Rosacea

| Rosacea | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Acne rosacea | |

| |

| Rosacea over the cheeks and nose[1] | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Facial redness, pimples, swelling, and small and superficial dilated blood vessels[2][3] |

| Complications | Rhinophyma[3] |

| Usual onset | 30–50 years old[2] |

| Duration | Long term[2] |

| Types | Erythematotelengiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, ocular[2] |

| Causes | Unknown[2] |

| Risk factors | Family history[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Acne, perioral dermatitis, seborrhoeic dermatitis, dermatomyositis, lupus[2] |

| Medication | Antibiotics either by mouth or applied to the skin[3] |

| Frequency | ~5%[2] |

Rosacea is a long-term skin condition that typically affects the face.[2][3] It results in redness, pimples, swelling, and small and superficial dilated blood vessels.[2] Often, the nose, cheeks, forehead, and chin are most involved.[3] A red, enlarged nose may occur in severe disease, a condition known as rhinophyma.[3]

The cause of rosacea is unknown.[2] Risk factors are believed to include a family history of the condition.[3] Factors that may potentially worsen the condition include heat, exercise, sunlight, cold, spicy food, alcohol, menopause, psychological stress, or steroid cream on the face.[3] Diagnosis is based on symptoms.[2]

While not curable, treatment usually improves symptoms.[3] Treatment is typically with metronidazole, doxycycline, minocycline, or tetracycline.[4] When the eyes are affected, azithromycin eye drops may help.[5] Other treatments with tentative benefit include brimonidine cream, ivermectin cream, and isotretinoin.[4] Dermabrasion or laser surgery may also be used.[3] The use of sunscreen is typically recommended.[3]

Rosacea affects between 1 and 10% of people.[2] Those affected are most often 30 to 50 years old and female.[2] Caucasians are more frequently affected.[2] The condition was described in The Canterbury Tales in the 1300s, and possibly as early as the 200s BC by Theocritus.[6][7]

Signs and symptoms

Signs include facial redness, small and superficial dilated blood vessels on facial skin, papules, pustules, and swelling.[2]

Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea

Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea[8] rosacea (also known as "vascular rosacea"[8]) is characterized by prominent history of prolonged (over 10 minutes) flushing reaction to various stimuli, such as emotional stress, hot drinks, alcohol, spicy foods, exercise, cold or hot weather, or hot baths and showers.[9]

Glandular rosacea

In glandular rosacea, men with thick sebaceous skin predominate, a disease in which the papules are edematous, and the pustules are often 0.5 to 1.0 cm in size, with nodulocystic lesions often present.[9]

-

Rosacea on the face

-

Rosacea

-

Rosacea

-

Rosacea

Cause

The exact cause of rosacea is unknown.[2] Triggers that cause episodes of flushing and blushing play a part in its development. Exposure to temperature extremes, strenuous exercise, heat from sunlight, severe sunburn, stress, anxiety, cold wind, and moving to a warm or hot environment from a cold one, such as heated shops and offices during the winter, can each cause the face to become flushed.[2] Certain foods and drinks can also trigger flushing, such as alcohol, foods and beverages containing caffeine (especially hot tea and coffee), foods high in histamines, and spicy foods.[10]

Medications and topical irritants have also been known to trigger rosacea flares. Some acne and wrinkle treatments reported to cause rosacea include microdermabrasion and chemical peels, as well as high dosages of isotretinoin, benzoyl peroxide, and tretinoin.

Steroid-induced rosacea is caused by the use of topical steroids.[11] These steroids are often prescribed for seborrheic dermatitis. Dosage should be slowly decreased and not immediately stopped to avoid a flare-up.

Cathelicidins

In 2007, Richard Gallo and colleagues noticed that patients with rosacea had high levels of the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin[12] and elevated levels of stratum corneum tryptic enzymes (SCTEs). Antibiotics have been used in the past to treat rosacea, but they may only work because they inhibit some SCTEs.[12]

Demodex mites

Studies of rosacea and Demodex mites have revealed that some people with rosacea have increased numbers of the mite,[10] especially those with steroid-induced rosacea. On other occasions, demodicidosis (commonly known as "mange") is a separate condition that may have "rosacea-like" appearances.[13]

