Stunted growth

| Stunted growth | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Stunting, nutritional stunting | |

| |

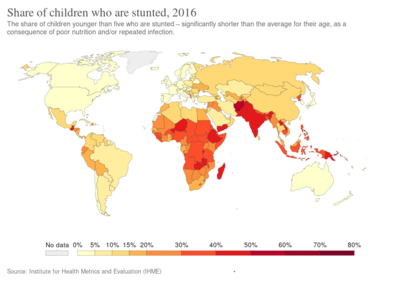

| World map of stunted growth for children in different countries (percentage moderate and severe stunting, 1995-2007) | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

Stunted growth is a reduced growth rate in human development. It is a primary manifestation of malnutrition (or more precisely undernutrition) and recurrent infections, such as diarrhea and helminthiasis, in early childhood and even before birth, due to malnutrition during fetal development brought on by a malnourished mother. The definition of stunting according to the World Health Organization (WHO) is for the "height for age" value to be less than two standard deviations of the WHO Child Growth Standards median.[1]

As of 2012 an estimated 162 million children under 5 years of age, or 25%, were stunted. More than 90% of the world's stunted children live in Africa and Asia, where respectively 36% and 56% of children are affected.[2] Once established, stunting and its effects typically become permanent. Stunted children may never regain the height lost as a result of stunting, and most children will never gain the corresponding body weight. Living in an environment where many people defecate in the open due to lack of sanitation, is an important cause of stunted growth in children, for example in India.[3]

Health effects

Stunted growth in children has the following public health impacts apart from the obvious impact of shorter stature of the person affected:

- greater risk for illness and premature death[1]

- may result in delayed mental development and therefore poorer school performance and later on reduced productivity in the work force[1]

- reduced cognitive capacity

- Women of shorter stature have a greater risk for complications during child birth due to their smaller pelvis, and are at risk of delivering a baby with low birth weight[1]

- Stunted growth can even be passed on to the next generation (this is called the "intergenerational cycle of malnutrition")[1]

The impact of stunting on child development has been established in multiple studies.[4] If a child is stunted at age 2 they will have higher risk of poor cognitive and educational achievement in life, with subsequent socio-economic and inter-generational consequences.[5][4] Multi-country studies have also suggested that stunting is associated with reductions in schooling, decreased economic productivity and poverty.[6] Stunted children also display higher risk of developing chronic non-communicable conditions such as diabetes and obesity as adults.[5][6] If a stunted child undergoes substantial weight gain after age 2, there is a higher chance of becoming obese. This is believed to be caused by metabolic changes produced by chronic malnutrition, that can produce metabolic imbalances if the individual is exposed to excessive or poor quality diets as an adult.[5][6] This can lead to higher risk of developing other related non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, metabolic syndrome and stroke.[5][6] At societal level, stunted individuals do not fulfill their physical and cognitive developmental potential and will not be able to contribute maximally to society. Stunting can therefore limit economic development and productivity, and it has been estimated that it can affect a country's GDP up to 3%.[5][4][6]

Causes

The causes for stunting are principally very similar if not the same as the causes for malnutrition in children. Most stunting happens during the 1,000-day period that spans from conception to a child's second birthday.[citation needed] The three main causes of stunting in South Asia, and probably in most developing countries, are poor feeding practices, poor maternal nutrition, and poor sanitation.

Feeding practices

Inadequate complementary child feeding and a general lack of vital nutrients beside pure caloric intake is one cause for stunted growth. Children need to be fed diets which meet the minimum requirements in terms of frequency and diversity in order to prevent undernutrition.[7] Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended for the first six months of life and complementary feeding of nutritious food alongside breastfeeding for children aged six months to 2-years-old. Prolonged exclusive breastfeeding is associated with undernutrition because breast milk alone is nutritionally insufficient for children over six months old.[8][9] Prolonged breastfeeding with inadequate complementary feeding leads to growth failure due to insufficient nutrients which are essential for childhood development. The relationship between undernutrition and prolonged duration of breastfeeding is mostly observed among children from poor households and whose parents are uneducated as they are more likely to continue breast-feeding without meeting minimum dietary diversity requirement.[10]

Maternal nutrition

Poor maternal nutrition during pregnancy and breastfeeding can lead to stunted growth of their children. Proper nutrition for mothers during the prenatal and postnatal period is important for ensuring healthy birth weight and for healthy childhood growth. Prenatal causes of child stunting are associated with maternal undernutrition. Low maternal BMI predisposes the fetus to poor growth leading to intrauterine growth retardation, which is strongly associated with low birth weight and size.[11] Women who are underweight or anemic during pregnancy, are more likely to have stunted children which perpetuates the inter-generational transmission of stunting. Children born with low birthweight are more at risk of stunting.[7] However, the effect of prenatal undernutrition can be addressed during the postnatal period through proper child feeding practices.[11]

Sanitation

There is most likely a link between children's linear growth and household sanitation practices. The ingestion of high quantities of fecal bacteria by young children through putting soiled fingers or household items in the mouth leads to intestinal infections. This affect children's nutritional status by diminishing appetite, reducing nutrient absorption, and increasing nutrient losses.

The diseases recurrent diarrhea and intestinal worm infections (helminthiasis) which are both linked to poor sanitation have been shown to contribute to child stunting. The evidence that a condition called environmental enteropathy also stunts children is not conclusively available yet, although the link is plausible and several studies are underway on this topic.[12][13][14] Environmental enteropathy is a syndrome causing changes in the small intestine of persons and can be brought on due to lacking basic sanitary facilities and being exposed to faecal contamination on a long-term basis.[12][15][16]

Research on a global level has found that the proportion of stunting that could be attributed to five or more episodes of diarrhoea before two years of age was 25%.[17] Since diarrhoea is closely linked with water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), this is a good indicator for the connection between WASH and stunted growth. To what extent improvements in drinking water safety, toilet use and good handwashing practices contribute to reduce stunting depends on the how bad these practices were prior to interventions.

Diagnosis

Growth stunting is identified by comparing measurements of children's heights to the World Health Organization 2006 growth reference population: children who fall below the fifth percentile of the reference population in height for age are defined as stunted, regardless of the reason. The lower than fifth percentile corresponds to less than two standard deviations of the WHO Child Growth Standards median.

As an indicator of nutritional status, comparisons of children's measurements with growth reference curves may be used differently for populations of children than for individual children. The fact that an individual child falls below the fifth percentile for height for age on a growth reference curve may reflect normal variation in growth within a population: the individual child may be short simply because both parents carried genes for shortness and not because of inadequate nutrition. However, if substantially more than 5% of an identified child population have height for age that is less than the fifth percentile on the reference curve, then the population is said to have a higher-than-expected prevalence of stunting, and malnutrition is generally the first cause considered.

Prevention

Three main things are needed to reduce stunting:[18]

- a kind of environment where political commitment can thrive (also called an "enabling environment")

- applying several nutritional modifications or changes in a population on a large scale which have a high benefit and a low cost

- a strong foundation that can drive change (food security, and a supportive health environment through increasing access to safe water and sanitation).

To prevent stunting, it is not just a matter of providing better nutrition but also access to clean water, improved sanitation (hygienic toilets) and hand washing at critical times (summarised as "WASH"). Without provision of toilets, prevention of tropical intestinal diseases, which may affect almost all children in the developing world and lead to stunting will not be possible.[19]

Studies have looked at ranking the underlying determinants in terms of their potency in reducing child stunting and found in the order of potency:[20]

- percent of dietary energy from non-staples (greatest impact)

- access to sanitation and women's education

- access to safe water

- per capita dietary energy supply

Three of these determinants should receive attention in particular: access to sanitation, and diversity of calorie sources from food supplies, . A study by the Institute of Development Studies has stressed that: "The first two should be prioritized because they have strong impacts yet are farthest below their desired levels".[20]

