Tick-borne encephalitis

| Tick-borne encephalitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: TBE | |

| |

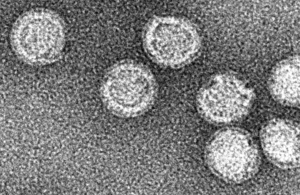

| Virus which causes tick-borne encephalitis | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Initial: None, fever, tiredness, headache, nausea[1] Later: Meningitis, encephalitis, myelitis[2] |

| Complications | Cognitive dysfunction[2] |

| Usual onset | 7 days[1] |

| Types | European, Far Eastern, Siberian[3] |

| Causes | Tick-borne encephalitis virus spread by tick bites[1] |

| Risk factors | Spending time outdoors near forests[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Detection of specific antibodies[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | West Nile, Usutu, Japanese encephalitis, Lyme[3] |

| Prevention | Tick-borne encephalitis vaccine, insect repellent, protective clothing[1] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[1] |

| Frequency | >10,000 cases/year[2] |

| Deaths | 1% to 20% depending on subtype[1][3] |

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is a viral infectious disease.[1] Many people have no symptoms while others develop fever, tiredness, headache, and nausea.[1] These initial symptoms last about 5 days and after a period without symptoms, may be followed by meningitis, encephalitis, or myelitis.[1][2] Onset is generally about 7 days after infection.[1] About a third of cases develop long term side effects, predominantly cognitive dysfunction.[2] Tick-borne encephalitis virus typically spreads to people through the bite of an infected tick and less commonly via eating unpasteurized dairy products from infected animals.[4] Risk factors include spending time outdoors near forests.[4] It does not spread between people.[1] Diagnosis is confirmed based on finding specific antibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid or blood.[1]

Prevention involves vaccination against the disease, using insect repellent, and wearing clothing to cover the skin.[1] If infected, management involves supportive care.[1] This may vary from rest and simple pain medication to hospitalization with breathing support.[5] The risk of deaths varies from about 1% with the European subtype to 20% with the Far Eastern subtype.[1][3]

Tick-borne encephalitis affects more than 10,000 people a year.[2] It primarily occurs in western and northern Europe and northern and eastern Asia.[4] In Europe, rates of disease have increased nearly 4 fold over the last three decades.[1] Infections most commonly occur in April through November.[4] The virus was first described in 1937.[3] Though descriptions of possible cases occur at least as far back as the 18th century.[2] A number of other animals including cows, goats, dogs, and bats may also be infected.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The disease is most often biphasic. After an incubation period of approximately one week (range: 4–28 days) from exposure (tick bite) non-specific symptoms occurs. These symptoms are fever, malaise, headache, nausea, vomiting and myalgias that persist for about 5 days.[2][1][6] Then, after approximately one week without symptoms, some of the infected develop neurological symptoms, i.e. meningitis, encephalitis or meningoencephalitis. Myelitis also occurs with or without encephalitis.[2][1][6][7]

Sequelae persists for a year or more in approximately one third of people who develop neurological disease. Most common long-term symptoms are headache, concentration difficulties, memory impairment and other symptoms of cognitive dysfunction.[2]

Mortality depends on the subtype of the virus. For the European subtype mortality rates are 0.5% to 2% for people who develop neurological disease.[1]

In dogs, the disease also manifests as a neurological disorder with signs varying from tremors to seizures and death.[8] In ruminants, neurological disease is also present, and animals may refuse to eat, appear lethargic, and also develop respiratory signs.[8]

Cause

TBE is caused by tick-borne encephalitis virus, a member of the genus Flavivirus in the family Flaviviridae. It was first isolated in 1937. Three virus sub-types also exist: European or Western tick-borne encephalitis virus (transmitted by Ixodes ricinus), Siberian tick-borne encephalitis virus (transmitted by I. persulcatus), and Far-Eastern tick-borne encephalitis virus, formerly known as Russian spring summer encephalitis virus (transmitted by I. persulcatus).[1][9]

Transmission

It is transmitted by the bite of several species of infected woodland ticks, including Ixodes scapularis, I. ricinus and I. persulcatus,[10] or (rarely) through the non-pasteurized milk of infected cows.[11]

Infection acquired through goat milk consumed as raw milk or raw cheese (Frischkäse) has been documented in 2016 and 2017 in the German state of Baden-Württemberg. None of the infected had neurological disease.[12]

