Sex cord–gonadal stromal tumour

| Sex cord–gonadal stromal tumor | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Sex cord–stromal tumour,[1] sex cord tumor[2] | |

| |

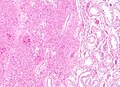

| Micrograph of a granulosa cell tumour, a type of sex-cord–gonadal stromal tumour. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Oncology, gynecology, urology |

| Symptoms | Females Adnexal mass, abdominal bloating, male pattern hair growth, menstrual changes[3]: Males: Painless testicular mass[4] |

| Complications | Ovarian torsion[3] |

| Usual onset | Variable[3][5] |

| Types | Granulosa, sertoli cell, sex cord tumor with annular tubules, gynandroblastoma, steroid cell, Leydig cell[2][1] |

| Diagnostic method | Supported by medical imaging and blood tests, confirmed by microscopic examination[6][7][5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Other ovarian or testicular tumors[1][5] |

| Treatment | Surgery[3][5] |

| Frequency | ~5% of ovarian and testicular tumors[3][5] |

Sex cord–gonadal stromal tumors are a group of tumors derived from the stroma or sex cord of the ovary or testis.[6][2] They may be benign or cancerous.[6] In women, symptoms may include adnexal mass, abdominal bloating, male pattern hair growth, and menstrual changes.[3] Complications may include ovarian torsion.[3] In males symptoms typically include a painless testicular mass.[4]

Types include granulosa tumors, sertoli cell tumors, sex cord tumor with annular tubules, gynandroblastoma, steroid cell tumors, and Leydig cell tumors.[2][1] Diagnosis may be supported by medical imaging and blood tests and confirmed by microscopic examination.[6][7][5] They are in contrast, to surface epithelial-stromal tumors which arise from the lining around the gonads and germ cell tumors which arise from the precursor cells of the gametes.[1]

Treatment is generally by surgery.[3][5] This group accounts for 5% of ovarian tumors and 5% of testicular cancers.[3][5] Different types present at different ages.[3][5] In females surface epithelial-stromal tumors are more common and in males germ cell tumors are more common.[8][5]

Types

These tumours are of the following types, characterized by their abnormal production of otherwise apparently normal cells or tissues.

| Classification of sex cord–gonadal stromal tumours by their histology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell/tissue normal location | ||||

| Ovary (female) | Testicle (male) | Mixed | ||

| Cell/tissue type | Sex cord | Granulosa cell tumour | Sertoli cell tumour | Gynandroblastoma |

| Gonadal stroma | Thecoma, Fibroma | Leydig cell tumour | Gynandroblastoma | |

| Mixed | Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour | Gynandroblastoma | ||

Although each of the cell and tissue types normally occurs in just one sex (male or female), within a tumour they can occur in the opposite sex. Consequently, depending on the specific histology produced, these tumours can cause virilization in women and feminization in men.

By prevalence

- Granulosa cell tumour. This tumour produces granulosa cells, which normally are found in the ovary. It is malignant in 20% of women diagnosed with it. It tends to present in women in the 50-55yo age group with post menopausal vaginal bleeding. Uncommonly, a similar but possibly distinct tumour, juvenile granulosa cell tumour, presents in pre-pubertal girls with precocious puberty. In both groups, the vaginal bleeding is due to oestrogen secreted by the tumour. In older women, treatment is total abdominal hysterectomy and removal of both ovaries. In young girls, fertility sparing treatment is the mainstay for non-metastatic disease.

- Sertoli cell tumour. This tumour produces Sertoli cells, which normally are found in the testicle. This tumour occurs in both men and women.

- Thecoma. This tumour produces theca of follicle, a tissue normally found in the ovarian follicle. The tumour is almost exclusively benign and unilateral. It typically secretes estrogen, and as a result women with this tumour often present with postmenopausal bleeding.

- Leydig cell tumour. This tumour produces Leydig cells, which normally are found in the testicle and tend to secrete androgens.

- Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour. This tumour produces both Sertoli and Leydig cells. Although both cell types normally occur in the testicle, this tumour can occur in the ovary.

- Gynandroblastoma. A very rare tumour producing both ovarian (granulosa and/or theca) and testicular (Sertoli and/or Leydig) cells or tissues. Typically it consists of adult-type granulosa cells and Sertoli cells,[10][11] but it has been reported with juvenile-type granulosa cells.[12] It has been reported to occur in the ovary usually, rarely in the testis.[13] Due to its rarity, the malignant potential of this tumour is unclear; there is one case report of late metastasis.

- Sex cord tumour with annular tubules (SCTAT) These are rare tumours that may be sporadic or associated with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of these tumours is based on the histology of tissue obtained in a biopsy or surgical resection. In a retrospective study of 72 cases in children and adolescents, the histology was important to prognosis.[14]

A number of molecules have been proposed as markers for this group of tumours. CD56 may be useful for distinguishing sex cord–stromal tumours from some other types of tumours, although it does not distinguish them from neuroendocrine tumours.[15] Calretinin has also been suggested as a marker.[16] For diagnosis of granulosa cell tumour, inhibin is under investigation.[citation needed] Granulosa cell tumors and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors have specific genetic mutations that are characteristic and can help support the diagnosis.

On magnetic resonance imaging, a fibroma may produce one of several imaging features that might be used in the future to identify this rare tumour prior to surgery.[17][18]

-

Low magnification micrograph of a granulosa cell tumour. H&E stain.

-

High magnification micrograph of a thecoma. H&E stain.

-

Low magnification micrograph of a thecoma. H&E stain.

-

Low magnification micrograph of a Leydig cell tumour. H&E stain.

-

Intermediate magnification micrograph of a Leydig cell tumour. H&E stain.

-

High magnification micrograph of a Leydig cell tumour. H&E stain.

-

Low magnification micrograph of a Sertoli cell tumour. H&E stain.

-

High magnification micrograph of a Sertoli cell tumour. H&E stain.

Prognosis

A retrospective study of 83 women with sex cord–stromal tumours (73 with granulosa cell tumour and 10 with Sertoli-Leydig cell tumour), all diagnosed between 1975 and 2003, reported that survival was higher with age under 50, smaller tumour size, and absence of residual disease. The study found no effect of chemotherapy.[19] A retrospective study of 67 children and adolescents reported some benefit of cisplatin-based chemotherapy.[20]

Research

A prospective study of ovarian sex cord–stromal tumours in children and adolescents began enrolling participants in 2005.[20] The International Ovarian and Testicular Stromal Tumor Registry is studying these rare tumors and collecting data on them to further research. Targeted treatments are being evaluated for these tumors as well.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "WHO classification". www.pathologyoutlines.com. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/sex-cord-stromal-tumor". www.cancer.gov. 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Schultz, KA; Harris, AK; Schneider, DT; Young, RH; Brown, J; Gershenson, DM; Dehner, LP; Hill, DA; Messinger, YH; Frazier, AL (October 2016). "Ovarian Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors". Journal of oncology practice. 12 (10): 940–946. doi:10.1200/JOP.2016.016261. PMID 27858560.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Orphanet: Sex cord stromal tumor of testis". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Kapoor, M; Budh, DP (January 2020). "Sex Cord Stromal Testicular Tumor". PMID 32644342.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Sex cord stromal ovarian tumours | Ovarian cancer | Cancer Research UK". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Orphanet: Malignant sex cord stromal tumor of ovary". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2021. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Orph2021" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Saba, Luca; Acharya, U. Rajendra; Guerriero, Stefano; Suri, Jasjit S. (2014). Ovarian Neoplasm Imaging. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-4614-8633-6. Archived from the original on 2021-07-10. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ↑ - Vaidya, SA; Kc, S; Sharma, P; Vaidya, S (2014). "Spectrum of ovarian tumors in a referral hospital in Nepal". Journal of Pathology of Nepal. 4 (7): 539–543. doi:10.3126/jpn.v4i7.10295. ISSN 2091-0908.

- Minor adjustment for mature cystic teratomas (0.17 to 2% risk of ovarian cancer): Mandal, Shramana; Badhe, Bhawana A. (2012). "Malignant Transformation in a Mature Teratoma with Metastatic Deposits in the Omentum: A Case Report". Case Reports in Pathology. 2012: 1–3. doi:10.1155/2012/568062. ISSN 2090-6781. - ↑ Chivukula, Mamatha; Hunt, Jennifer; Carter, Gloria; Kelley, Joseph; Patel, Minita; Kanbour-Shakir, Amal (2007). "Recurrent Gynandroblastoma of Ovary-A Case Report". International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 26 (1): 30–3. doi:10.1097/01.pgp.0000225387.48868.39. PMID 17197894.

- ↑ Limaïem, F; Lahmar, A; Ben Fadhel, C; Bouraoui, S; M'zabi-Regaya, S (2008). "Gynandroblastoma. Report of an unusual ovarian tumour and literature review". Pathologica. 100 (1): 13–7. PMID 18686520.

- ↑ Broshears, John R.; Roth, Lawrence M. (1997). "Gynandroblastoma with Elements Resembling Juvenile Granulosa Cell Tumor". International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 16 (4): 387–91. doi:10.1097/00004347-199710000-00016. PMID 9421080.

- ↑ Antunes, L; Ounnoughene-Piet, M; Hennequin, V; Maury, F; Lemelle, J-L; Labouyrie, E; Plenat, F (2002). "Gynandroblastoma of the testis in an infant: a morphological, immunohistochemical and in-situ hybridization report". Histopathology. 40 (4): 395–7. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.t01-2-01299.x. PMID 11943029.

- ↑ Schneider, Dominik T.; Jänig, Ute; Calaminus, Gabriele; Göbel, Ulrich; Harms, Dieter (2003). "Ovarian sex cord–stromal tumors—a clinicopathological study of 72 cases from the Kiel Pediatric Tumor Registry". Virchows Archiv. 443 (4): 549–60. doi:10.1007/s00428-003-0869-0. PMID 12910419.

- ↑ McCluggage, W. Glenn; McKenna, Michael; McBride, Hilary A. (2007). "CD56 is a Sensitive and Diagnostically Useful Immunohistochemical Marker of Ovarian Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors". International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 26 (3): 322–7. doi:10.1097/01.pgp.0000236947.59463.87. PMID 17581419.

- ↑ Deavers, Michael T.; Malpica, Anais; Liu, Jinsong; Broaddus, Russell; Silva, Elvio G. (2003). "Ovarian Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors: an Immunohistochemical Study Including a Comparison of Calretinin and Inhibin". Modern Pathology. 16 (6): 584–90. doi:10.1097/01.MP.0000073133.79591.A1. PMID 12808064.

- ↑ Takeuchi, Mayumi; Matsuzaki, Kenji; Sano, Nobuya; Furumoto, Hiroyuki; Nishitani, Hiromu (2008). "Ovarian Fibromatosis". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 32 (5): 776–7. doi:10.1097/RCT.0b013e318157689a. PMID 18830110.

- ↑ Kitajima, Kazuhiro; Kaji, Yasushi; Sugimura, Kazuro (2008). "Usual and Unusual MRI Findings of Ovarian Fibroma: Correlation with Pathologic Findings". Magnetic Resonance in Medical Sciences. 7 (1): 43–8. doi:10.2463/mrms.7.43. PMID 18460848.

- ↑ Chan, J; Zhang, M; Kaleb, V; Loizzi, V; Benjamin, J; Vasilev, S; Osann, K; Disaia, P (2005). "Prognostic factors responsible for survival in sex cord stromal tumors of the ovary?A multivariate analysis". Gynecologic Oncology. 96 (1): 204–9. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.019. PMID 15589602.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Schneider, DT; Calaminus, G; Harms, D; Göbel, U; German Maligne Keimzelltumoren Study Group (2005). "Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors in children and adolescents". The Journal of reproductive medicine. 50 (6): 439–46. PMID 16050568.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Pages with script errors

- Pages with reference errors

- CS1 errors: external links

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2009

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Gynaecological cancer

- Male genital neoplasia

- Ovarian cancer

- RTT