The goal of UN agencies, governments and NGO is now to optimise nutrition during the first 1000 days of a child's life, from pregnancy to the child's second birthday, in order to reduce the prevalence of stunting.[21] The first 1000 days in a child's life are a crucial "window of opportunity" because the brain develops rapidly, laying the foundation for future cognitive and social ability.[22] Furthermore, it is also the time when young children are the most at risk of infections that lead to diarrhoea. It is the time when they stop breast feeding (weaning process), begin to crawl, put things in their mouths and become exposed to faecal matter from open defecation and environmental enteropathies.[21]

Pregnant and lactating mothers

Ensuring proper nutrition of pregnant and lactating mothers is essential.[4] Achieving so by helping women of reproductive age be in good nutritional status at conception is an excellent preventive measure.[4] A focus on the pre-conception period has recently been introduced as a complement to the key phase of the 1000 days of pregnancy and first two years of life.[4] An example of this is are attempts to control anemia in women of reproductive age.[4] A well-nourished mother is the first step of stunting prevention, decreasing chances of the baby being born of low birth-weight, which is the first risk factor for future malnutrition.[4]

After birth, in terms of interventions for the child, early initiation of breastfeeding, together with exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months, are pillars of stunting prevention.[4] Introducing proper complementary feeding after 6 months of age together with breastfeeding until age 2 is the next step.[4]

Policy interventions

In summary, key policy interventions for the prevention of stunting are:

- Improvement in nutrition surveillance activities to identify rates and trends of stunting and other forms of malnutrition within countries.[4] This should be done with an equity perspective, as it is likely that stunting rates will vary greatly between different population groups. The most vulnerable should be prioritized. The same should be done for risk factors such as anemia, maternal under-nutrition, food insecurity, low birth-weight, breastfeeding practices etc. By collecting more detailed information, it is easier to ensure that policy interventions really address the root causes of stunting.

- Political will to develop and implement national targets and strategies in line with evidence-based international guidelines as well as contextual factors.[4]

- Designing and implementing policies promoting nutritional and health well-being of mothers and women of reproductive age.[4] The main focus should be on the 1000 days of pregnancy and first two years of life, but the pre-conception period should not be neglected as it can play a significant role in ensuring the fetus and baby's nutrition.

- Designing and implementing policies promoting proper breastfeeding and complementary feeding practice[4] (focusing on diet diversity for both macro and micronutrients). This can ensure optimal infant nutrition as well as protection from infections that can weaken the child's body. Labor policy ensuring mothers have the chance to breastfeed should be considered where necessary.

- Introducing interventions addressing social and other health determinants of stunting, such as poor sanitation and access to drinking water, early marriages, intestinal parasite infections, malaria and other childhood preventable disease[4] (referred to as “nutrition-sensitive interventions”), as well as the country's food security landscape. Interventions to keep adolescent girls in school can be effective at delaying marriage with subsequent nutritional benefits for both women and babies.[4] Regulating milk substitutes is also very important to ensure that as many mothers as possible breastfeed their babies, unless a clear contraindication is present.[4]

- Broadly speaking, effective policies to reduce stunting require multisectoral approaches, strong political commitment, community involvement and integrated service delivery.[4]

Epidemiology

According to the World Health organisation if less than 20% of the population is affected by stunting, this is regarded as "low prevalence" in terms of public health significance.[1] Values of 40% or more are regarded as very high prevalence, and values in between as medium to high prevalence.[1]

UNICEF has estimated that: "Globally, more than one quarter (26 per cent) of children under 5 years of age were stunted in 2011 – roughly 165 million children worldwide."[23] and "In sub-Saharan Africa, 40 per cent of children under 5 years of age are stunted; in South Asia, 39 per cent are stunted."[23] The four countries with the highest prevalence are Timor-Leste, Burundi, Niger and Madagascar where more than half of children under 5 years old are stunted.[23]

