Trinucleotide repeat disorder

| Trinucleotide repeat disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Trinucleotide repeat expansion disorders, Triplet repeat expansion disorders or Codon reiteration disorders | |

Trinucleotide repeat disorders, also known as microsatellite expansion diseases, are a set of over 50 genetic disorders caused by trinucleotide repeat expansion, a kind of mutation in which repeats of three nucleotides (trinucleotide repeats) increase in copy numbers until they cross a threshold above which they become unstable.[1] Depending on its location, the unstable trinucleotide repeat may cause defects in a protein encoded by a gene; change the regulation of gene expression; produce a toxic RNA, or lead to chromosome instability. In general, the larger the expansion the faster the onset of disease, and the more severe the disease becomes.[1]Trinucleotide repeats are a subset of a larger class of unstable microsatellite repeats that occur throughout all genomes.

The first trinucleotide repeat disease to be identified was fragile X syndrome, which has since been mapped to the long arm of the X chromosome. Patients carry from 230 to 4000 CGG repeats in the gene that causes fragile X syndrome, while unaffected individuals have up to 50 repeats and carriers of the disease have 60 to 230 repeats. The chromosomal instability resulting from this trinucleotide expansion presents clinically as intellectual disability, distinctive facial features, and macroorchidism in males. The second DNA-triplet repeat disease, fragile X-E syndrome, was also identified on the X chromosome, but was found to be the result of an expanded CCG repeat.[2] The discovery that trinucleotide repeats could expand during intergenerational transmission and could cause disease was the first evidence that not all disease-causing mutations are stably transmitted from parent to offspring.[1]

There are several known categories of trinucleotide repeat disorder. Category I includes Huntington's disease (HD) and the spinocerebellar ataxias. These are caused by a CAG repeat expansion in protein-coding portions, or exons, of specific genes. Category II expansions are also found in exons, and tend to be more phenotypically diverse with heterogeneous expansions that are generally small in magnitude. Category III includes fragile X syndrome, myotonic dystrophy, two of the spinocerebellar ataxias, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, and Friedreich's ataxia. These diseases are characterized by typically much larger repeat expansions than the first two groups, and the repeats are located in introns rather than exons.[citation needed]

Types

Some of the problems in trinucleotide repeat syndromes result from causing alterations in the coding region of the gene, while others are caused by altered gene regulation.[1] In over half of these disorders, the repeated trinucleotide, or codon, is CAG. In a coding region, CAG codes for glutamine (Q), so CAG repeats result in an expanded polyglutamine tract.[3] These diseases are commonly referred to as polyglutamine (or polyQ) diseases. The repeated codons in the remaining disorders do not code for glutamine, and these can be classified as non-polyQ or non-coding trinucleotide repeat disorders.

Polyglutamine (PolyQ) diseases

| Type | Gene | Normal PolyQ repeats | Pathogenic PolyQ repeats |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRPLA (Dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy) | ATN1 or DRPLA | 6 - 35 | 49 - 88 |

| HD (Huntington's disease) | HTT | 6 - 35 | 36 - 250 |

| SBMA (Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy)[4] | AR | 4 - 34 | 35 - 72 |

| SCA1 (Spinocerebellar ataxia Type 1) | ATXN1 | 6 - 35 | 49 - 88 |

| SCA2 (Spinocerebellar ataxia Type 2) | ATXN2 | 14 - 32 | 33 - 77 |

| SCA3 (Spinocerebellar ataxia Type 3 or Machado-Joseph disease) | ATXN3 | 12 - 40 | 55 - 86 |

| SCA6 (Spinocerebellar ataxia Type 6) | CACNA1A | 4 - 18 | 21 - 30 |

| SCA7 (Spinocerebellar ataxia Type 7) | ATXN7 | 7 - 17 | 38 - 120 |

| SCA17 (Spinocerebellar ataxia Type 17) | TBP | 25 - 42 | 47 - 63 |

Non-coding trinucleotide repeat disorders

| Type | Gene | Codon | Normal | Pathogenic | Mechanism[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRAXA (Fragile X syndrome) | FMR1 | CGG (5' UTR) | 6 - 53 | 230+ | abnormal methylation |

| FXTAS (Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome) | FMR1 | CGG (5' UTR) | 6 - 53 | 55-200 | increased expression, and a novel polyglycine product[5] |

| FRAXE (Fragile XE mental retardation) | AFF2 | CCG (5' UTR) | 6 - 35 | 200+ | abnormal methylation |

| Baratela-Scott syndrome[6] | XYLT1 | GGC (5' UTR) | 6 - 35 | 200+ | abnormal methylation |

| FRDA (Friedreich's ataxia) | FXN | GAA (Intron) | 7 - 34 | 100+ | impaired transcription |

| DM1 (Myotonic dystrophy Type 1) | DMPK | CTG (3' UTR) | 5 - 34 | 50+ | RNA-based; unbalanced DMPK/ZNF9 expression levels |

| SCA8 (Spinocerebellar ataxia Type 8) | SCA8 | CTG (RNA) | 16 - 37 | 110 - 250 | ? RNA |

| SCA12 (Spinocerebellar ataxia Type 12)[7][8] | PPP2R2B | CAG (5' UTR) | 7 - 28 | 55 - 78 | effect on promoter function |