A 2007, National Rosacea Society-funded study demonstrated that Demodex folliculorum mites may be a cause or exacerbating factor in rosacea.[14] The researchers identified Bacillus oleronius as distinct bacteria associated with Demodex mites. When analyzing blood samples using a peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferation assay, they discovered that B. oleronius stimulated an immune system response in 79 percent of 22 patients with subtype 2 (papulopustular) rosacea, compared with only 29% of 17 subjects without the disorder. They concluded, "The immune response results in inflammation, as evident in the papules (bumps) and pustules (pimples) of subtype 2 rosacea. This suggests that the B. oleronius bacteria found in the mites could be responsible for the inflammation associated with the condition."[14]

Intestinal bacteria

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) was demonstrated to have greater prevalence in rosacea patients and treating it with locally acting antibiotics led to rosacea lesion improvement in two studies. Conversely in rosacea patients who were SIBO negative, antibiotic therapy had no effect.[15] The effectiveness of treating SIBO in rosacea patients may suggest that gut bacteria play a role in the pathogenesis of rosacea lesions.

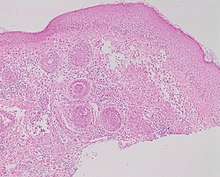

Diagnosis

Most people with rosacea have only mild redness and are never formally diagnosed or treated. No test for rosacea is known. In many cases, simple visual inspection by a trained health-care professional is sufficient for diagnosis. In other cases, particularly when pimples or redness on less-common parts of the face is present, a trial of common treatments is useful for confirming a suspected diagnosis. The disorder can be confused or co-exist with acne vulgaris or seborrheic dermatitis. The presence of a rash on the scalp or ears suggests a different or co-existing diagnosis because rosacea is primarily a facial diagnosis, although it may occasionally appear in these other areas.

Classification

Four rosacea subtypes exist,[18] and a patient may have more than one subtype:[19]: 176

- Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea exhibits permanent redness (erythema) with a tendency to flush and blush easily.[10] Also small, widened blood vessels visible near the surface of the skin (telangiectasias) and possibly intense burning, stinging, and itching are common.[10] People with this type often have sensitive skin. Skin can also become very dry and flaky. In addition to the face, signs can also appear on the ears, neck, chest, upper back, and scalp.[20]

- Papulopustular rosacea presents with some permanent redness with red bumps (papules); some pus-filled pustules can last 1–4 days or longer. This subtype is often confused with acne.

- Phymatous rosacea is most commonly associated with rhinophyma, an enlargement of the nose. Signs include thickening skin, irregular surface nodularities, and enlargement. Phymatous rosacea can also affect the chin (gnathophyma), forehead (metophyma), cheeks, eyelids (blepharophyma), and ears (otophyma).[21] Telangiectasias may be present.

- In ocular rosacea, affected eyes and eyelids may appear red due to telangiectasias and inflammation, and may feel dry, irritated, or gritty. Other symptoms include foreign-body sensations, itching, burning, stinging, and sensitivity to light.[22] Eyes can become more susceptible to infection. About half of the people with subtypes 1–3 also have eye symptoms. Blurry vision and vision loss can occur if the cornea is affected.[22]

Variants

Variants of rosacea include:[23]: 689

- Pyoderma faciale, also known as rosacea fulminans,[23] is a conglobate, nodular disease that arises abruptly on the face.[8][23]

- Rosacea conglobata is a severe rosacea that can mimic acne conglobata, with hemorrhagic nodular abscesses and indurated plaques.[23]

- Phymatous rosacea is a cutaneous condition characterized by overgrowth of sebaceous glands.[8] Phyma is Greek for swelling, mass, or bulb, and these can occur on the face and ears.[23]: 693

Treatments

Treatment of depends on the types present.[24] Mild cases are often not treated at all, or are simply covered up with normal cosmetics.

Therapy for the treatment of rosacea is not curative, and is best measured in terms of reduction in the amount of facial redness and inflammatory lesions, a decrease in the number, duration, and intensity of flares, and concomitant symptoms of itching, burning, and tenderness. The two primary modalities of rosacea treatment are topical and oral antibiotic agents.[25] Laser therapy has also been classified as a form of treatment.[25] While medications often produce a temporary remission of redness within a few weeks, the redness typically returns shortly after treatment is suspended. Long-term treatment, usually 1–2 years, may result in permanent control of the condition for some patients.[25][26] Lifelong treatment is often necessary, although some cases resolve after a while and go into a permanent remission.[26] Other cases, if left untreated, worsen over time.[citation needed]

Behavior

Avoiding triggers that worsen the condition can help reduce the onset of rosacea, but alone will not normally lead to remission except in mild cases. Keeping a journal is sometimes recommended to help identify and reduce food and beverage triggers.

Because sunlight is a common trigger, avoiding excessive exposure to the sun is widely recommended. Some people with rosacea benefit from daily use of a sunscreen; others opt for wearing hats with broad brims. Like sunlight, emotional stress can also trigger rosacea. People who develop infections of the eyelids must practice frequent eyelid hygiene.

Managing pretrigger events such as prolonged exposure to cool environments can directly influence warm-room flushing.[27]

Medications

Medications with good evidence include topical ivermectin, azelaic acid, brimonidine, and doxycycline and isotretinoin by mouth.[28] Lesser evidence supports topical metronidazole and tetracycline by mouth.[28] Benefits occur in 65 to 75% of people.[29]

Metronidazole is thought to act through anti-inflammatory mechanisms, while azelaic acid is thought to decrease cathelicidin production. Oral antibiotics of the tetracycline class such as doxycycline, minocycline, and oxytetracycline are also commonly used and thought to reduce papulopustular lesions through anti-inflammatory actions rather than through their antibacterial capabilities.[10]

Using alpha-hydroxy acid peels may help relieve redness caused by irritation, and reduce papules and pustules associated with rosacea.[30] Oral antibiotics may help to relieve symptoms of ocular rosacea. If papules and pustules persist, then sometimes isotretinoin can be prescribed.[31] The flushing and blushing that typically accompany rosacea are typically treated with the topical application of alpha agonists such as brimonidine and less commonly oxymetazoline or xylometazoline.[10]

Laser

Evidence for the use of laser and intense pulsed-light therapy in rosacea is poor.[32]

Epidemiology

Women, especially those who are menopausal, are more likely than men to develop rosacea.[33] Those of Caucasian descent, especially those of Northern or Eastern European descent, appear more affected.[34]

See also

References

- ↑ Sand, M; Sand, D; Thrandorf, C; Paech, V; Altmeyer, P; Bechara, FG (4 June 2010). "Cutaneous lesions of the nose". Head & Face Medicine. 6: 7. doi:10.1186/1746-160X-6-7. PMC 2903548. PMID 20525327.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 Tüzün Y, Wolf R, Kutlubay Z, Karakuş O, Engin B (February 2014). "Rosacea and rhinophyma". Clinics in Dermatology. 32 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.05.024. PMID 24314376.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 "Questions and Answers about Rosacea". www.niams.nih.gov. April 2016. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 van Zuuren, EJ; Fedorowicz, Z (September 2015). "Interventions for rosacea: abridged updated Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments". The British Journal of Dermatology. 173 (3): 651–62. doi:10.1111/bjd.13956. PMID 26099423.

- ↑ "Rosacea First choice treatments". Prescrire International. 182: 126–128. May 2017. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Zouboulis, Christos C.; Katsambas, Andreas D.; Kligman, Albert M. (2014). Pathogenesis and Treatment of Acne and Rosacea. Springer. p. XXV. ISBN 978-3-540-69375-8. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Schachner, Lawrence A.; Hansen, Ronald C. (2011). Pediatric Dermatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 827. ISBN 978-0-7234-3665-2. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. Page 245. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Del Rosso JQ (October 2014). "Management of cutaneous rosacea: emphasis on new medical therapies". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 15 (14): 2029–38. doi:10.1517/14656566.2014.945423. PMID 25186025. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ↑ "Rosacea". DermNet, New Zealand Dermatological Society. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Kenshi Yamasaki; Anna Di Nardo; Antonella Bardan; Masamoto Murakami; Takaaki Ohtake; Alvin Coda; Robert A Dorschner; Chrystelle Bonnart; Pascal Descargues; Alain Hovnanian; Vera B Morhenn; Richard L Gallo (August 2007). "Increased serine protease activity and cathelicidin promotes skin inflammation in rosacea". Nature Medicine. 13 (8): 975–80. doi:10.1038/nm1616. PMID 17676051.

- ↑ Baima B, Sticherling M (2002). "Demodicidosis revisited". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 82 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1080/000155502753600795. PMID 12013194.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Lacey N, Delaney S, Kavanagh K, Powell FC (2007). "Mite-related bacterial antigens stimulate inflammatory cells in rosacea" (PDF). British Journal of Dermatology. 157 (3): 474–481. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08028.x. PMID 17596156. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ↑ Elizabeth Lazaridou; Christina Giannopoulou; Christina Fotiadou; Eustratios Vakirlis; Anastasia Trigoni; Demetris Ioannides (November 2010). "The potential role of microorganisms in the development of rosacea". JDDG: Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft. 9 (1): 21–25. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07513.x. PMID 21059171.

