Rasagiline

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Azilect, Azipron, others |

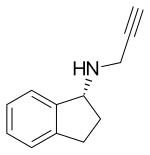

| Other names | VP-1012, N-propargyl-1(R)-aminoindan[1] |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Monoamine oxidase-B inhibitor[2] |

| Main uses | Parkinson's disease[2] |

| Side effects | Joint pain, indigestion, depression, trouble sleeping, swelling, nausea[3] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Typical dose | 1 mg OD[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a606017 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 36% |

| Protein binding | 88 – 94% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP1A2-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 3 hours[citation needed] |

| Excretion | Kidney and fecal |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H13N |

| Molar mass | 171.243 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Rasagiline, sold under the brand name Azilect among others, is a medication used to treat symptoms in Parkinson's disease.[2] It may be used alone or together with other medication.[2] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include joint pain, indigestion, depression, trouble sleeping, swelling, and nausea.[3] Other side effects may include high blood pressure, serotonin syndrome, sleepiness, compulsive gambling, and hallucinations.[3] Safety in pregnancy and breastfeeding is unclear.[5] It is an irreversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase-B.[2]

Rasagiline was developed in the early 1979 and approved for medical use in Europe in 2005 and the United States in 2006.[6][2][7] It is available as a generic medication.[4] In the United Kingdom 4 weeks of medication costs the NHS about £2.50.[4]

Medical use

Rasagiline is used to treat symptoms of Parkinson's disease both alone and in combination with other drugs. It has shown efficacy in both early and advanced Parkinsons, and appears to be especially useful in dealing with non-motor symptoms like fatigue.[8][9][10] This amount in the United States costs about 50 USD.[11]

Dosage

It is taken at a dose of 1 mg per day.[4]

Side effects

The FDA label contains warnings that rasagiline may cause severe hypertension or hypotension, may make people sleepy, may make motor control worse in some people, may cause hallucinations and psychotic-like behavior, may cause impulse control disorder, may increase the risk of melanoma, and upon withdrawal may cause high fever or confusion.[10]

Side effects when the drug is taken alone include flu-like symptoms, joint pain, depression, stomach upset, headache, dizziness, and insomnia. When taken with L-DOPA, side effects include increased movement problems, accidental injury, sudden drops in blood pressure, joint pain and swelling, dry mouth, rash, abnormal dreams and digestive problems including vomiting, loss of appetite, weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea, constipation.[10] When taken with Parkinson's drugs other than L-DOPA, side effects include peripheral edema, fall, joint pain, cough, and insomnia.[10]

Pregnancy

Rasagiline has not been tested in pregnant women and is Pregnancy Category C in the US.[10]

Interactions

People who are taking meperidine, tramadol, methadone, propoxyphene, dextromethorphan, St. John’s wort, cyclobenzaprine, or another MAO inhibitor should not take rasagiline.[10]

The FDA drug label carries a warning of the risk of serotonin syndrome when rasagiline is used with antidepressants or with meperidine.[10] However the risk appears to be low, based on a multicenter retrospective study in 1504 people, which looked for serotonin syndrome in people with PD who were treated with rasagiline plus antidepressants, rasagiline without antidepressants, or antidepressants plus Parkinson's drugs other than either rasagiline or selegiline; no cases were identified.[8]

There is a risk of psychosis or bizarre behavior if rasagiline is used with dextromethorphan and there is a risk of non-selective MAO inhibition and hypertensive crisis if rasagiline is used with other MAO inhibitors.[10]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Parkinson's disease is characterized by the death of cells that produce dopamine, a neurotransmitter. An enzyme called monoamine oxidase (MAO) breaks down neurotransmitters. MAO has two forms, MAO-A and MAO-B. MAO-B breaks down dopamine. Rasagiline prevents the breakdown of dopamine by irreversibly binding to MAO-B. Dopamine is therefore more available, somewhat compensating for the diminished quantities made in the brains of people with Parkinson's.[8]

Selegiline was the first selective MAO-B inhibitor. It is partly metabolized to levomethamphetamine (l-methamphetamine), one of the two enantiomers of methamphetamine, in vivo.[12][13] While these metabolites may contribute to selegiline's ability to inhibit reuptake of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine, they have also been associated with orthostatic hypotension and hallucinations in some people.[13][14][15] Rasagiline metabolizes into 1(R)-aminoindan which has no amphetamine-like characteristics[16] and has neuroprotective properties in cells and in animal models.[17]