Symptoms and signs

As of 2017[update], ten neurological and neuromuscular disorders were known to be caused by an increased number of CAG repeats.[9] Although these diseases share the same repeated codon (CAG) and some symptoms, the repeats are found in different, unrelated genes. Except for the CAG repeat expansion in the 5' UTR of PPP2R2B in SCA12, the expanded CAG repeats are translated into an uninterrupted sequence of glutamine residues, forming a polyQ tract, and the accumulation of polyQ proteins damages key cellular functions such as the ubiquitin-proteasome system. A common symptom of polyQ diseases is the progressive degeneration of nerve cells, usually affecting people later in life. However different polyQ-containing proteins damage different subsets of neurons, leading to different symptoms.[10]

The non-polyQ diseases or non-coding trinucleotide repeat disorders do not share any specific symptoms and are unlike the PolyQ diseases. In some of these diseases, such as Fragile X syndrome, the pathology is caused by lack of the normal function of the protein encoded by the affected gene. In others, such as Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1, the pathology is caused by a change in protein expression or function mediated through changes in the messenger RNA produced by the expression of the affected gene.[1] In yet others, the pathology is caused by toxic assemblies of RNA in the nuclei of cells.[11]

Genetics

| Repeat count | Classification | Disease status |

|---|---|---|

| <28 | Normal | Unaffected |

| 28–35 | Intermediate | Unaffected |

| 36–40 | Reduced-penetrance | May be affected |

| >40 | Full-penetrance | Affected |

Trinucleotide repeat disorders generally show genetic anticipation: their severity increases with each successive generation that inherits them. This is likely explained by the addition of CAG repeats in the affected gene as the gene is transmitted from parent to child. For example, Huntington's disease occurs when there are more than 35 CAG repeats on the gene coding for the protein HTT. A parent with 35 repeats would be considered normal and would not exhibit any symptoms of the disease.[12] However, that parent's offspring would be at an increased risk of developing Huntington's compared to the general population, as it would take only the addition of one more CAG codon to cause the production of mHTT (mutant HTT), the protein responsible for disease.

Huntington's very rarely occurs spontaneously; it is almost always the result of inheriting the defective gene from an affected parent. However, sporadic cases of Huntington's in individuals who have no history of the disease in their families do occur. Among these sporadic cases, there is a higher frequency of individuals with a parent who already has a significant number of CAG repeats in their HTT gene, especially those whose repeats approach the number (36) required for the disease to manifest. Each successive generation in a Huntington's-affected family may add additional CAG repeats, and the higher the number of repeats, the more severe the disease and the earlier its onset.[12] As a result, families that have had Huntington's for many generations show an earlier age of disease onset and faster disease progression.[12]

Non-trinucleotide expansions

The majority of diseases caused by expansions of simple DNA repeats involve trinucleotide repeats, but tetra-, penta- and dodecanucleotide repeat expansions are also known that cause disease. For any specific hereditary disorder, only one repeat expands in a particular gene.[13]

Mechanism

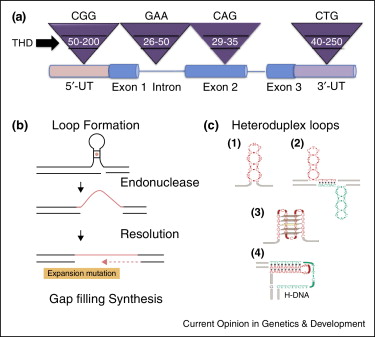

Triplet expansion is caused by slippage during DNA replication or during DNA repair synthesis.[15] Because the tandem repeats have identical sequence to one another, base pairing between two DNA strands can take place at multiple points along the sequence. This may lead to the formation of 'loop out' structures during DNA replication or DNA repair synthesis.[16] This may lead to repeated copying of the repeated sequence, expanding the number of repeats. Additional mechanisms involving hybrid RNA:DNA intermediates have been proposed.[17][18]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Trinucleotide repeat disorder is done via clinical features, family history and PCR[19]

Treatment

The management of this disorder depends on the presenting features, hence Coenzyme Q, High dose ascorbic acid, Idebenone, and N-acetylcysteine, are used in the case of Friedrich's ataxia.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Orr HT, Zoghbi HY (2007). "Trinucleotide repeat disorders". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 30 (1): 575–621. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113042. PMID 17417937.

