Tolosa–Hunt syndrome

| Tolosa–Hunt syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Painful ophthalmoplegia | |

| |

| Neuro-ophthalmologic examination showing ophthalmoplegia in a patient with Tolosa–Hunt syndrome, prior to treatment. The central image represents forward gaze, and each image around it represents gaze in that direction (for example, in the upper left image, the patient looks up and right; the left eye is unable to accomplish this movement). The examination shows ptosis of the left eyelid, exotropia (outward deviation) of the primary gaze of the left eye, and paresis (weakness) of the left third, fourth and sixth cranial nerves. | |

Tolosa–Hunt syndrome is a rare disorder characterized by severe and unilateral headaches with orbital pain, along with weakness and paralysis (ophthalmoplegia) of certain eye muscles (extraocular palsies).[1]

In 2004, the International Headache Society provided a definition of the diagnostic criteria which included granuloma.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms are usually limited to one side of the head, and in most cases the individual affected will experience intense, sharp pain and paralysis of muscles around the eye.[3] Symptoms may subside without medical intervention, yet recur without a noticeable pattern.[4]

In addition, affected individuals may experience paralysis of various facial nerves and drooping of the upper eyelid (ptosis). Other signs include double vision, fever, chronic fatigue, vertigo or arthralgia. Occasionally the patient may present with a feeling of protrusion of one or both eyeballs (exophthalmos).[3][4]

Causes

The cause of Tolosa–Hunt syndrome is not known, but the disorder is thought to be, and often assumed to be, associated with inflammation of the areas behind the eyes (cavernous sinus and superior orbital fissure).[citation needed]

Diagnosis

Tolosa–Hunt syndrome is usually diagnosed via exclusion, and as such a vast amount of laboratory tests are required to rule out other causes of the patient's symptoms.[3] These tests include a complete blood count, thyroid function tests and serum protein electrophoresis.[3] Studies of cerebrospinal fluid may also be beneficial in distinguishing between Tolosa–Hunt syndrome and conditions with similar signs and symptoms.[3]

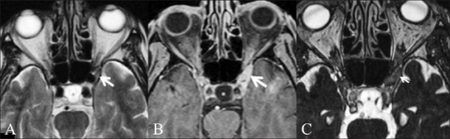

MRI scans of the brain and orbit with and without contrast, magnetic resonance angiography or digital subtraction angiography and a CT scan of the brain and orbit with and without contrast may all be useful in detecting inflammatory changes in the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure and/or orbital apex.[3] Inflammatory change of the orbit on cross sectional imaging in the absence of cranial nerve palsy is described by the more benign and general nomenclature of orbital pseudotumor.[citation needed]Sometimes a biopsy may need to be obtained to confirm the diagnosis, as it is useful in ruling out a neoplasm.[3] Other diagnoses to consider include craniopharyngioma, migraine and meningioma.[3]

Treatment

Treatment of Tolosa–Hunt syndrome includes immunosuppressives such as corticosteroids (often prednisolone) or steroid-sparing agents (such as methotrexate or azathioprine).[3]

Radiotherapy has also been proposed.[5]

Prognosis

The prognosis of Tolosa–Hunt syndrome is usually considered good. Patients usually respond to corticosteroids, and spontaneous remission can occur, although movement of ocular muscles may remain damaged.[3] Roughly 30–40% of patients who are treated for Tolosa–Hunt syndrome experience a relapse.[3]

Epidemiology

Tolosa–Hunt syndrome is uncommon internationally. There is one recorded case in New South Wales, Australia.[3] Both sexes, male and female, are affected equally, and it typically occurs around the age of 60.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Tolosa–Hunt syndrome". Who Named It. Archived from the original on 2018-08-15. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ La Mantia L, Curone M, Rapoport AM, Bussone G (2006). "Tolosa–Hunt syndrome: critical literature review based on IHS 2004 criteria". Cephalalgia. 26 (7): 772–81. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01115.x. PMID 16776691. S2CID 31366123.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Danette C Taylor, DO. "Tolosa–Hunt syndrome". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 2008-11-09. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Tolosa Hunt Syndrome". National Organization for Rare Disorders, Inc. Archived from the original on 2015-06-09. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ Foubert-Samier A, Sibon I, Maire JP, Tison F (2005). "Long-term cure of Tolosa–Hunt syndrome after low-dose focal radiotherapy". Headache. 45 (4): 389–91. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05077_5.x. PMID 15836581. S2CID 42261396.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |