Transient synovitis

| Transient synovitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Toxic synovitis, transitory coxitis, coxitis fugax, acute transient epiphysitis, coxitis serosa seu simplex, phantom hip disease, observation hip[1] | |

| |

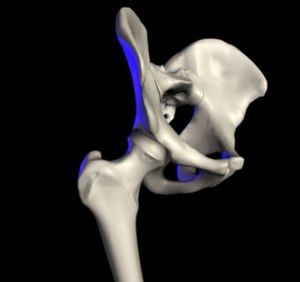

| The hip joint is formed between the femur and acetabulum of the pelvis. | |

| Symptoms | Groin pain, limp[2] |

| Usual onset | 3 to 10 years[3] |

| Duration | < 5 days[3] |

| Causes | Unknown[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Ruling out other potential causes[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Bone fracture, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, discitis, leukemia, septic joint, Lyme disease[3] |

| Treatment | NSAIDs, limited weight-bearing[3] |

| Frequency | Up to 3%[3] |

Transient synovitis of hip, also called toxic synovitis, is a self-limiting inflammation of the lining of the hip joint.[2][4] Symptoms often include pain in the groin, a limp, or refusal to walk.[2][5] Symptoms often come on over a few days and there is generally no fever.[2] Pain generally only occurs with significant movements at the hip.[2] The child generally looks otherwise well.[2]

The exact cause is unknown.[3] A recent viral infection (most commonly an upper respiratory tract infection) or recent injury has been proposed as triggers.[2][4] Diagnosis involves ruling out other potential causes.[3] Blood tests may show mild inflammation.[3] An ultrasound scan may show a fluid collection in the hip joint which may require aspiration to rule out a infection.[3]

Treatment is with NSAIDs and limited weight-bearing.[3] The condition is usually better within two days and clears completely within 2 weeks.[4] The recurrence rate is as high as 25%.[4]

Transient synovitis affects up to 3% of children at some point in time.[3] Most commonly it occurs between three and ten years of age and is the most common cause of hip pain in this age group.[3][6] Rarely other age groups are affected.[4] Boys are affected twice as often as girls.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Transient synovitis causes pain in the hip, thigh, groin or knee on the affected side.[7] There may be a limp (or abnormal crawling in infants) with or without pain. In small infants, the presenting complaint can be unexplained crying (for example, when changing a diaper). The condition is nearly always limited to one side.[7] The pain and limp can range from mild to severe.

Some children may have a slightly raised temperature; high fever and general malaise point to other, more serious conditions. On clinical examination, the child typically holds the hip slightly bent, turned outwards and away from the middle line (flexion, external rotation and abduction).[8] Active and passive movements may be limited because of pain, especially abduction and internal rotation. The hip can be tender to palpation. The log roll test involves gently rotating the entire lower limb inwards and outwards with the patient on his back, to check when muscle guarding occurs. The unaffected hip and the knees, ankles, feet and spine are found to be normal.[9]

Complications

In the past, there have been speculations about possible complications after transient synovitis. The current consensus however is that there is no proof of an increased risk of complications after transient synovitis.[10]

One such previously suspected complication was coxa magna, which is an overgrowth of the femoral head and broadening of the femoral neck, accompanied by changes in the acetabulum, which may lead to subluxation of the femur.[9][11] There was also some controversy about whether continuous high intra-articular pressure in transient synovitis could cause avascular necrosis of the femoral head (Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease), but further studies did not confirm any link between the two conditions.[12]

Diagnosis

There are no set standards for the diagnosis of suspected transient synovitis, so the amount of investigations will depend on the need to exclude other, more serious diseases.

Inflammatory parameters in the blood may be slightly raised (these include erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and white blood cell count), but raised inflammatory markers are strong predictors of other more serious conditions such as septic arthritis.[13][14]

X-ray imaging of the hip is most often unremarkable. Subtle radiographic signs include an accentuated pericapsular shadow, widening of the medial joint space, lateral displacement of the femoral epiphyses with surface flattening (Waldenström sign), prominent obturator shadow, diminution of soft tissue planes around the hip joint or slight demineralisation of the proximal femur. The main reason for radiographic examination is to exclude bony lesions such as occult fractures, slipped upper femoral epiphysis or bone tumours (such as osteoid osteoma). An anteroposterior and frog lateral (Lauenstein) view of the pelvis and both hips is advisable.[15]

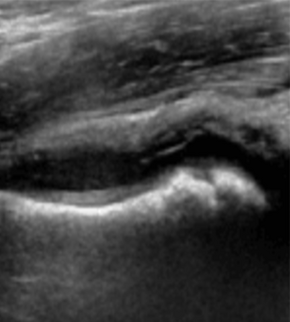

An ultrasound scan of the hip can easily demonstrate fluid inside the joint capsule (Fabella sign), although this is not always present in transient synovitis.[8][16] However, it cannot reliably distinguish between septic arthritis and transient synovitis.[17][18] If septic arthritis needs to be ruled out, needle aspiration of the fluid can be performed under ultrasound guidance.[19] In transient synovitis, the joint fluid will be clear.[7] In septic arthritis, there will be pus in the joint, which can be sent for bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity testing.