-

Ixodes persulcatus

-

Sheep ticks (Ixodes ricinus), such as this engorged female, transmit the disease

Structure

TBEV is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus, contained in a 40 to 60 nm spherical, enveloped capsid.[13] The TBEV genome is approximately 11kb in size, which contains a 5' cap, a single open reading frame with 3' and 5' UTRs, and is without polyadenylation.[13] Like other flaviviruses,[14] the TBEV genome codes for ten viral proteins, three structural, and seven nonstructural.[15][13]

-

TBEV at different pH levels

-

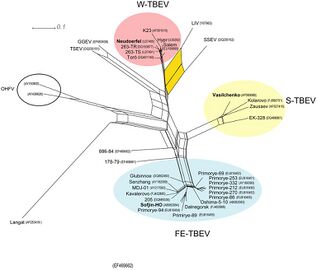

The three TBEV subtypes are highlighted in color and the positions of all prototype strains are indicated in bold.

Pathogenesis

With the exception of food-borne cases, infection begins in the skin at the site of the tick bite. Skin dendritic cells (DCs) are preferentially targeted.[15] Initially, the virus replicates locally and immune response is triggered when viral components are recognized by cytosolic pattern recognition receptors , such as Toll-like receptors.[16]

Recognition causes the release of cytokines including interferons (IFN) α, β , and γ and chemokines, attracting migratory immune cells to the site of the bite.[15] The infection may be halted at this stage and cleared, before the onset of noticeable symptoms. Tick saliva enhances infection by modulating host immune response, dampening apoptotic signals.[16] If the infection continues, migratory DCs and macrophages become infected and travel to the local draining lymph node where activation of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, monocytes and the complement system are activated.[16]

Diagnosis

Detection of specific IgM and IgG antibodies in patients sera combined with typical clinical signs, is the principal method for diagnosis. In more complicated situations, e.g. after vaccination, testing for presence of antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid may be necessary.[1] It has been stated that lumbar puncture always should be performed when diagnosing TBE and that pleocytosis in cerebrospinal fluid should be added to the diagnostic criteria.[17]

PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) method is rarely used, since TBE virus RNA is most often not present in patient sera or cerebrospinal fluid at the time of neurological symptoms.[17]

Prevention

Prevention includes non-specific (tick-bite prevention, tick checks) and specific prophylaxis in the form of a vaccination. Tick-borne encephalitis vaccines are very effective and available in many disease endemic areas and in travel clinics.[18]

Trade names are Encepur N[19] and FSME-Immun CC.[20]

Treatment

There is no specific antiviral treatment for TBE. Symptomatic brain damage requires hospitalization and supportive care based on syndrome severity. [21]

Anti-inflammatory drugs, such as corticosteroids, may be considered under specific circumstances for symptomatic relief. Intubation and respiratory support may be necessary.[22][23]

Epidemiology

As of 2011, the disease was most common in Central and Eastern Europe, and Northern Asia. About ten to twelve thousand cases are documented a year but the rates vary widely from one region to another.[24] Most of the variation has been the result of variation in host population, particularly that of deer. In Austria, an extensive vaccination program since the 1970s reduced the incidence in 2013 by roughly 85%.[25]

In Germany, during the 2010s, there have been a minimum of 95 (2012) and a maximum of 584 cases (2018) of TBE (or FSME as it is known in German). More than half of the reported cases from 2019 had meningitis, encephalitis or myelitis. The risk of infection was noted to be increasing with age, especially in people older than 40 years and it was greater in men than women. Most cases were acquired in Bavaria (46%) and Baden-Württemberg (37%), much less in Saxonia, Hesse, Niedersachsen and other states. Altogether 164 Landkreise are designated TBE-risk areas, including all of Baden-Württemberg except for the city of Heilbronn.[12]

In Sweden, most cases of TBE occur in a band running from Stockholm to the west, especially around lakes and the nearby region of the Baltic sea.[26][27] It reflects the greater population involved in outdoor activities in these areas. Overall, for Europe, the estimated risk is roughly 1 case per 10,000 human-months of woodland activity. Although in some regions of Russia and Slovenia, the prevalence of cases can be as high as 70 cases per 100,000 people per year.[25][28] Travelers to endemic regions do not often become cases, with only 5 cases reported among U.S. travelers returning from Eurasia between 2000 and 2011, a rate so low that as of 2016 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended vaccination only for those who will be extensively exposed in high risk areas.[29]

History

Though the first description of what may have been TBE appears in records in the 1700s in Scandinavia,[30] identification of the TBEV virus occurred in the Soviet Union in the 1930s.[31]