- ↑ "Fragile XE syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ↑ Adegbuyiro A, Sedighi F, Pilkington AW, Groover S, Legleiter J (March 2017). "Proteins Containing Expanded Polyglutamine Tracts and Neurodegenerative Disease". Biochemistry. 56 (9): 1199–1217. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00936. PMC 5727916. PMID 28170216.

- ↑ Laskaratos A, Breza M, Karadima G, Koutsis G (June 2021). "Wide range of reduced penetrance alleles in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy: a model-based approach". Journal of Medical Genetics. 58 (6): 385–391. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-106963. PMID 32571900. S2CID 219991108.

- ↑ Gao FB, Richter JD (January 2017). "Microsatellite Expansion Diseases: Repeat Toxicity Found in Translation". Neuron. 93 (2): 249–251. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2017.01.001. PMID 28103472.

- ↑ LaCroix AJ, Stabley D, Sahraoui R, Adam MP, Mehaffey M, Kernan K, et al. (January 2019). "GGC Repeat Expansion and Exon 1 Methylation of XYLT1 Is a Common Pathogenic Variant in Baratela-Scott Syndrome". American Journal of Human Genetics. 104 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.11.005. PMC 6323552. PMID 30554721.

- ↑ Srivastava AK, Takkar A, Garg A, Faruq M (January 2017). "Clinical behaviour of spinocerebellar ataxia type 12 and intermediate length abnormal CAG repeats in PPP2R2B". Brain. 140 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1093/brain/aww269. PMID 27864267.

- ↑ O'Hearn E, Holmes SE, Margolis RL (2012-01-01). "Chapter 34 - Spinocerebellar ataxia type 12". In Subramony SH, Dürr A (eds.). Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Ataxic Disorders. Vol. 103. Elsevier. pp. 535–547. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-51892-7.00034-6. ISBN 9780444518927. PMID 21827912. S2CID 25745894. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ↑ Adegbuyiro A, Sedighi F, Pilkington AW, Groover S, Legleiter J (March 2017). "Proteins Containing Expanded Polyglutamine Tracts and Neurodegenerative Disease". Biochemistry. 56 (9): 1199–1217. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00936. PMC 5727916. PMID 28170216.

- ↑ Fan HC, Ho LI, Chi CS, Chen SJ, Peng GS, Chan TM, et al. (May 2014). "Polyglutamine (PolyQ) diseases: genetics to treatments". Cell Transplantation. 23 (4–5): 441–458. doi:10.3727/096368914X678454. PMID 24816443.

- ↑ Sanders DW, Brangwynne CP (June 2017). "Neurodegenerative disease: RNA repeats put a freeze on cells". Nature. 546 (7657): 215–216. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..215S. doi:10.1038/nature22503. PMID 28562583.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Walker FO (January 2007). "Huntington's disease". Lancet. 369 (9557): 218–228. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1. PMID 17240289. S2CID 46151626.

- ↑ Mirkin SM (June 2007). "Expandable DNA repeats and human disease". Nature. 447 (7147): 932–940. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..932M. doi:10.1038/nature05977. PMID 17581576. S2CID 4397592.

- ↑ Lee, Do-Yup; McMurray, Cynthia T. (1 June 2014). "Trinucleotide expansion in disease: why is there a length threshold?". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 26: 131–140. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2014.07.003. ISSN 0959-437X. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ↑ Usdin K, House NC, Freudenreich CH (2015). "Repeat instability during DNA repair: Insights from model systems". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 50 (2): 142–167. doi:10.3109/10409238.2014.999192. PMC 4454471. PMID 25608779.

- ↑ Petruska J, Hartenstine MJ, Goodman MF (February 1998). "Analysis of strand slippage in DNA polymerase expansions of CAG/CTG triplet repeats associated with neurodegenerative disease". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (9): 5204–5210. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.9.5204. PMID 9478975.

- ↑ McIvor EI, Polak U, Napierala M (2010). "New insights into repeat instability: role of RNA•DNA hybrids". RNA Biology. 7 (5): 551–558. doi:10.4161/rna.7.5.12745. PMC 3073251. PMID 20729633.

- ↑ Salinas-Rios V, Belotserkovskii BP, Hanawalt PC (September 2011). "DNA slip-outs cause RNA polymerase II arrest in vitro: potential implications for genetic instability". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (17): 7444–7454. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr429. PMC 3177194. PMID 21666257.review

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Ramakrishnan, Sharanya; Gupta, Vikas (2022). "Trinucleotide Repeat Disorders". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2023-03-18. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

External links

- Trinucleotide+Repeat+Expansion at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on DRPLA Archived 2010-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Archived 2016-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Genetics Home Reference Archived 2019-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Pages with script errors

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2011

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2017

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Genetic disorders by mechanism

- Huntington's disease

- Trinucleotide repeat disorders