Trends

As of 2015, it was estimated that there were 156 million stunted children under 5 in the world, 90% of them living in low and low-middle income countries.[24] 56% of these were in Asia, and 37% in Africa.[24] It is possible that some of these children concurrently had other forms of malnutrition, including wasting and stunting, and overweight and stunting. No statistics are currently available for these combined conditions. Stunting has been on the decline for the past 15 years, but this decline has been too slow. As a comparison, there were 255 million stunted children in 1990, 224 in 1995, 198 in 2000, 182 in 2005, 169 in 2010, and 156 in 2016.[24] The decline is happening, but it is uneven geographically, it is unequal among different groups in society, and prevalence of stunting remains at unacceptably high numbers.[24] Too many children who are not able to fulfill their genetic physical and cognitive developmental potential. A research paper published in January 2020, which mapped stunting, wasting and underweight in children in low- and middle-income countries, predicted that only five countries would meet global targets for reducing malnutrition by 2025 in all second administrative subdivisions.[25]

Over the period 2000–2015, Asia reduced its stunting prevalence from 38 to 24%, Africa from 38 to 32%, and Latin America and the Caribbean from 18 to 11%.[24] This equates to a relative reduction of 36, 17 and 39% respectively, indicating that Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean have displayed much larger improvements than Africa, which needs to address this issue with much more effort if it is to win the battle against a problem that has been crippling its development for decades. Of these regions, Latin America and the Caribbean are on track to achieve global targets set with global initiatives such as the United Nations Millennium Development Goals and the World Health Assembly targets (see following section on global targets).[24]

Sub-regional stunting rates are as follows: In Africa, the highest rates are observed in East Africa (37.5%).[24] All other Sub-Saharan sub-regions also have high rates, with 32.1% in West Africa, 31.2% in Central Africa, and 28.4% in Southern Africa.[24] North Africa is at 18%, and the Middle East at 16.2%.[24] In Asia, the highest rate is observed in South Asia at 34.4%.[24] South-East Asia is at 26.3%. Pacific Islands also display a high rate at 38.2%. Central and South America are respectively at 15.6 and 9.9%.[24] South Asia, given its very high population at over 1 billion and high prevalence rate of stunting, is the region currently hosting the highest absolute number of children with stunting[24] (60 million plus).

Looking at absolute numbers of children under 5 affected by stunting, it is obvious why current efforts and reductions are insufficient. The absolute number of stunted children has increased in Africa from 50.4 to 58.5 million in the time 2000–2015.[24] This is despite the reduction in percentage prevalence of stunting, and is due to the high rates of population growth. The data therefore indicate that the rate of reduction of stunting in Africa has not been able to counterbalance the increased number of growing children that fall into the trap of malnutrition, due to population growth in the region. This is also true in Oceania, unlike Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean where substantial absolute reductions in the number of stunted children have been observed[24] (for example, Asia reduced its number of stunted children from 133 million to 88 million between 2000 and 2015).

The reduction in stunting is closely linked to poverty reduction and the will and ability of governments to set up solid multisectoral approaches to reduce chronic malnutrition. Low income countries are the only group with more stunted children today than in the year 2000.[24] Conversely, all other countries (high-income, upper-middle income, lower-middle income) have achieved reductions in the numbers of stunted children.[24] This sadly perpetuates a vicious cycle of poverty and malnutrition, whereby malnourished children are not able to maximally contribute to economic development as adults, and poverty increases chances of malnutrition.

Research

The Water and Sanitation Program of the World Bank has investigated links between lack of sanitation and stunting in Vietnam and Lao PDR.[26] For example, in Vietnam it was found that lack of sanitation in rural villages in mountainous regions of Vietnam led to five-year-old children being 3.7 cm shorter than healthy children living in villages with good access to sanitation.[26] This difference in height is irreversible and matters a great deal for a child's cognitive development and future productive potential.