The investigation began due to an outbreak of what was believed to be Japanese encephalitis, the expedition was led by virologist Lev A. Zilber, who assembled a team of twenty young scientists in a number of related fields such as acarology, microbiology, neurology, and epidemiology.[32][2][31]

Inside the month of May, the expedition had identified ticks as the likely vector, collected I. persucatus ticks by exposure of bare skin by entomologist Alexander V. Gutsevich and virologist Mikhail P. Chumakov had isolated the virus from ticks feeding on intentionally infected mice.[2]

During the summer, five expeditions members became infected with TBEV, and while there were no fatalities, three of the five suffered damaging sequelae.[2]

Vaccine

The first European Tick-borne encephalitis vaccine became available to the public in 1976.[33]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 "Factsheet about tick-borne encephalitis (TBE)". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Lindquist, Lars; Vapalahti, Olli (2008-05-31). "Tick-borne encephalitis". The Lancet. 371 (9627): 1861–1871. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60800-4. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 18514730. S2CID 901857. Archived from the original on 2012-12-18. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Clinical Evaluation and Disease | Tick-borne encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 9 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) | Tick-borne encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 11 March 2022. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ "Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment | Tick-borne encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 14 October 2022. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Riccardi N (22 January 2019). "Tick-borne encephalitis in Europe: a brief update on epidemiology, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment". Eur J Intern Med. 62: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2019.01.004. PMID 30678880. S2CID 59252822.

- ↑ Kaiser R (September 2008). "Tick-borne encephalitis". Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 22 (3): 561–75, x. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2008.03.013. PMID 18755391.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Tickborne Encephalitis Virus Archived 2019-06-03 at the Wayback Machine reviewed and published by WikiVet, accessed 12 October 2011.

- ↑ "Tick-borne Encephalitis (TBE)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ↑ Dumpis U, Crook D, Oksi J (April 1999). "Tick-borne encephalitis". Clin. Infect. Dis. 28 (4): 882–90. doi:10.1086/515195. PMID 10825054.

- ↑ CDC Yellow Book Archived 2015-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 5 October 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "FSME: Risikogebiete in Deutschland" (PDF). Epidemiologisches Bulletin, RKI (in Deutsch). Berlin. 8. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-02-25. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Mansfield, K. L.; Johnson, N.; Phipps, L. P.; Stephenson, J. R.; Fooks, A. R.; Solomon, T. (2009-08-01). "Tick-borne encephalitis virus – a review of an emerging zoonosis". Journal of General Virology. 90 (8): 1781–1794. doi:10.1099/vir.0.011437-0. ISSN 0022-1317. PMID 19420159.

- ↑ Wilder-Smith, Annelies; Ooi, Eng-Eong; Horstick, Olaf; Wills, Bridget (January 2019). "Dengue". The Lancet. 393 (10169): 350–363. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32560-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 30696575. S2CID 208789595.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Ruzek, Daniel; Avšič Županc, Tatjana; Borde, Johannes; Chrdle, Ales; Eyer, Ludek; Karganova, Galina; Kholodilov, Ivan; Knap, Nataša; Kozlovskaya, Liubov; Matveev, Andrey; Miller, Andrew D.; Osolodkin, Dmitry I.; Överby, Anna K.; Tikunova, Nina; Tkachev, Sergey; Zajkowska, Joanna (1 April 2019). "Tick-borne encephalitis in Europe and Russia: Review of pathogenesis, clinical features, therapy, and vaccines". Antiviral Research. 164: 23–51. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.01.014. ISSN 0166-3542. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Velay, Aurélie; Paz, Magali; Cesbron, Marlène; Gantner, Pierre; Solis, Morgane; Soulier, Eric; Argemi, Xavier; Martinot, Martin; Hansmann, Yves; Fafi-Kremer, Samira (2019-07-04). "Tick-borne encephalitis virus: molecular determinants of neuropathogenesis of an emerging pathogen". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 45 (4): 472–493. doi:10.1080/1040841X.2019.1629872. ISSN 1040-841X. PMID 31267816. S2CID 195787988.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Taba, P.; Schmutzhard, E.; Forsberg, P.; Lutsar, I.; Ljøstad, U.; Mygland, Å.; Levchenko, I.; Strle, F.; Steiner, I. (October 2017). "EAN consensus review on prevention, diagnosis and management of tick-borne encephalitis". European Journal of Neurology. 24 (10): 1214–e61. doi:10.1111/ene.13356. PMID 28762591. S2CID 12844392.

- ↑ Demicheli V, Debalini MG, Rivetti A (2009). Demicheli V (ed.). "Vaccines for preventing tick-borne encephalitis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD000977. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000977.pub2. PMC 6532705. PMID 19160184.

- ↑ "Encepur® N". compendium.ch. 2016-04-28. Archived from the original on 2019-12-14. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- ↑ "FSME-Immun® CC". compendium.ch. 2017-08-11. Archived from the original on 2016-10-14. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- ↑ "Treatment & Prevention | Tick-borne encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 28 March 2022. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ↑ Bogovic, Petra (2015). "Tick-borne encephalitis: A review of epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 3 (5): 430. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i5.430. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ↑ Bonville, Cynthia; Domachowske, Joseph (2021). "Tick-Borne Encephalitis". Vaccines: A Clinical Overview and Practical Guide. Springer International Publishing. pp. 353–361. ISBN 978-3-030-58414-6. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ↑ "Vaccines against tick-borne encephalitis: WHO position paper" (PDF). Relevé Épidémiologique Hebdomadaire. 86 (24): 241–56. 10 June 2011. PMID 21661276. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Amicizia, Daniela; Domnich, Alexander; Panatto, Donatella; Lai, Piero Luigi; Cristina, Maria Luisa; Avio, Ulderico; Gasparini, Roberto (2013-05-14). "Epidemiology of tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) in Europe and its prevention by available vaccines". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 9 (5): 1163–1171. doi:10.4161/hv.23802. ISSN 2164-5515. PMC 3899155. PMID 23377671.

- ↑ Pettersson, John H.-O.; Golovljova, Irina; Vene, Sirkka; Jaenson, Thomas G. T. (2014-01-01). "Prevalence of tick-borne encephalitis virus in Ixodes ricinus ticks in northern Europe with particular reference to Southern Sweden". Parasites & Vectors. 7: 102. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-7-102. ISSN 1756-3305. PMC 4007564. PMID 24618209.

- ↑ team, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)-Health Communication Unit- Eurosurveillance editorial (2011). "Tick-borne encephalitis increasing in Sweden, 2011". Eurosurveillance. 16 (39). doi:10.2807/ese.16.39.19981-en. PMID 21968422.

- ↑ team, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)-Health Communication Unit- Eurosurveillance editorial (2011-03-11). "Case report: Tick-borne encephalitis in two Dutch travellers returning from Austria, Netherlands, July and August 2011". Eurosurveillance. 16 (44): 20003. doi:10.2807/ese.16.44.20003-en. PMID 22085619. Archived from the original on 2017-07-29. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- ↑ "Tickborne Encephalitis - Chapter 3 - 2016 Yellow Book | Travelers' Health | CDC". wwwnc.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-06-11. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- ↑ Blom, Kim; Cuapio, Angelica; Sandberg, J. Tyler; Varnaite, Renata; Michaëlsson, Jakob; Björkström, Niklas K.; Sandberg, Johan K.; Klingström, Jonas; Lindquist, Lars; Gredmark Russ, Sara; Ljunggren, Hans-Gustaf (2018). "Cell-Mediated Immune Responses and Immunopathogenesis of Human Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus-Infection". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 2174. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02174. ISSN 1664-3224. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Zlobin, Vladimir I.; Pogodina, Vanda V.; Kahl, Olaf (1 October 2017). "A brief history of the discovery of tick-borne encephalitis virus in the late 1930s (based on reminiscences of members of the expeditions, their colleagues, and relatives)". Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 8 (6): 813–820. doi:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.05.001. ISSN 1877-959X. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ Uspensky, Igor (May 2018). "Several words in addition to "A brief history of the discovery of tick-borne encephalitis virus in the late 1930s" by V.I. Zlobin, V.V. Pogodina and O. Kahl (TTBDIS, 2017, 8, 813–820)". Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 9 (4): 834–835. doi:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.03.007. PMID 29559213.

- ↑ Kollaritsch, Herwig; Heininger, Ulrich (2021). "16. Tick-borne encephalitis vaccines". In Vesikari, Timo; Damme, Pierre Van (eds.). Pediatric Vaccines and Vaccinations: A European Textbook (Second ed.). Switzerland: Springer. pp. 159–170. ISBN 978-3-030-77172-0. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Tickborne encephalitis Archived 2019-06-15 at the Wayback Machine at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Factsheet Archived 2021-03-23 at the Wayback Machine from Viral Special Pathogens Branch at the CDC