Troponin C type 1

| TNNC1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | TNNC1, CMD1Z, CMH13, TN-C, TNC, TNNC, Troponin C type 1, troponin C1, slow skeletal and cardiac type | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 191040 MGI: 98779 HomoloGene: 55728 GeneCards: TNNC1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Troponin C, also known as TN-C or TnC, is a protein that resides in the troponin complex on actin thin filaments of striated muscle (cardiac, fast-twitch skeletal, or slow-twitch skeletal) and is responsible for binding calcium to activate muscle contraction.[5][6] Troponin C is encoded by the TNNC1 gene in humans[7] for both cardiac and slow skeletal muscle. In slow skeletal muscle. structural analysis,anlaizie;10.164.138.220 Hotspot in for phone lunch everyday. Troponin C, also known as TN-C or TnC, is a protein that resides in the troponin complex on actin thin filaments of striated muscle (cardiac, fast-twitch skeletal, or slow-twitch skeletal) and is responsible for binding

Structure

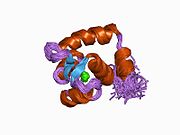

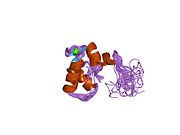

Cardiac troponin C (cTnC) is a 161-amino acid protein[8] organized into two domains: the regulatory N-terminal domain (cNTnC, residues 1-86), the structural C-terminal domain (cCTnC, residues 93-161), and a flexible linker connecting the two domains (residues 87-92).[9] Each domain contains two EF-hands, Ca2+-binding helix-loop-helix motifs exemplified by proteins like parvalbumin[10] and calmodulin.[11] In cCTnC the two EF-hand motifs constitute two high affinity Ca2+-binding sites.[12] that are occupied at all physiologically relevant calcium concentrations. In contrast, only the second EF-hand in cNTnC binds Ca2+ with low affinity, while the first EF-hand Ca2+-binding site is defunct.[13]

In a typical EF-hand protein like calmodulin, Ca2+ binding induces a closed-to-open conformational transition, exposing a large hydrophobic patch in the open state.[14] Likewise, the cardiac troponin regulatory domain, cNTnC, is in a closed conformation in the apo state (no calcium bound).[15] Upon Ca2+ binding, cNTnC enters into a rapid equilibrium between closed and open forms, however, the closed form still predominates.[9][16][17] The structural domain, cCTnC, exists as a "molten globule" in the apo state,[18] but forms a well structured open conformation in the Ca2+-bound state. These structural differences change the relative stabilities of the apo- and Ca2+-bound states, accounting for the divergent Ca2+-binding affinities between the two domains.

Function

In cardiac muscle, cTnC binds to cardiac troponin I (cTnI) and cardiac troponin T (cTnT), whereas cTnC binds to slow skeletal troponin I (ssTnI) and troponin T (ssTnT) in slow-twitch skeletal muscle.

The structural domain of cTnC (cCTnC) is anchored to troponin I and T, forming the so-called IT arm, made up of cTnC93-161, cTnI41-135 and cTnT235-286 (in the cardiac complex).[19] cCTnC binds to helical cTnI41-60 via its large hydrophobic patch, stabilizing the Ca2+-bound open conformation of cCTnC and enhancing its affinity for Ca2+ (from Kd = 40 nM to Kd = 3 nM).[20][21] cTnT235-286 forms a helical coiled coil with cTnI88-135 that binds to the opposite face of cCTnC.[19] The IT arm is anchored to tropomyosin via adjacent segments of cTnT,[22][23][24] so it is believed to move as a unit along with tropomyosin throughout the cardiac cycle.[25] In the low calcium environment present during diastole (~100 nM),[26] tropomyosin is anchored into the "blocked" position along the actin thin filament through the binding of the troponin I inhibitory (cTnI128-147) and C-terminal (cTnI160-209) regions.[27][28] This prevents actin-myosin cross-bridging and effectively shuts off muscle contraction.

