Tricuspid insufficiency

| Tricuspid insufficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Tricuspid regurgitation | |

| |

| Diagram of the heart with a black arrow showing the location and direction of the abnormal blood flow | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | Few symptoms initially, may develop peripheral swelling, liver enlargement, ascites[1] |

| Complications | Heart failure, atrial fibrillation[1] |

| Causes | Pulmonary hypertension, infective endocarditis, hyperthyroidism, Ebstein anomaly, rheumatic heart disease, carcinoid syndrome, connective tissue disorder, lupus, pulmonary valve stenosis, certain medications such as fenfluramine[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Suspected based on a systolic murmur, confirmed by echocardiogram[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Mitral regurgitation |

| Treatment | Furosemide, surgery[1] |

| Prognosis | Generally good[1] |

| Frequency | Relatively common[1] |

Tricuspid insufficiency (TI), also known as tricuspid regurgitation (TR), is a type of valvular heart disease in which there is backward flow of blood from the right ventricle, through the tricuspid valve, into the right atrium, when the heart contracts.[1] Early on few symptoms may be present.[1] Later on heart failure may develop with peripheral swelling, liver enlargement, and ascites.[1] Other complications may include atrial fibrillation.[1]

Causes include dilation of the right ventricle, such as from pulmonary hypertension, cor pulmonale, or after a heart attack.[2] Other causes include infective endocarditis, hyperthyroidism, Ebstein anomaly, rheumatic heart disease, carcinoid syndrome, connective tissue disorder, lupus, pulmonary valve stenosis, and certain medications such as fenfluramine.[1] The diagnosis may be suspected based on a systolic murmur and confirmed by an ultrasound of the heart.[1]

Treatment depends on the underlying cause and the severity.[1] In those with left-sided heart failure furosemide and salt restriction may be recommended.[1] Tricuspid valve surgery may be recommended in those with severe disease with significant symptoms or when repairing other valves.[1] In cases were the valve is infected it may be removed without immediate replacement.[1] Outcomes are generally good.[1]

Triscuspid insufficiency is relatively common.[1] The percentage of people newly affected per year is about 0.9% in the United States.[1] Males and females are affected equally frequently.[1] Surgery to replace the tricuspid valve was first described in 1963.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms depend on the severity. Severe TR causes right-sided heart failure, with the development of ascites and peripheral edema.[4]

A pansystolic heart murmur may be heard on auscultation of the chest.[2] The murmur is usually of low frequency and best heard on the lower left sternal border. It increases with inspiration, and decreases with expiration: this is known as Carvallo's sign. However, the murmur may be inaudible due to the relatively low pressures in the right side of the heart. A third heart sound may also be present, also heard at the lower sternal border, and increasing in intensity with inspiration.[5][6]

On examination of the neck, there may be giant C-V waves in the jugular pulse.[7] With severe TR, there may be an enlarged liver detected on palpation of the right upper quadrant of the abdomen; the liver may be pulsatile on palpation and even on inspection.[2]

Causes

The causes of TR may be classified as congenital[8] or acquired; another classification divides the causes into primary or secondary. Congenital abnormalities are much less common than acquired. The most common acquired TR is due to right ventricular dilatation. Such dilatation is most often due left heart failure or pulmonary hypertension. Other causes of right ventricular dilatation include right ventricular infarction, inferior myocardial infarction, and cor pulmonale.[medical citation needed]

In regards to primary and secondary causes they are:[9]

- Primary causes

- Rheumatic

- Myxomatous

- Ebstein anomaly

- Endomyocardial fibrosis

- Endocarditis

- Traumatic (blunt chest injury)

- Secondary causes

- Left ventricular systolic dysfunction

- Mitral valve stenosis or regurgitation

- Chronic lung disease

- Pulmonary thromboembolism

- Myocardial disease

- Right ventricular ischemia and infraction

- Left to right shunt

- Carcinoid heart disease

Mechanism

In terms of the mechanism of tricuspid insufficiency it involves the expansion of the tricuspid annulus (fibrous rings of heart). Tricuspid insufficiency is linked to geometric changes of the tricuspid annulus (decreased tricuspid annular release). The leaflets shape are normal but prevented from normal working mechanism due to a distortion of spatial relationships of leaflets and chords.[10] It is also contemplated that the process via which tricuspid regurgitation emerges, is a decrease of contraction of the myocardium around the annulus,[11]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of TR may be suspected if the typical murmur of TR is heard. Severe TR may be suspected if right ventricular enlargement is seen on chest x-ray, and other causes of this enlargement are ruled out.

Definitive diagnosis is made by echocardiogram, which is capable of measuring both the presence and the severity of the TR, as well as right ventricular dimensions and systolic pressures.[12]

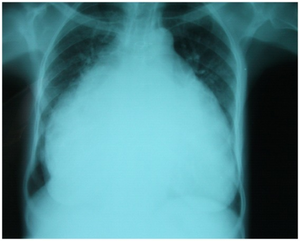

-

Chest-Xray: enlarged heart in TR and mitral valve disease

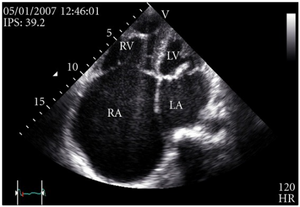

-

Transthoracic echo: enlargement of the right atrium in TR and mitral valve disease

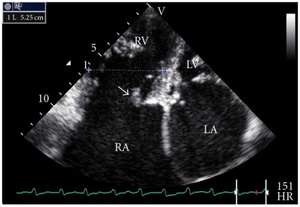

-

Transthoracic echo: TR (arrow)

-

Echocardiogram: severe TR

Management

Medical

Generally, medical rather than surgical treatment of TR is recommended if the cause is right ventricular dilatation or left-sided heart failure.[13]

Surgery

Tricuspid valve replacement using either a mechanical prosthesis or a bioprosthesis may be indicated. (Mechanical prostheses may cause thrombo‐embolic phenomena, bioprostheses may have a degeneration problem).[11] Some evidence suggests that there are no significant differences between a mechanical or biological tricuspid valve in a recipient.[14]

Surgery vs. no surgery for TR has been statistically assessed by looking back on consecutive series of hospital cases, mainly of secondary causes. In these cases, one finds that surgery predicts outliving non-surgery cases initially matched in health ~60% of the time (HR = .74).[15]

Prognosis

The prognosis of TR is less favorable for males than females. Survival rates are proportional to TR severity;[16] but even mild TR reduces survival compared to those with no TR. If the TR is due to left heart failure or pulmonary hypertension, prognosis is usually dictated by these conditions, not the TR.[medical citation needed]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 Mulla, S; Asuka, E; Siddiqui, WJ (January 2020). "Tricuspid Regurgitation". PMID 30252377.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Bunce, Nicholas H.; Ray, Robin; Patel, Hitesh (2020). "30. Cardiology". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 1101. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2022-02-11. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ↑ Jonas, Richard (2002). Comprehensive Surgical Management of Congenital Heart Disease. CRC Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-4441-1412-6. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2020-12-22.

- ↑ Tricuspid Regurgitation~clinical at eMedicine

- ↑ "Tricuspid Valve Disease & Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) | Patient". Patient. Archived from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- ↑ Berg, Dale; Worzala, Katherine (2006-01-01). Atlas of Adult Physical Diagnosis. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 90. ISBN 9780781741903. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- ↑ Rehman, Habib Ur (2013). "Giant C-V Waves of Tricuspid Regurgitation". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (20): e27. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1103312. PMID 24224640.

- ↑ Said, Sameh M; Dearani, Joseph A; Burkhart, Harold M; Connolly, Heidi M; Eidem, Ben; Stensrud, Paul E; Schaff, Hartzell V (2014). "Management of tricuspid regurgitation in congenital heart disease: Is survival better with valve repair?". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 147 (1): 412–419. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.08.034. PMID 24084288.

- ↑ Rogers, J. H; Bolling, S. F (2009). "The Tricuspid Valve: Current Perspective and Evolving Management of Tricuspid Regurgitation". Circulation. 119 (20): 2718–2725. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842773. PMID 19470900.

- ↑ Hung, Judy (2010). "The Pathogenesis of Functional Tricuspid Regurgitation". Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 22 (1): 76–78. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2010.05.004. PMID 20813321.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Antunes, M. J; Barlow, J. B (2005). "Management of tricuspid valve regurgitation". Heart. 93 (2): 271–276. doi:10.1136/hrt.2006.095281. PMC 1861404. PMID 17228081.

- ↑ Shah PM, Raney AA; Tricuspid valve disease. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2008 Feb33(2):47-84

- ↑ Tricuspid Regurgitation~treatment at eMedicine

- ↑ "BestBets: Should the tricuspid valve be replaced with a mechanical or biological valve?". www.bestbets.org. Archived from the original on 2018-08-14. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- ↑ Kelly, Brian J.; Ho Luxford, Jamahal Maeng; Butler, Carolyn Goldberg; Huang, Chuan-Chin; Wilusz, Kerry; Ejiofor, Julius I.; Rawn, James D.; Fox, John A.; Shernan, Stanton K.; Muehlschlegel, Jochen Daniel (2018). "Severity of tricuspid regurgitation is associated with long-term mortality". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 155 (3): 1032–1038.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.09.141. ISSN 1097-685X. PMC 5819734. PMID 29246545. – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

- ↑ Nath, Jayant; Foster, Elyse; Heidenreich, Paul A (2004). "Impact of tricuspid regurgitation on long-term survival". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 43 (3): 405–409. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.036. PMID 15013122.

Further reading

- Haddad, F; Doyle, R; Murphy, D. J; Hunt, S. A (2008). "Right Ventricular Function in Cardiovascular Disease, Part II: Pathophysiology, Clinical Importance, and Management of Right Ventricular Failure". Circulation. 117 (13): 1717–1731. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.653584. PMID 18378625.

- Desai, Ravi R; Vargas Abello, Lina Maria; Klein, Allan L; Marwick, Thomas H; Krasuski, Richard A; Ye, Ying; Nowicki, Edward R; Rajeswaran, Jeevanantham; Blackstone, Eugene H; Pettersson, Gösta B (2013). "Tricuspid regurgitation and right ventricular function after mitral valve surgery with or without concomitant tricuspid valve procedure". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 146 (5): 1126–1132.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.08.061. PMC 4215162. PMID 23010580.

- Badano, Luigi P; Muraru, Denisa; Enriquez-Sarano, Maurice (2013). "Assessment of functional tricuspid regurgitation". European Heart Journal. 34 (25): 1875–1885. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs474. PMID 23303656.

- al.], Hugh D. Allen ... [et; Shaddy, Robert E.; Feltes, Timothy F. (2013). Moss and Adams heart disease in infants, children, and adolescents : including the fetus and young adult (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781451118933. Archived from the original on 2020-07-24. Retrieved 2020-07-22.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- Pages containing links to subscription-or-libraries content

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2015

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2016

- Chronic rheumatic heart diseases

- Valvular heart disease

- RTT