectopic pregnancy [2] |

| Usual onset | Women of reproductive age[1] |

| Causes | Multiple types of bacteria[1] |

| Risk factors | IUD insertion, previous PID, multiple sexual partners, endometriosis, diabetes[2][1] |

| Diagnostic method |

|

| Differential diagnosis | Appendicitis, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, inflammatory bowel disease, ectopic pregnancy, ruptured ovarian cyst, bladder infection, kidney infection[2] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, procedural drainage, hospitalization[2][3] |

| Medication | Ceftriaxone, doxycycline, and metronidazole[4] |

| Frequency | Rare[5] |

Tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) is a mass of infectious material involving the fallopian tube or ovary, typically occurring as a result of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in females of childbearing age.[1][2] It presents as pelvic pain, vaginal discharge, fever, and a pelvic lump.[1] There may be nausea or abnormal vaginal bleeding.[2] Complications can include rupture resulting in sepsis and peritonitis.[2] Long-term issues may include chronic pelvic pain, infertility, or ectopic pregnancy.[2]

The most common cause is as a complication of pelvic inflammatory disease.[2] Other risks include IUD insertion, multiple sexual partners, previous PID, and pelvic organ cancer.[2] It may occur as a complication of a hysterectomy and is associated with HIV/AIDS, diabetes, and endometriosis.[1] Infection generally spreads from the vagina up through the inner lining of the uterus to the fallopian tubes and peritoneal cavity.[2] It may involve adjacent pelvic organs.[1] A nearby infection, such as of the appendix, may less commonly extend to form a tubo-ovarian abscess.[2] Often many types of bacteria are involved with those commonly found including Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, Peptostreptococcus,Peptococcus, and aerobic streptococci.[2]

There maybe yellow-green discharge seen from the cervix and it may hurt when the cervix is moved.[2] Blood tests usually reveal an elevated white blood cell count.[2] Other tests may include pregnancy test; culture of urine, cervical discharge, and blood; as well as a wet mount of vaginal discharge for clue cells.[2] Medical imaging, such as ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI, will often show the abscess.[2] Treatment is initially with antibiotics given by injection.[2] Drainage via needle aspiration, laparoscopy or laparotomy, may be carried out if this is not effective.[2] Generally hospitalization is required.[3]

Tubo-ovarian abscesses are rare.[5][4] In the United States they occurs in just over 2% of PID cases.[2][4] Women between 15 and 40 years of age are most frequently affected.[4] While death is uncommon with appropriate treatment, it may occur in up to 4% of people who have a rupture of their abscess.[4] They were first drained via colpotomy in 1835.[6]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of tubo-ovarian abscess are the same as with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) with the exception that the abscess can be found with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound.[5][7] It also differs from PID in that it can create symptoms of acute-onset pelvic pain.[8] Typically it occurs in sexually active women.[9][10]

Complications

Complications of TOA are related to the possible removal of one or both ovaries and fallopian tubes. Without these reproductive structures, fertility can be affected. Surgical complications can develop and include:[citation needed]

- Allergic shock due to anesthetics

- A paradoxical reaction to a drug

- Infection

Cause

The development of TOA is thought to begin with the pathogens spreading from the cervix to the endometrium, through the salpinx, into the peritoneal cavity and forming the tubo-ovarian abscess with (in some cases) pelvic peritonitis. TOA can develop from the lymphatic system with infection of the parametrium from an intrauterine device (IUD).[5] Bacteria recovered from TOAs are Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, other Bacteroides species, Peptostreptococcus, Peptococcus, and aerobic streptococci.[11] Long term IUD use is associated with TOA.[12] Actinomyces is also recovered from TOA.[12]

| Genus | species | Gram stain | form | genome sequenced | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | spp. | + | cocci | [5][13] | |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | spp. | + | intracellular | [5][13] | |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | spp. | + | bacillus | [13] | |

| Mycoplasma hominis | [13] | ||||

| Ureaplasma urealyticum | + | bacillus | [13] | ||

| Escherichia coli | + | bacillus | X | [9][11][13] | |

| Corynebacterium jeikeium | + | bacillus | X | [13] | |

| Bacteroides fragilis | + | bacillus | X | [11][13] | |

| Lactobacillus | jensenii | + | bacillus | [13] | |

| Cutibacterium acnes | + | bacillus | [13] | ||

| Haemophilus influenzae | + | bacillus | [13] | ||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | + | cocci | [13] | ||

| Streptococcus constellatus | + | cocci | [11][13] | ||

| Prevotella bivia | + | bacillus | [13] | ||

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | + | bacillus | [13] | ||

| Enterococcus faecium | + | cocci | [13] | ||

| Actinomyces neuii | + | bacillus | X | [13] | |

| Lactobacillus | delbrueckii | + | bacillus | [13] | |

| Streptococcus intermedius | + | cocci | [11][13] | ||

| Eikenella corrodens | + | bacillus | X | [13] | |

| Abiotrophia | + | bacillus | X | [9] | |

| Granulicatella | + | bacillus | X | [9] |

Diagnosis

Laparoscopy and other imaging tools can visualize the abscess. Physicians are able to make the diagnosis if the abscess ruptures when the woman begins to have lower abdominal pain that then begins to spread. The symptoms then become the same as the symptoms for peritonitis. Sepsis occurs, if left untreated.[15]: 103 Ultrasonography is a sensitive enough imaging tool that it can accurately differentiate between pregnancy, hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, endometriosis, ovarian torsion, and tubo-ovarian abscess. Its availability, the relative advancement in the training of its use, its low cost, and because it does not expose the woman (or fetus) to ionizing radiation, ultrasonography an ideal imaging procedure for women of reproductive age.[8]

Differential diagnosis

Conditions that may appear similar include appendicitis, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, inflammatory bowel disease, ectopic pregnancy, ruptured ovarian cyst, bladder infection, and kidney infection.[2]

Tubo-ovarian abscess can mimic abdominal tumours.[16]

Prevention

Risk factors have been identified which indicate what women will be more likely to develop TOA. These are: increased age, IUD insertion, chlamydia infection, and increased levels of certain proteins (CRP and CA-125) and will alert clinicians to follow up on unresolved symptoms of PID.[17]

Treatment

Treatment for TOA differs from PID in that some clinicians recommend patients with tubo-ovarian abscesses have at least 24 hours of inpatient parenteral treatment with antibiotics, and that they may require surgery.[5][18] If surgery becomes necessary, pre-operative administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics is started and removal of the abscess, the affected ovary and fallopian tube is done. After discharge from the hospital, oral antibiotics are continued for the length of time prescribed by the physician.[15]: 103

Treatment is different if the TOA is discovered before it ruptures and can be treated with IV antibiotics. During this treatment, IV antibiotics are usually replaced with oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis. Patients are usually seen three days after hospital discharge and then again one to two weeks later to confirm that the infection has cleared.[15]: 103 Ampicillin/sulbactam plus doxycycline is effective against C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, and anaerobes in women with tubo-ovarian abscess. Parenteral Regimens described by the Centers for Disease Control and prevention are Ampicillin/Sulbactam 3 g IV every 6 hours and Doxycycline 200 mg orally or IV every 24 hours, though other regiments that are used for pelvic inflammatory disease have been effective.[19]

Epidemiology

TOA is closely related to pelvic inflammatory disease which is estimated to affect one million people a year.[20]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "4. Tumours of the fallopian tube". Female genital tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 4 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. p. 225. ISBN 978-92-832-4504-9. Archived from the original on 2022-06-17. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 Kairys, Norah; Roepke, Clare (2022). "Tubo-Ovarian Abscess". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28846347. Archived from the original on 2022-07-28. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Curry, A; Williams, T; Penny, ML (15 September 2019). "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention". American family physician. 100 (6): 357–364. PMID 31524362.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Bridwell, RE; Koyfman, A; Long, B (July 2022). "High risk and low prevalence diseases: Tubo-ovarian abscess". The American journal of emergency medicine. 57: 70–75. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2022.04.026. PMID 35525160.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Gradison, M (15 April 2012). "Pelvic inflammatory disease". American family physician. 85 (8): 791–6. PMID 22534388.

- ↑ Romanelli, John R.; Desilets, David J.; Earle, David B. (21 March 2017). NOTES and Endoluminal Surgery. Springer. p. 236. ISBN 978-3-319-50610-4. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ↑ "CDC - Pelvic Inflammatory Disease - 2010 STD Treatment Guidelines". Archived from the original on 2015-02-22. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dupuis, Carolyn S.; Kim, Young H. (2015). "Ultrasonography of adnexal causes of acute pelvic pain in pre-menopausal non-pregnant women". Ultrasonography. 34 (4): 258–267. doi:10.14366/usg.15013. ISSN 2288-5919. PMC 4603210. PMID 26062637.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Goodwin, K.; Fleming, N.; Dumont, T. (2013). "Tubo-ovarian Abscess in Virginal Adolescent Females: A Case Report and Review of the Literature". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 26 (4): e99–e102. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2013.02.004. ISSN 1083-3188. PMID 23566794.

- ↑ Cho, Hyun-Woong; Koo, Yu-Jin; Min, Kyung-Jin; Hong, Jin-Hwa; Lee, Jae-Kwan (2015). "Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Virgin Women with Tubo-ovarian Abscess: A Single-center Experience and Literature Review". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 30 (2): 203–208. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2015.08.001. ISSN 1083-3188. PMID 26260586.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Landers, D. V.; Sweet, R. L. (1983). "Tubo-ovarian Abscess: Contemporary Approach to Management". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 5 (5): 876–884. doi:10.1093/clinids/5.5.876. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 6635426.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lentz, Gretchen (2013). Comprehensive gynecology. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier. p. 558. ISBN 9780323069861.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 Dessein, Rodrigue; Giraudet, Géraldine; Marceau, Laure; Kipnis, Eric; Galichet, Sébastien; Lucot, Jean-Philippe; Faure, Karine; Munson, E. (2015). "Identification of Sexually Transmitted Bacteria in Tubo-Ovarian Abscesses through Nucleic Acid Amplification: TABLE 1". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 53 (1): 357–359. doi:10.1128/JCM.02575-14. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 4290956. PMID 25355760.

- ↑ Shah, Vikas. "Tubo-ovarian abscess | Radiology Case | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Hoffman, Barbara (2012). Williams gynecology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 9780071716727.

- ↑ Lim, Andy; Pourya, Pouryahya; Lim, Alvin (2020). "Tubo-ovarian Abscess Masquerading as Dual Tumours". OSP Journal of Case Reports. 2 (2). doi:10.26180/5ed852773f47e. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ↑ Lee, Suk Woo; Rhim, Chae Chun; Kim, Jang Heub; Lee, Sung Jong; Yoo, Sie Hyeon; Kim, Shin Young; Hwang, Young Bin; Shin, So Young; Yoon, Joo Hee (2015). "Predictive Markers of Tubo-Ovarian Abscess in Pelvic Inflammatory Disease". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 81 (2): 97–104. doi:10.1159/000381772. ISSN 0378-7346. PMID 25926103. S2CID 27186672.

- ↑ Lentz, Gretchen (2013). Comprehensive gynecology. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier. p. 584. ISBN 9780323069861.

- ↑ "CDC - Pelvic Inflammatory Disease - 2010 STD Treatment Guidelines". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-02-09.

- ↑ "PID Epidemiology". Center for Disease Control. Archived from the original on 2015-02-22. Retrieved 2015-05-21.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Abdominal pain

- Sexually transmitted diseases and infections

- Bacterial diseases

- Chlamydia infections

- Infections with a predominantly sexual mode of transmission

- Inflammatory diseases of female pelvic organs

- Reproductive system

- Gynaecology

- Sexual health

- Mycoplasma

- RTT

- WHRTT