More advanced imaging techniques can be used if the clinical picture is unclear; the exact role of different imaging modalities remains uncertain. Some studies have demonstrated findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan) that can differentiate between septic arthritis and transient synovitis (for example, signal intensity of adjacent bone marrow).[20][21][22] Skeletal scintigraphy can be entirely normal in transient synovitis, and scintigraphic findings do not distinguish transient synovitis from other joint conditions in children.[23] CT scanning does not appear helpful.

Differential diagnosis

The term "irritable hip" refers to hip pain of sudden onset, joint stiffness, and limping, and is indicative of an underlying condition such as transient synovitis or infections (like septic arthritis or osteomyelitis).[24] Often the term irritable hip is used as a synonym for transient synovitis.

Pain in or around the hip or limp in children can be due to a large number of conditions. Septic arthritis (a bacterial infection of the joint) is the most important differential diagnosis, because it can quickly cause irreversible damage to the hip joint.[6] Fever, raised inflammatory markers on blood tests and severe symptoms (inability to bear weight, pronounced muscle guarding) all point to septic arthritis,[13][14] but a high index of suspicion remains necessary even if these are not present.[7] Osteomyelitis (infection of the bone tissue) can also cause pain and limp.

Bone fractures, such as a toddler's fracture (spiral fracture of the shin bone), can also cause pain and limp, but are uncommon around the hip joint. Soft tissue injuries can be evident when bruises are present. Muscle or ligament injuries can be contracted during heavy physical activity —however, it is important not to miss a slipped upper femoral epiphysis. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head (Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease) typically occurs in children aged 4–8, and is also more common in boys. There may be an effusion on ultrasound, similar to transient synovitis.[25]

Neurological conditions can also present with a limp. If developmental dysplasia of the hip is missed early in life, it can come to attention later in this way. Pain in the groin can also be caused by diseases of the organs in the abdomen (such as a psoas abscess) or by testicular disease. Rarely, there is an underlying rheumatic condition (juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Lyme arthritis, gonococcal arthritis, ...) or bone tumour.

Treatment

Treatment consists of rest, non-weightbearing and pain medication when needed. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug such as ibuprofen can shorten the disease course (from 4.5 to 2 days) and provide pain control with minimal side effects.[26] If fever occurs or the symptoms persist, other diagnoses need to be considered.[9]

References

- ↑ Do TT (Feb 2000). "Transient synovitis as a cause of painful limps in children". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 12 (1): 48–51. doi:10.1097/00008480-200002000-00010. PMID 10676774.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Cook, PC (December 2014). "Transient synovitis, septic hip, and Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease: an approach to the correct diagnosis". Pediatric clinics of North America. 61 (6): 1109–18. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2014.08.002. PMID 25439014.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Ryan, DD (1 June 2016). "Differentiating Transient Synovitis of the Hip from More Urgent Conditions". Pediatric annals. 45 (6): e209-13. doi:10.3928/00904481-20160427-01. PMID 27294495.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Whitelaw, CC; Varacallo, M (January 2020). "Transient Synovitis". PMID 29083677.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Nouri, A; Walmsley, D; Pruszczynski, B; Synder, M (January 2014). "Transient synovitis of the hip: a comprehensive review". Journal of pediatric orthopedics. Part B. 23 (1): 32–6. doi:10.1097/BPB.0b013e328363b5a3. PMID 23812087.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hart JJ (Oct 1996). "Transient synovitis of the hip in children". Am Fam Physician. 54 (5): 1587–91, 1595–6. PMID 8857781.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Scott Moses, MD. "Transient hip tenosynovitis Archived 2007-09-16 at the Wayback Machine". Family practice notebook. Revision of August 9, 2007. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Irritable hip Archived 2016-08-07 at the Wayback Machine. General Practice Notebook. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 ped/1676 at eMedicine

- ↑ Mattick A, Turner A, Ferguson J, Beattie T, Sharp J (Sep 1999). "Seven year follow up of children presenting to the accident and emergency department with irritable hip". J Accid Emerg Med. 16 (5): 345–7. doi:10.1136/emj.16.5.345. PMC 1347055. PMID 10505915.