- ↑ name="JAmAcadDermatol2004-Wilkin">Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, Drake L, Liang MH, Odom R, Powell F (2004). "Standard grading system for rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea" (PDF). J Am Acad Dermatol. 50 (6): 907–12. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.048. PMID 15153893. Archived from the original (PDF reprint) on 27 February 2007.

- ↑ Celiker, Hande; Toker, Ebru; Ergun, Tulin; Cinel, Leyla (2017). "An unusual presentation of ocular rosacea". Arquivos Brasileiros de Oftalmologia. 80 (6): 396–398. doi:10.5935/0004-2749.20170097. ISSN 0004-2749. PMID 29267579.

- ↑ Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, Drake L, Liang MH, Odom R, Powell F (2004). "Standard grading system for rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea" (PDF). J Am Acad Dermatol. 50 (6): 907–12. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.048. PMID 15153893. Archived from the original (PDF reprint) on 27 February 2007.

- ↑ Marks, James G; Miller, Jeffery (2006). Lookingbill and Marks' Principles of Dermatology (4th ed.). Elsevier Inc. ISBN 1-4160-3185-5.

- ↑ "What Rosacea Looks Like". Archived from the original on 4 February 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Jansen T, Plewig G (1998). "Clinical and histological variants of rhinophyma, including nonsurgical treatment modalities". Facial Plast Surg. 14 (4): 241–53. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1064456. PMID 11816064.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Vieira AC, Mannis MJ (December 2013). "Ocular rosacea: common and commonly missed". J Am Acad Dermatol. 69 (6 (Suppl 1)): S36–41. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.04.042. PMID 24229635.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ↑ van Zuuren, EJ; Fedorowicz, Z; Tan, J; van der Linden, MMD; Arents, BWM; Carter, B; Charland, L (July 2019). "Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments". The British Journal of Dermatology. 181 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1111/bjd.17590. PMC 6850438. PMID 30585305.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Noah Scheinfeld; Thomas Berk (January 2010). "A Review of the Diagnosis and Treatment of Rosacea". Postgraduate Medicine. 122 (1): 139–43. doi:10.3810/pgm.2010.01.2107. PMID 20107297. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Culp B, Scheinfeld N (January 2009). "Rosacea: a review". P&T. 34 (1): 38–45. PMC 2700634. PMID 19562004.

- ↑ Dahl, Colin (2008). A Practical Understanding of Rosacea – part one. Australian Sciences. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 van Zuuren, EJ; Fedorowicz, Z; Carter, B; van der Linden, MM; Charland, L (28 April 2015). "Interventions for rosacea". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD003262. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003262.pub5. PMC 6481562. PMID 25919144.

- ↑ Ton, Joey (6 August 2019). "#241 "Who's the fairest of them all?": Topical treatments for rosacea". CFPCLearn. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ Tung, RC; Bergfeld, WF; Vidimos, AT; Remzi, BK (2000). "alpha-Hydroxy acid-based cosmetic procedures. Guidelines for patient management". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 1 (2): 81–8. doi:10.2165/00128071-200001020-00002. PMID 11702315.

- ↑ Hoting E, Paul E, Plewig G (December 1986). "Treatment of rosacea with isotretinoin". Int J Dermatol. 25 (10): 660–3. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1986.tb04533.x. PMID 2948928.

- ↑ van Zuuren, EJ; Fedorowicz, Z; Carter, B; van der Linden, MM; Charland, L (28 April 2015). "Interventions for rosacea". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003262. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003262.pub5. PMC 6481562. PMID 25919144.

- ↑ Tamparo, Carol (2011). Fifth Edition: Diseases of the Human Body. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-8036-2505-1.

- ↑ "Understanding Rosacea". Rosacea.org. 21 August 2012. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Rosacea |

- Rosacea at Curlie

- Rosacea photo library at Dermnet Archived 26 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Questions and Answers about Rosacea Archived 21 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, from the US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- Pages with script errors

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Use dmy dates from December 2017

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Use American English from December 2017

- All Wikipedia articles written in American English

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2016

- Articles with Curlie links

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Acneiform eruptions

- Erythemas

- Cutaneous conditions

- Dermatology task force articles

- RTT

- RTTEM