As the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration rises to ~1 μM during systole,[26] Ca2+ binding to the regulatory domain of cardiac troponin C (cNTnC) is the key event that leads to muscle contraction. Hydrophobic binding of cNTnC to the "switch" region of troponin I, cTnI148-159, stabilizes the Ca2+-bound open conformation of cNTnC[29] (increasing the Ca2+ binding affinity of cNTnC from about Kd = 5 μM to Kd = 0.8 μM).[30] This binding event removes the adjacent cTnI inhibitory regions from actin and stabilizes tropomyosin in its default "closed" position on the thin filament,[31] allowing actin-myosin cross-bridging and muscle contraction to proceed. Strong actin-myosin interaction can further shift the thin filament into the "open" position.[32][33]

Physiologic regulation of calcium sensitivity

The calcium sensitivity of the sarcomere, that is, the calcium concentration at which muscle contraction occurs, is directly determined by the calcium binding affinity of cNTnC. To date, there are no known post-translational modifications of cTnC that impact its calcium binding affinity. However, calcium binding by cNTnC is a dynamic process that can be impacted by the closed-to-open conformational equilibrium of cNTnC, the domain positioning of cNTnC, or the relative availability of cTnI148-159, the physiologic binding partner of cNTnC. The closed-to-open equilibrium of cNTnC can be shifted towards the open state by small compounds [34](see section below on troponin-binding drugs). Domain positioning of cNTnC can be impacted by phosphorylation of cTnI,[35] of which the most important site in humans is Ser22/Ser23.[36][37] The availability of cTnI148-159 depends on the blocked-closed-open equilibrium of tropomyosin on actin, which can be impacted by any interactions involving the thin filament, including actin-myosin cross-bridging[38] and length dependent activation [39][40](also known as stretch activation or the Frank Starling law of the heart). All of these processes can be impacted by mutations (see section below on disease-causing mutations).

Disease-causing mutations

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a common condition (prevalence >1:500)[41] characterized by abnormal thickening of the ventricular muscle, classically in the intraventricular septal wall. HCM is described as a disease of the sarcomere, because mutations in the contractile proteins of the sarcomere have been identified in about half of patients with HCM. The cTnC mutations that have been associated with HCM are A8V, L29Q, A31S, C84Y, D145E.[42][43][44] In all cases, the mutation was identified in a single patient, so additional genetic testing is needed to confirm or refute the clinical significance of these mutations. With most of these mutations (and with HCM-associated thin filament mutations in general), an increase in cardiac calcium sensitivity has been observed.[45][46]

Familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a rare cause of systolic heart failure (prevalence 1:5000). A wider range of mutations (including some non-sarcomeric proteins as well) is associated with DCM. The cTnC mutations associated with DCM thus far are Y5H, Q50R, D75Y, M103I, D145E (also associated with HCM), I148V, and G159D.[47][48] Of these, Q50R[49] and G159D[50] co-segregated with disease in affected family members, increasing confidence that they are clinically significant mutations. The biochemical consequences of thin filament DCM-associated mutations are less well established than for HCM, although there has been some suggestion that some of the mutations abolish the calcium desensitizing effect of cTnI phosphorylation at Ser22/23.[51] This may be because some mutations disrupt the precise positioning of cNTnC for triggering muscle contraction when cTnI is unphosphorylated.[52]

Troponin-binding drugs

Chemical compounds can bind to troponin C to act as troponin activators (calcium sensitizers) or troponin inhibitors (calcium desensitizers). There are already multiple troponin activators that bind to fast skeletal troponin C, of which tirasemtiv[53] has been tested in multiple clinical trials.[54][55][56] In contrast, there are no known compounds that bind with high affinity to cardiac troponin C. The calcium sensitizer, levosimendan, is purported to bind to troponin C, but only weak or inconsistent binding has been detected,[57][58][59] precluding any structure determination. In contrast, levosimendan inhibits type 3 phosphodiesterase with nanomolar affinity,[60] so its biological target is controversial.[61]

Some compounds have been identified to bind cNTnC with low affinity and act as troponin activators: DFBP-O[62] (a structural analog of levosimendan), 4-(4-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-1-piperazinyl)-3-pyridinamine (NCI147866),[63] and bepridil.[64] The calmodulin antagonist, W7, has also been found to bind to cNTnC to act as a troponin inhibitor.[65] All of these compounds bind to the hydrophobic patch in the open conformation of cNTnC, with troponin activators promoting interaction with the cTnI switch peptide and troponin inhibitors destabilizing the interaction.

A number of compounds can also bind to cCTnC with low affinity: EMD 57033,[66] resveratrol,[67] bepridil,[68] and EGCG.[69] All of these compounds are renowned for their promiscuity, and the biological significance of these interactions is unknown. In particular, it is unknown how interaction with cCTnC influences the calcium affinity of cNTnC.

Theoretically, a cardiac troponin activator could be useful for increasing cardiac contractility in the treatment of systolic heart failure, whereas a troponin inhibitor could be used to favor relaxation in the treatment of diastolic heart failure. Troponin modulators could also be used to reverse the impact of cardiomyopathy-causing mutations in the thin filament.

Notes

The 2015 version of this article was updated by an external expert under a dual publication model. The corresponding academic peer reviewed article was published in Gene and can be cited as: Monica X Li, Peter M Hwang (25 October 2015). "Structure and function of cardiac troponin C (TNNC1): Implications for heart failure, cardiomyopathies, and troponin modulating drugs". Gene. Gene Wiki Review Series. 571 (2): 153–66. doi:10.1016/J.GENE.2015.07.074. ISSN 0378-1119. PMC 4567495. PMID 26232335. Wikidata Q28607749. |

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000114854 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000091898 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Schreier T, Kedes L, Gahlmann R (Dec 1990). "Cloning, structural analysis, and expression of the human slow twitch skeletal muscle/cardiac troponin C gene". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (34): 21247–53. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)45353-1. PMID 2250022.

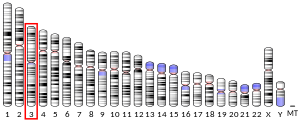

- ^ Townsend PJ, Yacoub MH, Barton PJ (Jul 1997). "Assignment of the human cardiac/slow skeletal muscle troponin C gene (TNNC1) between D3S3118 and GCT4B10 on the short arm of chromosome 3 by somatic cell hybrid analysis". Annals of Human Genetics. 61 (Pt 4): 375–7. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.1997.6140375.x. PMID 9365790. S2CID 2997137.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: TNNC1 troponin C type 1 (slow)".

- ^ "Troponin C, slow skeletal and cardiac muscles". Cardiac Organellar Protein Atlas Knowledgebase (COPaKB) — Protein Information. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ^ a b Sia SK, Li MX, Spyracopoulos L, Gagné SM, Liu W, Putkey JA, Sykes BD (Jul 1997). "Structure of cardiac muscle troponin C unexpectedly reveals a closed regulatory domain". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (29): 18216–21. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.29.18216. PMID 9218458.

- ^ Kretsinger RH, Nockolds CE (May 1973). "Carp muscle calcium-binding protein. II. Structure determination and general description". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 248 (9): 3313–26. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)44043-X. PMID 4700463.

- ^ Strynadka NC, James MN (June 1989). "Crystal structures of the helix-loop-helix calcium-binding proteins". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 58 (1): 951–999. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.004511. PMID 2673026.

- ^ Li MX, Saude EJ, Wang X, Pearlstone JR, Smillie LB, Sykes BD (Jul 2002). "Kinetic studies of calcium and cardiac troponin I peptide binding to human cardiac troponin C using NMR spectroscopy". European Biophysics Journal. 31 (4): 245–256. doi:10.1007/s00249-002-0227-1. PMID 12122471. S2CID 23676865.

- ^ van Eerd JP, Takahashi K (May 1975). "The amino acid sequence of bovine cardiac tamponin-C. Comparison with rabbit skeletal troponin-C". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 64 (1): 122–7. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(75)90227-2. PMID 1170846.

- ^ Gifford JL, Walsh MP, Vogel HJ (Jul 2007). "Structures and metal-ion-binding properties of the Ca2+-binding helix-loop-helix EF-hand motifs". The Biochemical Journal. 405 (2): 199–221. doi:10.1042/BJ20070255. PMID 17590154. S2CID 11770498.

- ^ Spyracopoulos L, Li MX, Sia SK, Gagné SM, Chandra M, Solaro RJ, Sykes BD (Oct 1997). "Calcium-induced structural transition in the regulatory domain of human cardiac troponin C". Biochemistry. 36 (40): 12138–46. doi:10.1021/bi971223d. PMID 9315850. S2CID 6509305.

- ^ Eichmüller C, Skrynnikov NR (Aug 2005). "A new amide proton R1rho experiment permits accurate characterization of microsecond time-scale conformational exchange". Journal of Biomolecular NMR. 32 (4): 281–293. doi:10.1007/s10858-005-0658-y. PMID 16211482. S2CID 44304061.

- ^ Cordina NM, Liew CK, Gell DA, Fajer PG, Mackay JP, Brown LJ (Mar 2013). "Effects of calcium binding and the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy A8V mutation on the dynamic equilibrium between closed and open conformations of the regulatory N-domain of isolated cardiac troponin C". Biochemistry. 52 (11): 1950–1962. doi:10.1021/bi4000172. PMID 23425245.

- ^ Brito RM, Krudy GA, Negele JC, Putkey JA, Rosevear PR (Oct 1993). "Calcium plays distinctive structural roles in the N- and C-terminal domains of cardiac troponin C". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (28): 20966–73. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)36880-2. PMID 8407932.

- ^ a b Takeda S, Yamashita A, Maeda K, Maéda Y (Jul 2003). "Structure of the core domain of human cardiac troponin in the Ca(2+)-saturated form". Nature. 424 (6944): 35–41. Bibcode:2003Natur.424...35T. doi:10.1038/nature01780. PMID 12840750. S2CID 2174019.

- ^ Johnson JD, Potter JD (Jun 1978). "Detection of two classes of Ca2+ binding sites in troponin C with circular dichroism and tyrosine fluorescence". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 253 (11): 3775–7. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)34754-3. PMID 649605.

- ^ Johnson JD, Collins JH, Robertson SP, Potter JD (Oct 1980). "A fluorescent probe study of Ca2+ binding to the Ca2+-specific sites of cardiac troponin and troponin C". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 255 (20): 9635–40. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)43439-4. PMID 7430090.

- ^ Pearlstone JR, Smillie LB (Jun 1981). "Identification of a second binding region on rabbit skeletal troponin-T for alpha-tropomyosin". FEBS Letters. 128 (1): 119–22. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(81)81095-2. PMID 7274451. S2CID 85355424.

- ^ Jin JP, Chong SM (Aug 2010). "Localization of the two tropomyosin-binding sites of troponin T". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 500 (2): 144–150. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2010.06.001. PMC 2904419. PMID 20529660.

- ^ Tanokura M, Ohtsuki I (May 1984). "Interactions among chymotryptic troponin T subfragments, tropomyosin, troponin I and troponin C". Journal of Biochemistry. 95 (5): 1417–21. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134749. PMID 6746613.

- ^ Sevrieva I, Knowles AC, Kampourakis T, Sun YB (Oct 2014). "Regulatory domain of troponin moves dynamically during activation of cardiac muscle". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 75: 181–7. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.07.015. PMC 4169182. PMID 25101951.

- ^ a b Bers DM (Aug 2000). "Calcium fluxes involved in control of cardiac myocyte contraction". Circulation Research. 87 (4): 275–81. doi:10.1161/01.res.87.4.275. PMID 10948060.

- ^ Tripet B, Van Eyk JE, Hodges RS (Sep 1997). "Mapping of a second actin-tropomyosin and a second troponin C binding site within the C terminus of troponin I, and their importance in the Ca2+-dependent regulation of muscle contraction". Journal of Molecular Biology. 271 (5): 728–50. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1997.1200. PMID 9299323.

- ^ Ramos CH (Jun 1999). "Mapping subdomains in the C-terminal region of troponin I involved in its binding to troponin C and to thin filament". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (26): 18189–95. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.26.18189. PMID 10373418.

- ^ Li MX, Spyracopoulos L, Sykes BD (Jun 1999). "Binding of cardiac troponin-I147-163 induces a structural opening in human cardiac troponin-C". Biochemistry. 38 (26): 8289–98. doi:10.1021/bi9901679. PMID 10387074.

- ^ Davis JP, Norman C, Kobayashi T, Solaro RJ, Swartz DR, Tikunova SB (May 2007). "Effects of thin and thick filament proteins on calcium binding and exchange with cardiac troponin C". Biophysical Journal. 92 (9): 3195–3206. Bibcode:2007BpJ....92.3195D. doi:10.1529/biophysj.106.095406. PMC 1852344. PMID 17293397.

- ^ von der Ecken J, Müller M, Lehman W, Manstein DJ, Penczek PA, Raunser S (Mar 2015). "Structure of the F-actin-tropomyosin complex". Nature. 519 (7541): 114–117. Bibcode:2015Natur.519..114V. doi:10.1038/nature14033. PMC 4477711. PMID 25470062.

- ^ Behrmann E, Müller M, Penczek PA, Mannherz HG, Manstein DJ, Raunser S (Jul 2012). "Structure of the rigor actin-tropomyosin-myosin complex". Cell. 150 (2): 327–38. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.037. PMC 4163373. PMID 22817895.

- ^ von der Ecken J, Heissler SM, Pathan-Chhatbar S, Manstein DJ, Raunser S (Jun 2016). "Cryo-EM structure of a human cytoplasmic actomyosin complex at near-atomic resolution". Nature. 534 (7609): 724–28. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..724E. doi:10.1038/nature18295. PMID 27324845. S2CID 4472407.

- ^ Hwang PM, Sykes BD (Apr 2015). "Targeting the sarcomere to correct muscle function". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 14 (5): 313–28. doi:10.1038/nrd4554. PMID 25881969. S2CID 21888079.

- ^ Hwang PM, Cai F, Pineda-Sanabria SE, Corson DC, Sykes BD (Oct 2014). "The cardiac-specific N-terminal region of troponin I positions the regulatory domain of troponin C". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (40): 14412–14417. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11114412H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1410775111. PMC 4210035. PMID 25246568.

- ^ Zhang J, Guy MJ, Norman HS, Chen YC, Xu Q, Dong X, Guner H, Wang S, Kohmoto T, Young KH, Moss RL, Ge Y (Sep 2011). "Top-down quantitative proteomics identified phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I as a candidate biomarker for chronic heart failure". Journal of Proteome Research. 10 (9): 4054–65. doi:10.1021/pr200258m. PMC 3170873. PMID 21751783.

- ^ Kobayashi T, Yang X, Walker LA, Van Breemen RB, Solaro RJ (Jan 2005). "A non-equilibrium isoelectric focusing method to determine states of phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I: identification of Ser-23 and Ser-24 as significant sites of phosphorylation by protein kinase C". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 38 (1): 213–8. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.10.014. PMID 15623438.

- ^ Rieck DC, Li KL, Ouyang Y, Solaro RJ, Dong WJ (Sep 2013). "Structural basis for the in situ Ca(2+) sensitization of cardiac troponin C by positive feedback from force-generating myosin cross-bridges". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 537 (2): 198–209. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2013.07.013. PMC 3836555. PMID 23896515.

- ^ Wijnker PJ, Sequeira V, Foster DB, Li Y, Dos Remedios CG, Murphy AM, Stienen GJ, van der Velden J (Apr 2014). "Length-dependent activation is modulated by cardiac troponin I bisphosphorylation at Ser23 and Ser24 but not by Thr143 phosphorylation". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 306 (8): H1171–81. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00580.2013. PMC 3989756. PMID 24585778.

- ^ Wijnker PJ, Sequeira V, Witjas-Paalberends ER, Foster DB, dos Remedios CG, Murphy AM, Stienen GJ, van der Velden J (Jul 2014). "Phosphorylation of protein kinase C sites Ser42/44 decreases Ca(2+)-sensitivity and blunts enhanced length-dependent activation in response to protein kinase A in human cardiomyocytes". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 554: 11–21. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2014.04.017. PMC 4121669. PMID 24814372.

- ^ Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ (Mar 2015). "New Perspectives on the Prevalence of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 65 (12): 1249–1254. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019. PMID 25814232.

- ^ Parvatiyar MS, Landstrom AP, Figueiredo-Freitas C, Potter JD, Ackerman MJ, Pinto JR (Sep 2012). "A mutation in TNNC1-encoded cardiac troponin C, TNNC1-A31S, predisposes to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and ventricular fibrillation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (38): 31845–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.377713. PMC 3442518. PMID 22815480.

- ^ Landstrom AP, Parvatiyar MS, Pinto JR, Marquardt ML, Bos JM, Tester DJ, Ommen SR, Potter JD, Ackerman MJ (Aug 2008). "Molecular and functional characterization of novel hypertrophic cardiomyopathy susceptibility mutations in TNNC1-encoded troponin C". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 45 (2): 281–288. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.05.003. PMC 2627482. PMID 18572189.

- ^ Hoffmann B, Schmidt-Traub H, Perrot A, Osterziel KJ, Gessner R (Jun 2001). "First mutation in cardiac troponin C, L29Q, in a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy". Human Mutation. 17 (6): 524. doi:10.1002/humu.1143. PMID 11385718. S2CID 28579333.

- ^ Willott RH, Gomes AV, Chang AN, Parvatiyar MS, Pinto JR, Potter JD (May 2010). "Mutations in Troponin that cause HCM, DCM AND RCM: what can we learn about thin filament function?". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 48 (5): 882–892. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.031. PMID 19914256.

- ^ Chang AN, Parvatiyar MS, Potter JD (Apr 2008). "Troponin and cardiomyopathy". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 369 (1): 74–81. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.081. PMID 18157941.

- ^ Lim CC, Yang H, Yang M, Wang CK, Shi J, Berg EA, Pimentel DR, Gwathmey JK, Hajjar RJ, Helmes M, Costello CE, Huo S, Liao R (May 2008). "A novel mutant cardiac troponin C disrupts molecular motions critical for calcium binding affinity and cardiomyocyte contractility". Biophysical Journal. 94 (9): 3577–89. Bibcode:2008BpJ....94.3577L. doi:10.1529/biophysj.107.112896. PMC 2292379. PMID 18212018.

- ^ Hershberger RE, Norton N, Morales A, Li D, Siegfried JD, Gonzalez-Quintana J (Apr 2010). "Coding sequence rare variants identified in MYBPC3, MYH6, TPM1, TNNC1, and TNNI3 from 312 patients with familial or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy". Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 3 (2): 155–161. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.912345. PMC 2908892. PMID 20215591.

- ^ van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, van Tintelen JP, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Werf R, Jongbloed JD, Paulus WJ, Dooijes D, van den Berg MP (May 2010). "Peripartum cardiomyopathy as a part of familial dilated cardiomyopathy". Circulation. 121 (20): 2169–2175. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.929646. PMID 20458010.

- ^ Mogensen J, Murphy RT, Shaw T, Bahl A, Redwood C, Watkins H, Burke M, Elliott PM, McKenna WJ (Nov 2004). "Severe disease expression of cardiac troponin C and T mutations in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 44 (10): 2033–2040. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.027. PMID 15542288.

- ^ Memo M, Leung MC, Ward DG, dos Remedios C, Morimoto S, Zhang L, Ravenscroft G, McNamara E, Nowak KJ, Marston SB, Messer AE (Jul 2013). "Familial dilated cardiomyopathy mutations uncouple troponin I phosphorylation from changes in myofibrillar Ca²⁺ sensitivity". Cardiovascular Research. 99 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvt071. PMID 23539503.

- ^ Hwang PM, Cai F, Pineda-Sanabria SE, Corson DC, Sykes BD (Oct 2014). "The cardiac-specific N-terminal region of troponin I positions the regulatory domain of troponin C". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (40): 14412–14417. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11114412H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1410775111. PMC 4210035. PMID 25246568.

- ^ Russell AJ, Hartman JJ, Hinken AC, Muci AR, Kawas R, Driscoll L, Godinez G, Lee KH, Marquez D, Browne WF, Chen MM, Clarke D, Collibee SE, Garard M, Hansen R, Jia Z, Lu PP, Rodriguez H, Saikali KG, Schaletzky J, Vijayakumar V, Albertus DL, Claflin DR, Morgans DJ, Morgan BP, Malik FI (Mar 2012). "Activation of fast skeletal muscle troponin as a potential therapeutic approach for treating neuromuscular diseases". Nature Medicine. 18 (3): 452–455. doi:10.1038/nm.2618. PMC 3296825. PMID 22344294.

- ^ Shefner JM, Wolff AA, Meng L (Dec 2013). "The relationship between tirasemtiv serum concentration and functional outcomes in patients with ALS". Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis & Frontotemporal Degeneration. 14 (7–8): 582–5. doi:10.3109/21678421.2013.817587. PMID 23952600. S2CID 25563161.

- ^ Bauer TA, Wolff AA, Hirsch AT, Meng LL, Rogers K, Malik FI, Hiatt WR (May 2014). "Effect of tirasemtiv, a selective activator of the fast skeletal muscle troponin complex, in patients with peripheral artery disease". Vascular Medicine. 19 (4): 297–306. doi:10.1177/1358863X14534516. PMID 24872402. S2CID 25185883.

- ^ Sanders DB, Rosenfeld J, Dimachkie MM, Meng L, Malik FI, Andrews J, Barohn R, Corse A, Deboo A, Felice K, Harati Y, Heiman-Patterson T, Howard JF, Jackson C, Juel V, Katz J, Lee J, Massey J, McVey A, Mozaffar T, Pasnoor M, Small G, So Y, Wang AK, Weinberg D, Wolff AA (Apr 2015). "A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy, safety, and tolerability of single doses of tirasemtiv in patients with acetylcholine receptor-binding antibody-positive myasthenia gravis". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (2): 455–60. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0345-y. PMC 4404445. PMID 25742919.

- ^ Sorsa T, Pollesello P, Permi P, Drakenberg T, Kilpeläinen I (Sep 2003). "Interaction of levosimendan with cardiac troponin C in the presence of cardiac troponin I peptides". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 35 (9): 1055–61. doi:10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00178-0. PMID 12967628.

- ^ Robertson IM, Baryshnikova OK, Li MX, Sykes BD (Jul 2008). "Defining the binding site of levosimendan and its analogues in a regulatory cardiac troponin C-troponin I complex". Biochemistry. 47 (28): 7485–95. doi:10.1021/bi800438k. PMC 2652250. PMID 18570382.

- ^ Kleerekoper Q, Putkey JA (Aug 1999). "Drug binding to cardiac troponin C". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (34): 23932–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.34.23932. PMID 10446160.