- ↑ Sharwood PF (Dec 1981). "The irritable hip syndrome in children. A long-term follow-up". Acta Orthop Scand. 52 (6): 633–8. doi:10.3109/17453678108992159. PMID 7331801.

- ↑ Kallio P, Ryöppy S, Kunnamo I (Nov 1986). "Transient synovitis and Perthes' disease. Is there an aetiological connection?". J Bone Joint Surg Br. 68 (5): 808–11. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.68B5.3782251. PMID 3782251. Archived from the original on 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Caird MS, Flynn JM, Leung YL, Millman JE, D'Italia JG, Dormans JP (Jun 2006). "Factors distinguishing septic arthritis from transient synovitis of the hip in children. A prospective study". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 88 (6): 1251–7. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00216. PMID 16757758. S2CID 29137759.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kocher MS, Mandiga R, Zurakowski D, Barnewolt C, Kasser JR (Aug 2004). "Validation of a clinical prediction rule for the differentiation between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 86-A (8): 1629–35. doi:10.2106/00004623-200408000-00005. PMID 15292409. S2CID 13529642. Archived from the original on 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ Gough-Palmer A, McHugh K (Jun 2007). "Investigating hip pain in a well child". BMJ. 334 (7605): 1216–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.39188.515741.47. PMC 1892599. PMID 17556478.

- ↑ Nicola Wright, Vince Choudhery. Ultrasound is better than x-ray at detecting hip effusions in the limping child Archived 2008-04-04 at the Wayback Machine. BestBETs.org . Retrieved December 22, 2007

- ↑ Zamzam MM (Nov 2006). "The role of ultrasound in differentiating septic arthritis from transient synovitis of the hip in children". J Pediatr Orthop B. 15 (6): 418–22. doi:10.1097/01.bpb.0000228388.32184.7f. PMID 17001248. S2CID 27006647.

- ↑ Bienvenu-Perrard M, de Suremain N, Wicart P, et al. (Mar 2007). "[Benefit of hip ultrasound in management of the limping child]" [Benefit of hip ultrasound in management of the limping child]. J Radiol (in French). 88 (3 Pt 1): 377–83. doi:10.1016/S0221-0363(07)89834-9. PMID 17457269. Archived from the original on 2020-05-11. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Skinner J, Glancy S, Beattie TF, Hendry GM (Mar 2002). "Transient synovitis: is there a need to aspirate hip joint effusions?". Eur J Emerg Med. 9 (1): 15–8. doi:10.1097/00063110-200203000-00005. PMID 11989490. S2CID 29742427.

- ↑ Kwack KS, Cho JH, Lee JH, Cho JH, Oh KK, Kim SY (Aug 2007). "Septic arthritis versus transient synovitis of the hip: gadolinium-enhanced MRI finding of decreased perfusion at the femoral epiphysis". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 189 (2): 437–45. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.2080. PMID 17646472. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- ↑ Yang WJ, Im SA, Lim GY, et al. (Nov 2006). "MR imaging of transient synovitis: differentiation from septic arthritis". Pediatr Radiol. 36 (11): 1154–8. doi:10.1007/s00247-006-0289-9. PMID 17019590. S2CID 23475331.

- ↑ Lee SK, Suh KJ, Kim YW, et al. (May 1999). "Septic arthritis versus transient synovitis at MR imaging: preliminary assessment with signal intensity alterations in bone marrow". Radiology. 211 (2): 459–65. doi:10.1148/radiology.211.2.r99ma47459. PMID 10228529.

- ↑ Connolly LP, Treves ST (Jun 1998). "Assessing the limping child with skeletal scintigraphy". J Nucl Med. 39 (6): 1056–61. PMID 9627343. Archived from the original on 2020-03-15. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ Fischer SU, Beattie TF (Nov 1999). "The limping child: epidemiology, assessment and outcome". J Bone Joint Surg Br. 81 (6): 1029–34. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.81B6.9607. PMID 10615981. Archived from the original on 2020-03-15. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease at eMedicine

- ↑ Kermond S, Fink M, Graham K, Carlin JB, Barnett P (Sep 2002). "A randomized clinical trial: should the child with transient synovitis of the hip be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs?". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 40 (3): 294–9. doi:10.1067/mem.2002.126171. PMID 12192353.

Further reading

- Leet AI, Skaggs DL (Feb 2000). "Evaluation of the acutely limping child". Am Fam Physician. 61 (4): 1011–8. PMID 10706154. Archived from the original on 2008-05-14. Retrieved 2007-12-22.: An illustrated, free full-text review with emphasis on clinical examination of the acutely limping child.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |