Superior mesenteric artery syndrome

| Superior mesenteric artery syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Wilkie syndrome, mesenteric root syndrome, chronic duodenum ileus, Cast syndrome, arteriomesenteric duodenal obstruction[1] | |

| |

| Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scan showing duodenal compression (black arrow) by the superior mesenteric artery (red arrow) and the abdominal aorta (blue arrow). | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, general surgery |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, fullness, nausea, vomiting, weight loss[2] |

| Complications | Small bowel obstruction, pneumatosis intestinalis[2] |

| Risk factors | Significant weight loss, surgery for scoliosis, genetics[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and medical imaging after other potential causes are excluded[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Anorexia, bulimia, peptic ulcer disease, irritable bowel syndrome, other causes of gastroparesis[1] |

| Treatment | Gaining weight, sitting with the knees to the chest after eating, surgery[2] |

| Frequency | 2 per 1,000 people[1] |

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome is a digestive condition that occurs when the first part of the small intestine (duodenum) is compressed between two arteries (the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery).[2] Symptoms may include abdominal pain, rapid fullness when eating, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss.[2] Complications may include small bowel obstruction, electrolyte abnormalities, and pneumatosis intestinalis.[2]

Causes may include significant weight loss or following surgery for scoliosis.[2] Cases may run in families.[2] The underlying mechanism often involves the loss of the fatty tissue that surrounds the superior mesenteric artery.[2] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms and medical imaging after other potential causes are excluded.[2] Nutcracker syndrome is a different condition in which the left renal vein is compressed by an artery.[3]

Treatment may involve gaining weight, sitting with the knees to the chest after eating, or surgery.[2] Small and frequent meals may be helpful.[2] Tube feeding or intravenous nutritional support may be required in severe cases.[2] Metoclopramide may be used to help with nausea.[2] Surgery is generally only considered if other measures are not effected.[2] SMA is estimated to affect about 2 per 1,000 people.[1] It was first described in 1861 by Carl von Rokitansky.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms include early satiety, nausea, vomiting, extreme "stabbing" postprandial abdominal pain (due to both the duodenal compression and the compensatory reversed peristalsis), abdominal distention/distortion, burping, external hypersensitivity or tenderness of the abdominal area, reflux, and heartburn.[5] In infants, feeding difficulties and poor weight gain are also frequent symptoms.[6]

In some cases of SMA syndrome, severe malnutrition accompanying spontaneous wasting may occur.[7] This, in turn, increases the duodenal compression, which worsens the underlying cause, creating a cycle of worsening symptoms.[8]

Fear of eating is a commonly seen among those with the chronic form of SMA syndrome. For many, symptoms are partially relieved when in the left lateral decubitus or knee-to-chest position, or in the prone (face down) position. A Hayes maneuver, which corresponds to applying pressure below the umbilicus in cephalad and dorsal direction, elevates the root of the SMA, also slightly easing the constriction. Symptoms can be aggravated when leaning to the right or taking a face up position.[7]

Causes

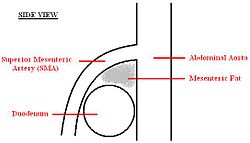

Retroperitoneal fat and lymphatic tissue normally serve as a cushion for the duodenum, protecting it from compression by the SMA. SMA syndrome is thus triggered by any condition involving an insubstantial cushion and narrow mesenteric angle. SMA syndrome can present in two forms: chronic/congenital or acute/induced.

Patients with the chronic, congenital form of SMA syndrome predominantly have a lengthy or even lifelong history of abdominal complaints with intermittent exacerbations depending on the degree of duodenal compression. Risk factors include anatomic characteristics such as: aesthenic (very thin or "lanky") body build, an unusually high insertion of the duodenum at the ligament of Treitz, a particularly low origin of the SMA, or intestinal malrotation around an axis formed by the SMA.[9] Predisposition is easily aggravated by any of the following: poor motility of the digestive tract,[10] retroperitional tumors, loss of appetite, malabsorption, cachexia, exaggerated lumbar lordosis, visceroptosis, abdominal wall laxity, peritoneal adhesions, abdominal trauma,[11] rapid linear adolescent growth spurt, weight loss, starvation, catabolic states (as with cancer and burns), and history of neurological injury.[12]

The acute form of SMA syndrome develops rapidly after traumatic incidents that forcibly hyper-extend the SMA across the duodenum, inducing the obstruction, or sudden weight loss for any reason. Causes include prolonged supine bed rest, scoliosis surgery, left nephrectomy, ileo-anal pouch surgery.

It is important to note, however, that while SMA syndrome can mimic an eating disorder, distinguishing the two conditions is extremely important, as misdiagnosis in this situation can be dangerous.

-

A diagram of a healthy mesenteric angle.

-

A diagram of a compressed duodenum due to a reduced mesenteric angle.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is can be difficult, and usually one of exclusion. SMA syndrome is generally considered only after people have undergone an extensive evaluation of their gastrointestinal tract including upper endoscopy, and evaluation for various malabsorptive, ulcerative and inflammatory instestinal conditions with a higher diagnostic frequency. Diagnosis may follow X-ray examination revealing duodenal dilation followed by abrupt constriction proximal to the overlying SMA, as well as a delay in transit of four to six hours through the gastroduodenal region. Standard diagnostic exams include abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan with oral and IV contrast, upper gastrointestinal series (UGI), and, for equivocal cases, hypotonic duodenography. In addition, vascular imaging studies such as ultrasound and contrast angiography may be used to indicate increased bloodflow velocity through the SMA or a narrowed SMA angle.[13][14]

It is typically caused by an angle of 6°–25° between the AA and the SMA, in comparison to the normal range of 38°–56°, due to a lack of retroperitoneal and visceral fat (mesenteric fat). In addition, the aortomesenteric distance is 2–8 millimeters, as opposed to the typical 10–20.[15] However, a narrow SMA angle alone is not enough to make a diagnosis, because people can have a narrow SMA angle with no symptoms of SMA syndrome.[16]

Despite multiple case reports, there has been controversy surrounding the diagnosis and even the existence of SMA syndrome since symptoms do not always correlate well with radiologic findings, and may not always improve following surgical correction.[17] However, the reason for the persistence of gastrointestinal symptoms even after surgical correction in some cases has been traced to the remaining prominence of reversed peristalsis in contrast to direct peristalsis.[18]

Since females between the ages of 10 and 30 are most frequently afflicted, it is not uncommon for physicians to initially and incorrectly assume that emaciation is a choice of the patient instead of a consequence of SMA syndrome. Patients in the earlier stages of SMA syndrome often remain unaware that they are ill until substantial damage to their health is done, since they may attempt to adapt to the condition by gradually decreasing their food intake or naturally gravitating toward a lighter and more digestible diet.

-

Upper gastrointestinal series showing extreme duodenal dilation (white arrow) abruptly preceding constriction by the SMA.

-

Ultrasound showing SMA syndrome[19]

-

Ultrasound showing SMA syndrome[19]

Treatment

SMA syndrome can present in acute, acquired form (e.g. abruptly emerging within an inpatient stay following scoliosis surgery) as well as chronic form (i.e. developing throughout the course of a lifetime and advancing due to environmental triggers, life changes, or other illnesses). According to a number of recent sources, at least 70% of cases can typically be treated with medical treatment, while the rest require surgical treatment.[5][12][20]

Medical treatment is attempted first in many cases. In some cases, emergency surgery is necessary upon presentation.[12] A six-week trial of medical treatment is recommended in pediatric cases.[5] The goal of medical treatment for SMA syndrome is resolution of underlying conditions and weight gain. Medical treatment may involve nasogastric tube placement for duodenal and gastric decompression, mobilization into the prone or left lateral decubitus position,[21] the reversal or removal of the precipitating factor with proper nutrition and replacement of fluid and electrolytes, either by surgically inserted jejunal feeding tube, nasogastric intubation, or peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC line) administering total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Pro-motility agents such as metoclopramide may also be beneficial.[22] Symptoms may improve after restoration of weight, except when reversed peristalsis persists, or if regained fat refuses to accumulate within the mesenteric angle.[18] Most patients seem to benefit from nutritional support with hyperalimentation irrespective of disease history.[23]

If medical treatment fails, or is not feasible due to severe illness, surgical intervention is required. The most common operation for SMA syndrome, duodenojejunostomy, was first proposed in 1907 by Bloodgood.[7] Performed as either an open surgery or laparoscopically, duodenojejunostomy involves the creation of an anastomosis between the duodenum and the jejunum,[24] bypassing the compression caused by the AA and the SMA.[15] Less common surgical treatments for SMA syndrome include Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy, gastrojejunostomy, anterior transposition of the third portion of the duodenum, intestinal derotation, division of the ligament of Treitz (Strong's operation), and transposition of the SMA.[25] Both transposition of the SMA and lysis of the duodenal suspensory muscle have the advantage that they do not involve the creation of an intestinal anastomosis.[9]

The possible persistence of symptoms after surgical bypass can be traced to the remaining prominence of reversed peristalsis in contrast to direct peristalsis, although the precipitating factor (the duodenal compression) has been bypassed or relieved. Reversed peristalsis has been shown to respond to duodenal circular drainage—a complex and invasive open surgical procedure originally implemented and performed in China.[18]

In some cases, SMA syndrome may occur alongside a serious, life-threatening condition such as cancer or AIDS. Even in these cases, though, treatment of the SMA syndrome can lead to a reduction in symptoms and an increased quality of life.[26][27]

Prognosis

Delay in the diagnosis of SMA syndrome can result in fatal catabolysis (advanced malnutrition), dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, hypokalemia, acute gastric rupture or intestinal perforation (from prolonged mesenteric ischemia), gastric distention, spontaneous upper gastrointestinal bleeding, hypovolemic shock, and aspiration pneumonia. [15][13][28]

A 1-in-3 mortality rate for Superior Mesenteric Artery syndrome has been quoted by a small number of sources.[29] However, after extensive research, original data establishing this mortality rate has not been found, indicating that the number is likely to be unreliable. While research establishing an official mortality rate may not exist, two recent studies of SMA syndrome patients, one published in 2006 looking at 22 cases[12] and one in 2012 looking at 80 cases,[20] show mortality rates of 0%[12] and 6.3%,[20] respectively. According to the doctors in one of these studies, the expected outcome for SMA syndrome treatment is generally considered to be excellent.[12]

Epidemiology

According to a 1956 study, 0.3% of people referred for an upper-gastrointestinal-tract barium studies fit this diagnosis, and is thus a rare disease.[30] Recognition of SMA syndrome as a distinct clinical entity is controversial, due in part to its possible confusion with a number of other conditions,[31] though it is now widely acknowledged.[15] However, unfamiliarity with this condition in the medical community coupled with its intermittent and nonspecific symptomatology probably results in its underdiagnosis.[32]

As the syndrome involves a lack of essential fat, more than half of those diagnosed are underweight, sometimes to the point of sickliness and emaciation. Females are impacted more often than males, and while the syndrome can occur at any age, it is most frequently diagnosed in early adulthood. The most common co-morbid conditions include mental and behavioral disorders including eating disorders and depression, infectious diseases including tuberculosis and acute gastroenteritis, and nervous system diseases including muscular dystrophy, Parkinson's disease, and cerebral palsy.[20]

History

SMA syndrome was first described in 1861 by Carl Freiherr von Rokitansky in victims at autopsy, but remained pathologically undefined until 1927 when Wilkie published the first comprehensive series of 75 patients.[33]

Society and culture

American actor, director, producer, and writer Christopher Reeve had the acute form of SMA syndrome as a result of spinal cord injury.

Non-profit

In 2017 a US non-profit began distributing grants to those with SMAS. They are registered to the IRS under the name Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome Research, Awareness and Support, but also work under the DBA of SMAS Patient Assistance. It is their goal to assist the uninsured and under-insured in the U.S. receive the medical help they need to treat their SMAS.[34]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 "Superior mesenteric artery syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ↑ "Renal nutcracker syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ↑ Coley, Brian D. (2018). Caffey's Pediatric Diagnostic Imaging E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 979. ISBN 978-0-323-55347-6. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Shin, M. S.; Kim, J. Y. (2013). "Optimal duration of medical treatment in superior mesenteric artery syndrome in children". Journal of Korean Medical Science. 28 (8): 1220–5. doi:10.3346/jkms.2013.28.8.1220. PMC 3744712. PMID 23960451.

- ↑ Okugawa, Y.; Inoue, M.; Uchida, K.; Kawamoto, A.; Koike, Y.; Yasuda, H.; Kusunoki, M. (2007). "Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in an infant: Case report and literature review". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 42 (10): e5–e8. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.07.002. PMID 17923187.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Baltazar U, Dunn J, Floresguerra C, Schmidt L, Browder W (2000). "Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: an uncommon cause of intestinal obstruction". South. Med. J. 93 (6): 606–8. doi:10.1097/00007611-200006000-00014. PMID 10881780.Free full text with registration Archived 2003-10-07 at the Wayback Machine at Medscape

- ↑ "S: Superior mesenteric artery syndrome". GASTROLAB Digestive Dictionary. GASTROLAB. April 1, 2008. Archived from the original on March 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-20. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Laffont I, Bensmail D, Rech C, Prigent G, Loubert G, Dizien O (2002). "Late superior mesenteric artery syndrome in paraplegia: case report and review". Spinal Cord. 40 (2): 88–91. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3101255. PMID 11926421.

- ↑ Falcone, Kevin L.; Garrett, Kevin O. (July 2010). "Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome After Blunt Abdominal Trauma: A Case Report". Vasc Endovascular Surg. 44 (5): 410–412. doi:10.1177/1538574410369390. PMID 20484075. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Biank, V.; Werlin, S. (2006). "Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in children: A 20-year experience". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 42 (5): 522–525. doi:10.1097/01.mpg.0000221888.36501.f2. PMID 16707974.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Errico, Thomas J. "Surgical Management of Spinal Deformities", 458

- ↑ Buresh Christopher T.; Graber Mark A. (2006). "Unusual Causes of Recurrent Abdominal Pain". Emerg Med. 38 (5): 11–18. Archived from the original on 2009-05-09. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Shetty, A. K.; Schmidt-Sommerfeld, E.; Haymon, M. L.; Udall, J. N. (2000). "Radiologica case of the month: Denouement and discussion: Superior mesenteric artery syndrome". Archives of Family Medicine. 9 (1): 17. doi:10.1001/archfami.9.1.17.

- ↑ Arthurs, O. J.; Mehta, U. (2012). "Nutcracker and SMA syndromes: What is the normal SMA angle in children?". European Journal of Radiology. 81 (8): e854-61. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.04.010. PMID 22579528.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2008-10-25. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Yang, Wei-Liang and Xin-Chen Zhang. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2008 January 14; 14(2): 303-306 http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/14/303.pdf Archived 2012-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "UOTW #21 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 8 October 2014. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Lee, T. H.; Lee, J. S.; Jo, Y.; Park, K. S.; Cheon, J. H.; Kim, Y. S. (2012). "Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: Where do we stand today?". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 16 (12): 2203–2211. doi:10.1007/s11605-012-2049-5. PMID 23076975. Archived from the original on 2019-09-27. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- ↑ Dietz UA, Debus ES, Heuko-Valiati L, Valiati W, Friesen A, Fuchs KH, Malafaia O, Thiede A: Aorto-mesenteric artery compression syndrome. Chirurg 2000;71:1345–51

- ↑ Chark. "Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome". Everything2.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-19. Retrieved 2014-10-12.

- ↑ Lippl F, Hannig C, Weiss W, Allescher HD, Classen M, Kurjak M (2002). "Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: diagnosis and treatment from the gastroenterologist's view". J Gastroenterol. 37 (8): 640–3. doi:10.1007/s005350200101. PMID 12203080.

- ↑ "Duodenojejunostomy". The Free Dictionary. Farlex. Archived from the original on 2018-07-30. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ↑ Pourhassan, S.; Grotemeyer, D.; Fürst, G.; Rudolph, J.; Sandmann, W. (2008). "Infrarenal transposition of the superior mesenteric artery: A new approach in the surgical therapy for wilkie syndrome". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 47 (1): 201–204. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2007.07.037. PMID 17949939.

- ↑ Lippl, F.; Hannig, C.; Weiss, W.; Allescher, H.; Classen, M.; Kurjak, M. (2002). "Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: Diagnosis and treatment from the gastroenterologist's view". Journal of Gastroenterology. 37 (8): 640–643. doi:10.1007/s005350200101. PMID 12203080.

- ↑ Hoffman, R. J.; Arpadi, S. M. (2000). "A pediatric AIDS patient with superior mesenteric artery syndrome". AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 14 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1089/108729100318073. PMID 12240880.

- ↑ Kai-Hsiung Ko; Shih-Hung Tsai; Chih-Yung Yu; Guo-Shu Huang; Chang-Hsien Liu; Wei-Chou Chang. http://www.biomedsearch.com/nih/Unusual-complication-superior-mesenteric-artery/19181598.html Archived 2019-12-13 at the Wayback Machine"

- ↑ Capitano, S.; Donatelli, G.; Boccoli, G. (2012). "Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome—Believe in it! Report of a Case". Case Reports in Surgery. 2012: 282646. doi:10.1155/2012/282646. PMC 3420085. PMID 22919531.

- ↑ Goin, L. S.; Wilk, S.P. (1956). "Intermittent arteriomesenteric occlusion of the duodenum". Radiology. 67 (5): 729–737. doi:10.1148/67.5.729. PMID 13370885.

- ↑ Cohen LB, Field SP, Sachar DB (1985). "The superior mesenteric artery syndrome. The disease that isn't, or is it?". J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 7 (2): 113–6. doi:10.1097/00004836-198504000-00002. PMID 4008904.

- ↑ Hoffman, Robert J. and Stephen M. Arpadi. "Case Report: A Pediatric AIDS Patient with Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome." http://www.liebertonline.com/doi/abs/10.1089/108729100318073 Archived 2021-08-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Welsch T, Büchler MW, Kienle P (2007). "Recalling superior mesenteric artery syndrome". Dig Surg. 24 (3): 149–56. doi:10.1159/000102097. PMID 17476104. Archived from the original on 2019-05-18. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ↑ "Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome". Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

![Ultrasound showing SMA syndrome[19]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1f/UOTW_21_-_Ultrasound_of_the_Week_2.jpg/250px-UOTW_21_-_Ultrasound_of_the_Week_2.jpg)