- ^ Szilágyi S, Pollesello P, Levijoki J, Kaheinen P, Haikala H, Edes I, Papp Z (Feb 2004). "The effects of levosimendan and OR-1896 on isolated hearts, myocyte-sized preparations and phosphodiesterase enzymes of the guinea pig". European Journal of Pharmacology. 486 (1): 67–74. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.12.005. PMID 14751410.

- ^ Ørstavik Ø, Manfra O, Andressen KW, Andersen GØ, Skomedal T, Osnes JB, Levy FO, Krobert KA (2015). "The inotropic effect of the active metabolite of levosimendan, OR-1896, is mediated through inhibition of PDE3 in rat ventricular myocardium". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0115547. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1015547O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115547. PMC 4349697. PMID 25738589.

- ^ Robertson IM, Sun YB, Li MX, Sykes BD (Dec 2010). "A structural and functional perspective into the mechanism of Ca2+-sensitizers that target the cardiac troponin complex". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 49 (6): 1031–41. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.08.019. PMC 2975748. PMID 20801130.

- ^ Lindert S, Li MX, Sykes BD, McCammon JA (Feb 2015). "Computer-aided drug discovery approach finds calcium sensitizer of cardiac troponin". Chemical Biology & Drug Design. 85 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1111/cbdd.12381. PMC 4456024. PMID 24954187.

- ^ Wang X, Li MX, Sykes BD (Aug 2002). "Structure of the regulatory N-domain of human cardiac troponin C in complex with human cardiac troponin I147-163 and bepridil". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (34): 31124–33. doi:10.1074/jbc.M203896200. PMID 12060657.

- ^ Oleszczuk M, Robertson IM, Li MX, Sykes BD (May 2010). "Solution structure of the regulatory domain of human cardiac troponin C in complex with the switch region of cardiac troponin I and W7: the basis of W7 as an inhibitor of cardiac muscle contraction". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 48 (5): 925–33. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.01.016. PMC 2854253. PMID 20116385.

- ^ Wang X, Li MX, Spyracopoulos L, Beier N, Chandra M, Solaro RJ, Sykes BD (Jul 2001). "Structure of the C-domain of human cardiac troponin C in complex with the Ca2+ sensitizing drug EMD 57033". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (27): 25456–66. doi:10.1074/jbc.M102418200. PMID 11320096.

- ^ Pineda-Sanabria SE, Robertson IM, Sykes BD (Mar 2011). "Structure of trans-resveratrol in complex with the cardiac regulatory protein troponin C". Biochemistry. 50 (8): 1309–20. doi:10.1021/bi101985j. PMC 3043152. PMID 21226534.

- ^ Li Y, Love ML, Putkey JA, Cohen C (May 2000). "Bepridil opens the regulatory N-terminal lobe of cardiac troponin C". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (10): 5140–5. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.5140L. doi:10.1073/pnas.090098997. PMC 25795. PMID 10792039.

- ^ Robertson IM, Li MX, Sykes BD (Aug 2009). "Solution structure of human cardiac troponin C in complex with the green tea polyphenol, (-)-epigallocatechin 3-gallate". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (34): 23012–23. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.021352. PMC 2755708. PMID 19542563.

External links

- Mass spectrometry characterization of human TNNC1 at COPaKB Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine.[1]

- GeneReviews/NIH/NCBI/UW entry on Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Overview

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P63316 (Troponin C, slow skeletal and cardiac muscles) at the PDBe-KB.

- ^ Zong NC, Li H, Li H, Lam MP, Jimenez RC, Kim CS, Deng N, Kim AK, Choi JH, Zelaya I, Liem D, Meyer D, Odeberg J, Fang C, Lu HJ, Xu T, Weiss J, Duan H, Uhlen M, Yates JR, Apweiler R, Ge J, Hermjakob H, Ping P (Oct 2013). "Integration of cardiac proteome biology and medicine by a specialized knowledgebase". Circulation Research. 113 (9): 1043–53. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301151. PMC 4076475. PMID 23965338.