It is selective for MAO type B over type A by a factor of fourteen.[18]

Metabolism

Rasagiline is broken down via CYP1A2,[19] part of the cytochrome P450 metabolic path in the liver. It is contraindicated in patients with hepatic insufficiency and its use should be monitored carefully in patients taking other drugs that alter the normal effectiveness of this metabolic path.[10]

Chemistry

Rasagiline is molecularly a propargylamine derivative.[20] The form brought to market by Teva and its partners is the mesylate salt, and was designated chemically as: 1H-Inden-1-amine-2,3-dihydro-N-2-propynyl-(1R)-methanesulfonate.[10]

History

Racemic rasagiline was discovered and patented by Aspro Nicholas in the 1970s as a drug candidate for treatment of hypertension.[21]

Moussa Youdim, a biochemist, had been involved in developing selegiline as a drug for Parkinsons, in collaboration with Peter Reiderer. He wanted to find a similar compound that would have fewer side effects, and around 1977, at about the same time he moved from London to Haifa to join the faculty of Technion, he noticed that rasagiline could potentially be such a compound.[22] He called that compound, AGN 1135.[23]

In 1996 Youdim, in collaboration with scientists from Technion and the US National Institutes of Health, and using compounds developed with Teva Pharmaceutical, published a paper in which the authors wrote that they were inspired by the racemic nature of deprenyl and the greater activity of one of its steroisomers, L-deprenyl, which became selegiline, to explore the qualities of the isomers of the Aspro compound, and they found that the R-isomer had almost all the activity; this is the compound that became rasagiline.[23] They called the mesylate salt of the R-isomer TVP-1012 and the hydrochloride salt, TVP-101.[23]

Teva and Technion filed patent applications for this racemically pure compound, methods to make it, and methods to use it to treat Parkinsons and other disorders, and Technion eventually assigned its rights to Teva.[24]

Moussa B.H. Youdim identified it as a potential drug for Parkinson's disease, and working with collaborators at Technion – Israel Institute of Technology in Israel and the drug company, Teva Pharmaceutical, identified the R-isomer as the active form of the drug.[25]

Teva began development of rasagiline, and by 1999 was in Phase III trials, and entered into a partnership with Lundbeck in which Lundbeck agreed to share the costs and obtained the joint right to market the drug in Europe.[26] In 2003 Teva partnered with Eisai, giving Eisai the right to jointly market the drug for Parkinson's in the US, and to co-develop and co-market the drug for Alzheimers and other neurological diseases.[27]

It was approved by the European Medicines Agency for Parkinson's in 2005[17] and in the US in 2006.[20]: 255

Research

Rasagiline was tested for efficacy in people with multiple system atrophy in a large randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind disease-modification trial; the drug failed.[28]

Teva conducted clinical trials attempting to prove that rasagiline did not just treat symptoms, but was a disease-modifying drug - that it actually prevented the death of the dopaminergic neurons that characterize Parkinson's disease and slowed disease progression. They conducted two clinical trials, called TEMPO and ADAGIO, to try to prove this. The FDA advisory committee rejected their claim in 2011, saying that the clinical trial results did not prove that rasagiline was neuroprotective. The main reason was that in one of the trials, the lower dose was effective at slowing progression, but the higher dose was not, and this made no sense in light of standard dose-response pharmacology.[29][30]

See also

References

- ↑ Akao Y, Maruyama W, Yi H, Shamoto-Nagai M, Youdim MB, Naoi M (June 2002). "An anti-Parkinson's disease drug, N-propargyl-1(R)-aminoindan (rasagiline), enhances expression of anti-apoptotic bcl-2 in human dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells". Neuroscience Letters. 326 (2): 105–8. doi:10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00332-4. PMID 12057839. S2CID 29736753.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Rasagiline Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "DailyMed - RASAGILINE MESYLATE tablet". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 446. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ "Rasagiline (Azilect) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ↑ "Azilect". Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ↑ Stolberg, Victor B. (27 October 2017). ADHD Medications: History, Science, and Issues. ABC-CLIO. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-61069-726-2. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Stocchi F, Fossati C, Torti M (2015). "Rasagiline for the treatment of Parkinson's disease: an update". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 16 (14): 2231–41. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1086748. PMID 26364897. S2CID 6823552.