Review articles

The Lancet has published two comprehensive series on maternal and child nutrition, in 2008[6] and 2013.[5] The series review the epidemiology of global malnutrition and analyze the state of the evidence for cost-effective interventions that should be scaled-up to achieve impact and global targets. In the first of such series,[6] investigators define the importance of the 1000 day and identify child malnutrition as being responsible for one third of all child deaths worldwide. This finding is key in that it points at malnutrition as a key determinant of child mortality that is often overlooked. When a child dies of pneumonia, malaria or diarrhea (some of the causes of child mortality in the world), it may well be that malnutrition is a key contributing factor that prevents the body from successfully fighting the infection and recovering from the disease.[6] In the follow up series in 2013,[5] the focus on undernutrition is expanded to the increasing burden of obesity in both high, middle and low income countries. Several countries with high levels of child stunting and undernutrition are starting to display worrisome increasing trends of child obesity concurrently, due to increased wealth and the persistence of significant inequalities.[5] The challenges these countries face are particularly difficult as they require intervening on two levels on what has come to be called “double burden of malnutrition”.[5] As an example, in India 30% of children under 5 years of age are stunted, and 20% are overweight. Neglecting these nutritional problems is not an option anymore if countries are to escape poverty traps and provide opportunities to their people to live fulfilling productive lives without stunting.[5]

Nutritional interventions such as dietary supplementation and nutritional education have the potential to decrease stunting.[27]

Examples

The 2012 World Health Assembly, with its 194 member states, convened to discuss global issues of maternal, infant and young child nutrition, and developed a plan with 6 targets for 2025.[4] The first of such targets aims to reduce by 40% the number of children who are stunted in the world, by 2025. This would correspond to 100 million stunted children in 2025. At the current reduction rate, the predicted number in 2025 will be 127 million, indicating the need to scale-up and intensify efforts if the global community is to reach its goals.[4]

The World Bank estimates that the extra cost to achieve the reduction goal will be $8.50 yearly per stunted child, for a total of $49.6 Billion for the next decade.[28] Stunting has been shown to be one of the most cost-effective global health problems to invest in, with an estimated return on investment of $18 for every dollar spent thanks to its impact on economic productivity.[28] Despite the evidence in favor of investing in the reduction of stunting, current investments are too low at about $2.9 billion per year, with $1.6 billion coming from Governments, $0.2 billion from donors, and $1.1 paid by individuals.[28]

Sustainable Development Goals

In 2015, the United Nations and its member states agreed on a new sustainable development agenda to promote prosperity and reduce poverty, putting forward 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030.[29] SDG 2 aims to “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture”. Sub-goal 2.2. aims to “by 2030 end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving by 2025 the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under five years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, and older persons”.

The global community has recognized more and more the critical importance of stunting during the past decade. Investments to address it have increased but remain far from being sufficient to solve it and unleash the human potential that remains trapped in malnutrition.

The "Scaling Up Nutrition Movement (SUN)" movement is the main network of governments, non-governmental and international organizations, donors, private companies and academic institutions working together in pursuit of improved global nutrition and a world without hunger and malnutrition.[30] It was launched at the UN General Assembly of 2010 and it calls for country-led multi-sectoral strategies to address child malnutrition by scaling-up evidence-based interventions in both nutrition specific and sensitive areas. As of 2016, 50 countries have joined the SUN Movement with strategies that are aligned with international frameworks of action.[30]

Brazil

Brazil displayed a remarkable reduction in the rates of child stunting under age 5, from 37% in 1974, to 7.1% in 2007.[4] This happened in association with impressive social and economic development that reduced the numbers of Brazilians living in extreme poverty (less than $1.25 per day) from 25.6% in 1990 to 4.8% in 2008.[4] The successful reduction in child malnutrition in Brazil can be attributed to strong political commitment that led to improvements in the water and sanitation system, increased female schooling, scale-up of quality maternal and child health services, increased economic power at family level (including successful cash transfer programs), and improvements in food security throughout the country.[4]

Peru

After a decade (1995–2005) in which stunting rates stagnated in the country, Peru designed and implemented a national strategy against child malnutrition called crecer ("grow"), which complemented a social development conditional cash-transfer program called juntos, which included a nutritional component.[4] The strategy was multisectoral in that it involved the health, education, water, sanitation and hygiene, agriculture and housing sectors and stakeholders.[4] It was led by the Government and the Prime Minister himself, and included non-governmental partners at both central, regional and community level. After the strategy was implemented, stunting went from 22.9% to 17.9% (2005–2010), with very significant improvements in rural areas where it had been more difficult to reduce stunting rates in the past.[4]

India

The State of Maharashtra in Central-Western India has been able to produce an impressive reduction in stunting rates in children under 2 years of age from 44% to 22.8% in the 2005–2012 period.[4] This is particularly remarkable given the immense challenges India has faced to address malnutrition, and that the country hosts almost half of all stunted children under 5 in the world.[4][15] This was achieved through integrated community-based programs that were designed by a central advisory body that promoted multisectoral collaboration, provided advice to policy-makers on evidence-based solutions, and advocated for the key role of the 1000 days (pregnancy and first two years of life).[4]

See also

- Compensatory growth

- Failure to thrive

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition

- Undernutrition in children

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLiS)". WHO. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ↑ United Nations Children's Fund, World Health Organization, The World Bank. UNICEFWHO- World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. (http://data.unicef.org/resources/2013/webapps/nutrition Archived 2018-09-07 at the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ Spears, D. (2013). How much international variation in child height can sanitation explain? - Policy research working paper Archived 2017-03-12 at the Wayback Machine. The World Bank, Sustainable Development Network, Water and Sanitation Program

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 "World Health Assembly Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Stunting Policy Brief, World Health Organization 2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 "Lancet series on maternal and child nutrition (2013)". Archived from the original on 2014-10-07. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 "Lancet series on maternal and child undernutrition (2008)". Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 A. Balalian, Arin; Simonyan, Hambardzum; Hekimian, Kim; Deckelbaum, Richard J.; Sargsyan, Aelita (December 2017). "Prevalence and determinants of stunting in a conflict-ridden border region in Armenia - a cross-sectional study". BMC Nutrition. 3: 85. doi:10.1186/s40795-017-0204-9. PMC 7050870. PMID 32153861.

- ↑ Caulfield, Laura E.; Huffman, Sandra L.; Piwoz, Ellen G. (January 1999). "Interventions to Improve Intake of Complementary Foods by Infants 6 to 12 Months of Age in Developing Countries: Impact on Growth and on the Prevalence of Malnutrition and Potential Contribution to Child Survival". Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 20 (2): 183–200. doi:10.1177/156482659902000203. ISSN 0379-5721.

- ↑ Issaka, Abukari I.; Agho, Kingsley E.; Page, Andrew N.; Burns, Penelope L.; Stevens, Garry J.; Dibley, Michael J. (October 2015). "Determinants of suboptimal complementary feeding practices among children aged 6-23 months in four anglophone West African countries: Complementary feeding in anglophone West Africa". Maternal & Child Nutrition. 11: 14–30. doi:10.1111/mcn.12194. PMC 6860259. PMID 26364789.

- ↑ Akombi, Blessing; Agho, Kingsley; Hall, John; Wali, Nidhi; Renzaho, Andre; Merom, Dafna (2017-08-01). "Stunting, Wasting and Underweight in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 14 (8): 863. doi:10.3390/ijerph14080863. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 5580567. PMID 28788108.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Akhtar, Saeed (2016-10-25). "Malnutrition in South Asia—A Critical Reappraisal". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 56 (14): 2320–2330. doi:10.1080/10408398.2013.832143. ISSN 1040-8398. PMID 25830938. S2CID 205691877.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Velleman, Y., Pugh, I. (2013). Under-nutrition and water, sanitation and hygiene - Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) play a fundamental role in improving nutritional outcomes. A successful global effort to tackle under-nutrition must include WASH. Archived 2016-04-02 at the Wayback Machine Briefing Note by WaterAid and Share, UK

- ↑ Cumming O, Cairncross S. Can water, sanitation and hygiene help eliminate stunting? Current evidence and policy implications Archived 2021-12-13 at the Wayback Machine. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):91-105. doi:10.1111/mcn.12258

- ↑ Ngure, F.M.; Reid, B.; Humphrey, J.; Mbuya, M.; Pelto, G. and Stoltzfus, R. (2017) ‘Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH), Environmental Enteropathy, Nutrition, and Early Child Development: Making the Links’, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1308: 118-128

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Chambers, R. and von Medeazza, G. (2014) Reframing Undernutrition: Faecally-Transmitted Infections and the 5 As Archived 2021-12-13 at the Wayback Machine, IDS Working Paper 450, Brighton: IDS

- ↑ Budge S, Parker AH, Hutchings PT, Garbutt C. Environmental enteric dysfunction and child stunting Archived 2021-12-13 at the Wayback Machine. Nutr Rev. 2019 Apr 1;77(4):240-253. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuy068. PMID: 30753710; PMCID: PMC6394759.

- ↑ Walker, Christa L Fischer; Rudan, Igor; Liu, Li; Nair, Harish; Theodoratou, Evropi; Bhutta, Zulfiqar A; O'Brien, Katherine L; Campbell, Harry; Black, Robert E (April 2013). "Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea". The Lancet. 381 (9875): 1405–1416. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6. PMC 7159282. PMID 23582727.

- ↑ "The Lancet series on Maternal and Child Nutrition". The Lancet. 6 June 2013. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ↑ Humphrey, JH (19 September 2009). "Child undernutrition, tropical enteropathy, toilets, and handwashing". Lancet. 374 (9694): 1032–5. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60950-8. PMID 19766883. S2CID 13851530. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Smith, L. and Haddad, L. (2014) Reducing Child Undernutrition: Past Drivers and Priorities for the Post-MDG Era Archived 2017-04-18 at the Wayback Machine, IDS Working Paper 441, IDS (Institute for Development Studies), UK

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Franck Flachenberg, Regine Kopplow (2014) How to better link WASH and nutrition programmes Archived 2015-12-28 at the Wayback Machine, Concern Worldwide Technical Briefing Note

- ↑ Lake, Anthony (2017-01-14). "The first 1,000 days of a child's life are the most important to their development - and our economic success". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 UNICEF (2013). Improving child nutrition : the achievable imperative for global progress. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), New York, USA. ISBN 978-92-806-4686-3. Archived from the original on 2013-05-13. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- ↑ 24.00 24.01 24.02 24.03 24.04 24.05 24.06 24.07 24.08 24.09 24.10 24.11 24.12 24.13 24.14 24.15 "Levels and trends in child malnutrition, UNICEF 2016" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-16. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- ↑ Local Burden of Disease Child Growth Failure Collaborators (January 2020). "Mapping child growth failure across low- and middle-income countries". Nature. 577 (7789): 231–234. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..231L. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1878-8. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 7015855. PMID 31915393.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Maria Quattri, Susanna Smets, and Viengsompasong Inthavong (2014) Investing in the Next Generation - Children grow taller, and smarter, in rural, mountainous villages of Lao PDR where all community members use improved sanitation Archived 2022-01-19 at the Wayback Machine, WSP (Water and Sanitation Program), World Bank, USA

- ↑ Goudet SM, Bogin BA, Madise NJ, Griffiths PL (2019). "Nutritional Interventions for Preventing Stunting in Children (Birth to 59 Months) Living in Urban Slums in Low- And Middle-Income Countries (LMIC)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD011695. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011695.pub2. PMC 6572871. PMID 31204795.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 "World Bank Costing Analysis for Stunting Targets (2015)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-11-07. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- ↑ "United Nations Sustainable Development Goals". Archived from the original on 2018-01-06. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Scaling Up Nutrition Movement website". Archived from the original on 2018-06-22. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Stop stunting Archived 2021-12-07 at the Wayback Machine, regional conference on nutrition in South Asia (website slow to load)

- Alive and Thrive Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, program website

- Visualizing child growth failure from 2000-2017 Archived 2022-01-27 at the Wayback Machine, interactive visualization