- ↑ Poewe W, Mahlknecht P, Krismer F (September 2015). "Therapeutic advances in multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy". Movement Disorders. 30 (11): 1528–38. doi:10.1002/mds.26334. PMID 26227071. S2CID 30312372.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9 Azilect Prescribing Information Archived 2021-04-06 at the Wayback Machine Label last revised May, 2014

- ↑ "Rasagiline Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ↑ Engberg G, Elebring T, Nissbrandt H (November 1991). "Deprenyl (selegiline), a selective MAO-B inhibitor with active metabolites; effects on locomotor activity, dopaminergic neurotransmission and firing rate of nigral dopamine neurons". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 259 (2): 841–7. PMID 1658311.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lemke TL, Williams DA, eds. (2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 434. ISBN 978-1609133450.

- ↑ Bar Am O, Amit T, Youdim MB (January 2004). "Contrasting neuroprotective and neurotoxic actions of respective metabolites of anti-Parkinson drugs rasagiline and selegiline". Neuroscience Letters. 355 (3): 169–72. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.067. PMID 14732458. S2CID 20471004.

- ↑ Yasar S, Goldberg JP, Goldberg SR (1996-01-01). "Are metabolites of l-deprenyl (selegiline) useful or harmful? Indications from preclinical research". Journal of Neural Transmission. Supplementum. 48: 61–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-7494-4_6. ISBN 978-3-211-82891-5. PMID 8988462.

- ↑ Chen JJ, Swope DM (August 2005). "Clinical pharmacology of rasagiline: a novel, second-generation propargylamine for the treatment of Parkinson disease". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 45 (8): 878–94. doi:10.1177/0091270005277935. PMID 16027398. S2CID 24350277. Archived from the original on 2012-07-11. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Schapira A, Bate G, Kirkpatrick P (August 2005). "Rasagiline". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 4 (8): 625–6. doi:10.1038/nrd1803. PMID 16106586.

- ↑ Binda C, Hubálek F, Li M, Herzig Y, Sterling J, Edmondson DE, Mattevi A (December 2005). "Binding of rasagiline-related inhibitors to human monoamine oxidases: a kinetic and crystallographic analysis". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 48 (26): 8148–54. doi:10.1021/jm0506266. PMC 2519603. PMID 16366596.

- ↑ Lecht S, Haroutiunian S, Hoffman A, Lazarovici P (June 2007). "Rasagiline - a novel MAO B inhibitor in Parkinson's disease therapy". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 3 (3): 467–74. PMC 2386362. PMID 18488080.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Richard B. Silverman, Mark W. Holladay. The Organic Chemistry of Drug Design and Drug Action, 3rd Edition. Academic Press, 2014 ISBN 9780123820310

- ↑ US 3,513,244 Archived 2021-04-28 at the Wayback Machine. See US patent 5453446 Archived 2021-04-28 at the Wayback Machine, lines 50-60. US Patent 5453446 was the patent at issue in Teva v Watson Archived 2016-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, see page 2

- ↑ Sielg-Itzkovich J (13 November 2010). "Making armor for the brain". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Finberg JP, Lamensdorf I, Commissiong JW, Youdim MB (1996). "Pharmacology and neuroprotective properties of rasagiline". Journal of Neural Transmission. Supplementum. 48: 95–101. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-7494-4_9. PMID 8988465.

- ↑ Teva v Watson Archived 2016-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, see page 2

- ↑ Lakhan SE (July 2007). "From a Parkinson's disease expert: Rasagiline and the future of therapy" (PDF). Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-2-13. PMC 1929084. PMID 17617893. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2021-04-07.

- ↑ Kupsch A (May 2002). "Rasagiline. Teva Pharmaceutical". Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 3 (5): 794–7. PMID 12090555.

- ↑ Eisai Press Release Archived 2014-09-16 at the Wayback Machine. May 15, 2003

- ↑ Poewe W, Mahlknecht P, Krismer F (September 2015). "Therapeutic advances in multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy". Movement Disorders. 30 (11): 1528–38. doi:10.1002/mds.26334. PMID 26227071. S2CID 30312372.

- ↑ Sviderski V (19 October 2011). "FDA Advisers Refuse Teva Plea to Expand Azilect Label". Reuters and Haaretz. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ↑ Katz R, et al. "Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee Background Package on Azilect" (PDF). FDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- "Rasagiline mesylate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-10-26. Retrieved 2021-04-07.

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: date format

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2013

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Chemicals using indexlabels

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drug has EMA link

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Articles with changed CASNo identifier

- Articles with changed KEGG identifier

- Nootropics

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

- Antiparkinsonian agents

- Indanes

- Alkyne derivatives

- Orphan drugs

- RTT